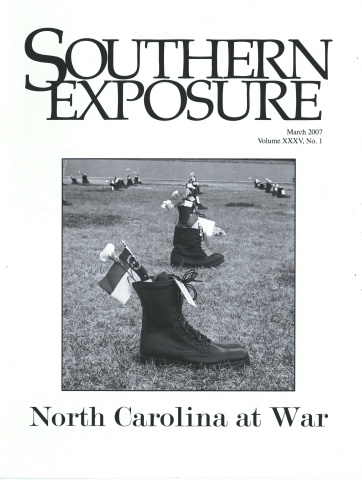

The Cost of War

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 35 No. 1, "North Carolina at War." Find more from that issue here.

Fort Bragg and Camp Lejeune. New River Air Station and Pope Air Force Base. The Blackwater USA training center. North Carolina is home to some of the nation’s largest and most significant military bases, where tens of thousands of active duty personnel—and countless more families, friends and communities—are directly or indirectly tied to the military and U.S. wars abroad.

In December 2006, Lt. Governor Beverly Perdue noted that “North Carolina has more active military personnel than all but two other states.” At a time when many states are slated for drastic cuts in military bases, the Pentagon’s latest plan recommends that North Carolina slightly grow, with a planned 4,145 decrease at Pope AFB more than balanced by a 4,325 boost at nearby Fort Bragg.

Along with North Carolina’s plans to lure more defense contracts to the state (see “A Player in the Business of War”), these trends indicate that the share of the state’s people and communities dependent on war will only grow. More base personnel and military contracts undoubtedly will offer the state a short-term economic boost.

But what are the costs of war to North Carolinians? War takes a toll in many ways, and it’s impossible to put a price tag on the loss of life and other social costs. North Carolina must face hard questions—how does this help our communities? what do we lose from war?—before seeking to expand its dependence on the military economy.

We All Pay for War

War spending—especially in the form of military bases and contracts—can offer a state like North Carolina an economic boost, but war has staggering economic costs as well.

The National Priorities Project, a non-profit budget watchdog, keeps a “Costs of War Calculator” to measure the cost of the Iraq war over time. By March 2007, NPP estimates, the United States will have accrued $378 billion in debt to finance the war. The “incremental costs” measured by NPP don’t include standard costs of military operations, like soldiers’ pay, but do include costs such as activating the National Guard, combat pay, equipping troops, paying for reconstruction, repairing and replacing equipment, and training Iraqi forces.

But even this measure doesn’t capture the full economic impact of war. “Potential future costs, such as future medical care for soldiers and veterans wounded in the war, are not included,” the researchers at NPP state. “It is also not clear whether the current funding will cover all military wear and tear. It also does not account for the Iraq War being deficit-financed and that taxpayers will need to make additional interest payments on the national debt due to those deficits.”

A similarly large estimate comes from Linda Bilmes, Assistant Secretary of Commerce in the Clinton Administration, and Joseph Stiglitz, a former chief economist at the World Bank and Nobel Prize recipient. They project the costs of the Iraq war alone will eclipse $2 trillion, an estimate that includes future costs of medical care for veterans, rebuilding the U.S. military, and interest payments on running up the debt to pay for the war.

Many of the costs of war balloon over time. In 2006, the Congressional Budget Office estimated that payments on debt used to finance the Iraq war will total between $264 and $308 billion dollars. Meeting the needs of veterans returning home from war will be even more costly to an already-overburdened Department of Veteran Affairs. “Government medical facilities are currently overwhelmed by the needs of soldiers injured in Iraq,” Bilmes and Siglitz write. “Some 144,000 of them sought care from the VA in the first quarter of 2006—23 percent more than the Bush administration had estimated for the entire year!”

Like all taxpayers, North Carolinians feel these costs in the end. Using their more conservative estimates of war costs, the National Priorities Project breaks down economic impact on a state-by-state basis, based on a state’s share of federal tax revenues. In their latest report, “The Local Costs of the Iraq War” (March 2007), the cost to North Carolina taxpayers alone is $12.3 billion.

Lost Lives, Devastated Communities

Misael Martinez, a 24-year-old soldier from Carrboro, N.C. was killed by a roadside bomb while on his third tour in Iraq in November 2006. According to a January 2007 article in The Independent Weekly, Martinez joined the army hoping to expand his options for college and a career. In January 2007, Israel Martinez, Misael’s younger brother, left for Iraq to serve his first tour of duty—two short months after burying his brother.

As of February 2007, 72 soldiers from North Carolina have died in Iraq, but some communities have borne more loss than others. According to a report released by the Associated Press in February 2007, almost half of the 3,100 U.S. military personnel killed in Iraq were from towns of less than 25,000 people.

