This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 33 No. 1/2, "East Meets South." Find more from that issue here.

On a sunny day in late September 2004 close to 1,000 Americans of Japanese descent traveled a southeastern route from Little Rock, Arkansas, to the section of the state known as the Delta for its fertile lands and proximity to the Mississippi River. For many of them this was a return trip, after sixty years, to the place the federal government incarcerated them during World War II for looking like the enemy.

Following Japan’s surprise attack on the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, a long history of discrimination, suspicion, and prejudice against Japanese American residents combined with the attack to create fear and near hysteria, especially on the West Coast. As Japan’s military forces swiftly moved through Guam, Wake Island, and the Philippines, many Americans feared that Japan would invade the West Coast and that Japanese Americans would assist the enemy. The FBI went door-to-door in these areas rounding up immigrant Japanese-American community leaders while the Federal Reserve froze all bank accounts held by Japanese immigrants. Although no creditable evidence existed, then or now, that any Japanese Americans posed a threat to national security, residents of California, Oregon, and Washington demanded protection from what they saw as a possible enemy force in their own backyards.

In this climate of fear and wartime hysteria, and at the urging of Western Defense Commander Lt. Gen. John DeWitt, on February 19, 1942, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which empowered the Secretary of War and the military to establish zones from which certain individuals or groups (i.e., Japanese Americans) could be excluded. Less than a week later DeWitt created Military Zone One encompassing the western portions of Washington, Oregon, California, and Arizona. Exclusion notices appeared on utility poles and Evacuation Sale signs hung in Japanese American-owned store windows.

None of us really knew where we were going. They never really told us where, they just said to be ready. They sent us a notice, telling us to assemble . . . at the old Union Church, and it was walking distance for us. All the soldiers were lined up and the buses were lined up. My husband thought that we were going to go up to the desert. We ended up in Santa Anita [Racetrack]. We thought it was going to be miles and miles away, so when we got on the bus and we got to Santa Anita, I was stunned.

Miyo Senzaki, Rohwer

Executive Order 9066 effectively forced more than 110,000 people of Japanese descent, 70% of whom were American citizens, from their homes and required them (if they did not have the capital to pay mortgages and taxes) to dispose of their businesses, their houses, and most of their personal possessions at a great loss. First confined in “assembly centers,” such as the Santa Anita Racetrack, the government then shipped the Japanese Americans to ten “war relocation centers” located in remote areas of California, Utah, Idaho, Wyoming, Arizona, Colorado, and Arkansas.

We were put on trains. And I remember that, because even though I was only about eight, nine years old, it’s the first train ride I ever took. And I remember the soldiers, the guards on the train, because we had to stop—it was a long distance from California to Arkansas—stop every now and then to get off the train and exercise, and get back on. But it was like a military maneuver.

Paul S. Sakamoto, Rohwer

In the summer of 1942, two of these “war relocation centers,” Jerome and Rohwer, emerged from the swamps and forests of the Arkansas Delta. Neatly ordered rows of military-style barracks dotted the horizon and guard towers rose above the flat terrain. Japanese Americans began to arrive in southeast Arkansas by train from California in September 1942. Displaced from their homes and lives on the West Coast, the internees experienced the upheaval individually; each person tells a different story. This is the story of the Japanese-American experience in World War II Arkansas.

On September 28, we boarded a train at Santa Anita and after four days of travel we arrived at Rohwer, Arkansas. I was disappointed in this camp at first sight but I am readily getting used to it. I now reside at Block 15, Barrack 9, Unit A.”

Jack Miyaki, Rohwer high school student

Our father had told us that we were going for a “long vacation in the country.” I believed him. I thought it would be a wonderful adventure. Our father told us we were going to a camp called Rohwer in a faraway place called Arkansas.

George Takei, Rohwer

Arkansas in the 1940s was a rural, farming state where animals and humans still supplied the greater part of the labor necessary to plant, cultivate, and harvest the fields. Most Arkansans, white and black, lived and worked as tenant farmers or sharecroppers on land owned by someone else. This system kept workers continually in debt to landowners, unable to put aside enough money to buy land or get another job. In the Arkansas Delta, the population was desperately poor. Many people, black and white, lived in shacks without running water, indoor toilets, or electricity. Debilitating disease was common, and health care facilities were limited. Jim Crow dictated the rigid segregation of society and the economy by race. Few communities offered formal education beyond the eighth grade, and black schools, where available, lagged far behind white schools in their funding which resulted in inferior facilities, supplies, and curriculum.

