This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 36 No. 3/4, "A New Day for the South?" Find more from that issue here.

“Let New Orleans be the place inhere we strengthen those bonds of trust, where a city rises up on a new foundation that can be broken by no storm. Let New Orleans become the example of what America can do when we come together, not a symbol for what we couldn’t do.” — Barack Obama campaign speech in New Orleans, Aug. 26, 2007

More than three years after hurricanes Katrina and Rita devastated the U.S. Gulf Coast, the ongoing disaster in the region appears to have vanished from the Bush administration’s radar — at the very time the region is struggling with fresh destruction from a new round of deadly storms in 2008.

Indeed, the last pronouncement from the White House about the Gulf Coast came on Aug. 31, when President Bush announced he was forgoing the Republican National Convention to visit evacuees of Hurricane Gustav, the Category 2 storm that made landfall on the Louisiana coast, causing $4 billion in damage and killing 43 people in the U.S.

Less than two weeks later, Hurricane Ike — another Cat 2 storm — came ashore at Galveston, Texas, killing 82 people and racking up $27 billion in damage to become the third-costliest U.S. hurricane since Katrina in 2005 and Andrew in 1992.

With their communities’ needs over-shadowed by the 2008 elections, leaders across the Gulf expressed frustration over the lack of federal attention to Gustav and Ike’s devastation. A week before Thanksgiving, Texas Gov. Rick Perry (R) blasted what he called a “broken” federal recovery system for allowing displaced people to still be sleeping in cars and tents while mountains of storm debris — possibly containing human bodies — festered untouched. Local officials in Texas and Louisiana complained that FEMA was slow to reimburse them for storm-related expenses, pushing local governments to the brink of financial collapse.

But Gulf Coast recovery advocates see hope in the election of Barack Obama, who has long championed the region’s needs.

“It means a chance for a do-over,” says James Perry, executive director of Americans for Gulf Coast Recovery, a citizens’ lobby created in 2006. “Katrina fatigue had become the norm, but this new administration has said Gulf Coast reconstruction is a priority. We’re already getting calls from people close to the administration asking about what they need to go back and correct.”

The President’s Promises

Perry, an attorney who also directs the Greater New Orleans Fair Housing Action Center, argues that Obama and Congressional Democrats owe their 2008 electoral successes in part to the Bush administration’s mishandling of the Katrina crisis, which was a key political turning point.

“Before the disaster, it was difficult to criticize the Iraq War,” Perry says. “But when the storms happened, people started to question the administration. How can they handle a war if they can’t save New Orleans? This created an opening, and it’s part of why the Obama campaign had great respect for the region.”

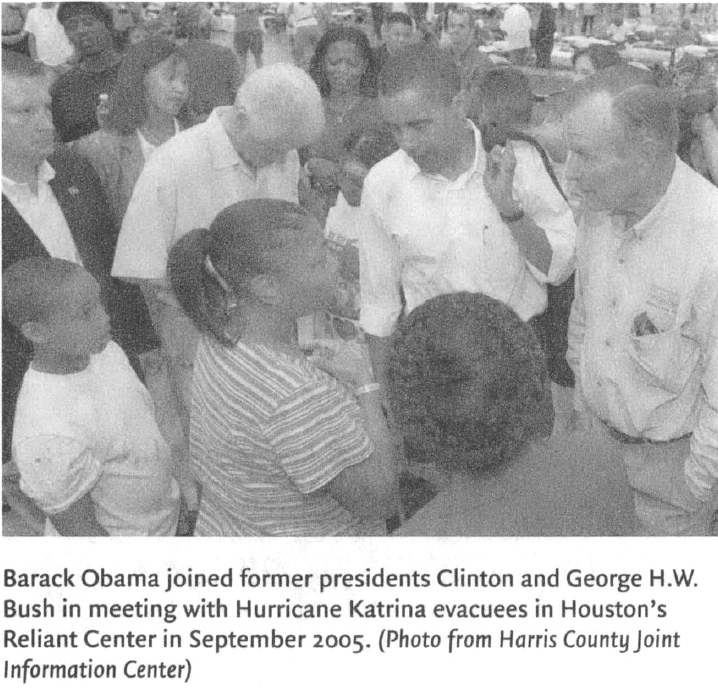

Perry and others point out that Obama’s concern for the Gulf Coast didn’t start only after he entered the presidential race. Days after Katrina blew ashore, the Senator from Illinois visited evacuees in Houston along with former Presidents Clinton and Bush — the first of Obama’s four official post-disaster trips to the region. Afterward, Obama blasted the “unconscionable ineptitude” of the government storm response:

“[W]hoever was in charge of planning and preparing for the worst case scenario appeared to assume that every American has ±e capacity to load up their family in an SUV, fill it up with $100 worth of gasoline, stick some bottled water in the trunk, and use a credit card to check in to a hotel on safe ground,” he said. “I see no evidence of active malice, but I see a continuation of passive indifference on the part of our government towards the least of these.”

Obama went on to introduce a number of Katrina-related proposals in the Senate. They included legislation to create a national emergency family locator system, launch an emergency volunteer corps, establish better oversight of recovery spending, speed tax refunds to Katrina victims, require evacuation plans to account for the most vulnerable, extend the Child Tax Credit to low-income parents in disaster-affected counties and end no-bid reconstruction contracts.

Obama also made the need for Gulf Coast rebuilding a key theme of his presidential campaign. He released a plan that included proposals to strengthen New Orleans’ levee and pumping systems, boost crime control, ensure federal reconstruction money reaches local communities, rebuild hospitals, and recruit doctors to the region. He also called for fixing FEMA by requiring the director to have professional emergency management experience, serve a fixed six-year term to insulate him or her from politics, and report directly to the President.

