Blocking Reform

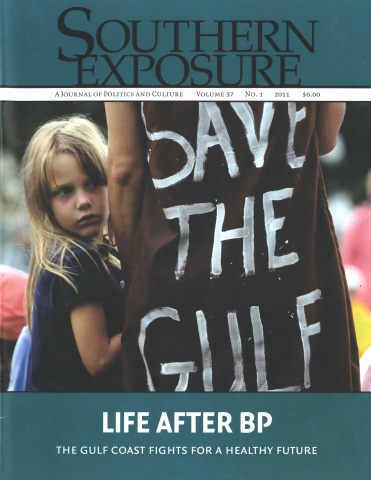

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 37 No. 1, "Life After BP." Find more from that issue here.

In May 2010, with oil still gushing from BP’s failed Deepwater Horizon rig in the Gulf of Mexico and inundating the coast with pollution, the Obama administration took what, at the time, seemed like a tepid step: The Department of Interior announced a six-month freeze on new deepwater oil drilling.

The temporary moratorium affected only some 30 future projects; not a single oil-producing well in the Gulf was stopped. But that didn’t stop Louisiana politicians and energy interests from declaring it an act of war on Gulf states—and swiftly joining forces to fight back.

Edison Chouest Offshore, the nation’s largest drilling services company and led by billionaire Republican donor Gary Chouest, warned that the moratorium would immediately lead to “mass layoffs” and over $300 million in losses. Louisiana Gov. Bobby Jindal followed by declaring—at an “Economic Survival Rally” organized by energy companies including Edison Chouest—that the drilling pause was a “second disaster” for the Gulf Coast on par with the BP spill itself.

Dire warnings of lost jobs and economic calamity soon flowed from every corner of Louisiana. In a ruling that temporarily struck down the moratorium, a federal district judge in New Orleans—who himself held significant energy investments—claimed that the president’s decision could eliminate up to “150,000 jobs” and cause “irreparable harm” to the Gulf economy. A Louisiana State University economics professor, with funding from the oil industry-backed American Energy Alliance, claimed the federal government’s measure would cause $2.1 billion in losses over time.

Sen. Mary Landrieu (D-Louisiana) even went so far as to block Obama’s nomination for the Office of Management and Budget to protest the moratorium’s “detrimental impacts” on the Gulf region.

But while the environmental health hazards of BP’s drilling disaster unfolded, the feared economic collapse never materialized. As of August 2010, only two exploratory rigs had left Gulf waters, as the New Orleans Times-Picayune reported. By October 2010, the region had churned out 502 million barrels of oil, putting it on track to match the 569 million barrels pumped in 2009—and far exceed the 422 million from 2008.

And what about the thousands of lost jobs? The state’s own economic numbers showed few displaced by the moratorium. The Louisiana Workforce Commission—despite having sent a representative to another industry-sponsored rally in July 2010 to warn of widespread job losses—issued rosy reports of record job gains throughout 2010, ending with a December press release that proudly announced Louisiana employment was at its “highest level since April 2009.”

“Having job gains for six straight months is a welcome growth trend,” enthused Curt Eysink, the commission’s executive director in the end-of-year report. “Many other states would like to see this type of growth.”

But the relentless attacks on President Obama’s drilling policy resulted in a big political victory for the energy industry: By early April 2011, the administration had approved nine permits for new deepwater projects in the Gulf of Mexico—even though Congress, in the words of the Times-Picayune, had done “virtually nothing” to address the regulatory failures raised by the BP disaster.

Oiling the Political Machine

The moratorium jobs scare was a classic case study of the Gulf Coast energy lobby in action—a powerful network of people, companies and groups that for decades have used their economic and political clout to ensure lawmakers look out for their interests, and stave off rules and regulations addressing the health and environmental consequences of the energy industry’s activities.

As the moratorium jobs debate revealed, in many cases the economic clout of the Gulf energy industry speaks for itself: Merely raising the specter of job losses and reduced investment is often enough to win public and political support.

But when flexing their economic muscle isn’t enough, oil and gas companies also know how to navigate the halls of government through one of the most powerful and sophisticated political pressure networks in the country.

First in the Gulf energy industry’s arsenal of political influence is spending millions of dollars in campaign contributions targeted at state and federal lawmakers. According to the Center for Responsive Politics, people and committees tied to oil and gas companies donated $238.7 million to candidates and parties between 1990 and 2010, one of the largest amounts of any industry.

More than 75 percent of those contributions have gone to Republicans.

Of the oil and gas contributions flowing to federal candidates, many are linked to companies with big investments in Gulf Coast oil drilling.

