Disaster-stricken West Virginia coal mine has a history of trouble

In the worst disaster to strike the U.S. coal mining industry in a quarter-century, 25 miners have been confirmed dead so far from an explosion that occurred yesterday afternoon at the Upper Big Branch Mine in Raleigh County, W.Va., about 30 miles south of the state capital of Charleston.

Four miners remain missing, but rescue efforts were called off earlier today due to poor conditions inside the underground mine, where it's believed a spark from a rail car used to transport workers may have ignited a build-up of methane gas. Rescue teams are now drilling holes in an effort to try to get more oxygen inside.

The mine -- operated by Performance Coal Co., a subsidiary of Richmond, Va.-based Massey Energy, the largest coal producer in Central Appalachia -- has a history of problems since it began operations in 1994.

They include the previous deaths of three workers. In 1998, a contractor was killed at the mine when a support beam collapsed. In 2001, a miner died after a portion of the roof fell on him, and an electrician was electrocuted while repairing a shuttle car in 2003.

In addition, 177 miners and 52 contractors have suffered injuries at Upper Big Branch, according to data from the U.S. Mine Safety and Health Administration.

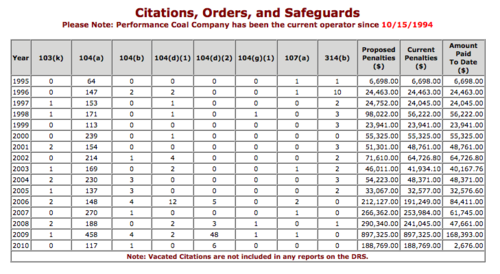

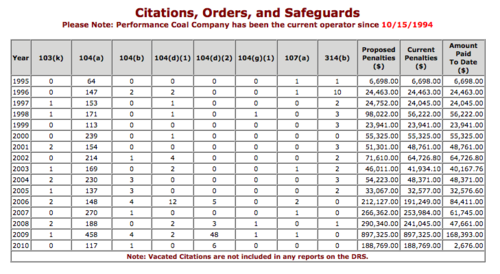

The facility, which employs about 200 non-union miners, has also faced numerous regulatory citations and orders over the years -- 3,011 through 2009, with a peak of 515 last year alone. So far this year, the mine has already racked up 124 citations and orders, as shown in these tables from the MSHA website (click on image to see a larger version):

Massey has a history of serious problems at other mines as well. In 2008 the company's Aracoma Coal subsidiary pleaded guilty to 10 criminal charges including a felony count in connection with a 2006 fire at a mine in Logan County, W.Va. that killed two miners. The company admitted to failing to provide a proper escape tunnel, not conducting required evacuation drills and falsifying a record book so it appeared the drills had been done.

Massey has a history of serious problems at other mines as well. In 2008 the company's Aracoma Coal subsidiary pleaded guilty to 10 criminal charges including a felony count in connection with a 2006 fire at a mine in Logan County, W.Va. that killed two miners. The company admitted to failing to provide a proper escape tunnel, not conducting required evacuation drills and falsifying a record book so it appeared the drills had been done.

The possibility that a methane build-up was behind the Upper Big Branch explosion raises the specters of the 2006 disasters at the Sago and Darby mines in West Virginia and Kentucky, which killed 17 people. In response to those tragedies, regulators vowed to examine safety concerns in sealed areas of mines where the explosive gas can build up. Among the previous violations at Upper Big Branch was the failure to properly vent methane gas.

The area where the mine is located is represented in Congress by Rep. Nick Rahall, a Democrat. He has promised a thorough investigation into what caused the disaster.

"We will look for inadequacies in the law and enforcement practices, and I will work to fix any we find," he said. "We will scrutinize the health and safety violations at this mine to see whether the law was circumvented and miners precious lives were willfully put at risk, and there will be accountability."

U.S. Labor Secretary Hilda Solis also pledged to take action. "Twenty-five hardworking men died needlessly in a mine yesterday. I pledge that their deaths will not be in vain," she said. "The federal Mine Safety and Health Administration will investigate this tragedy, and take action. Miners should never have to sacrifice their lives for their livelihood."

