This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 32, "Acts of God." Find more from that issue here.

Taking their cue from the black civil rights movement, the AFL-CIO and immigrant groups joined to recruit hundreds of members last fall to traverse the country by bus in an attempt to bring attention to the plight of U.S. immigrants.

And it may have worked. The Immigrant Workers’ Freedom Rides, modeled after the freedom rides of 1961, catapulted immigration issues to the forefront of the national discourse—every presidential candidate this year included a stance in his or her platform.

More importantly, the rides illuminated the struggle of the U.S. immigrant population, a group on the fringes grappling to attain worker protections and civil rights. Immigrants may have found their answer by fusing with the black and labor movements, revitalizing those struggles in spirit and supporters as well.

U.S. Congressman John Lewis (D-Ga.) was still a college student when on May 20, 1961, he and 20 other black and white freedom riders arrived in Montgomery, Ala. The mob of whites who met them beat a nonviolent Lewis into unconsciousness. The event drew media attention that forced the nation to face its deeply ingrained racism and helped spark the civil rights movement.

Some have said the immigrant movement has essentially the same goal as did the ’61 freedom riders. Those riders challenged segregation on interstate buses through the South; immigrants seek to become more fully integrated participants in U.S. life. Recognized as key components of that integration, the immigrant freedom riders called for legislators to guarantee a path to citizenship, expedited family reunification, workers’ rights, and civil liberties for all.

Lewis draws parallels as well, saying last fall’s freedom rides addressed the fact that a segment of the population is treated differently “because they are immigrants.”

In 1961, he adds, part of the method to change the system of overt racial discrimination was to dramatize the need to do so.

Nine hundred immigrant riders bussed across 20,000 miles of highway, spanning the country on nine routes. The ride ended with a mass rally in New York with tens of thousands of supporters. Along the way, the travelers lobbied legislators in Washington, D.C., in meetings coordinated by National Council of La Raza, a national Latino advocacy organization. NCLR was one of numerous immigrant and racial and ethnic advocacy groups that joined the effort.

There are 31.1 million people living in the United States who were born abroad, according to the 2000 census. It is estimated that between seven and ten million of them are undocumented. Some are recent arrivals, while others have resided here the majority of their lives.

By the time the immigrant ride routes merged in Washington, D.C., “We Are One,” had emerged as the dominant rallying call. It represented the solidarity shared by the three movements and celebrated the unity among riders of great diversity.

Like the national immigrant population, 52 percent of which is Latino, the largest group of riders was Hispanic. Many riders also hailed from countries throughout Africa, Asia, and the Caribbean. One of the buses that began in Seattle claimed passengers that trace their roots back to 22 countries.

To show his support, Lewis welcomed the immigrant riders in Washington, D.C., and became a freedom rider again, boarding a bus to New York.

“Some of the issues, some of the concerns, some of the same problems still exist today,” he says.

“We must confront those problems head on.”

To do so, many immigrants are turning to organized labor, says Maria Elena Durazo, a California union president and national director of the Immigrant Workers Freedom Rides.

In turn, she notes, some labor heads are reaching out to immigrants.

“There’s not a single industry where there aren’t immigrant workers,” says Durazo, and some unions are starting to see this.

According to Maria Jimenez, a longtime community activist hired by the AFL-CIO to help recruit immigrant riders, it’s in the interest of unions to organize immigrants because they are the workforce.

“It’s a matter of their own survival,” she says, noting a decline in union membership in recent years.

The AFL-CIO currently reports about 13 million members, compared to 14 million in 1990. Of the overall civilian workforce, it finds 13 percent of workers are unionized, compared to a peak at 32 percent in 1958.

Immigrants make up 11 percent of U.S. residents, 14 percent of the workforce and 20 percent of all low-wage workers, according to the Urban Institute’s report on the 2002 Current Population Survey.

The freedom riders embodied the developing relationship, as the majority of them were immigrants, union laborers, or both.

The goal was to show the country the abuses immigrants face, says Durazo. Because they lack the same rights as citizens, workplace abuses hit especially hard among immigrants, particularly the undocumented, according to Durazo.

“I don’t think people realize what horrible things are going on every day.”

The riders had a multitude of motivations and experiences propelling them to the buses.

