This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 33 No. 1/2, "East Meets South." Find more from that issue here.

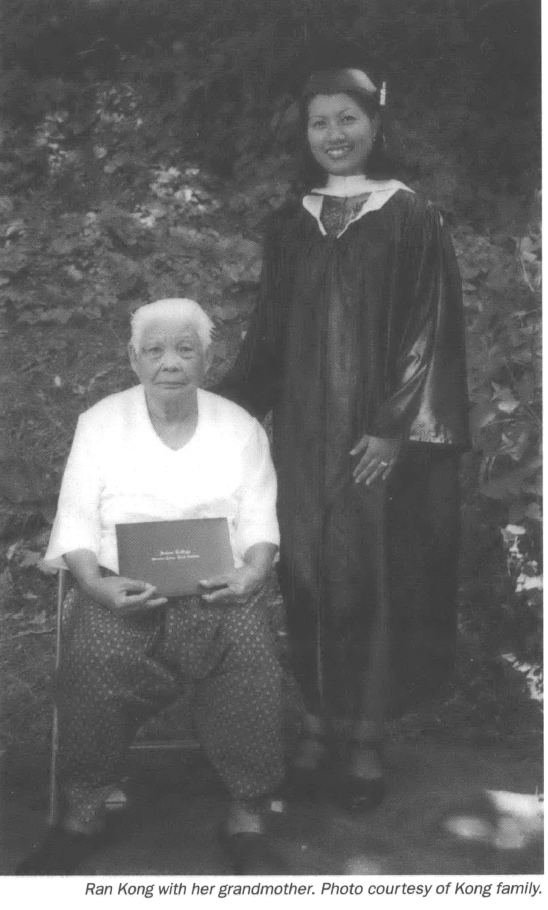

Ran Kong shared this story with me just after completing her first semester of college. Her parents fled Cambodia in 1980 and arrived in North Carolina as refugees in 1984. Ran was just four years old. The first member of her family to seek higher education, Ran won a scholarship at Salem College. She was part of a small group of Asian students attending this private, women’s institution in Winston-Salem. Although Ran grew up attending public schools, she spent much of her childhood at the Greensboro Buddhist Center learning traditional dance, participating in religious ceremonies, and absorbing Cambodian culture and traditions. Ran befriended me in 1992 when I began doing folklore research at the Greensboro Buddhist Center. The experience Ran relates in this interview shaped the way she sees herself as an Asian American in the South.

—Barbara Lau

BAL: I wanted to ask you to tell me a story that you told me a while back. Now that you’ve graduated from high school, you are now attending. . . ?

RK: Salem College [in Winston-Salem, North Carolina].

BAL: So tell me a little bit about meeting some of your fellow students.

RK: Salem is an interesting little college. A lot of its reputation is that it’s an elite school, you know, mainly white. White families send their girls there and they’re mostly well-off families and so they are starting to try to like, diversify the number of students in there. I remember a while back I was studying with one of my friends for my macroeconomics finals. We decided to take a two-hour break and just sort of like, talk about each other and this is at, maybe two o’clock in the morning. It’s supposed to be an all-nighter, and she was like, “Wow, I’ve never met anybody from Cambodia. The school that I went to was mainly all white and I’ve never really seen an Asian.”

A lot of people don’t even know where Cambodia’s at. A lot of the girls that go there are like, “You’re from Cambodia, where’s that at?” and I’m like, “Southeast Asia,” and they’re like, “Where’s that at?” So if you name some place like China or Japan, they’ll know. But you say Cambodia and they’re like, “Whoa, where?”

And so I started talking to her a little bit about my family, my culture, the war, how it is that I got here, what my family experienced on the way here, and she was just awed. She was like, “I’ve never heard anything like that.” And she told me a little bit about herself, about her family and what her plans for the future were. And we talked a lot about our marriage customs and I told her about arranged marriages in Cambodia and how my sister was arranged, and she talked about how she wanted her wedding to be, what her ideal wedding would be. So it was a nice exchange there at 2 o’clock in the morning.

BAL: Can you tell me the story about being with some other students where everybody had to do something or talk a little bit about themselves?

RK: Well, I live in Babcock dorm on the third floor and it’s really interesting how they paired me up. We took personality tests—“What do you want in your roommate?” “What are some qualities that you have?” And I had requested a roommate who had gone to school with me and she’s Ethiopian and her name is Urgaba. And so we got each other as roommates and we get along perfectly well. And near me there is a black girl and another girl who has some Honduran in her—I think her parents are half Honduran, so she is maybe like a quarter Honduran. And then down the hall from me there’s an Indian girl and one who is half Puerto Rican and there’s another girl who can trace her ancestry back to, I think, Scotland and then, you know, everybody else [is] mainly white.

And so there’s an interesting mix we have. We have a Catholic, Buddhist, Christians, Hindu, Swaminarayan, and we get together at night, so we’ve come to know each other pretty well. Just about every night they come into my room and we eat snacks, chips or whatever, and we just start talking, you know, normal, I guess, girl talk—starting off with unimportant things, about, you know, things. And then there were a couple of times where we talked about really serious things.