Martin Luther King, Jr. once said that “war is an enemy of the poor,” and those of lower socio-economic status have paid more dearly in Iraq. Nearly three quarters of those military fatalities hailed from towns where the per capita income was below the national average.

The impact of each fallen soldier’s death can’t be measured in dollars and cents—it’s a devastating blow that ripples throughout the community. But there’s also a cost in cold economics: as Bilmes and Siglitz note, one of the long-term consequences is “the loss of productive capacity of the young Americans killed or seriously wounded in Iraq.”

Across the country, communities are struggling to care for veterans who return with debilitating injuries. The Washington Post recently exposed a host of scandals at Walter Reed Military Hospital, depicting infested, unsanitary conditions in its outpatient buildings and detailing stories of wounded veterans’ bureaucratic battles for promised assistance. These headlines are just the tip of the iceberg of an over-stretched system of long-term care for veterans.

According to Veteran Administration, the agency has a 400,000-case backup on new claims in the 2006 fiscal year. In an article from ArmyTimes.com, “Wounded and Waiting,” Col. Robert Norton, deputy director of Government Relations for the Military Officers Association of America, told the Committee on Veterans Affairs in 2006, “Taken together, the convalescence, [medical evaluation board] and [physical evaluation board] processes appear to average between nine and 15½ months for Army soldiers.” Recent reports from The Washington Times, Newsweek, and the LA Times are still discussing the VA’s disappointing response to soldiers’ needs.

A Marine s Story

Jacek Teller is a student at East Carolina University in Greenville, N.C. He’s uniquely qualified to talk about the costs of war—he was among the first U.S. Marines to enter Iraq in 2003.

Sergeant Teller joined the Marines for two reasons: he could no longer afford college, and he had always been driven to have an impact in the world. “When you join you feel like you are exploring your boyhood desires of doing something adventurous, rough and manly,” Teller said. “I decided to become a Marine because they used a different tactic from the Air Force or the Army—they told me that I wouldn’t make it. That was appealing.”

Teller joined the Marines in 1999 and was sent on his first six-month tour to Kuwait in 2001. He returned in 2003 to be a part of one of the initial flight missions into Iraq, whose job it was to secure oil refineries in Umm Qasr on the Faw Peninsula. The mission was extremely dangerous, Teller said, because they left at 3 a.m. in the middle of a sandstorm so terrible that there was no way of knowing the distance between their aircraft and the ground.

“One of our aircrafts took a nose dive and killed four American Marines and eight British Marines,” Teller said. “My best friend was one of the American Marines who died in that crash. That was a serious personal cost to me. There was no point in going on after he died. But you aren’t afforded grief when you are invading a country.” The mission that took his friend’s life was called off until the next day, after the oil fields were secured.

Teller and his company next moved north to Iraq’s cities, where they dropped off infantry troops to enter homes, separate the Iraqi men from women, and search houses for weapons. None of the soldiers spoke Arabic, and very few of the Iraqis spoke English.

“Troops with AK-47s were bursting into peoples’ homes and looking for weapons, and if the men misbehaved they were taken to prisons and holding facilities like Abu Ghraib,” Teller said. “Which is why there are roughly 14,000 arbitrary detainees in Iraq at any given time—then they wait for weeks or years to be interrogated. People at the processing facility are left with the problem of figuring out who was just yelling inside to their families and who is potentially harmful. I see that as another cost of this war—that Iraqi families have to endure this kind of trauma.”

Teller was in Iraq for a total of nine months. But he says the worst part was coming home.

“Nearly two years passed before it was clear to me that I was having emotional, psychological problems,” Teller said. “I felt abandoned. The Marines give you answers, they give you context—they look after you. After you are out, you begin realizing you were morally wrong. There is a lot of survivor’s guilt.”

Teller described feeling like he should be in prison and be punished for what he was a part of in Iraq. He spoke of soldiers who lost even more than he had.

“There is an extremely high divorce rate in the Marines. A lot of guys come back to empty homes,” Teller said. “It is hard to be worried every day about your loved ones and to know so little about what they are doing. Then when the soldiers do come home they don’t know how to react. There is no standard rehabilitation into society, no way to break away from the culture of violence to which you have become accustomed.”

Teller has found new ways to have impact. He joined Iraq Veterans Against the War, an organization with members in 41 states and many bases overseas. At a recent forum on the Iraq war, he drew on his experiences to spell out this warning: “Don’t buy into the drumbeat for war, don’t rally around the flag thinking it’s going to provide you security, because it’s not.”