During the Depression the Farm Security Administration, a New Deal agency, came to southeast Arkansas and purchased tax-delinquent lands in Chicot, Drew, and Desha counties to develop as subsistence homesteads for poverty-stricken farmers. When the government officials running the War Relocation Authority needed land to build the centers in remote, isolated locations with easy access to existing railroads and the potential for agricultural endeavors, they remembered Arkansas.

Life Interrupted

Many Japanese Americans were long reluctant to speak of their incarceration because of the shame, but the campaign for redress combined with an aggressive educational campaign about Executive Order 9066 and Japanese Americans during World War II has begun to reverse that trend. In late September 2004, Life Interrupted: The Japanese American Experience in World War II Arkansas, a partnership of the University of Arkansas at Little Rock’s Public History program and the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles with major funding from the Winthrop Rockefeller Foundation, invited the survivors of Rohwer and Jerome (and the other War Relocation Centers) back to Arkansas. They came, surrounded by family members, to participate in Camp Connections: A Conversation about Civil Rights and Social Justice in Arkansas. Over the course of three days the former inmates and their families learned more about their “Arkansas experience” and its place in the larger context of U.S. history through exhibits, panel presentations, speakers, curriculum kits, and a documentary, Time of Fear, which aired on PBS in May. On the last day of the conference they returned home to the Delta, frequently fanning out across fields to stand in their barracks’ exact locations.

For the Japanese Americans (and their families) who attended, the fellowship and memories renewed, and the knowledge gained from Life Interrupted helped to resolve years of guilt and confusion. Many younger generation Japanese Americans (children, grandchildren, and even great-grandchildren of those who had been in camp) learned about their family’s World War II experiences for the first time.

For Arkansans, an important chapter of their state’s history emerged from anonymity. Not only did the extensive press coverage of Life Interrupted and the Camp Connections conference in particular, rate as one of the top ten news stories in Arkansas by an Associated Press poll; the only state-wide daily newspaper, the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette featured the project on its September 23, 2004, editorial page. On that day readers could learn about the conference, the exhibits, and the educational materials for Life Interrupted as well as two opposing commentaries on Michelle Malkin’s controversial book In Defense of Internment. The history of Jerome and Rohwer will remain visible throughout the state for the foreseeable future thanks to training almost 600 teachers in the curriculum packages and lesson plans (available at http://www.ualr.edu/lifeinterrupted/curriculum/index. asp) developed by the Life Interrupted Education Director and nine master teachers. Those teachers reach approximately 41,000 students of Arkansas history, geography, fine arts, and language arts.

The WRA centers at Jerome and Rohwer housed approximately 17,000 Japanese-American inmates between September 18, 1942, when Rohwer opened and November 30, 1945, when it closed. Jerome opened on October 6, 1942, and closed on June 30, 1944—it had the distinction of being the last camp to open and the first camp to close. Inmates assigned to Rohwer came from Hawaii, as well as Los Angeles and San Joaquin counties, California, and totaled 8,475 at peak population. In addition to inmates from Los Angeles, Fresno, and Sacramento counties in California, Jerome housed inmates from Hawaii and totaled 8,497 at its peak.

The WRA designed the relocation centers to be self-contained and mostly self-sufficient communities, complete with hospitals, post offices, schools, warehouses, offices, farmland, and living quarters. Organized in military fashion, each camp was built on a grid system with barracks grouped into blocks. Each block contained ten to fourteen barracks; a mess hall with a kitchen, storeroom, and dishwashing area; toilets for men and women; and a recreation hall.

With sewer systems, water treatment plants, and electricity, the Jerome and Rohwer camps featured amenities ironically unavailable to many Delta residents. These advantages, coupled with three meals a day supplied by the U.S. government, spurred anger and resentment among some white residents of the Delta. Families in McGehee watched in astonishment as mess-hall table scraps, including almost-whole hams, bread, and vegetables, became pig slop. Although African Americans sometimes received the opportunity to work at Jerome and Rohwer, black Arkansans generally had little interaction with the Japanese American internees.