The “oil majors” like Conoco, Exxon and Shell are well-represented in the Gulf energy lobby, but many are like Edison Chouest Offshore—hardly national household names, but well-known among Louisiana politicians. In the 2009-2010 election cycle alone, members of the Louisiana congressional delegation received more than $156,000 in campaign contributions linked to Edison Chouest, making the company among the top 10 sources of contributions for all but two of the state’s eight U.S. senators and representatives.

Chouest is also a leading source of money in Louisiana state politics, where—as with federal contributions—the spending heavily favors Republicans. In 2008, the Chouest family and businesses donated more than $132,000 to Republican Gov. Bobby Jindal’s election campaign and local Republicans. Once in office, Jindal’s first economic development project steered $14 million in state incentives to expand a port in Terrebonne Parish that would boost Chouest’s plans for a shipbuilding facility, as the Baton Rouge Advocate reported.

The Louisiana company’s giving mirrors a pattern found across the Gulf Coast states. An analysis by the National Institute on Money in State Politics last year found that oil and gas interests pumped more than $21 million into state-level races between 2003 and 2008. That figure doesn’t even include money from petroleum refiners and marketers, a big part of the Louisiana energy industry.

That analysis also found that, during that five-year period, 89 percent of the money flowing directly to Gulf state partisan races benefited Republicans.

An Army of Lobbyists

For Gulf energy interests, equally important to achieving their political objectives is an army of lobbyists to pressure lawmakers.

At the state level, oil and gas companies have maintained a steady presence to curry favor among lawmakers. Between 2006 and 2008, 627 lobbyists representing oil and gas interests walked the halls of state government in five Gulf Coast states, according to the National Institute on Money in State Politics.

In Washington, oil and gas lobbyists—while never under-represented—have dramatically turned up their lobbying pressure in the face of Congressional debate over climate change and oil drilling. Between 2007 and 2009, the amount the industry spent on lobbying federal lawmakers more than doubled, from about $80 million to nearly $180 million, according to the Center for Responsive Politics’ OpenSecrets.org database.

Even the election of business-friendly Republican leadership in the U.S. House in 2010 hasn’t significantly dampened the industry’s investment: A Southern Exposure analysis of lobbying data finds that 15 of the biggest energy companies with leases in the Gulf of Mexico spent more than $22 million on federal lobbying in the first quarter of 2011 alone.

BP, which spent just over $7 million on federal lobbying in 2010, spent more than $2 million in the first three months of 2011, according to reports the company filed with Congress.

The effectiveness of this lobbying apparatus was revealed in the controversy over use of chemical dispersants in the Gulf oil cleanup. Two kinds of dispersant manufactured by Nalco, a Naperville, Ill-based chemical company, were used in unprecedented levels, despite concerns about their toxicity and the availability of safer alternatives.

Nalco has a close relationship with the oil companies whose spills its product is designed to help clean up: Its board and executives include a BP board member and a top Exxon executive, and Nalco has also been involved in a joint business venture with Exxon.

At the time Nalco was trying to push adoption of its dispersant, it was also stepping up its lobbying in Congress. While the company spent just $90,000 on federal lobbying in 2009, that amount jumped to $440,000 in 2010, according to OpenSecrets.org.

Nalco recruited some heavy hitters to support its agenda on Capitol Hill. It hired as its in-house lobbyist Ramola Musante, a former official at the Environmental Protection Agency and Department of Energy. It also hired Ogilvy Government Relations, a prominent bipartisan lobbying firm whose other clients include the American Petroleum Institute and oil giant Chevron.

Among the Ogilvy lobbyists who worked for Nalco in 2010 were Drew Maloney, an administrative assistant to former Republican House Majority Whip Tom DeLay (R-Texas), and Joe Lapia, a former Senate aide to now-Vice President Joe Biden (D) and Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid (D-Nev.).

One of the pieces of legislation that Nalco lobbied on was the Safe Dispersants Act, a bill requiring advanced testing of dispersants to better understand their long-term effects on human health. The measure went nowhere in either the House or Senate.

Today Nalco’s efforts appear to be paying off: In April 2011, the company reported first-quarter 2011 profits of $117.4 million—up 465 percent from $25.2 million in the first quarter of 2010.

Channeling Industry Firepower

While the sums of money Gulf energy interests spend on campaign contributions and lobbying are daunting, they offer only a glimpse of the full clout of oil and gas interests, whose influence seeps into every corner of Gulf politics.