Irene, a worker in a poultry factory in Texas, complained the constant grueling work once caused her right forearm to swell so badly it pinched her nerve, leaving her arm paralyzed for nearly a week.

“I’ve seen a lot of people get hurt,” she says. “They’ll pay your medical expenses and let you come back, but they’ll find a way to get rid of you—if they think you’re ‘accident prone.’”

After six years with the company, Irene makes $8 an hour.

Another rider, Nancy, came to the United States when she was four years old, but endures the worry that she and her family could be deported to a country that is foreign to her.

“Now I am in the 12th grade. It’s not fair that after being here so many years we are not citizens,” she says.

Attending a rally in New Orleans, a group of about 20 men from India explained that they each paid $10,000 to a headhunter who promised them a green card and a job. Now they are stuck in apartments without food, pay, or employment.

Many riders considered telling their stories a risk and boarding the media-magnet freedom buses an act of defiance. Although the threat of violence was low when compared to 1961, the immigrant riders knew they faced detention and deportation. They could be sent back to countries they had left due to violent wars, dire economies, or because they hoped they could provide more for themselves and their families in the United States.

Sick of being “second-class citizens,” a term borrowed from the black movement, many riders said they felt empowered once they boarded the buses. At 103 cities, they rallied with other immigrants, union members, and supporters, coming out of what some call life in the shadows to demand rights.

There is some debate surrounding what economic and societal rights immigrants actually deserve. University of Southern California law professor Erwin Chemerinsky says that the fact that many immigrants lack citizenship, while blacks did not, creates different legal issues.

“With regard to immigrants, the question is what should their rights be,” he says.

Lewis believes that lack of citizenship is a moot point. “There are basic rights of all humankind and no government—state or federal—should be able to deny people those basic God-given rights,” he says.

Despite Lewis’ argument, many legislators continue to question the rights of immigrants. In states including Colorado and Arizona, voter-led initiatives and bills have been introduced that deny immigrants social and medical services. In California, one of Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger’s first moves was to repeal a law that would have allowed undocumented immigrants driver’s licenses. In states including Maryland, Minnesota and New Mexico, taxpayers and lawmakers debate whether undocumented students should pay in-state tuition at colleges and universities.

Durazo urges legislators to focus on the problems immigrants face, rather than policy debates.

“There are people working in hotels, as janitors, in the fields and they work hard every day and they’ve been here for 15 years . . . and they’re paying taxes and yet they don’t have any rights. Any day they could be deported.”

The nine-day immigrant ride route that began in Houston, Texas, visited the places freedom buses had stopped in ’61 as well as many of the struggle’s Southern landmarks. In Jackson, Miss., where freedom riders were jailed four decades ago, the 80 immigrant riders were invited to the capitol building to share dinner with Robert Clark, the first black elected to the state legislature. In Selma, Ala., riders marched across the Edmund Pettus Bridge, where state and local police attacked black marchers in 1965 in what came to be known as Bloody Sunday.

At these and other stops riders were welcomed and supported by primarily black groups of leaders, legislators and union workers. Throughout the South, riders were often provided home-cooked meals and fellowship at churches and union halls.

“We need to turn to each other, not on each other. Black and tan go good together,” said Rev. Joseph Lowery addressing riders in a church where Martin Luther King Jr. had been pastor, Dexter Avenue King Memorial Baptist Church in Atlanta, Ga. With King, Lowery cofounded the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, an organization instrumental to the black movement.

Many immigrant riders said they were inspired by the stories they heard of what blacks endured to progress. For Martha Olvera, a wreath-laying ceremony at King’s grave in Atlanta, proved overwhelmingly emotional. While the group sang We Shall Overcome and other traditionally black spirituals, she burst into tears.

Olvera has lived in Houston since 1974 when she moved from Mexico. In 2001, her brother-in-law, Serafin Olvera, was one of a group of men arrested when immigration officials raided a house in Bryan, Texas. Serafin’s neck was broken during the raid, but he did not receive medical attention until seven hours later. The rest of the men arrested were deported the same day.

Serafin would remain hospitalized for nearly a year, until he died.

Olvera says abuses by border patrol are commonplace in Bryan. She helped the U.S. Department of Justice find deported witnesses and build a case against the agents involved. Three were found guilty of civil rights violations two years later, one for using excessive force and all three for deliberate indifference to Serafin’s medical needs.

