Tort Reform, Lone Star Style

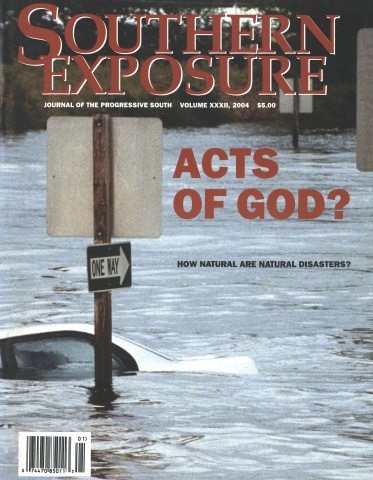

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 32, "Acts of God." Find more from that issue here.

On June 23, 1999, 24-year-old Juan Martinez and his uncle Jose Inez Rangel were hydro-testing a pipe at the Phillips Chemical plant in Pasadena, Texas. The pipe was about 10 feet from a reactor that manufactured plastic used in drinking cups, food containers, and medical equipment. At a crucial moment, plant operators opened the valves in the reactor out of sequence, sending an excess of a volatile chemical into the reactor, where it mixed with a catalyst to create a vapor cloud—and a fiery explosion. The blast coated Martinez and Rangel with 500-degree molten plastic. They were burned alive.

Martinez and Rangel were not the first workers to die at the Phillips plant. All told, 30 workers had been killed and hundreds severely wounded at the plant in the previous 11 years. The worst of the accidents happened in 1989, when an explosion killed 23 people at the plant. The chemical company paid out $40 million to compensate for the death of one of the victims.

In the lawsuit filed by Martinez’s widow, attorney John Eddie Williams would write, “No other serial killer in this state has been allowed to go unpunished and virtually unbridled for so long.”

A few months after he wrote that line, Williams was downtown taking the deposition of a worker from the plant. Williams looked out the window, he says, and saw smoke. Another explosion at the plant. And another worker dead—a man who had survived the 1989 blast. Seventy others were hurt, including four men who suffered third-degree burns over half their bodies. The explosion set off car alarms a mile away and closed nearby schools. “The guy being deposed would have been there,” says Williams.

All the pieces were in place for a big verdict—a statement from a jury of average citizens who would punish the company for its long record of death and indifference. After he presented the case to a mock jury, Williams says, the mock jurors were so horrified by the facts some of them began boycotting Phillips products.

But Phillips had little reason to worry. The company didn’t even bother to make a settlement offer to Martinez’s family. It knew it could come into court cushioned by a series of “tort-reform” measures championed by George W. Bush during his first term as governor of Texas. Among them was a cap on punitive damages, signed into law by Bush in 1995, which limited such awards to the greater of $200,000 or twice the economic damages, plus up to $750,000 for noneconomic damages such as pain and suffering.

Bush hailed the cap as way of reducing “frivolous” lawsuits. In order for the jury in the Martinez case to award punitive damages in excess of the cap, it would have to find that Phillips had “intentionally and knowingly” killed Martinez. In layman’s terms, the legalese meant that the aggrieved had to prove Phillips murdered Martinez, on purpose—a standard no civil case in Texas has ever met.

The jury, which was not told about the damage cap during the trial, found Phillips had been negligent and acted with malice in Martinez’s death. It awarded his widow, daughter, and parents $7.8 million in actual damages and $110 million in punitive damages—the equivalent of one month’s profits for the company. But state law would reduce the punitive damages to $3.2 million, making the entire award a fraction of one percent of Phillips’s annual profits.

For Texas trial lawyers, awards of that size give mega-corporations like Phillips the green light to make business and safety decision based on life-versus-profit calculations they term “Pinto math.” That’s the crude calculation used by the Ford Motor Company in the late 1960s and early 70s when it decided it was cheaper to let hundreds of people die each year than to spend about $5 per vehicle to prevent Pintos’ gas tanks from exploding in rear-end accidents. Without the threat of high punitive damages in wrongful death lawsuits, Texas oil and chemical companies like Phillips have little incentive to spend money to improve unsafe plants and pipelines. Certainly the government isn’t going to make an impact: federal officials cited Phillips for serious safety violations in the 1999 explosion that killed Martinez and Rangel, but fined the company just $140,000. Steven Daniels, a researcher with the American Bar Foundation, says, “Workers are just at the mercy now of their employers and the insurance companies.”

