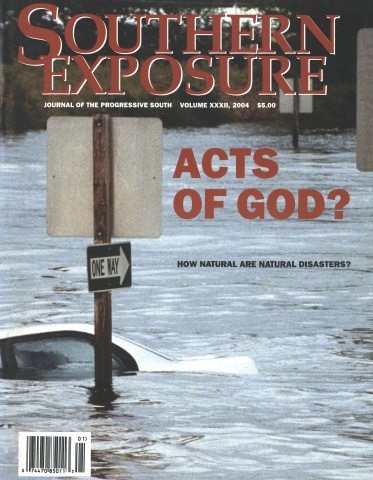

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 32, "Acts of God." Find more from that issue here.

When three massive earthquakes occurred along Missouri’s New Madrid fault in 1811 and early 1812—unrivaled in the continental United States in severity and scope—they were interpreted by many as a sign of God’s power. They also seem to have inspired those who had somehow lost their faith in God to return to the fold. James Lai Penick notes that in the Midwestern and Southern states, where the quakes were felt most forcefully, membership in the Methodist church increased from 30,741 in 1811 to 45,983 in 1812. Methodist membership rose by only 1 percent in the rest of the country. Many citizens of the young republic, explains Penick, sought moral lessons in natural calamities, seeing them as signs and portents.

Today, if one believes the pollsters, only about one-fifth of Americans derive such moral lessons from extremes of nature. What the remaining population thinks on the matter is unclear. Many no doubt see natural disasters as simple acts of nature, a view that reflects the increasing secularization of 20th and 2 lst-century American society. To most people these events probably lack any clear moral imperative or lesson. Natural calamity has become, if you will, demoralized, except of course in the sharply confined circles of the superfaithful.

The demoralization of calamity has resulted in a new set of rhetorical opportunities for those in power. Once, the idea of invoking God in response to calamity was a strategy for eliciting moral responsibility. In the 20th and 21st centuries, however, calling out God’s name amounted to an abdication of moral reason. With the religiously inclined less disposed than ever to take acts of God seriously, the opportunity has arisen over the last century for some public officials to employ God-fearing language as a way—thinly veiled though it may be—of denying their own culpability for calamity. In this sense the “act of God” concept has become little more than a convenient evasion.

We can see the start of this shift in post-Reconstruction South Carolina, part of a nascent New South in which boosters and entrepreneurs were trying to revise traditional religious outlooks in order to build a new business culture—when nature rudely interrupted.

Disaster-Struck

It is hard to find a place more disaster-struck than Charleston, S.C. Founded in 1870 on a narrow peninsula at the confluence of the Ashley and Cooper rivers, Charleston remained disaster-free in its early years. Then in 1686 a hurricane, “wonderfully horrid and destructive,” wreaked havoc on the city, which is barely 10 feet above sea level. Smallpox erupted in 1697, killing “200 or 300 persons.” The following year an earthquake rocked the town, causing a fire to break out that destroyed one-third of the settlement. In 1699, yellow fever surfaced, followed by a hurricane that ripped apart wharves and flooded streets.

In 1713, another hurricane swept through, causing extensive flooding and washing ships ashore. The year 1728 brought drought, yellow fever (“multitudes” died), and yet another hurricane, which sent residents scurrying to the top floors of their homes. A fire broke out in 1740, gutting some 300 houses and reducing the merchant William Pinckney and his company, the Friendly Society for the Mutual Insuring of Homes against Fire at Charles Town, to bankruptcy. One of the fiercest hurricanes in Charleston’s entire history blew ashore in September 1752, killing more than 15 people and at one point inundating the city to a depth of nine feet.

Storms struck again in 1783, 1787 (drowning 23 people), 1792, 1797, and 1800. In 1804, a hurricane swept up the coast of South Carolina, putting “a great part of Charleston under water . . . in some places breast deep.” Seven years later came a tropical cyclone combined with a tornado. Two years after that a hurricane took at least 15 lives and destroyed a newly built bridge over the Ashley River. A “violent tempest” struck the city in 1822, blowing down houses and drowning eight people. In March 1838, a fire started in a fruit store near the intersection of Beresford and King streets, obliterating an estimated $3 million worth of buildings. The year 1854 brought another hurricane, followed by yellow fever, which killed 600.

Then came the Civil War. In 1861, while Gen. Robert E. Lee inspected the city’s defenses, a fire roared through town, burning more than 500 acres. Damage was estimated at between $5 million and $8 million. There were hurricanes in 1874, 1881, and 1885, the last a storm so severe that it caused the deaths of 21 people and destroyed or damaged 90 percent of Charleston’s private homes. So many trees feel that it took 10,000 cartloads to haul the mess away.