“The words ‘never again’ cannot be another empty phrase,” Obama said during an Aug. 26, 2007 campaign tour of New Orleans’ hard-hit Gentilly Woods neighborhood. “It cannot become another broken promise.”

A Stalled Recovery

Gulf Coast residents are hoping this is more than just political rhetoric as they grapple with a host of formidable obstacles to recovery.

One of the most daunting is a severe shortage of affordable housing. Skyrocketing rents — 46 percent higher in New Orleans today than before Katrina — have made it difficult for many storm-displaced families to find affordable housing. At the same time, government programs to help small landlords rebuild have proven ineffective.

A recent Associated Press investigation found that $850 million in federal aid meant for mom-and-pop landlords was stuck in bureaucratic red tape at Louisiana’s Small Rental Property Program, which is run by private contractor ICF International of Virginia — the same company whose troubled performance running the state’s Road Home rebuilding program for homeowners led state lawmakers to call for the cancellation of its contract. While the Small Rental Property Program promised to help as many as 13,000 small landlords, as of November 2008 it had made grants to only 352.*

The post-storm policies of the Bush administration have only exacerbated the situation. In New Orleans, for example, the Department of Housing and Urban Development allowed private developers to demolish almost 5,000 public housing units that sustained relatively little storm damage, with plans to replace them with mixed-income communities. HUD also allowed Mississippi Gov. Haley Barbour (R) to divert $570 million in federal funds meant for post-Katrina housing needs to expand the Port of Gulfport.

The 2008 storms further deepened the region’s housing crisis, flooding 12,000 homes in Louisiana alone, according to the Louisiana Recovery Authority. Many of those displaced by Gustav and Ike were still homeless two months later. And while FEMA is no longer distributing the temporary travel trailers that were found to be contaminated with dangerously high levels of health-damaging formaldehyde after Katrina, it still hasn’t come up with a functional alternative for providing temporary housing after disasters.

The region’s housing crisis isn’t confined to renters. Two of every three homeowners in Louisiana — and four of every five in New Orleans — assisted by the state’s Road Home program didn’t get enough money to cover needed repairs, with homeowners in historically African-American communities facing the largest shortfalls. In addition, many of those same African-American communities remain vulnerable to future disaster, with U.S. Army Corps of Engineers flood risk maps for New Orleans’ neighborhoods affected by the post-Katrina levee breaches showing a reduction in potential flood levels of 5.5 feet in predominantly white neighborhoods but only between 6 inches and 2 feet in predominantly black neighborhoods.

Serious public health problems created or exacerbated by the disasters are another barrier to recovery. These include tuberculosis among New Orleans’ increased homeless population, respiratory and other health problems caused by formaldehyde in FEMA trailers, and an epidemic of malnutrition-related anemia among children living in Louisiana’s largest FEMA trailer park.

At the same time, the region’s badly damaged medical infrastructure has been slow to rebuild, leaving many Gulf Coast residents without adequate health care — especially New Orleans’ African American residents, whose death rate jumped an estimated 50 percent in Katrina’s wake.

A NEW AGENDA for the GULF

Advocacy groups like Americans for Gulf Coast Recovery are gearing up to make their case to the new administration, drawing up a set of proposals to dismantle the biggest obstacles to rebuilding.

A new Gulf housing policy, Perry and others say, must start with the idea that affordable housing for those uprooted by the storms is a basic human right, as enshrined in the U.S.-approved United Nations Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement.

“There’s an obligation to make sure every person has the right to return, regardless of income,” Perry says.

While Obama’s Gulf Coast recovery plan mentions the general need to boost the region’s supply of rental property, Perry has some specific suggestions on how to do that. In addition to fixing Louisiana’s troubled Small Rental Property Program, he also calls for increasing available tax credits that require developers to set aside some reduced-rent apartments for families earning significantly less than the area’s median gross income.

Jobs are another priority for recovery advocates. In fact, many of them — including Americans for Gulf Coast Recovery — are part of the Gulf Coast Civic Works Campaign, a nonpartisan partnership of community, faith, student, labor and human rights organizations advocating federal legislation based on House Resolution 4048, the Gulf Coast Civic Works Act. This legislation would establish a regional authority to fund resident-led recovery projects, creating 100,000 good-paying jobs and training opportunities for local and displaced workers to rebuild infrastructure and restore the environment — a proposal similar to Obama’s plan to address the recession by making the largest investment in the nation’s infrastructure since the 1950s.

A New Deal-style public works program in the region would be a major departure from current policy, but momentum for the Gulf Coast Civic Works program has been growing since Obama’s election. On Nov. 14, 2008, students from 26 U.S. colleges gathered in New Orleans to draw up a campus action plan to help pass the act in the first 100 days of the Obama administration. Less than a week later, the New Orleans City Council endorsed the legislation. And in early December, the Center for American Progress — a leading liberal think tank from which Obama pulled many transition team members — requested that $1 billion for Gulf Coast Civic Works be included in the second economic stimulus package being considered by Congress.

Meanwhile, Americans for Gulf Coast Recovery has launched a petition drive reminding Obama of his campaign promises to help the Gulf rebuild. The petition calls on the federal government to give families a voice in the recovery process, ensure access to education, invest in small businesses, streamline the federal bureaucracy, repair wetlands and create long-term disaster recovery plans for every U.S. region.

“The key is to get our new leaders’ attention and to remind them of the need,” Perry says. “We have to start anew here.”

* “Rents up in New Orleans while $846m sits unclaimed,” by John Moreno Gonzales, The Associated Press, November 24, 2008.

Tags

Sue Sturgis

Sue is the former editorial director of Facing South and the Institute for Southern Studies.