It’s a state of affairs whose genesis can be traced back to Bush’s long-shot run for governor of Texas in 1994. Bush won by running a relentlessly on-message campaign, harping on three or four key issues—among them his proposed limit on “junk lawsuits” by consumers and injured workers. In January 1995, just a few days after he took office, Bush met with members of a corporate-funded group, Citizens Against Lawsuit Abuse, at a salsa factory outside Austin. Declaring a legislative emergency on out-of-control lawsuits, Bush said, “Tort reform is the most constructive and positive and meaningful economic development plan Texas can adopt.” Calling the laws a “job creation package,” Bush went on to sign a series of measures that severely restricted citizens’ ability to seek civil justice.

As Bush sought his second term in the White House this fall, he and his backers gleefully attacked Democratic vice presidential nominee John Edwards as a parasitic trial lawyer. Bush is “trying to take some of the worst policy with the state of Texas and import it nationally,” said Austin plaintiff attorney Mark Perlmutter during the campaign.

The president’s reelection gives Republicans control of all three branches of the federal government and puts tort reformers in an ideal position to finally spread their agenda nationwide. Nine years into the transformation of the Lone Star State’s civil justice system, the experience of Texas is a preview of what the rest of the country might look like if corporate interests and their political allies succeed.

The Lions of Tort Reform

Whether they realize it or not, Americans are constantly hearing pitches for tort reform. A famous example is the case of the too-hot coffee from McDonald’s. In 1994, Stella Liebeck, an 80-year-old woman from New Mexico, won a $2.7 million jury award from McDonald’s for burns she suffered after spilling coffee purchased at one of the chain’s drive-through windows.

Jay Leno and other talk-show comedians had a blast, riffing on lawyers and hot beverages for monologue laughs. The punch lines, however, wouldn’t have worked too well with a more detailed set-up: Liebeck suffered third-degree burns on her private parts. She needed an eight-day hospital stay plus skin grafts to recover from the injury. At first, she had asked McDonalds to simply pay her medical bills, but the company refused. Documents uncovered during her lawsuit showed coffee buyers had filed more than 700 claims against McDonalds alleging that its coffee was too hot for human consumption. When the case went to trial, jurors did indeed award $2.7 million in punitive damages—to punish McDonalds for failing to remedy the problem that it knew was injuring lots of people. A judge subsequently slashed the award to $480,000—a detail that late-night comedians and tort reformers haven’t seen fit to mention, either.

Facts and nuance notwithstanding, the tort-reform lobby thrives by convincing the public that courthouses nationwide are passing out multimillion-dollar awards for spilled coffee every day. The real victims, tort reformers claim, are thousands of small businesses that are careening into bankruptcy as they try to defend themselves from frivolous claims. And in the early 1990s, they began a massive PR campaign insisting that Texas, with some of the best trial lawyers in the country, was a “plaintiffs’ paradise” and a magnet attracting people to the state to play the “lawsuit lottery.” Tort reformers asserted that the legal system needed an overhaul to make Texas more business-friendly. Tops on their wish list was a cap on punitive damages.

To push that agenda, Texas’s tort-reform pioneers coalesced under the banner of Texans for Lawsuit Reform (TLR), which opened for business in 1994, the year Bush ran for governor. At its kickoff, founder Richard Weekley proclaimed that lawsuit abuse was “the No. l threat to Texas’ economic future.” Like most other tort-reform offensives, TLR’s seized on a populist notion with adherents from coast to coast—namely, that lawyers are ruining America by bankrupting corporations with outrageous claims against honest companies. Yet some of TLR’s die-hard members hardly seem like innocent, abused entrepreneurs. A sampling:

