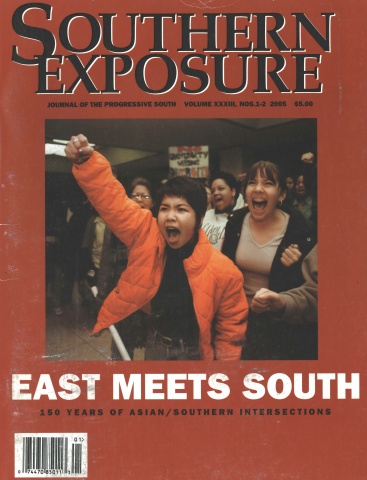

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 33 No. 1/2, "East Meets South." Find more from that issue here.

It is 5:30 in the morning on a misty dock along the coast of Galveston Bay. It’s the usual dawn for Chanh Le as he prepares his catch from the days before. He has been out at sea for several days and nights. His skin is dark and leathered and his eyes are glazed red, scorched from the blistering sun that burnishes the Texas Gulf. He looks especially weary, but he won’t rest just yet. He still has work to do. He piles the shrimp in heaps so his brother Minh, and two cousins, Ngan and Trinh, can sort them out by hand. Relying on more than twenty years of experience, they gauge the size of the shrimp with the naked eye. Grasping about a dozen in two hands, they remove the heads with a flick of all ten fingers. They do this until the last of the catch is sorted. There are no machines, no scales, no indications of technology whatsoever. The harvesting and sorting is all done by hand. This is the way of life for thousands of Vietnamese-American shrimpers.

Le, like the majority of Vietnamese-American shrimpers, arrived in the United States during the second and third waves of immigration following the end of the Vietnam War. Immigrants from the first wave arrived immediately after the fall of Saigon in April 1975 and up until around 1977. These refugees were mostly from the more privileged populations of Vietnam—mostly well-educated, relatively affluent, and often English-speaking. Many of them were also South Vietnamese soldiers or civilian workers for the U.S. military who fled Vietnam with American assistance.

The second and third wave refugees are commonly referred to as “boat people,” as they embarked on treacherous and often deadly journeys into the waters of the Gulf of Tonkin. Their hopes were to land in a country that would accept them for asylum, such as Malaysia or Thailand, and then possibly relocate to the U.S. or another western country. Second and subsequent wave immigrants were less educated and less advantaged than their predecessors. Many were from the rural parts of Vietnam, including shrimpers and fishermen from fishing villages like Nha Trang and Vung Tau.

A substantial majority of Vietnamese-American shrimpers came from Phuoc Tinh in Southern Vietnam. Many inhabitants of this fishing village were migrants from North Vietnam; opposed to communism, they were among the two million sojourners who trekked to South Vietnam following the 1954 Geneva Accord. After two decades of living and working free from the Communist government, the people of Phuoc Tinh panicked when Saigon fell to Northern troops in 1975. Nearly the whole village packed their boats and took to the open sea, hoping to make it to America.

After these refugees arrived in the U.S., their lack of formal education and unfamiliarity with English made it difficult for them to find work. But they had their fishery skills, so naturally they sought places of resettlement where they could put these abilities to use. Coastal towns along the Gulf of Mexico and eastern seaboard, with their warm weather and available work, seemed the best bets.

The initial good fortune of Vietnamese shrimpers in the South encouraged others to follow, and soon there was a substantial Vietnamese-American population along the coasts of Texas, Louisiana, Florida, and Mississippi, among other states. They prospered beyond what they could have imagined. In time, many owned multiple boats as well as retail and wholesale businesses. But along with their successes have come struggles. Through it all, many have managed to stay afloat in the shrimping industry, but this unique Asian-American community may be facing its most difficult challenges now, due to a “perfect storm” of environmental pressures, de facto racial discrimination, and a globalizing shrimp industry. It’s not at all clear whether it will survive.

In the 1970s and 80s, Vietnamese-American fishermen faced a mix of competitiveness and envy from disgruntled local shrimpers, mostly white, who had been long-time residents and workers in the area. The shrimp industry’s changing racial composition angered many white fishermen and shrimpers whose perceptions of these immigrants were shaped by racist portrayals of Vietnamese people during the U.S. war in Vietnam. Saigon had only recently fallen, and with over 58,000 American soldiers dead at the hands of the North Vietnamese and Viet Cong, negative images and stereotypes of Vietnamese people were transferred to the newly-arrived shrimpers. War-related prejudices only exacerbated the tensions created by economic competition. Shrimpers reported that they were often assailed with racial slurs and called “Viet Cong,” “VC,” and “Charlie”—terms that once described Vietnamese Communists now being used to address Vietnamese immigrants, many of whom had fought against the Communists, and nearly all of whom had risked their lives to escape Communist rule.

