Waste and Means

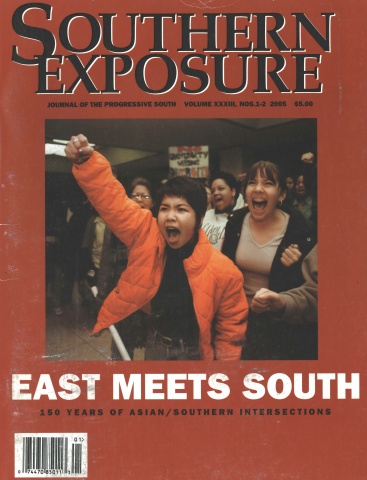

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 33 No. 1/2, "East Meets South." Find more from that issue here.

To the people who run the University of Alabama’s chemistry department in Tuscaloosa, Shelby Hall, named for Sen. Richard Shelby (R-Ala.), is worth every penny of the $60 million needed to build it. At more than 200,000 square feet, the recently opened building is “one of the most advanced research facilities in the country,” gushes the department’s web site, with “modern space for the teaching, research, and administrative functions of the department.”

To Brenda Haynie, any reckoning of the costs and benefits ought to include her son’s life. In January 2003, Matthew Haynie, a 29-year-old medical student, was driving from the family home in Fort Worth to Wake Forest University in North Carolina when his sport utility vehicle hydroplaned on Interstate-20 east of Birmingham, swooped backward across the median into the path of an 18-wheeler and burst into flames. Dental records were needed to identify his remains.

The dangers of that stretch of highway were so well-known that it bore the nickname “Death Valley.” Newspaper articles collected by Brenda Haynie show that local leaders had pleaded for median barriers and other safeguards. But while Shelby, chairman of a key Senate highway spending panel for more than six years, was steadily diverting millions of federal road dollars into construction of his namesake edifice, the perils of Death Valley an hour’s drive away went unaddressed.

“Shelby could sit there in good conscience and let people die,” Brenda Haynie says. “He didn’t give a damn.”

A spokeswoman for the senator responds that the Alabama Department of Transportation ultimately drives decisions on highway priorities. Wherever blame lies, the episode starkly illustrates the degree to which lawmakers nowadays are prone to grab the wheel when it comes to allocating federal dollars—and the complications that can follow.

Since the late 1990s, Shelby has steered nearly $150 million in highway funds to university science and engineering buildings named after him, as lawmakers cumulatively add billions every year for thousands of other politically chosen projects. In a recently released tally, Citizens Against Government Waste, a Washington, D.C. watchdog and advocacy organization, counted $27.3 billion in “pork” for fiscal 2005, a 19 percent jump over the preceding year.

Capitol Hill was supposed to work differently after Republicans took control of Congress a decade ago. Despite once ridiculing Democrats for porcine spending proclivities, however, “we came into office and we made it far worse,” Rep. Jeff Flake (R-Ariz.) lamented at a press conference announcing the new numbers.

Toting home the proverbial bacon is an especially honored tradition in the South, where the federal treasury has often compensated for the puniness of state and local tax bases. But if pork used to mean big-ticket public works endeavors like the Tennessee-Tombigbee Waterway, no cause or organization now seems too picayune for a handout.

Among the pressing national priorities singled out for taxpayer dollars in this year’s budget: the National Wild Turkey Federation in South Carolina, the Graveyard of the Atlantic Museum in North Carolina, and blackbird control in Louisiana.

Although Southern lawmakers are not unique, they may face more problems in reconciling lip service to government thrift with the practice of throwing federal money at local projects, says Keith Ashdown, vice president for policy at Taxpayers for Common Sense, another watchdog group in Washington.

“They’re kind of torn between two worlds: a philosophy of fiscal conservatism and the necessity to bring back as much federal dollars as possible to districts that don’t have a huge economic base.”

In defense of Shelby Hall, University of Alabama administrators say they had no other means for replacing the decrepit structure that housed the chemistry department. To justify the reliance on federal highway dollars for its construction, the new facility also hosts several transportation research programs.

In the lexicon of Capitol Hill, pork is more blandly known as “earmarking.” Broadly speaking, the label refers to an appropriation netted through political pull rather than merit competition or some other form of bureaucratic review.

Whatever the name, lawmakers stoutly uphold the practice on two grounds. First, that the Constitution gives Congress the power of the purse. Second, that they are better positioned than far-removed government drones to know constituents’ needs.

Although the $225,000 appropriation for the National Wild Turkey Federation has drawn national guffaws, for example, the organization’s development director, Donna Leggett, makes no apologies. The earmarked money will be spent on outreach to women, children and the disabled, she says, and makes up less than 10 percent of the federation’s overall spending on those programs.

They “are vital to preserving (our) outdoor heritage. That’s why we went to get more support.”