• Enron CEO Ken Lay gave $25,000 in start-up funds for TLR. Lay had written to Bush in 1994 that if Texas didn’t do something about its “permissive” legal climate, Enron might just have to leave the state. Today, after more than 4,000 Enron employees have lost their jobs and their retirement funds invested in the company, Lay’s reasons for wanting legal immunity seem pretty obvious. But back then, Lay had more pedestrian concerns about its gas and energy operations. In 1994, one of the company’s methanol gas plants exploded in Pasadena, Texas, injuring several people working nearby. A neighboring chemical corporation sued Enron to block the plant from coming back on line, arguing that it had a long history of flagrant violations that were endangering workers.

• Richard Weekley, the driving force behind TLR, is a strip mall developer whose family owns David Weekley Homes, one of the nations’ largest homebuilding companies. David Weekley Homes is notorious in Texas for shoddy home construction and a host of worker safety violations. Dozens of homeowners with cracked and shifting foundations have attempted to file suit against the firm, alleging that their new homes began falling apart almost immediately after they moved in.

• James Leininger, founder of the Texas Public Policy Institute, which did the early polling to come up with the term “lawsuit abuse.” Leininger heads up Kinetic Concepts, a company that makes high-tech hospital beds that have prompted a rash of lawsuits from patients and nurses alleging that the rotating beds had dropped or crushed patients.

• Jim “Mattress Mac” Mclngvale, another TLR funder, is a furniture store owner who got sued after a 300-pound African lion kept at his Texas Flea Market mauled an eight-year-old girl and tore off part of her skull in 1987. The girl required extensive reconstructive surgery and faced the prospect of permanent brain damage. Her parents, who had no health insurance, sued Mclngvale for allowing the lion (which was owned by somebody else) on the premises.

The questionable business habits of many of Texas’ leading tort reformers is one reason their efforts had been mostly unsuccessful before 1994. But Bush changed things. Austin consumer attorney David Bragg says Bush was the friendly face TLR and the others needed to make lawsuit reform palatable to the public. “In the same way that Reagan legitimized the Christian right, Bush legitimized tort reform in Texas,” Bragg says.

Backing tort reformers, the governor endeared himself to a broad coalition of wealthy industry groups that had been attempting to push through limits on civil lawsuits nationally since the mid-1980s, particularly the tobacco industry. The year of Bush’s first gubernatorial campaign, the tobacco industry set aside $100,000 to underwrite a PR campaign in Texas heralding the epidemic of “lawsuit abuse” in the state. Tobacco money also helped create Citizens Against Lawsuit Abuse and provided $15,000 in seed money to TLR.

When Bush lined up on their side, that money started flowing his way. People and groups associated with tort reform donated more than $4 million to his statewide campaigns, more than any interest category other than oil and gas companies. As Bush’s longtime political advisor (and former tobacco industry consultant) Karl Rove explained to the Washington Post in 2000, once Bush declared war on “junk lawsuits,” “business groups flocked to us.”

The tort reform campaign also gave Bush a big stick with which to bash trial lawyers like John Eddie Williams, who plow their multi-million legal fees back into the Democratic party. Trial lawyers are, along with unions, one of the biggest sources of funding for the party.

One thing the measures promoted by Bush didn’t do was combat frivolous lawsuits. After all, it wasn’t the little “slip and fall” suits Enron was worried about. As Williams says, “Frivolous lawsuits by definition are worth nothing.” Besides, a state rule had been on the books for 15 years that allowed for sanctions against lawyers who file groundless lawsuits. “What they’ve done is outlaw big recoveries in good lawsuits,” says attorney Perlmutter.

And despite all the rhetoric, Texas never suffered from a “litigation explosion.” “There was never a time when Texas juries gave away lots of money all the time,” says Steven Daniels, a researcher at the American Bar Foundation who has studied the impact of Bush’s tort reforms on Texas. “Juries in Texas are almost always stingy.” Bragg, a former lawyer in the state attorney general’s consumer protection office, once did a survey of the awards granted under the state’s consumer protection act, which allowed defrauded consumers to recover triple damages from misbehaving businesses. It was hardly the major threat to the state’s economy that the tort reformers portrayed. Before the law was eviscerated in 1995 by Bush’s tort reforms, Bragg found that plaintiffs won their cases less than half the time in Dallas, and even when they did “win,” they rarely got any money. “But tort reformers decided there was a problem and mounted a major effort to change that law,” he says.