Due to miscommunications and misunderstandings, hostilities amplified into violent confrontations between Vietnamese and white shrimpers in Texas and Louisiana. In 1979, Seadrift, a town with a population of 1,250 on the southern Texas coast, was the scene of an argument that ended with the violent death of a white shrimper. In 1981, worried about diminishing opportunities in the industry, white shrimpers in Texas alleged the Vietnamese were “overfishing” and encroaching on territories informally claimed by long-time local shrimpers. Some of the whites even sought out the Ku Klux Klan as allies. The KKK threatened the Vietnamese, and conducted a boat ride along the docks of Galveston Bay that terrified and angered not only the Vietnamese but many others in the area. On the boat, they donned white hoods, fired a cannon, screamed racial epithets, and displayed an effigy of a Vietnamese fisherman hanging from his neck. The Southern Poverty Law Center intervened and took the KKK to court, charging that they infringed on the Vietnamese shrimpers’ civil rights. The courts ruled in favor of the Vietnamese, and the Klan as well as the shrimpers they attempted to help were forced to back down.

The lawsuit against the KKK was a victory for the Vietnamese shrimping community, and during the next decade, they reached the pinnacle of their economic success in the industry. Vietnamese families along the coast were buying more boats and equipment, establishing retail and wholesale seafood businesses, purchasing new homes and cars, and sending their children to college.

However, their struggles weren’t over yet. In the last half decade, dockside prices for domestic shrimp have gone into steep decline, while U.S. shrimp imports have risen rapidly. In the past few years Vietnam’s shrimp industry, based on cheap, coastal shrimp ponds, has led a global surge in shrimp production that, between 1997 and 2004, has depressed world shrimp prices by about 40 percent. On top of this, the Bilateral Trade Agreement between Vietnam and the United States, signed on July 13, 2000, sparked a sharp increase in Vietnamese imports to the U.S. Tariffs on Vietnamese goods were slashed from an average of 40 percent to just 3 percent, and by 2003 the U.S. had become Vietnam’s largest trading partner, importing $500 million of Vietnamese shrimp annually. Meanwhile, the value of the U.S. shrimp harvest plummeted from $1.25 billion in 2000 to $560 million in 2003, a 50 percent drop. The average dockside price for Gulf shrimp dropped from $6.08 to $3.30 per pound during the same period. U.S. imports from Vietnam and other developing countries have increased so drastically that by 2003, 90 percent of the shrimp consumed in the U.S. was imported. In a survey conducted by researchers at Texas A&M University’s department of wildlife and fisheries sciences, a majority of Texas fishermen strongly agreed with the statement that “Imported shrimp cause dockside prices to be lower.”

On Shrimp Imports, Strange Political Bedfellows

Important players cross ideological lines in the debate over shrimp imports from Vietnam and other countries.

CATO INSTITUTE—In a piece entitled “Big Shrimp—A Protectionist Mess,” Cato policy analyst Radley Balko criticizes the U.S. government’s largesse toward the American shrimp industry, which he scorns as “Big Shrimp.” Balko claims this proves that “the fight for free trade isn’t about protecting big business at all,” but rather standing up for American consumers who want cheap shrimp. Balko, however, makes no mention of “big businesses” involved in shrimp importing.

AMERICAN SEAFOOD DISTRIBUTORS ASSOCIATION—An industry group representing importers, wholesalers, retailers, and distributors who account for more than 80 percent of seafood sold in the U.S. The ASDA has teamed up with restaurant trade groups, soybean producers (who sell feed to overseas shrimp producers), the Consuming Industries Trade Action Coalition (CITAC), and high-powered, Republican-connected lobbying firm Akin Gump to form a “Shrimp Task Force” dedicated to fighting high tariffs on imported shrimp. The task force often refers to duties on imported shrimp as a “shrimp tax” on American consumers.

FUND FOR RECONCILIATION AND DEVELOPMENT (FFRD)—describes itself as “an independent non-profit organization seeking normal economic, diplomatic, and cultural relations between the U.S. and Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam.” The FFRD defends the trade and environmental record of the Vietnamese shrimp industry. Andrew Wells-Dang, the group’s Hanoi representative, argues that “the rules of the global economy, as enshrined in the WTO, are already tilted in favor of the strong over the weak. Unfair trade practices enabled by US anti-dumping laws deepen the injustice, taking away from the baby shrimp to give to the jumbo.” In particular, the FFRD opposes the Continued Dumping and Subsidy Offset Act—known as the Byrd Amendment after its major sponsor in the Senate, Robert Byrd (D-W.Va.)—under which tariffs collected in anti-dumping cases are turned over directly to U.S. producers. The FFRD calls this “a direct transfer from Third World farmers to the U.S. shrimp industry.”