But lawmakers typically receive far more requests for help than they can fill. The process of apportioning the tenderloin is blanketed in near-total secrecy. Behind every earmark, “there’s a story,” says Ronald Utt, senior research fellow at the Heritage Foundation, a Washington, D.C. think tank, “and most of them are confidential.”

Sometimes, the plotline is as simple as following a name. This year’s budget contains $1 million for a runway extension at the Trent Lott International Airport in the Republican senator’s hometown of Pascagoula, Miss., and $6 million for various projects at the Robert C. Byrd National Technology Transfer Center, a Wheeling, West Virginia, facility named for the eight-term Democrat. Louisiana State University is in line for $300,000 to archive the papers of recently retired Sen. John Breaux, also a Democrat.

Then there’s the Country Music Hall of Fame in Nashville, which is up for $250,000. As it happens, the organization is also home to the Frist library, named for a foundation funded by the brother of Senate Majority Leader Bill Frist (R-Tenn.).

Nick Smith, a spokesman for the senator, acknowledged that Frist’s office was responsible for inserting the money, but said the staffers handling the paperwork knew nothing of the library and that Frist himself was not involved.

Asked why a private non-profit warrants government aid, Smith said the hall of fame “helps promote tourism and that provides growth for the Nashville community.”

By definition, however, earmarking is an act of favoritism. As the volume of earmarks skyrockets, securing them has turned into a roaring trade for lobbyists, often former staffers of the same lawmakers they are enlisting to help. To Utt and other critics, the result is the emergence of a de facto “pay to play” system. Directly appealing to your congressman for help is no longer enough. Increasingly, the perception is that a paid emissary is needed.

“We wanted to get in the loop of things,” says Rebecca Orr, director of member services for the Southern Highland Craft Guild in Asheville, N.C., in explaining why the 75-year-old cooperative turned to a Washington lobbying firm for help in getting federal money to upgrade and expand its Folk Art Center.

In that case, the experiment didn’t end happily. After spending about $45,000 on lobbying, the guild decided recently to simply work through the local congressman, says Thomas Bailey, the guild’s managing director.

“I don’t know what they do,” Bailey says of lobbyists.

Others continue to have faith. In North Carolina alone, about 20 local governments now have Washington representation, according to congressional records.

Among them is the City of Monroe, with a population of about 28,000, that last year spent $80,000 on lobbying for congressional help with airport and road needs.

“It just gave us a presence in Washington that we would not have had without a lobbyist,” says City Manager Douglas Spell, adding that he is satisfied with the firm’s performance thus far.

Considering that the name of the world’s most famous cyclist adorns its letterhead, one might think the Texas-based Lance Armstrong Foundation could make do without the taxpayer’s dime. In fact, the foundation is receiving $200,000 in earmarked money this year to expand cancer survivorship research centers in Philadelphia and Cleveland, spokeswoman Michelle Milford said via e-mail. In the first half of last year alone, congressional records show the foundation spent $80,000 on a lobby squad that included at least four former Hill staffers. The team represents the foundation “in a number of ways,” Milford said, besides helping to get earmarked funds.

At times, lawmakers may be helping themselves as well. Consider the cryptically named Simulated Prison Environment Crisis Aversion Tools, a high-tech training and modeling program for prison systems in North Carolina, Alabama, and Pennsylvania that has received almost $12 million since 2002. Although nowhere mentioned in the spending legislation, the lead contractor has been a Pennsylvania firm, Concurrent Technologies Corp., whose executives made $30,000 in campaign contributions in the last election cycle, mainly to members of the House and Senate appropriations committees, according to the Center for Responsive Politics. At least lately, Concurrent Technologies has also been using subcontractors in Alabama and Virginia; employees in those companies wrote checks for another $38,450. Last year, Justice Department auditors rapped federal managers for allowing Concurrent to hire the subcontractors without bids.

Overall, earmarks comprise a relatively small part of a federal budget that this year rings up to more than $2 trillion. But at a time of record federal deficits and a war-burdened military, some critics argue that any pork is too much, particularly when there is little accountability for how the money is actually allocated and spent.

“The subterranean aspects of the process reveal it to be a pretty foul process,” says Winslow Wheeler, a former congressional aide who charges lawmakers with squeezing defense training and readiness needs in favor of home-state pork.

Brenda Haynie bitterly concurs with that description. Too late for her son—although spurred perhaps by the publicity surrounding his death—concrete median barriers have since been added to Death Valley.

Still, though, she is waiting for an explanation from Shelby as to why he didn’t act.

So far, the only response has been a two-paragraph form letter, in which the senator thanked her for writing and said he was referring her inquiry to the state transportation department.

“Please do not hesitate to contact me,” he concluded, “about this or other matters in the future.”

Tags

Sean Reilly

Sean Reilly is the Washington correspondent for the Mobile Register. An earlier version of this piece appeared on the Facing South blog under the title “Swine Still Doing Fine” (2005)