One topic that comes up a lot is religion. And two or three girls down there don’t know what Buddhism is. They’ve heard of it and they know that, you know, this movie star, he’s Buddhist, and they’ve heard of the Dalai Lama, but they don’t what a real Buddhist is, what a Southeast Asian Buddhist is. And so we talk a lot about that and they ask me questions and I try to explain it to them, and I, in turn, ask them questions. You know, I ask my Hindu friend about her religion. She’s like, “We’re non-violent, we don’t eat meat,” and I say, “Well you know, our religion’s also nonviolent but we’re allowed to eat meat.” And so we’ve had huge debates about that and [we] pair off and one would defend me because we are all meat eaters, so it was like the whole of us against her.

It’s really interesting how much we can pull out of ourselves, just from sharing, how much we learn about our own religions. Because ever since then, I’ve come back and I’ve started to ask my father about digging deeper into my religion, talking to the monk a little bit more, reading some stuff on my own. So that’s been a really good way for me to learn about myself and I know that she had done the same thing and also the other girls. There’s an inter-varsity group there, which is like a Christian fellowship club, and she goes there and she’s like, “Oh, Ran, this is what we talked about today. It reminded me of something that we talked about the other night.” Or she’ll say, “We talked about something today and I thought about you and I really disagreed with it.” So it really makes you feel good when you hear that you’ve taught somebody something and that your words could affect them so much.

And we also talk about my history, you know, how it is that I got here, and they’re like, “I was born, I went to this school, I went to this school,” and that’s about it. They’re like, “Tell me about yourself.” I’m like, “Well, this is how I got here.”

But one night—I think that this is really something significant that happened with us—one of my friends there, she’s a great person, a very devout Christian, and we were talking about what it is to be American. It was me and my Indian friend and my Ethiopian friend, and we’re all, you know, we’re non-citizens, we’re just legal residents. So immediately we had this bond—we mainly agreed [about] everything. We’re like, “It’s kind of hard to call yourself American.” I label myself Cambodian, she labels herself Indian, Urgaba is Ethiopian.

And then my American friend was . . . she, I don’t know, there must have been something that she did not get. She must have felt that we were belittling her nationality, or whatever. And so she stormed out and she’s like, “I don’t get it.” At first the conversation was about problems within our communities, Julie (my Indian friend), me, and Urgaba. We were saying a lot of teenagers in our communities were losing not only their religious side, but also their cultural side. They were going around not only Americanizing in the way that they dressed, in the way that they talked, but even in the way they acted and thought, and that was a great concern for Julie and me and Urgaba. We’re like, “It’s not good to lose that, because you’re being a fake. You’re living a life of charades.”

And so my [American] friend comes in and says, “What’s wrong? Why can’t they call themselves American? You know, they live here, they eat and they drink, you know, speak and whatever, everything American. What is wrong with that?”

And we were trying to explain to her. We’re yelling and there’s a lot of tension in the room, and we’re just like, oh my gosh, it was supposed to be a simple conversation. She storms out and she goes, “I don’t know what it is that is wrong with me and those other white girls down the hall, you know, I don’t know what it is. What is wrong with us? What is wrong with being American?”

And I run up to her and I’m crying at this point, you know, it’s hysteria, and I’m like, “There’s nothing wrong, okay, there’s nothing wrong with being American. My point here, Julie’s point is that we’re not American, we can never be American.”

Why are you going to go around and lie that you’re American when it’s obvious to everyone that you’re not American, when most people will not accept that you’re American simply because [of] your physical appearance? And also, your parents are not Americans; they don’t call themselves Americans, because they know they’re not. They were raised a whole different way with a different culture with a different religion, you know, and they’ve shared all that with us. They’ve shared their language with us; they’ve shared their history with us. I’ve seen Cambodia through my parents’ eyes, through my grandmother’s eyes, through the monk’s eyes, through every other adult as they tell stories. I’m eating my country’s food, even though we mix American spices in it.

I remember telling her, “Would you want to go to Cambodia? And would you ever call yourself Cambodian?”

I don’t think she answered me. I was like, “It’s the same way with us, you know.”

“Think about you going to Cambodia and not ever telling your kids about Christmas. Think about going to Cambodia and celebrating Christmas, and not saying that you are American but that you’re Cambodian, but still having American ideals, still carrying through with American customs, and then calling it Cambodian. Wouldn’t you also be offended?”

And you know, she finally understood me. It was so emotional. I had never done anything like that. And I had never realized how important it was that I not call myself American; that I be identified as a Cambodian and be accepted as that; that my parents really knew that I valued that so much, all that my parents had shared with me.

BAL: I am sure it was very difficult.

RK: It was very difficult, very difficult.

BAL: But sometimes out of that we learn a lot.

RK: Yes, I learned a lot about myself that night and we hugged. It ended happily, you know. I think we’ve grown a little bit closer together because of that. Everybody says college is a place where you grow and learn and I think it’s just not in [the] classroom. I would never have gotten that out of a classroom.

BAL: Well, are you glad you went to college?

RK: I’m glad. I’m glad it turned out that way.

Tags

Barbara Lau

Barbara A. Lau is the Community Documentary Programs Director at the Center for Documentary Studies at Duke University. She recently served as guest curator at the Greensboro Historical Museum on the collaborative exhibition, From Cambodia to Greensboro: Tracing the Journeys of New North Carolinians.

Ran Kong

Ran Kong is a 2002 graduate of Salem College with a degree in Math and Economics. She is currently a distribution counselor with Amvescap Retirement in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. She recently served as a community scholar for the Greensboro Historical Museum exhibition, From Cambodia to Greensboro: Tracing the Journeys of New North Carolinians.