Yet since virtually all these disasters were either weather-, disease-, or war-related, the events of 1886 proved surprising to many. Several minor earthquakes—largely unnoticed—occurred in the city that summer. But on August 31, near 10 p.m. on a humid night, what began as a barely perceptible tremor became a monstrous earth-shaking roar that lasted for more than half a minute. The earthquake had two epicenters: one near Rantowles, roughly 13 miles west of Charleston, and one in Woodstock, 16 miles northwest of the city. The magnitude (M) of the earthquake was later estimated to be 7.0—the largest seismic event in recorded history on the eastern seaboard.* Ten severe aftershocks rattled the Charleston area over the next month. In all, a huge expanse, equivalent to two million square miles, experienced the disturbance. Tremors were felt in such far-flung places as Boston, Milwaukee, Cuba, and even Bermuda, 1,000 miles away.

Because of the time of night at which the earthquake struck, no major loss of life occurred. A few died as buildings collapsed around them, but the vast majority of deaths happened outside, where people were struck by flying debris. Mrs. Jacob Middleton lost her life when the wall of the police station on Meeting Street collapsed on her. Ainsley Robson was killed by a falling piazza on Coming Street. In all, as many as 110 Charlestonians died.

Property losses, however, proved even more devastating. Most of the damage resulted from the main quake in August, which destroyed more than 12,000 chimneys and caused a total of $6 million in repair work. Twenty-five percent of the total value of all buildings in the city vanished in less than a minute. Destruction was especially bad near the intersection of Broad and Meeting streets, the very heart of Charleston. One of the city’s most famous and beloved structures, St. Michael’s Church, nearly toppled; its enormous portico had been ripped from the body of the church. The city hall suffered bad cracks in two of its walls. The main police station had been turned into a Greek ruin, the roof and entablature caving in around its huge Doric columns. Nearby, the Greek Revival Hibernian Hall lay in a steep pile of rubble. The devastation was so spectacular that visitors descended on Charleston from all over the East Coast. And they were not disappointed. Some tourists, noted the Charleston News and Courier, were so “forcibly impressed” with what they saw that they elected to take an early train back home.

The monstrous destruction created an incredible demand for labor, driving up wages. One report issued just a few days after the calamity noted that “there was a pressing need for laborers, a fact which nobody appreciated more than the laborers themselves. . . . Colored men . . . wanted 50 cents an hour for their services at odd jobs.”

In truth, the earthquake could not have come at a worse time for the city. Charleston had risen to power and commercial dominance in the 18th and 19th centuries as cotton and rice plantations expanded through the hinterlands. An excellent system of navigable rivers penetrating the interior allowed crops to enter Charleston after which they were shipped out of the city’s well-protected harbor. But in the years after the Civil War, the port’s commercial prospects began to wane. In the 1880s, railroads crisscrossed the region, bringing crops overland to markets in the north and eclipsing Charleston altogether. When the quake struck, the city’s commercial empire—once dominant over the stretch from Savannah to Wilmington, North Carolina—was badly damaged.

“They Had the Assurance of Numbers”

In the eyes of the white business class, the only thing more shocking than the earthquake was the way Charleston’s blacks responded to it. According to the News and Courier, two days after the quake, as the sun went down on Washington Square—itself a ragtag collection of boards, canvases, old carpets, and anything else that could serve as shelter—a large group of “half-grown negroes, men and women, began to play base ball, and for a time took complete possession of the place, rushing about indiscriminately over every one and filling the air with shouts and curses.”

Although many of the blacks who filled the square were, as one press report noted, “respectable people,” a contingent of poorer blacks from the “lowest classes” and “slums” seemingly did their best to stoke the anxieties of Charleston’s whites. The day following the earthquake two black men “were preaching and exciting the colored women to frenzy. . . . They had the assurance of numbers and refused to desist, or to conduct their exercises in moderation.” Within several more days, the News and Courier reported, the square had “been completely occupied by the colored people, who seem to enjoy camping out as they would a picnic. . . . At night the religious orgies of the colored people were so boisterous and maddening that many of the white people were unable to stand it and were driven off, preferring to risk their lives in their ruined houses than to undergoing the tortures to which they were subjected by these exercises.”

