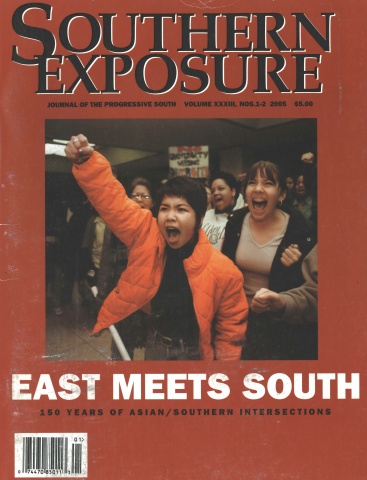

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 33 No. 1/2, "East Meets South." Find more from that issue here.

The South has long been crucial within the U.S. military’s strategic web of installations and outposts around the world. North Carolina in particular has had its contemporary history shaped by the presence of three bases: Camp Lejune, Pope Air Force Base, and the massive Fort Bragg complex next to Fayetteville that houses a tenth of the U.S. Army’s active duty force, including the 82nd Airborne Division. The bases have positioned eastern North Carolina as a primary exporter of soldiers for nearly every American military action since World War II. With these actions came the establishment of even more bases elsewhere: forward airstrips and relay points, listening posts and supply depots all circulating American military personnel from the frayed and distant edge of U.S. foreign policy interests and back again to stateside assignments at places like Fort Bragg.

Since World War II, the majority of these overseas installations have been in Asia with Japan poised as the most strategic site for America’s growing military apparatus in the region. The Occupation of Japan following the 1945 surrender ensured that the newly reconstituted nation would be politically predisposed towards serving the future needs of U.S. policy through the generous accommodation of an extensive military presence. By the end of the Korean War Japan found itself thick with nearly 600 American bases, a presence that has slowly receded to eight major bases stretching from the far north and pooling in a heavy concentration in Okinawa, with Kadena Air Base continuing to serve as the largest U.S. base on foreign soil.

The robust logistical and personnel networks of the military, which have circulated materiel and soldiers out to these bases, have found a second network developing along their seams. This is an organic network, threading from overseas duty stations back to flimsy stateside military housing and the spare, tidy developments that cluster just outside the main gates of bases. This is a circuit of intimacy and family that casts fine tendrils around the mission-oriented traffic of national defense. An unintended consequence of the sprawling reach of U.S. militarism is that the South has become home to a particular type of community: the Asian wives of American men who shipped off as soldiers to Korea, the Philippines, Thailand, Vietnam, or Japan.

The women move with their husbands and growing families from one duty station to another, sometimes waiting for months at a time while their husbands are on indefinite temporary assignments elsewhere, consoling one another, sharing information about schools, hospitals, banking and the minutiae of everyday life in order to acclimate to new systems, unfamiliar bureaucracies, and strange geographies. Japanese women in Fayetteville have been a visible and growing presence in the military community since the late 1950s and have thrived at the precise point where the U.S. military, the American South, and Asia triangulate.

At an afternoon meeting of the Japanese-American Kneda Kai (Maple Society) nine women gathered around the table in Yasuko Kelly’s modest brick ranch house close to Ft. Bragg’s main gate. A large, ornate sensu, a Japanese fan, decorated the wall facing the kitchen door through which Yasuko passed mugs of black coffee and cups of green tea. Seventy-two-year-old Ruiko Long pulled the ashtray closer as she lit a slender menthol cigarette, listening to the other women discuss an absent member’s sick daughter. The group had met today to plan for the upcoming traditional Japanese natsu matsuri, the summer festival held in July. They put their agenda aside for awhile as Yasuko explained my interest in the Japanese community that had formed in Fayetteville. Chieko Mitsui laughed as she said, “You know, all of us have been in America longer than in Japan! We’re Americans!” The older women arrived in the U.S. during the tumultuous years of the Civil Rights struggle and soon after the war in Korea, a confluence of events that marked them out as problematically different in multiple ways. They were “war brides,” typecast through popular culture depictions such as the Marlon Brando feature, Sayonara (1957). They were undifferentiated “Orientals”—the face of the enemy in America’s long series of wars throughout Asia. They were foreign nationals with intimate and risky ties to the U.S. military. They were non-whites married to white men in the Jim Crow South.

“A long time ago, some kids at the bus stop would say, ‘Look, it’s Chinese!’ All the time people just call us Chinese,” Chieko recalled. She had married an enlisted man in 1954 in Tokyo and when they arrived in America, they confronted the anti-miscegenation laws of her husband’s home state, Virginia. They had to register their marriage in Washington, D.C. Chieko held her cigarette in mid-air, squinting through the smoke as Satchiko agreed softly. “I was doing accounting in a supply depot. The sergeant major reassigned my husband before we got married, trying to separate us. He was looking at me, telling me not to do this.” After eight months the paperwork was approved.