Under his campaign pledge of bipartisanship, Bush managed to persuade the Democratic lieutenant governor Bob Bullock to go along with a package of measures that severely limited citizens’ ability to win damages against corporations, doctors, hospitals, and insurance companies. The tort reformers couldn’t have been more pleased. Ralph Wayne, head of the Texas Civil Justice League and co-chair of Bush’s 2000 presidential campaign, says, “It is amazing the way someone like George Bush can make a difference. It was a marvelous year for us. Had it not been for George Bush and his persuasiveness we would not have been as successful.”

Those bipartisan “reforms” had their desired effect. Since Bush signed the bill in 1995, the number of personal injury suits filed in Texas has plummeted 40 percent, despite a rapid increase in the state’s population. Consumer lawsuits against sleazy car dealers, shoddy mobile home dealers, and other crooked businesses have become almost nonexistent, as have the lawyers who used to handle them. Daniels says lawyers simply can’t afford to take cases that don’t hold the possibility of punitive damages or awards for mental anguish because the actual amount of money involved in such cases is often so small. “Whether it was intended to or not, it may have the effect of cutting off access to the courts. If [lawyers] don’t want to take your case, you don’t get into court,” says Daniels. The behavior that spawned many of those suits in the past hasn’t disappeared. But without the lawsuits, the public simply doesn’t know about it.

Tort Reform Cure-All

The first thing President George Bush did this year when he went to meet with newly elected California Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger was declare his intention to discuss his campaign on frivolous lawsuits. “We need a little tort reform in this great state of California,” Bush announced. “Unfair lawsuits harm a lot of good and small businesses. There are too many large settlements that leave the plaintiffs with a small sum and the lawyers with a fortune. . . . Job creation will occur when we’ve got legal reforms.”

As president, Bush has continued to chat up tort reform at every opportunity. In fact, now that he’s passed most of his tax cuts and an education bill, tort reform often seems to be the administration’s only domestic policy initiative and its only answer to any of the nation’s ills. What’s the Bush plan for helping 44 million uninsured Americans? Medical malpractice “reform,” a bill in Congress that would impose Texas-style lawsuit restrictions on the rest of the country, capping punitive damages in lawsuits against drug companies, hospitals, nursing homes, and medical device manufacturers. The White House response to the 3 million people who lost jobs in the administration’s first three years? Class action reform, legislation that would federalize most class action lawsuits, essentially eliminating those pesky complaints against Wal-Mart in California alleging that the company stiffed its low-wage workers on earned overtime.

After listening to the rhetoric for the past eight years, at least one Republican small businessman back in Texas is no longer buying it. A few years ago, if you had asked Houston small business owner and Republican Walt Shofner whether he supported Bush and his war on lawsuits, he would have said yes. But in 2000, Shofner discovered the reality behind the PR campaign. His company designed software for insurance companies, and had recently beaten out a larger competitor on a bid to upgrade software at Prudential Life in New Jersey. Afterwards, the competitor, Computer Science Corp. (CSC), accused his firm of violating a nondisclosure contract and asked American Express and Prudential to cancel their contracts with Shofner, which they did. Shofner sued, arguing that CSC, a corporate giant with nearly $10 billion in revenues in 2000, was simply trying to squelch competition. The jury agreed and awarded Shofner $8 million in punitive damages.

But after the jury announced its verdict, the judge declared that he had to reduce the award to $200,000 because of the damage caps Bush signed in 1995. Shofner—as well as the jury—was shocked. Fred Kronz, one of the jurors in the case, says he couldn’t believe the news. Kronz says the jurors took their job seriously and spent a lot of time trying to come up with an adequate punishment for CSC, which they believed was clearly in the wrong. During the trial, everyone in the courtroom knew about the damage cap except the jurors, who only learned of it after they announced their verdict, making their deliberations seem like a charade, says Kronz.