The historian Don Doyle describes late 19th-century Charleston as a “privileged white minority [holding] onto its precarious position amid a sea of impoverished blacks.” This situation became even more pronounced after the Civil War, as freedmen—mostly poor agricultural workers from the Sea Islands—flowed into the city in enormous numbers. Between 1860 and 1880, Charleston’s black population swelled from roughly 16,000 to more than 25,000. In 1880, blacks made up more than half the city’s population. “We very rarely go out, the streets are so niggery and Yankees so numerous,” wrote one white woman not long after the war ended.

The Fourth of July was especially galling to whites, who stayed home while blacks dominated the festivities. Such behavior was not an overt act of resistance the way a riot or strike would have been; it might be construed all the same as an act of symbolic opposition. In this sense, the dramatic intervention of nature in 1886 allowed blacks to appropriate public space and to disrupt everyday social norms and behavioral codes.

In part, such transgressive behavior flowed from the blacks’ interpretation of the earthquake calamity as an act of God. Gabriel Manigault, a museum curator and son of a wealthy rice planter, wrote that the city’s black citizens were more unnerved by the quake than were white people such as himself, who understood it as resulting from natural forces. Blacks, he asserted, “were absorbed in prayer during the continuance of the minor shocks, under the belief that this was a punishment visited upon them for their sins.” A white bookkeeper named J.B. Gladsden complained that the religious meetings of “the ignorant coloured people, as they huddled together in their terror, were among the most annoying circumstances we had to contend with.”

At least one bona fide black account of the disaster does exist. Norman Bascom Sterrett, a minister in nearby Summerville, South Carolina, close to one of the earthquake’s epicenters, admitted being quite terrified. “I have no apology to make for my fright,” he wrote, “for every one present was frightened, and I believe I am frightened yet.” Sterrett also noted, however, that in Summerville at least, both blacks and whites had assembled in the wake of the disaster, “mingling their voices together in supplicating the Great Ruler of all events to spare us from such a horrible death, which, without his interposition, seemed inevitable.”

Why were whites so troubled by what they saw as the black reaction? How exactly should they have behaved during the calamity? The white Episcopal minister Anthony Toomer Porter, of the Church of the Holy Communion, offered an answer. In place of frenzied religious activity and living outdoors, Porter instead prescribed bed rest, so that one would be fresh for work the next day. “What your people want, as do our people, is absolute rest after the excitement incident to the unusual scenes they have witnessed—I mean rest at night—that they may work steadily in the day.” Undoubtedly, the earthquake had empowered blacks, however briefly, to escape from the normal routines of wage labor, something that struck at the heart of white economic interests in the Jim Crow South.

Although Porter agreed that God was behind all things that happened on earth, he thought it wrong to see the calamity as a punishment for human wickedness. The disaster was instead simply the result of Charleston’s particular location—the product, in short, of amoral nature. Porter’s colleague, the Rev. Robert Wilson of St. Luke’s Episcopal Church, also criticized those who understood the disaster as an act of God. As he put it, “the man who calls this a ‘visitation of God’s wrath for sin’ is a fanatic who ought to be silenced.” Porter and Wilson thus became spokesmen for the official city position, an unsurprising development given that the Episcopal church was the principal religious affiliation of Charleston’s commercial elite.

Mayor William Courtenay also argued for the quelling of religious frenzy. A former cotton farmer and conservative Democrat elected in 1879, Courtenay sought to modernize the city by putting its finances in order, improving public services, and helping to impose the work discipline needed to create the proper business climate. Immediately after the earthquake, he observed, “our colored population, whose very natures are emotional,” resorted to song and prayer. But the best route to recovery, he explained, was to get back to work. The future of the city “is based on work, not idleness, and I call upon every one to seek work in any and every way possible.”

Courtenay also advised citizens to return to their homes: “What our people want is relief, immediate, permanent relief from the terrible nervous strain to which they have been suddenly subjected, and which will certainly continue in the tent life which many are leading in the streets and public squares.” It was but one step from living in the streets to perhaps leaving town altogether, a point that must have severely troubled Courtenay and the rest of the white business class, who were certainly cognizant of the fact that mobility was a central form of black working-class protest.

Under the leadership of editor Francis Dawson, the influential News and Courier had long sought to spur Charlestonians to shed their plantation heritage and preindustrial ways and move forward to a new economic order—the New South—with a new understanding of work discipline and a new vision of calamity as well. According to Dawson’s paper, seeing the earthquake as a form of divine punishment was “entirely opposed to anything like helpful labor.” The paper continued:

“People who spend most of their nights shouting and exhorting at ‘experience’ meetings have little strength and no inclination for work next day. To assist the community in trouble by taking up a daily routine of honest industry seems useless to them, while they are constantly looking out for the devil in his own proper person, horns, hooves, and all.”