Standing at King’s grave, sunlight shimmering on the pool that surrounds it, Olvera thought of her brother-in-law. When she began crying, two women comforted her. They each hooked an arm through Olvera’s. One woman was black, the other was white.

“If this man, years ago, had not done all he did, my family would not have found justice,” Olvera says.

“The path he left open, we continue.”

Many immigrant advocates say that King would have supported the immigrant movement, including Lewis who, as national chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, often worked with King and the SCLC.

On more than one occasion, King explained what he called the interrelated structure of reality. All groups and people are bound together, he reasoned, and therefore justice for one helps create progress for all.

“One day we shall win freedom, but not only for ourselves. We shall so appeal to your heart and conscience that we shall win you in the process, and our victory will be a double victory,” King said.

According to Durazo, “The civil rights movement strengthened this country. It wasn’t about a particular group of people, everybody benefited.”

She points out that women, all people of color, and immigrants progressed because of the black struggle.

Throughout the Southern ride, union members rallied with riders. In particular, member of the Laborers union, SEIU, UFCW, UNITE and HERE (before the latter two merged) welcomed riders in large groups, often providing a meal.

“The United Farm Workers was probably the first union that took a strong position to support the rights of immigrant workers to organize” and it did so before 1970, says Bill Chandler, president of the Mississippi Immigrant Rights Association and Houston ride coordinator.

Chandler began organizing in the ’60s in California where he met Cesar Chavez, whom he followed to work with the UFW.

Just as unions in the South once discriminated against blacks, according to Chandler there continues to be discrimination towards immigrants by labor unions. This may stem in part from the youth of the relationship in some Southern states, where Chandler says the primarily Latino immigrant population is, to many, a “new phenomenon.”

Throughout the South and nation, immigrant communities are developing. In Mississippi alone the immigrant population is greater than 100,000, Chandler estimates, far more than the census found. Communities are being built, he says, even though workers are often provided sub-par housing and low pay. Some work in conditions comparable to indentured servitude.

Nearly half of immigrants receive low wages according to the Urban Institute analysis of the 2002 Current Population Survey, earning less than double minimum wage. It finds only a third of native born workers are paid similarly. Of immigrant women 13 percent receive less than the minimum wage, the institute reported.

Some unions have found ways to stop the servitude and prosper simultaneously. The builders’ unions—plumbers, painters, carpenters, roofers, etc.—were some of the first to do so, says Chandler.

“It made their unions that much stronger,” he contends, fortifying it with new members, some of whom had struggle experience in their countries of origin that their colleagues could learn from.

According to Jimenez, one of the few issues unions and immigrants rights groups disagree on is guestworker plans, like the one Bush proposed in January.

While immigrant groups support such a proposal, on the condition that it doesn’t bind a worker to one employer, and includes workplace protections and a path to permanent residence, the majority of unions reject temporary plans. Jimenez notes that agricultural unions are the exception.

“There’s still this concept of competition with the American worker, particularly when you have a bad situation in the economy,” she explains.

For the same reason, Chandler finds some unions still discriminate.

“Racism and the labor movement just don’t go together,” he says.

Employers may even utilize racism to keep wages low, Chandler suggests, pointing out it wasn’t until African Americans unionized that Latino immigrant workers were recruited.

Rather than attempting to exclude immigrant workers, unions should try to organize them, he argues.

According to Durazo, some of the unions that have done so went from handfuls to hundreds of members with many undocumented immigrants leading the fight.

While it may not fly in the labor movement, racism and anti-immigrant sentiment did merge during the freedom rides.

