This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 35 No. 1, "North Carolina at War." Find more from that issue here.

It was the summer of 2005, and North Carolina leaders were desperate. Over 200,000 jobs had vanished in the previous five years. Poverty was up and wages were flat; the state’s fund for unemployment benefits went bust twice in 2003 alone. The state’s cloudy economic forecast, combined with troubling news about the fate of North Carolina troops in Afghanistan and Iraq, were battering public livelihoods and morale, and state officials were scrambling for a quick boost.

Buried in a little-known outpost of the state’s community college system, researchers at the N.C. Military Business Center in Fayetteville thought they had the answer. They had just received a report from a firm called AngelouEconomics, arguing that the Bush administration’s ever-expanding “war on terror” shouldn’t be seen as a problem—it was a golden business opportunity.

“President Bush’s new strategic doctrine for the U.S. . . . signaled an end to the Cold War doctrine of deterrence because it failed to prevent terrorist attacks,” said the report, unassumingly titled Defense Industry Demand Analysis. “Instead, the administration outlined a doctrine based on preemptive action against rogue states believed to be harboring terrorists, most notably Al-Qaeda. . . . These changes place the U.S. on a permanent war footing.”

Being in a state of “permanent war” might not sound like a good thing, but AngelouEconomics was upbeat. The “staggering” growth of the U.S. defense budget—which has ballooned 41 percent since 2001, not counting $100 billion for the two wars—was making the military one of the nation’s top growth industries. By the Military Foundation’s estimation, if North Carolina increased its share of defense contracts by just .5% by 2010, the state would draw an additional $1.7 billion in Pentagon dollars and create 30,000 jobs.

A year and a half later, the Military Foundation may get their wish. Last December, Lt. Gov. Beverly Purdue announced the launch of the N.C. Military Foundation, a pioneering public-private collaboration aimed at dramatically boosting North Carolina’s take in the spoils of war.

NC Military Foundation Board of Directors

“The Foundation board is comprised of highly-decorated military leaders and the state’s top corporate citizens.”

—Office of the Lieutenant Governor, Bev Perdue

• Executive Director: Will Austin

• Chair. General Buck Kernan, USA, (Ret.)

• General Hugh Shelton, USA, (Ret.), former chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff

• General Jim Lindsay, USA (Ret.)

• Admiral Leighton Smith, USN, (Ret.)

• Lt. General Martin Berndt, USMC, (Ret.)

• Lt. General Buster Glosson, USAF, (Ret.)

• Lt. General Robert Springer, USAF, (Ret.)

• Ellen Ruff, President, Duke Energy Carolinas

• John Suttle, Sr. Director of Communications, General Dynamics Armament and Technical Products

• General Earnest Robbins, USAF, (Ret.) Senior Vice President, Parsons Corporation

• Fred Day, President and CEO, Progress Energy Carolinas

• David Parker, Executive Vice President and Regional President for Eastern North Carolina, Wachovia Bank

The 5 companies represented on the board gave $200,000 each in startup funds for the Military Foundation. The million dollars will reportedly pay Executive Director Will Austin’s salary, consulting fees, and costs of economic studies in the state.

Research by Jill Doub

“The North Carolina Military Foundation will help North Carolina become a national player in the defense industry business,” Purdue said in a statement. Noting that the state hasn’t landed many big defense contracts, she added: “This is the most military-friendly state in America and we can do better.”

Will the strategy work? Are there costs to becoming a bigger “player” in the military economy? Perdue declined to comment for this story, but the Foundation is gaining political steam and corporate backers, forcing the debate about who gains—and who loses—as North Carolina enmeshes itself deeper in a state of “permanent war.”

A Bigger Share of the Pie

North Carolina has earned its slogan of being “the most military-friendly state in America,” but mostly by serving as a home for bases, not a destination for defense dollars. State officials point out that North Carolina ranks third in number of active military personnel, but 25th for Defense Department prime contracts, according to DoD statistics.

Pentagon dollars haven’t bypassed the state entirely. In February, the Defense Department announced a $22.7 million contract to Asheboro-based Fox Apparel to make coats and trousers for the Army combat uniform. A week earlier, Raleigh-based Whiting-Turner Contracting Co. landed an $11.6 million contract to build a dining facility at Camp Lejeune near Jacksonville. And days earlier, Saft America received a contract of up to $30.9 million to make batteries for the Army, Navy, Air Force and Marines at its factory in Burke County.

But apparel, batteries and construction aren’t big-ticket items on the Defense Department’s rapidly growing shopping list. For instance, Michelin North America of Greenville, S.C. received a contract valued at $852 million on January 25 to supply, store and distribute tires for the four major branches of the military.