“We go to the American Consul and we say, ‘I do,’ and that was the saddest wedding. After that we got the orders to come back to the States. . . . I cannot go home because my father disowned me, but I can call my mother during the daytime. She talked to my father and he agreed that if we had a Japanese wedding. . . .” Satchiko’s voice became faint, but she continued, “We didn’t have money, but we thought, ‘If that’s what he wants!’ Because it’s my father and if we do it, after that he can tell his friends his daughter was married properly. We needed the money to come to America, but. . . . Later my husband even lost his Top Secret Clearance because of me.”

Tamako, younger than Chieko and Satchiko, had married an African-American soldier stationed in Okinawa. Pausing briefly after Satchiko had finished and staring straight ahead, she said loudly, “I just ran away. Seventeen years later I finally went home. I was crossing a lot of boundaries . . . even here, in the U.S., people have different eyes and look at me and my husband differently. My younger sister was ashamed of me, because of who I married, and she didn’t want me to come home. My parents are both passed and they never saw my husband. Japanese are strict, and don’t want to mix blood. Even high class and low class can’t mix in Japan.”

As the harsh logic that marked different bodies with different consequences mutated across the globe, it was entangled through love and familial care. Kuniko emphasized that their parents were trying to shield their daughters from the loneliness of forever leaving Japan and the fierce gossip that was sure to fester around them. “Yes, my older sisters said, ‘You’ll have no education and be dependent only on your husband and won’t know anybody . . . in a way they were trying protect our happiness.” Satchiko nodded while Chieko expanded the issue further. “And they said, ‘Your children will be mixed breed—ainoko [in-between child]!’ Our parents worried what other people would say.”

Over the course of their lives in America, the women stressed, they had seen things change. Their children had been able to grow up as Americans, though not entirely without difficulty, as Tamako pointed out. “I’m married to a black man and I have one daughter. I’ve watched her since she was little and all her friends were white. When she starts junior high school, her white friends are trying to match my daughter with other boys, but only black boys. If my daughter had a white boyfriend, her white girlfriends didn’t like it. Eventually they kind of shy away and the friendship was kind of gone. Some people have the idea that mixed relationship isn’t good.”

Despite the difficulties around race they and their children have been forced to navigate, the women viewed “American” as an ideal identity. Though they celebrated a few traditional Japanese holidays in their homes, they largely had not emphasized Japanese culture with their children even as they themselves felt increasingly distant from Japan. “We are all museum women!” Chieko chortled as she exhaled a thick cloud of smoke. “Japan has changed but we only remember it the way it was when we were twenty-four.” Kuniko, now an American citizen, described the complex and ambivalent feelings the space of Japan provokes for her. “I have such a strange feeling when I go to Japan, at Narita Airport when I have to go in the Foreigner Lane. I am like a gaijin—an outsider! It feels funny.” Abruptly switching to emphatic Japanese, her tenor conveyed the painful duality she still contends with. “Kankaku ga kirai da.” I hate the sensation.

None of the women want to move back to Japan, nor do they want to move to places like Los Angeles or Seattle with their established Asian communities. Civilian life in small town America is equally unappealing. Setsuko tried to live in Florida with her husband after he retired but she was lonely and the way of life away from military culture was strange and uncomfortable. Finding it hard to settle into her husband’s ordinary hometown, Setsuko insisted they move back to Fayetteville. “Our husbands are American. They can get along anywhere, but we have our friends here. That’s why there are so many old Japanese women here. This is what we know.”

The Japanese women who form this vibrant community still shop at the Post Exchange and the commissary with its shelves well-stocked with miso, tofu, nori, and sushi rice pointing to how the everyday life on the base has shifted to accommodate the tastes and demands of the steadily growing population of Asian women. The rhythms of Fayetteville are familiar and the years of living behind the barbed wire of military bases has created a unique culture largely unintelligible to the “Japanese- Japanese,” as Chieko calls them, who live in the suburbs of Raleigh and Cary and work on the landscaped grounds of corporate campuses in Research Triangle Park. Those families have arrived here through a different network than the military circuits which women such Chieko and Tamako have traveled. These professionals and their families arrived in the South via the sleek networks of globalization and enjoy class privileges quite unfamiliar to the Japanese wives of enlisted men.

The military continues to serve as the organizing feature for the landscape these Japanese women inhabit. Chieko acknowledges the powerful, mediating presence of the military, proclaiming, “It may be the South, but it’s a military town!” The South has been filtered and rearranged by the inexorable, uniform structures of military life that insulate dependents and soldiers from the intense shocks of the local that await beyond the base culture and its near vicinity. The military networks have impacted the South by forging familial links that stretch out as far as American political and economic interests extend. In turn it is exactly through these military networks that some of the most complex and intimate exchanges continue to occur at the level of individual, everyday relations and where identities and local cultures are refashioned. The women of the Maple Society, along with the numerous other wives of Asian origin, have significantly reshaped the nature of military communities such as Fayetteville through their struggle, adaptation, sacrifice, and resistance.

Tags

Dwayne Dixon

Dwayne Dixon is a graduate student in the Department of Cultural Anthropology at Duke University studying youth culture in Japan. He is the son of a career Army officer and has lived on numerous military bases, including Fort Bragg. (2005)