ACTION AID—VIETNAM—Part of the U.K.-based NGO Action Aid International, Action Aid—Vietnam argues that U.S. anti-dumping actions could cause thousands of Vietnamese farmers to fall back into poverty. Vietnamese shrimp, the organization contends, is “highly competitive and affordable in the U.S.,” not because of illegal subsidies or dumping, but due to “enormous favourable conditions such as natural advantages, modern aquaculture techniques, and low labour cost.”

SOUTHERN SHRIMP ALLIANCE—An organization of American shrimpers in the Southeast, the SSA accused six countries of illegal dumping on the U.S. market, “sometimes below the cost of production,” and successfully sued to have the Commerce Department sanction the shrimp-exporting nations. The Alliance points out that “while the wholesale price of shrimp dropped 42 percent, shrimp entree prices actually skyrocketed as much as 28 percent between 2000 and 2003,” and accuses “shrimp middlemen” of pocketing $4.2 billion in resulting profits.

PUBLIC CITIZEN—In 2004 Ralph Nader’s organization launched a campaign to warn against the health and environmental dangers of farm-raised shrimp (the method in most shrimp exporting countries, including Vet Nam). “Shrimp farms produce a wretched cocktail of chemicals, shrimp feed and shrimp feces,” the campaign’s director, Andrianna Natsoulas, says in a press release, which goes on to claim that “Wild-caught shrimp from U.S. seacoasts such as North Carolina and California do not pose the same health risks as farm-raised shrimp.” The Shrimp Task Force has happily tied Public Citizen (which it refers to as an “anti-trade” organization) to the American shrimp industry, accusing the Nader group of an elitist program to make shrimp once again a rare (and presumably expensive) delicacy.

—Gary Ashwill

Evidence suggests that the crunch has afflicted Vietnamese-American shrimpers more than others; the Mobile Register reported in April 2005 that “most of the hundreds of [shrimping] boats repossessed over the past three years belonged to Asian Americans.” Some families have already given up their businesses and taken up new lines of work; others question how much longer they can stay in the shrimp industry. Dung Tran and his wife Ngoc own several boats and a wholesale seafood business in Kemah, Texas. Their losses in the last five years have them seriously considering a new business altogether. “We know a lot of people who left. We plan on selling our boats to buy chicken farms. We don’t make the money like before. We will close the wholesale business at end of this year. The only way we stay alive now is from people who live in Houston and come to our boats to buy direct from us.” Dung and Ngoc are unique because they have the resources to get out. The majority of Vietnamese shrimpers do not have the funds or assets to leave. “Many [Vietnamese-American shrimpers] can’t speak English and have no other skills. They have nothing to fall back on,” says Kim Nix, a community activist and advocate for Vietnamese shrimpers. Shrimping is a way of life for them, and they have no other alternatives.

Dang Nguyen entered the business as a shrimper on his brother’s boat when he arrived in the U.S. in 1982. He recalls the turmoil of the past, but has never left the industry because he was more concerned with making money to bring over the wife and two children he left behind when he escaped Vietnam. Now he, his wife, and eldest son work side by side on the docks in Galveston, Texas. “This is our life. This is the only thing I know how to do. I don’t have education. My wife doesn’t have education. We don’t have the money and [we’re] too old to start something else.” Their second son dropped out of the University of Houston to work full time as a retail manager to help his family make payments on the loan they took out years earlier to buy the boat. They wonder what they will do if things don’t get better.

In 2003, an industry trade organization, the Southern Shrimp Alliance (SSA), asked the federal government to impose tariffs against Brazil, China, Ecuador, India, Thailand, and Vietnam. The SSA accused these six countries of deluging the U.S. market with shrimp at artificially low prices supported, it argued, by government subsidies illegal under international trade agreements. Within the SSA, white and Vietnamese shrimpers have come together in a sometimes uneasy alliance. SSA spokesperson Deborah Long calls Vietnamese-American shrimpers “very supportive of the antidumping cases.” Their story, she says, can stand in for “the entire U.S. shrimp industry”: small entrepreneurs “with a long family history of fishing for their livelihoods” watching their businesses wither away under the onslaught of globalized competition.

And yet most of them are reluctant to be too vocal against Vietnam, a country some still consider home. Long confirms that Vietnamese-American representatives of the SSA have declined to participate in press stories that single out Vietnam. Thanh Nguyen, a shrimper in Kemah, Texas, for over fifteen years, says, “It is hard to think about because I know some people in Vietnam from my village who make money in [the] shrimp business. If we cut off the business for Vietnam, I am afraid for them. They will have to look for other work again. But it is same for me, too. I will lose my job if we can’t sell the shrimp we catch for a good price.”