[Rohwer was] far enough south to catch Gulf Coast hurricanes, far enough north to catch midwestern tornadoes, close enough to the [Mississippi] river to be inundated by Mississippi Valley floods, and lush enough to be the haven for every creepy, crawly creature and pesky insect in the world.

Eiichi Kamiya, Rohwer

[Arkansas] was very cold. I was there six months; from about the end of October to April, so it got very, very cold. I had not experienced such a cold climate. The camp was supposed to be a mile square. I don’t know if it was, but it was a square, I think. We lived on the one end of the camp. . . . So we had to walk—of course, there was no transportation. We just walked everywhere. It was so bitterly cold. I remember that so well because our knees ached from the cold to walk to our jobs.

Haruko (Sugi) Hurt, Rohwer

With its humid summers and icy winters, acclimating to the Arkansas Delta proved difficult for the Japanese Americans. The tarpaper-covered barracks absorbed heat in the summer and made the structure unbearably hot while providing little insulation from the freezing temperatures in the winter. Wall partitions inside the barracks separated the apartments but they only reached to the eaves, limiting privacy. The wood flooring had large gaps between the boards, allowing dirt and bugs into the barracks. Each unit came equipped with a heating unit fueled by coal or wood; a bare light bulb; army cots, blankets, and mattresses. Living quarters provided neither running water nor cooking facilities.

These “government-issue” camps imposed a military lifestyle with group bathrooms and showers without dividers for privacy. The shower and bathroom buildings resembled a capital “H,” with a laundry on one side and the men’s and women’s bathrooms on the other with the hot water heater in the crossbar. Since inmate families could not eat together in their quarters, children ate with their friends in the mess hall, and sometimes parents only saw their children in the early morning before school and in the late evening before bedtime.

Young people just could go to the mess hall and eat their three meals with their friends. They didn’t have to go with their family. . . . There was no family life as such in camp, because family didn’t eat together, didn’t have to.

Haruko (Sugi) Hurt, Rohwer inmate

Communal living posed problems for the inmates, especially in the way it caused the breakdown of family structure and parental authority. Standing in line became a way of life for inmates. They stood in line to get on the train to come to Arkansas; they stood in line to get off the train at Rohwer or Jerome; they stood in line to register, to eat, to shower, to use the restrooms, to get ice, to get wood or coal; and they stood in line to get back on the train to leave Arkansas and go to their next destination, whether it be another relocation center or Chicago or Cleveland.

To me, the tall guard towers and the barbed wire fence that incarcerated my family and me became part of my normal landscape. . . . It became normal for me to line up three times a day to eat in a noisy mess hall. It became normal for me to go with Daddy to a communal shower and bathe with many men. It became normal for me to go to school in a black, tarpaper-covered barrack. I learned to recite the Pledge of Allegiance to the flag within sight of armed sentries watching over us. I was too young to appreciate the irony as I recited the words, “with liberty and justice for all.”