The Upper Big Branch disaster is the deadliest accident in a U.S. mine since December 1984, when 27 workers were killed in a fire at the Wilberg Mine in Orangeville, Utah.

The type of coal mining being done at Upper Big Branch is what's known as longwall mining, a highly productive method that uses enormous machines to extract coal quickly and cheaply. However, as documented in a Center for Public Integrity investigation, the method has significant social and environmental costs.

One of the four men still missing was thought to have been operating longwall mining equipment deep inside the mine, the Charleston Gazette reports.

Four miners remain missing, but rescue efforts were called off earlier today due to poor conditions inside the underground mine, where it's believed a spark from a rail car used to transport workers may have ignited a build-up of methane gas. Rescue teams are now drilling holes in an effort to try to get more oxygen inside.

The mine -- operated by Performance Coal Co., a subsidiary of Richmond, Va.-based Massey Energy, the largest coal producer in Central Appalachia -- has a history of problems since it began operations in 1994.

They include the previous deaths of three workers. In 1998, a contractor was killed at the mine when a support beam collapsed. In 2001, a miner died after a portion of the roof fell on him, and an electrician was electrocuted while repairing a shuttle car in 2003.

In addition, 177 miners and 52 contractors have suffered injuries at Upper Big Branch, according to data from the U.S. Mine Safety and Health Administration.

The facility, which employs about 200 non-union miners, has also faced numerous regulatory citations and orders over the years -- 3,011 through 2009, with a peak of 515 last year alone. So far this year, the mine has already racked up 124 citations and orders, as shown in these tables from the MSHA website (click on image to see a larger version):

Massey has a history of serious problems at other mines as well. In 2008 the company's Aracoma Coal subsidiary pleaded guilty to 10 criminal charges including a felony count in connection with a 2006 fire at a mine in Logan County, W.Va. that killed two miners. The company admitted to failing to provide a proper escape tunnel, not conducting required evacuation drills and falsifying a record book so it appeared the drills had been done.

Massey has a history of serious problems at other mines as well. In 2008 the company's Aracoma Coal subsidiary pleaded guilty to 10 criminal charges including a felony count in connection with a 2006 fire at a mine in Logan County, W.Va. that killed two miners. The company admitted to failing to provide a proper escape tunnel, not conducting required evacuation drills and falsifying a record book so it appeared the drills had been done.The possibility that a methane build-up was behind the Upper Big Branch explosion raises the specters of the 2006 disasters at the Sago and Darby mines in West Virginia and Kentucky, which killed 17 people. In response to those tragedies, regulators vowed to examine safety concerns in sealed areas of mines where the explosive gas can build up. Among the previous violations at Upper Big Branch was the failure to properly vent methane gas.

The area where the mine is located is represented in Congress by Rep. Nick Rahall, a Democrat. He has promised a thorough investigation into what caused the disaster.

"We will look for inadequacies in the law and enforcement practices, and I will work to fix any we find," he said. "We will scrutinize the health and safety violations at this mine to see whether the law was circumvented and miners precious lives were willfully put at risk, and there will be accountability."

U.S. Labor Secretary Hilda Solis also pledged to take action. "Twenty-five hardworking men died needlessly in a mine yesterday. I pledge that their deaths will not be in vain," she said. "The federal Mine Safety and Health Administration will investigate this tragedy, and take action. Miners should never have to sacrifice their lives for their livelihood."

The Upper Big Branch disaster is the deadliest accident in a U.S. mine since December 1984, when 27 workers were killed in a fire at the Wilberg Mine in Orangeville, Utah.

The type of coal mining being done at Upper Big Branch is what's known as longwall mining, a highly productive method that uses enormous machines to extract coal quickly and cheaply. However, as documented in a Center for Public Integrity investigation, the method has significant social and environmental costs.

One of the four men still missing was thought to have been operating longwall mining equipment deep inside the mine, the Charleston Gazette reports.

Tags

Sue Sturgis

Sue is the former editorial director of Facing South and the Institute for Southern Studies.