Vietnamese-American shrimpers seem to blame China more than any other country. This is not surprising, given China’s frequent role in Vietnamese history as invader, as well as more recent memories of its support for the North during the “American War,” especially among refugees from Phuoc Tinh who had twice fled the Communists (though the two regimes went their separate ways after the fall of Saigon, fighting a war in the late 1970s). Moreover, ethnic Chinese living in Vietnam have often been stereotyped as avaricious merchants. These negative ideas are reflected in the rumors that have spread among the Vietnamese-American community about China. Vietnamese-American shrimpers believe China is doing the most damage to domestic shrimp prices. Several shrimpers in Seabrook, Texas, insist that China exports much of its shrimp through Vietnam; thus, they claim, it is not Vietnam dumping shrimp on the American market, but rather China.

In December 2004, the U.S. Department of Commerce agreed with the SSA that the six countries were guilty of dumping shrimp on the U.S. market and instituted tariffs against all six, though at a much lower rate than the American shrimpers had wanted. Duties ranged from 4 to 25 percent for Vietnam, while higher duties were imposed on Chinese shrimp, from 27 to 112 percent. Vietnamese-American fishermen saw this as vindicating their suspicions about China.

Whether their claims are true or not, it does appear that the duties on Vietnamese shrimp are still low enough that business has not been severely disrupted. According to the Network of Aquaculture Centres in Asia Pacific’s December 2004 newsletter, the president of the Vietnam Association of Seafood Exporters and Producers (VASEP) told local reporters that business contacts between U.S. customers and Vietnamese seafood companies have returned to normal. In another instance reported in the newsletter, an order worth $2 million was placed by a U.S. customer with the Ho Chi Minh City Coastal Fisheries Development Corporation a few days after the tariffs were determined. Its director announced that 23 other regular customers of the company began seeking information for future orders through e-mails.

News of resumed business between U.S. importers and Vietnamese shrimp companies worries American shrimpers. Although the higher tariffs will certainly have some effect, will it be enough to spur sales of domestic shrimp? Will the SSA’s anti-dumping suit really help its members in the long run? Domestic shrimpers have only just embarked on the journey to rebuild their industry. One of the SSA’s ideas is to market domestic shrimp as “American wild shrimp,” to distinguish it from pond-grown imported shrimp. The advertising campaign, which has featured celebrity chef Emeril Lagasse, conveys the message that domestic shrimp caught in its natural habitat is a healthier, tastier product than farm-raised shrimp. Van Ngo, a member of the Vietnamese American Fishermen’s Association and a long time fisherman from Port Arthur, Texas, has high hopes for the new marketing direction: “I always thought I have to do what I do because I don’t have an education. I had no chance to learn something new. But now we need to learn how to do our business better so people will buy our shrimp again. I have a chance to learn to do something in a new way. I am excited and hopeful.”

It may be too late. In addition to falling prices that have already devastated the industry, Vietnamese shrimpers now have to deal with new licensing restrictions that could limit their ability to recover. In the mid-1990s, the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department (TPWD) became concerned with the dwindling wild shrimp population in the Gulf. Dr. Larry McKinney, director of the TPWD’s Resource Protection Division, put it plainly: “The fishery is headed for a collapse.” Recruitment over-fishing was the problem; in other words, shrimp were being taken from the waters faster than they could reproduce. Soon, the Gulf’s shrimp population will hit an all-time low mark, and it may never rebound.

With this crisis in mind, individual states as well as the federal government have closely restricted the shrimping industry in recent years, closing off certain areas, imposing seasonal closures and catch limits, regulating the size of mesh in nets (so as to minimize dangers to sea turtles and fin fish), and “retiring” shrimping licenses. And in December 2004, the Gulf of Mexico Fishery Management Council limited the total number of federal shrimping licenses (for fishing in federal waters) to 2,700, the number of boats that were registered in December 2003. This will disproportionately affect Vietnamese-American shrimpers, as most aren’t even aware they need a federal license (the rule required such licenses was instituted in 2002). Perhaps more importantly, the large number of Vietnamese-American shrimpers who have had their boats repossessed in recent years may now be unable to get back in the industry.

The de facto resurgence of racial exclusion through limiting licenses, combined with the economic pressures of globalization felt through the whole industry, may be enough to put an end to the Vietnamese shrimping communities of the Gulf coast. But some, like Chanh Le, hang on still. Their profits are marginal, but they manage to continue doing the only thing they know. They have fought fiercely against many different challenges, and they are determined to persevere.

Tags

Thao Ha

Thao Ha is a doctoral student in the sociology department at the University of Texas at Austin. She was born in Viet Nam and grew up in Houston, Texas. (2005)