George Takei, Rohwer

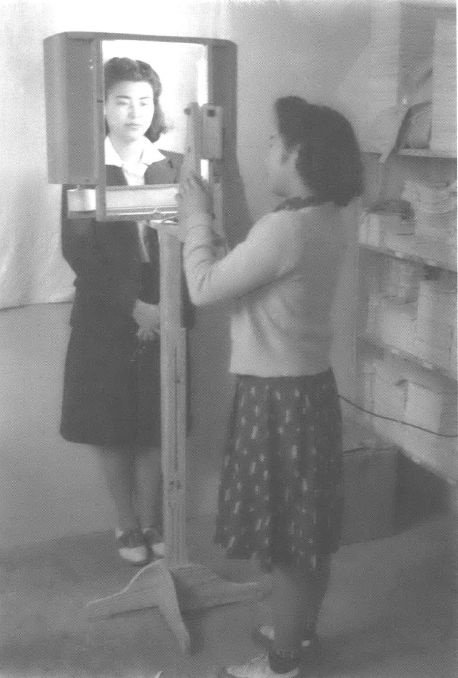

Despite their forced removal from the West Coast and placement in what were effectively prisons, inmates at Rohwer and Jerome refused to assimilate totally into this pseudo-military culture. They held onto the Japanese language as well as symbols and cultural practices such as ikebana, flower arranging, calligraphy, embroidered wall hangings, and kimonos. Inmates also created new routines in their daily activities. Children attended camp schools while younger adults worked in WRA administrative offices and other facilities. Older adults tended small garden plots wherever they could find space, raising both vegetables and flowers; many worked in the fields cultivating crops that eventually helped feed all ten WRA camps. Young people attended dances, worked on writing, drawing, editing and publishing the daily center newspapers, the Rohwer Outpost and the Denson Tribune, or played baseball, basketball, and football, along with traditional Japanese sports such as judo and sumo wrestling. Both Buddhist and Christian worship services were available. Life went on, in the face of adversity, within barbed wire and shadowed by guard towers.

It was life beyond barbed wire, however, that distinguished Rohwer and Jerome from the other eight camps. Inmates from all the camps frequently applied for, and received, permission to travel into nearby towns and cities for shopping and recreation. But in Arkansas excursions to Dumas, Pine Bluff, and Little Rock not only provided a respite from the monotony of camp life, they gave these Japanese Americans from the West Coast a powerful sense of segregation in the rural South. Confusion arose among inmates, many of whom had experienced racial segregation in California, about their place in the racial structure of the Delta. Was their place at the front or back of the bus? Should they use the white or colored bathrooms? Could they drink from the white drinking fountains?

I got on the bus and my first decision I had to make outside of camp was “Where do I sit? ” The white people sat in the front of the bus. The blacks were in the back. And so I got on and I thought, “Gee, I don’t know where should I sit?” So I said, “Gee, we were confined so long and we were discriminated so much that maybe I’ll be considered black” So I went to and I sat in the black area. The bus driver stopped the bus and he says, “Hey, you gotta sit in the front.” So I got up and moved, but I didn’t come way in the front either, I sat right by the dividing line.

Ben Tsutomu Chikaraishi, Rohwer

If the Japanese Americans were unsure of their place in the segregated South, Arkansans weren’t—it was obvious that the “Japanese” were not black. This made travel beyond the Delta easier and so some young women made chaperoned bus trips across the river to Camp Shelby in Hattiesburg, Mississippi, for dances with Japanese-American soldiers courtesy of the United States Army. A Boy Scout Troop from Stockton, California, temporarily residing at Jerome, held a jamboree on the banks of the Mississippi River with a troop from Arkansas City. Many of the Stockton Scouts remember they had uniforms while the Arkansas City troop didn’t; a few inmates gave their uniforms away. Perhaps the most remarkable excursion outside camp was made by the distinguished artist, Henry Sugimoto. In February 1944 Sugimoto exhibited his paintings and drawings of daily life in Jerome and Rohwer in a one-man show at Hendrix College in Conway.

In accordance with Administrative Notice No. 289 . . . you are hereby advised that you are scheduled to leave this Center during the week of November 5-9, 1945 . . .

Letter from Ray Johnston, Rohwer Project Director, October 22, 1945

In December 1944, the Supreme Court ruled that American citizens of Japanese ancestry who signed a loyalty oath could no longer be detained behind barbed wire. The War Department subsequently rescinded the order barring all Japanese Americans from the exclusion zones, and the War Relocation Authority began to close the relocation centers. Japanese Americans were dismissed from the internment camps as peremptorily as they had been summoned. Each inmate received $25 and transportation to the location of their choice. Most found “resettlement” difficult to deal with, especially with few savings to live on, no homes or property awaiting their return, and the shame they felt from being imprisoned. At Rohwer, the last Arkansas camp to close, some elderly inmates balked at leaving because they could not face starting life over again. Other camps reported inmate suicides.