It was better instead to interpret the calamity as simply an impersonal natural event, devoid of any overriding moral meaning. That way one could stay calm, get plenty of rest, and be ready for work the next day. “The work, we are told, is to pray, and this together with courage, duty, and discipline, form better watch-words than ‘Down in the dust;’ ‘It is the wrath of God!’ ‘A visitation.’”

A Little Sugar Please

Back in the 1820s, city authorities in Charleston had a bright idea. They installed a treadmill in the city’s workhouse where slaves were sent for “a little sugar,” meaning a whipping. In the “Sugar House,” black slaves had their arms strung up above them and were forced to keep up with the treadmill while being flogged. The idea was to make slaves suffer pains worse than those related to their labor, so that work and docility would seem preferable to life on the mill. This practice of using suffering as a tool to rein in blacks did not disappear with the end of the slave system and the rise of the free market in labor. It reared its head again in the relief campaign that the Charleston business class organized to get the working poor back on the job after the earthquake. Under capitalism, explains historian Wilbert Jenkins, Charleston’s “blacks were free to work, if they could find work, and free to starve if they could not. The whip of slavery was being replaced with the lash of hunger in an economy that could provide few subsistence-level jobs.”

Since the very idea of relief aid threatened the maintenance of work-discipline, many city leaders would have preferred not to raise and dispense such funds. Soliciting outside aid was especially problematic because it could be construed as a sign of weakness and thereby serve to undermine the city’s self-reliant image. Indeed, just the year before, when a powerful hurricane struck Charleston and caused perhaps $2 million in damages, Mayor Courtenay declined offers of outside assistance from other cities (a common practice in the years before the federal government became a major provider of relief). Dawson’s News and Courier supported Courtenay in this decision: words of “discouragement and dismay,” wrote the paper, would only have convinced “the commercial public . . . that Charleston was so injured as to be incapable of handling properly the business which was wont to be confided to her.” The paper concluded that “there must always be some suffering in a city of about 60,000 inhabitants.”

The economic impact of the 1886 earthquake, on the other hand, was far too devastating for Charleston’s business class to consider turning away outside financial support. But very close attention was paid to the effect on work-discipline of distributing rations and other forms of aid. Charity was not “intended for those who can work,” warned one relief official. “The [relief] committee wish it distinctly understood that none but the actually needy and those incapable of self-support need apply for aid, as there is abundance of work, at extra pay, to be gotten in Charleston.”

In a calculating move, Courtenay and Dawson, who dominated the relief effort, cut off subsistence relief just a month after the disaster. Courtenay explained that food relief was ended because of “great abuses” that developed as black farm workers came from far and wide, “to the great neglect of their crops, in order to get ‘free rations’.” A month after subsistence aid ended, the black pastor W.H. Heard reported still plenty of misery in the city, at least among his own congregants: “The condition of the people beggars description—no fire, save a little out doors, poorly clad and living in damp districts. The death rate is nearly double.”

Not content simply to withhold immediate aid, those managing the relief effort also saw to it that only the most persistent would receive funds to rebuild their homes. Anyone seeking reconstruction money, for example, was required to complete a daunting three-page application. “If every blank in the form is not filled up, the application will be returned,” would-be applicants were warned. The complexity of the application drew criticism from around the country. In a letter to the editor appearing in the New York Herald, one observer noted that “in the history of the world there never has been a more prohibitory system of ‘red tape’ imposed upon applying beneficiaries where a public charity fund was to be disbursed.” To make matters worse, more than four-fifths of black South Carolinians age 21 and older were unable to write.

In the end, the bulk of the burden of repairing buildings fell on property owners themselves. Only 2,200 of the close to 8,000 buildings in need of repair received funds from the city’s relief committee.

If Charleston’s leaders were unwilling to share their resources with the city’s poor, it was because such stinginess fit in with their interpretation of calamity. For the business class, the earthquake disaster constituted not an act of God, but a natural event and an obstacle to economic progress. The concept of an act of God implied that something was wrong, that people had sinned and must now pay for their errors. But the idea of natural disaster may have implicitly suggested the reverse, that the prevailing system of social and economic relations was functioning just fine. No elaborate morality tales need be proffered in the aftermath of such an event, as had long been the case in the past. Instead, people were to remain calm and disciplined as they restored things to normal—effectively legitimating the prevailing social system in the process. In this view, natural disasters were not worthy of any deep or considered thought. They simply happened from time to time. Thinking about their larger meaning could only help to distract people from the task of restoring normality—with all its assumptions about the need to maximize the value of both human and natural resources. Ultimately, a view of the seismic shock as only a natural disaster amounted to little more than a thinly veiled attempt to return the poor back to the city’s economic treadmill.