In addition, much of the contract money for construction at North Carolina’s sprawling military bases actually goes to companies located outside of the state. A $17.6 million contract awarded on January 22 to build an elementary school at Fort Bragg, home of the Army’s 82nd Airborne Division and Special Operations Command, went to RC Construction Co. of Greenwood, Miss.

“In North Carolina the emphasis has never been on high-tech industries,” said John Suttle, spokesman for General Dynamics Armament and Technical Products in Charlotte and a member of the new foundation’s board. “It’s economically tied to legacy industries such as textiles, furniture and agriculture. Only now is North Carolina able to present itself to defense contractors as an environment favorable to competitive operation in the globalized economy, and that is the case that the North Carolina Military Foundation is trying to make.”

Bev Perdue Campaign Contributors

Bev Perdue (D), elected Lieutenant Governor in 2000 and re-elected in 2004, has publicly stated that she will run for Governor in 2008

Political Action Committee Contributions of the 5 startup corporations to Bev Perdue’s Campaign Committees

Duke Energy

Duke Energy Corporation PAC—State

—$4,000 to Friends of Perdue in 2004

—$1,000 to Beverly Eaves Perdue Campaign in 2002

—$2,000 to Bev Perdue in 1999

Duke Energy Corporation PAC

—$1,000 to Bev Perdue for Governor in 2005

Wachovia

Wachovia Bank NA, NC Employees for Good Gov.

—$5,000 to Bev Perdue campaign in 2000

Wachovia Corporation NC Employees for Good Gov. Federal Fund III

—$4,000 to Bev Perdue committee in 2006

Wachovia NC Employees for Good Gov. Fund

—$4,000 to Bev Perdue campaign in 2004

—$8,000 to Friends of Perdue in 2004

—$2,000 to Bev Perdue campaign in 2003

—$3,000 to Bev Perdue campaign in 2000

—$2,000 to Bev Perdue campaign in 1999

Wachovia employees made individual contributions to Bev Perdue’s campaign in 2004 election cycle totaling $6,150

Progress Energy

Progress Energy Employees of the Carolinas PAC

—$2,000 to Bev Perdue campaign committee in 2006

—$4,000 to Friends of Perdue committee in 2006

—$2,000 to Friends of Perdue committee in 2003

—$ 1,000 to Bev Perdue campaign in 2000

General Dynamics and Parsons have not contributed to Perdue’s campaigns

Research by Jill Doub

General Dynamics is one of five companies that have committed $200,000 over the next two years to get the foundation off the ground. The company relocated its armament and technical products division to Charlotte in 2003, receiving $7.8 million in corporate incentives from state and local governments in the process.

Common Interests

The Foundation’s success in attracting backers like General Dynamics can be traced back to the interlocking web of interests among the political, business and military leaders involved. Founding corporate partners include Duke Energy, Progress Energy, Wachovia Bank, and Parsons Corp., represented on the foundation board by retired Gen. Earnest Robbins.

Capitalizing on the state’s large military base presence, the foundation has recruited more than half a dozen retired military leaders to serve on its board of directors.

“We have an extraordinary amount of talent here in the civilian community and the military community transitioning into retirement that we can take advantage of,” said Gen. James J. Lindsay, a board member from Vass, N.C. who commanded the 82nd Airborne Division and Special Operations before retiring in 1990. Lindsay, like other retired military leaders, acknowledged that he has worked as a private consultant since his retirement.

Board members who have parlayed their military experience into lucrative second careers in the private sector include the chairman, retired Gen. Buck Kernan, who serves as vice president for Virginia-based MPRI; and retired Gen. Hugh Shelton, a consultant for shipbuilding giant Northrop Grumman.

The state’s two major utilities, Duke Energy and Progress Energy, also have an interest in bringing more military contracting to the state, as well as spurring economic development, their representatives point out. Ellen Ruff, president of Duke Energy Carolinas, serves on the foundation’s board. “We try to attract and retain industries to the Carolinas that have the best growth potential for the future or are already here,” Duke Energy spokeswoman Paige Sheehan said. “Clearly when you’ve already got a military infrastructure in the Southeast we see there is benefit in supporting economic development that supports that infrastructure. That’s why we’re involved at such a high level with Ellen serving on the board.

“Duke Energy cannot be successful unless its customers are successful,” Sheehan added. “When industry is in the region, that fuels the economy. They’re certainly large energy users, so it is all interconnected as far as we’re concerned.”