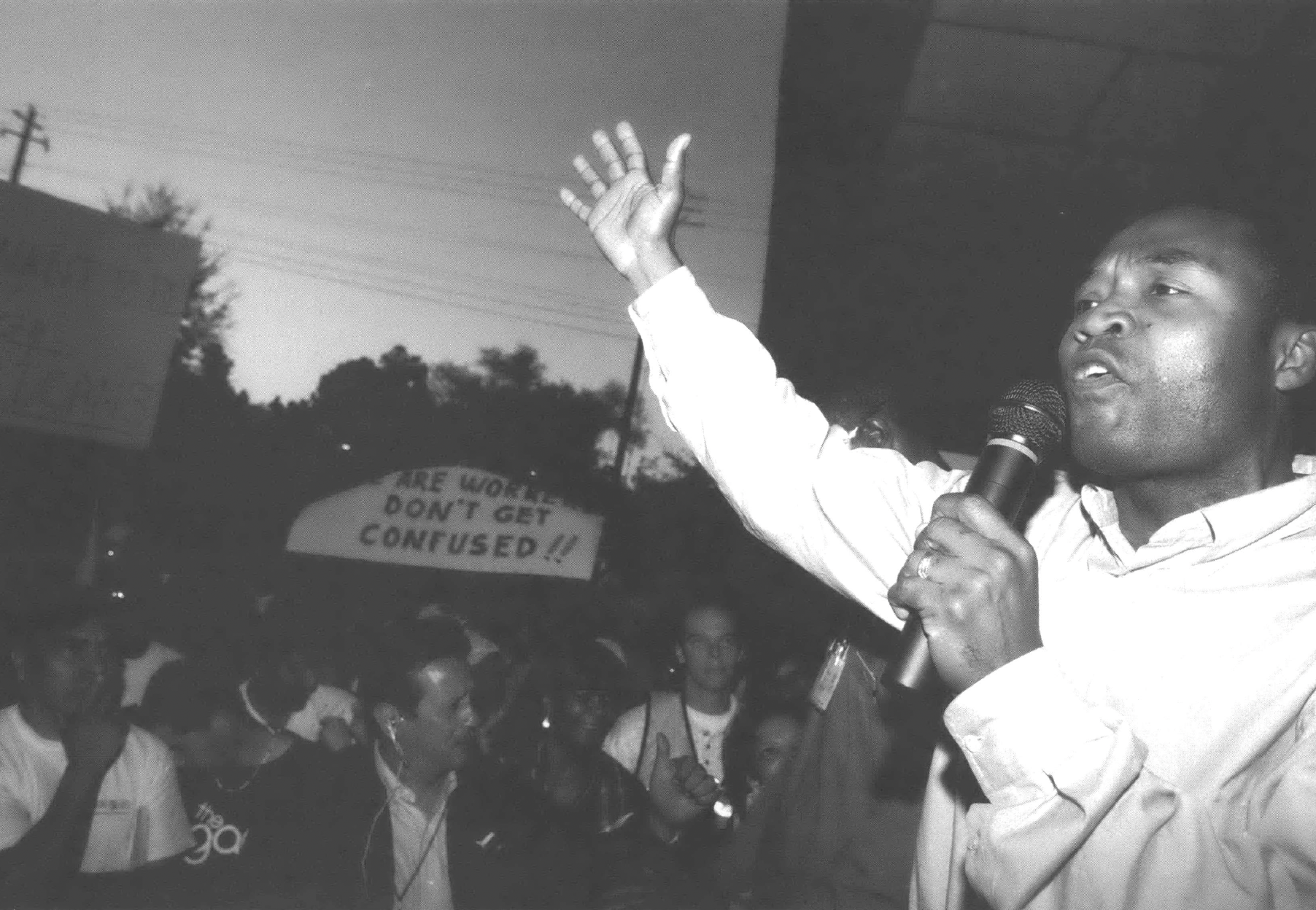

In Doraville, Ga., outside Atlanta, on day four of the Houston route, a march was scheduled from a church back to the union hall where the riders had just finished lunch. The riders were relatively quiet as they walked to the church. For 80 hours they had been going from rally to rally, sleeping only short nights in roadside motels.

As they climbed a shallow hill, the riders looked ahead to see a group of people holding signs. However, these signs did not bear the supportive slogans they’d come to know. Instead, the signs read: “Mexicans Go Home,” “Protect U.S. Jobs,” and, “Stop the Illegal Invasion.”

One man explained that they were protesting the federal government’s inability to protect the U.S.-Mexico border, not the immigrants themselves. As he said this, another woman laughed at the riders. “They can’t even speak English.”

“They are invaders,” said the man.

Anti-immigration organizations are coming together with white supremacy groups, according to Bob Moser, senior writer for the Intelligence Report at the Southern Poverty Law Center.