Of the more than 16,000 Japanese Americans relocated to Arkansas during World War II, only a handful remained after the war. Most Japanese Americans refused to resettle in the South out of fear they would be “classed and treated like the Negro.” In a May 1945 letter to WRA Director Dillon S. Myer, Rohwer Project Director Ray Johnston stated, “The evacuees strongly fear that [the ‘caste’ system of the South] will reduce them to the economic level of the poorer whites and Negroes, and to the social level of the Negroes as a caste group. This is no doubt the basic cause for the general lack of interest to date in the South as a relocation area.”

Most inmates chose to return home to California and Hawaii, though a few resettled in the Midwest. The American Friends Service Committee reported in early 1944 that “crude literature of vigilante-type organizations continues to be circulated” in California and that returning veterans demanded that “all persons of Japanese ancestry be forever barred from California soil and deported after the war along side of other subversive-minded aliens.” A year later, however, the American Friends Service Committee noted in their newsletter “that veterans’ organizations . . . have now swung over to support of the rights of Japanese American citizens, give full recognition to the distinguished service record of Nisei in the United States Army, and have rebuked instances of racial discrimination on the part of local posts.”

A farming cooperative located in Scott, Arkansas, persuaded some Japanese Americans from Rohwer to become sharecroppers. About eighteen families moved to Scott but only one family remained in Arkansas permanently—Sam Yada, his wife Haruye, and their two sons, Robert and Richard, who moved from Scott to North Little Rock in 1953. Yada opened a successful nursery and was one of the few voices in Arkansas to talk about the camps. To remind Arkansans about the legacy of Rohwer and Jerome, Sam Yada donated books about Executive Order 9066 and the relocation centers to libraries around the state. He also participated in a two-part documentary about Rohwer and his experiences in camp. Today Bob and Richard carry on their father’s work in keeping the memory of the internment camps alive, most recently raising money to conserve and restore the cement monuments and headstones in the Rohwer cemetery.

After the war, most of the physical traces of the camps’ existence disappeared when the federal government sold off the buildings, the equipment, and the land. Oats, soybeans, winter wheat, and cotton now grow where the Jerome and Rohwer Relocation Centers once stood. Today, little evidence remains of the incarceration of Japanese Americans that took place in southeast Arkansas during World War II. At Jerome, a smokestack from the hospital complex, two concrete tanks from the wastewater disposal plant and a former administration building are visible from U.S. Highway 165. Farmer and landowner John Ellington lovingly tends those remnants, along with a granite memorial erected by the JACL dedicated to the wartime experience of Japanese Americans. A cemetery and two cement monuments dedicated to Japanese-American soldiers during the war, along with two contemporary granite monuments, mark the site of Rohwer, while a smokestack remains visible across the cotton fields in the distance. Still owned by the War Relocation Authority through a bureaucratic error, in 1992 the cemetery at Rohwer was named a National Historic Landmark.

Imprisonment of Japanese Americans during World War II was the most serious government violation of civil rights since slavery. While no simple reason explains why it happened, in 1988 a Presidential Commission investigating possible redress for former inmates concluded that “the broad historical causes were race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership.” For many Japanese Americans, the experience created deep distrust in the government, and events immediately following the war did little to dispel it. In 1948 President Truman signed the Japanese American Evacuation Claims Act, which appropriated $38 million to reimburse Japanese Americans for “damage or loss to real or personal property” they experienced when forced to leave their homes and businesses. No provisions were made for lost income or profits. While approximately 23,000 Japanese Americans filed claims requesting $131 million in damages under the Act, in 1950 the government cleared 210 claims, and only 73 individuals received financial compensation.

It would be nearly forty more years before some measure of justice toward internees was achieved, and then it was partial and bittersweet. Although the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 finally included a formal apology to Japanese Americans for their wrongful imprisonment and provided a one-time payment of $20,000 to camp survivors, these measures could not erase the profound humiliation and pain suffered by Americans of Japanese ancestry.

The questions raised by the internment of Japanese Americans resonate strongly in our post-9/11 world. From the Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798 to the Patriot Act of 2001, the United States has always struggled with contradictions between national security and civil rights; the legacy of the Arkansas internment camps warns us of what can happen when we punish people for looking like the enemy.

Tags

Johanna Miller Lewis

Johanna Miller Lewis is Professor of History and Coordinator of Public History at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock. She has won numerous awards for exhibits that bring the history of civil rights to the general public. (2005)