In 2003, for example, even the EPA under President George W. Bush—criticized by many as being too lenient on energy companies—threatened to strip Louisiana’s Department of Environmental Quality of its enforcement powers because it was succumbing to industry pressure and failing to punish companies that polluted the state’s air, rivers and streams.

“Our problem in Louisiana is we’ve had too many politicians cozy with the big oil companies, without a doubt,” Foster Campbell, the public service commissioner from North Louisiana, told National Public Radio. “Too many duck hunting trips, too many campaign contributions, too many steaks at Chris’ Steakhouse.”

Over the last year, oil interests have channeled much of this political firepower towards blocking federal action in the wake of the BP oil disaster—an effort that has been largely successful.

For example, one of the major issues raised by the Gulf disaster was the amount of financial liability that companies are responsible for in the wake of a spill. The Oil Pollution Act of 1990 set a cap of $75 million that “responsible parties” need to pay for cleanup costs and damages. Critics say the low figure—which doesn’t account for inflation—creates an incentive for spills.

After the BP spill resulted in billions of dollars in damages, many called for reform. As the federal government’s oil spill commission wrote:

The current $75 million cap on liability for offshore facility accidents is totally inadequate and places the economic risk on the backs of the victims and the taxpayers. The cap should be raised significantly to place the burden of catastrophic failure on those who will gain the economic rewards, and to compensate innocent victims.

But since May 2010, BP and other oil companies lobbying in Washington have successfully fended off any changes in the law. A measure to raise the cap shortly after the spill was blocked by Congressional Republicans; this spring, Republicans joined with Gulf Democrats like Sen. Mary Landrieu to weaken support for change.

“Time to Enter the 21 St Century”

In Washington, raising the oil spill liability cap was thought to be one of the easiest post-BP reforms to pass. The proposal’s failure makes advocates despair of tackling bigger challenges, like the dozens of exemptions oil and gas companies receive from environmental and safety laws.

For example, in 1976 Congress passed the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA), a landmark piece of legislation promising “cradle to grave” management of wastes, including those released during oil spills.

The law included a special Section C aimed at stringent regulation of any wastes that were deemed hazardous, using the following definition:

[A] solid waste, or combination of solid wastes, which because of its quantity, concentration, or physical, chemical or infectious characteristic may (A) cause, or significantly contribute to an increase in mortality or in increase in serious irreversible, or incapacitating reversible, illness; or (B) pose a substantial present or potential hazard to human health or the environment when improperly treated, stored, transported, or disposed of, or otherwise managed.

However, in 1980—after pressure from energy interests—Congress exempted oil field wastes until EPA could prove they posed a danger to human health and the environment. In 1988, the EPA under Ronald Reagan ultimately concluded oil wastes posed no such risk due to “adequate” state and federal regulations—a decision one EPA staffer later allowed was made for “entirely political reasons.”

In 2003, the Bush EPA re-affirmed and clarified the exemption. But health and environmental advocates say the BP disaster—and the health hazards it created for Gulf residents—offers a perfect opportunity to revisit the law.

Last September, the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) petitioned EPA Administrator Lisa Jackson, asking the agency to reconsider its exemption of wastes from oil, gas and geothermal energy. It pointed out that wastes from these industries had nearly doubled since the exemption took effect—and that evidence of health hazards had grown:

This request is based on overwhelming evidence that waste from the exploration, development and production of oil and natural gas is hazardous, taking into account its toxicity, corrosivity and ignitability, that it is released into the environment where it can cause harm, that state regulations are inadequate, and that there are numerous methods available to manage it as hazardous waste.

“The industry has expanded dramatically since 1988, meaning there is a lot more of this toxic waste that is not sufficiently regulated than there used to be,” said Amy Mall of the NRDC. “It’s time for the oil and gas industry to enter the 21st century and clean up its toxic mess.”

When energy lobbyists caught wind of NRDC’s proposal, they quickly sprang to action.

“[The petition] is consistent with NRDC’s pattern of opposing the development of American oil and natural gas in every possible venue,” claimed lobbyists for the Independent Petroleum Association of America in their Sept. 24, 2010 Washington Report newsletter. “IPAA is uniquely positioned to oppose the NRDC effort and will be initiating a thorough response.”

They had a point: As the newsletter notes, Lee Fuller—the IPAA’s vice president of government relations—was the Congressional staffer who wrote the original law that exempted oil companies from tougher hazardous waste regulation, 30 years before the BP disaster.

Tags

Chris Kromm

Chris Kromm is executive director of the Institute for Southern Studies and publisher of the Institute's online magazine, Facing South.

Sue Sturgis

Sue is the former editorial director of Facing South and the Institute for Southern Studies.