In the ’50s and ’60s, white supremacists were notorious for lynching blacks and bombing their property.

Moser says at many freedom ride events they and anti-immigration groups “were saying essentially the same thing and standing side by side.” While he hasn’t seen evidence that they are coordinating their efforts, he says that the two groups share a similar message, often saying immigrants are disease ridden rapists.

In Doraville, the dozen protesters gathered to respond to some 3,000 immigrant supporters who met the freedom riders. The large march inspired and reenergized many of the travelers. Doraville advocates rallied primarily around extending driver’s licenses to the undocumented, contending that they helped build the roads and should be able to use them.

Annunciation House in El Paso, Texas, has helped bridge the gaps in international understanding since 1978. It has provided hospitality to 75,000 people, focusing on housing undocumented immigrants, the poorest people in the U.S.-Mexico border city.

Union workers are invited to spend time there, and those that have seen the conditions and low wages Mexican workers endure, says Ruben Garcia, one of the house’s founders.

“They see that the most important thing that they can do right now is participate in the unionization of the Mexican worker,” he contends.

Their battle is not against those workers, they realize, but against a corporate structure, he says.

Mario, a rider aboard the Southern route, explained that he boarded the bus to tell people that he did not migrate to take a job. “We come here to contribute to this country, to the economy of this great nation.”

Durazo agrees, and says that she is proud the AFL-CIO has remained committed to immigrant workers as the economy has taken a dive. In past recessions, she says politicians and employers would often call immigrants the cause of the problem and the labor movement would buckle.

Now the two groups realize they can make great gains in concert.

This summer, the AFL-CIO is planning a voter registration drive targeting immigrants in Arizona and Florida, where the need for immigration policy reform is most dramatic and visible. Border enforcement strategies channel immigrants into the most dangerous parts of the desert in Arizona. There 621 people have died attempting to cross since October, 1998, according to government data. In Florida, many Haitian immigrants are not allowed refugee status and are instead held in detainment camps.

Durazo says this summer’s effort is intended to keep immigration issues “on the front burner” and to follow up the freedom rides. Before being sent to work, the 100-200 organizers will attend training sessions in Mississippi at the end of June. There they will be hosted by black leaders who participated in the state’s Freedom Summer of 1964. That year numerous organizers held a mock election, pitting Freedom Party candidates against actual candidates to show that blacks wanted and were able to vote. Ballots were cast by 93,000 people.

“We want to make sure that we continue to learn from the civil rights leaders of this country,” says Durazo.

One of the central tenets of the black movement, according to both Lewis and King, was that non-violent direct action was key to making gains. Chavez held the same belief when driving the farm workers movement and now the AFL-CIO and immigrant groups may be following suit.

“We’ve got to figure out ways to make it a part of the culture of organizing,” says Durazo, who calls nonviolent resistance “the most important part of the civil rights movement.”

According to Jimenez, “nonviolent direct action has to be a part of the long term strategy of the immigrant movement.”

She says single actions raise consciousness in the general population, strengthen the immigrants performing the act and produce results.

In the long term it can bring about fundamental change, she contends.

Lewis calls the immigrant freedom rides “one of the most moving and meaningful acts of nonviolent protest,” for civil, human and workers rights since the ’60s.

He urges advocates to continue such action on a local, state and regional level while convincing legislators to pass “necessary” legislation.

“Our past is what brought us here, and it can help lead us to where we need to go,” he wrote in his book, Walking with the Wind.

As the immigrant and labor struggles merge, they may find their way in the lessons Lewis learned during the black civil rights movement.

“A people united, driven by a moral purpose, guided by a goal of a just and decent community, are absolutely unstoppable,” he wrote. “It’s not about who wins. It’s not even about who is right. It’s about what is right.”

Tags

Jake Rollow

Jake Rollow and Diana Molina were aboard the nine-day Immigrant Workers Freedom Ride from Houston to New York. He is a staff writer with Hispanic Link News Service in Washington, D. C. She is a photographer and writer based in New Mexico. (2004)

Diana Molina

Jake Rollow and Diana Molina were aboard the nine-day Immigrant Workers Freedom Ride from Houston to New York. He is a staff writer with Hispanic Link News Service in Washington, D. C. She is a photographer and writer based in New Mexico. (2004)