The decision essentially killed Shofner’s business. He says, “CSC had no trouble paying me off. They got two or three million in revenue after I left [the other firms]. I got zapped for chump change by my competition. They have almost a monopoly on the software now.”

Shofner is now a vocal critic of lawsuit restrictions: “Tort reform assumes that all plaintiffs are crooks. But if a case gets far enough to get an award, that’s not frivolous. I was a Republican. I guess I still am. But I’ve seen the light. . . . Any small business person in Texas is at risk.”

Unlitigated, Unprotected

In fact, Texans may not become fully aware of what they’ve lost through the state’s tort reform until they need a lawyer. That’s what happened to Jacque Smith last year. In November 2003, Smith’s 85-year-old mother, an Alzheimer’s patient, was living at the Heritage Duvall Gardens nursing home in Austin. Late one night, a staffer entered Smith’s mother’s room and allegedly raped the elderly woman. Another employee witnessed the assault, but apparently didn’t bother to report it to anyone and went home after his shift finished. Smith only learned about the assault because the witness mentioned it to someone at the home during an unrelated conversation later the next day. After her mother was examined at a hospital, the assailant was arrested and charged with aggravated sexual assault.

Smith then consulted a lawyer about filing suit against the nursing home for poorly supervising its employees. In the past, such a suit might have garnered a multi-million-dollar settlement or jury verdict for the victim. Texas has some of the worst nursing homes in the country. A 2002 study by the special investigations division of the U.S. House Committee on Government Reform found 40 percent of Texas nursing homes committed violations of federal regulations that caused harm to nursing home residents or placed them at risk of death or serious injury. More than 90 percent did not meet federal staffing standards. The poor conditions of Texas nursing homes led to a cottage industry in the legal profession, whose lawsuits posed much larger threats than any state sanctions.

A Harvard University study found that nearly nine out of ten nursing home plaintiffs received compensation, a success rate that the study deemed “off the scale” in personal injury litigation, and a sign that the negligence as well as the severity of injuries in the cases was clear-cut. Rather than pledge to clean up its act, the nursing home industry lobbied hard for the passage of legislation that would put the lawyers out of business. The state passed the nursing homes’ favored medical malpractice bill in September 2003, capping pain and suffering awards at $250,000.

The new law has produced the results desired by its backers. When Smith looked for an attorney, she discovered her first hurdle might be simply finding one willing to take the case. The first attorney she called declined, as few lawyers in Texas will now handle such a complaint. Then she contacted Bragg, who explained to her that the most her mother could win would be $250,000, because there were no economic damages involved. Smith’s mother, after all, didn’t have a job to lose and she didn’t incur significant medical bills. After taxes and legal fees, she would receive at most $100,000. That would make her ineligible for Medicaid, meaning the money would end up being funneled back into the nursing home industry that failed her in the first place.

As a result, Smith says she’s unsure whether she will pursue legal action because she worries that any money that might result from it would not be used to improve the quality of her mother’s life. But she is frustrated by the prospect of simply dropping the case. “It feels like somebody should be held accountable,” she says.

According to a study by the Dallas Morning News, since the bill’s passage medical malpractice lawsuits in Texas have fallen off by 80 percent. Ironically, in giving advice to citizens on how to choose a nursing home, the Texas Attorney General’s office suggests using the number of lawsuits against a home as a good gauge of quality. Its web site counsels, “A nursing home that gets sued frequently should not be your first choice.” How the public will make these choices in the future? The web site doesn’t say.

Tags

Stephanie Mencimer

Stephanie Mencimer was a finalist for a National Magazine Award for her reporting in The Washington Monthly on the battle over medical malpractice and tort reform. She is the author of “The Price of Confession, ” which appeared in the Winter 2003/2004 edition of Southern Exposure. Funding for this story was provided by the Alicia Patterson Foundation and the Fund for Investigative Journalism. (2004)