It Couldn’t Happen Here . . . Could It?

Given the great lengths to which Charleston’s leaders went to keep the earthquake disaster from interfering with the city’s commercial agenda, one imagines that they would not have been to disturbed to learn that 100 years later it had been all but forgotten. In the century after the quake, construction went on, and builders for the most part were utterly unconscious of the seismic hazard, functionally reproducing the same fatalism inherent in the act of God interpretation.

As late as 1983, according to civil engineers James Nau and Ajaya Gupta, the majority of the city’s buildings and facilities were “still without adequate seismic resistance.” In the early 1980s, metropolitan Los Angeles had some 12,000 buildings lacking in seismic adequacy; yet Charleston, despite being a much smaller city, had even more such compromised structures. “With the exception of building inspectors and structural engineers,” a report by the U.S. Geological Survey observed, “few of the respondents currently incorporate awareness of an earthquake hazard into their decisions.” Although nearly all those questioned were familiar with the 1886 disaster, few “took seriously the possibility of an occurrence of a future earthquake” of a similar magnitude.

The earthquake is thus seen as a unique event, with little meaning beyond its value as a quaint episode in the city’s past, a fact mentioned on horse-and-buggy tours otherwise consigned to the dustbin of history. Perhaps that is why it took Charleston until 1981 to pass an amendment to the building code requiring adequate seismic design.

To the extent that the 1886 quake was seen as a problem, it was understood for nearly a century to be Charleston’s problem alone. Throughout the East, very little attention has been paid, until very recently, to the threat of earthquakes. John Lyons, the director of the engineering laboratory at the National Bureau of Standards, observed as late as 1984 that despite the lack of detailed surveys “it is fair to say that seismic design is simply not practiced” in the eastern and, for that matter, even central United States. To be sure, the East is much less seismically active overall than the West. But although the probability of an earthquake is lower, the risk of a major seismic calamity is actually very high. This is because seismic energy tends to travel greater distances in the East. Compare, for instance, the 1886 earthquake with the 1971 San Fernando quake. Both were of roughly the same magnitude. But the Charleston quake made itself felt over an area 10 times as large, cracking walls in places as far away as Harlem.

Why have earthquakes not been seen as a problem in the East? In part, the lack of awareness stems from the failure to locate the geological formation responsible for the Charleston disaster. Unlike California, where the source of seismic activity is routinely identified—correctly or not—with the famed San Andreas fault, no such structure has been discovered in the South. As late as the early 1960s, scarcely more was known about the 1886 quake from a scientific perspective than at the time it happened. Even in the 1970s, the dominant scientific view of the disaster held that unique conditions existed at Charleston, localizing the earthquake problem. Hence in its decisions regarding where to locate nuclear reactors, the Atomic Energy Commission ruled that while design requirements in the Charleston area were to be in keeping with the risk of another 1886 earthquake, along the rest of the eastern seaboard the seismic history of this Southern city would not influence the blueprints one bit. The significance of the 1886 disaster has thus been minimized—interpreted as a singular event of only localized importance.

The Charleston calamity, starved of its meaning for future generations, is little more than a footnote in the annals of disaster, a very poor cousin to the famed San Francisco earthquake 20 years later. Cordoned off as a unique—shall we say freak—event, the Charleston experience has been ignored by developers and planners as they have forged ahead in the building of such projects as Manhattan’s Battery Park City, which was constructed on a quake-prone landfill. Yet as the most deadly and destructive quake ever to strike the East, the 1886 Charleston disaster should stand as a symbol of what the denial of seismic risk might lead to, a reminder that earthquakes are not a concern for Californians alone, a warning of just how important it is that we examine the geography of risk and how it is produced and, most of all, a prediction that the coming eastern earthquake calamity—whenever it occurs—will not be an act of God.

* The Richter scale for measuring earthquake magnitude was developed in 1935. However, in the 1980s seismologists turned instead to a better way of measuring the size of earthquakes called seismic moment. Moment magnitude (M) takes into account area, fault offset, and the rigidity of the rupturing rocks. Unless indicated otherwise, all figures for earthquakes are based on the moment magnitude scale.

Tags

Ted Steinberg

Ted Steinberg is a professor of history and law at Case Western Reserve University and the author of Acts of God: The Unnatural History of Natural Disaster in America, from which this essay is adapted. (2004)