Scott Dorney, executive director of the Military Business Center, said construction companies should be encouraged to bid on base support contracts—an opportunity heretofore overlooked. “It’s primarily because they’re fully engaged in other sectors,” he said. “We have a booming commercial market and a booming public market with universities and community colleges. We’re trying to change that based on the huge projection of new [military] spending.”

An Economic Boost?

Those who have studied the historical development of the South’s military economy since World War II suggest that state boosters’ efforts to shift more contracting to North Carolina might be easier said than done.

“What stood the Southern states so well in getting defense contracts and facilities was the power of their congressional representatives, which was in great measure a function of their seniority and where they were positioned in the Democratic Party,” said Gavin Wright, a professor of American economic history at Stanford University. “Most of these things are a product of the Cold War, how they were positioned in relation to [President] Lyndon B. Johnson.”

James C. Cobb, a history professor at the University of Georgia and author of the classic text The Selling of the South: The Southern Crusade for Industrial Development, 1936-1990, said the concentration of military bases in the South has spurred a demand for goods and services to support those bases, but contracts for weapons development and other activities that would stimulate capital investment and create high-paying jobs have typically gone elsewhere.

“It’s likely to follow the pattern of states outside of the South getting the most lucrative contracts,” he said. “Most of the systems are pretty specialized and tend to be something coming off the research board. That’s going to benefit states with a research and development infrastructure.”

Cobb expressed skepticism about whether the state’s congressional delegation could develop the clout to steer high-end weapons development and research contracts to North Carolina.

“It’s just a question of how much pork barrel can be tolerated in these contracts,” he said. “If it’s a case of something where there’s urgent need, it’s going to be harder to conceal the fat or the pork barrel. You can conceal a certain amount of inefficiency or illogic, but if you are looking at it without the political coloration, it makes sense to go with a place that has more of a track record in dealing with cutting-edge technology.”

Morally Suspect or “Routine Business”

Others point to a moral cost should North Carolina become more successful at steering defense contracts to local businesses.

“Making money off the machinery of taking life is not something we believe is in our best interest for economic development,” said Barbara Zelter, a program associate at the Raleigh-based N.C. Council of Churches, which represents 15 mostly mainline Christian denominations in the state. “We understand that people believe that the military-economic complex is normal and fine. We agree with [President] Dwight D. Eisenhower that it’s dangerous. Just because it can be an economic engine doesn’t mean it’s the best vision of a sustainable economy here or anywhere.”

“I’m not knocking Bev Perdue,” Zelter added. “She’s going by a certain kind of logic of ‘if there’s a pie, get a piece of the pie.’ But the church has to speak with a different voice.”

Top Recipients of Department of Defense Dollars in North Carolina

URS Corporation—Charlotte, N.C.

Engineering Services

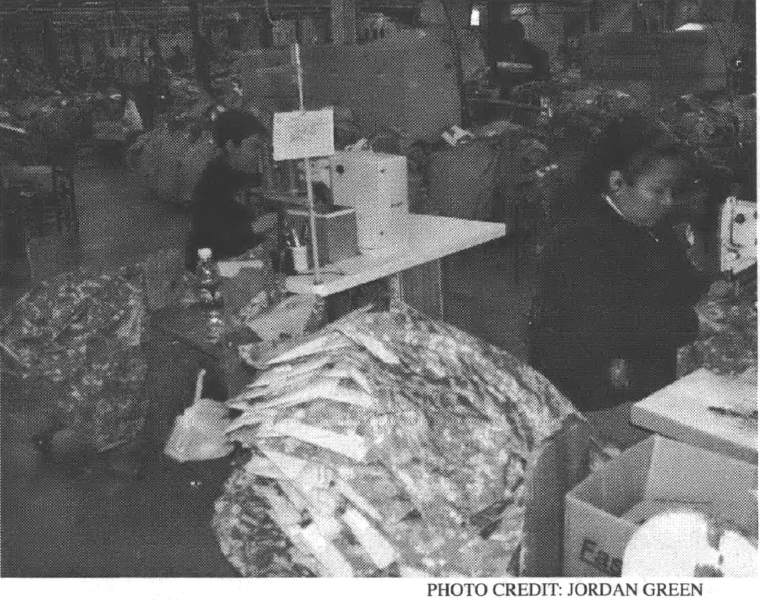

Saab Barracuda LLC—Lillington, N.C.

Camouflage and Decoys

General Dynamics Corporation, Charlotte, N.C.

Small Arms and Air Missiles

Blackwater USA, Moyock, N.C.

Security Services

Research by Kosta Harlan