This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 32, "Acts of God." Find more from that issue here.

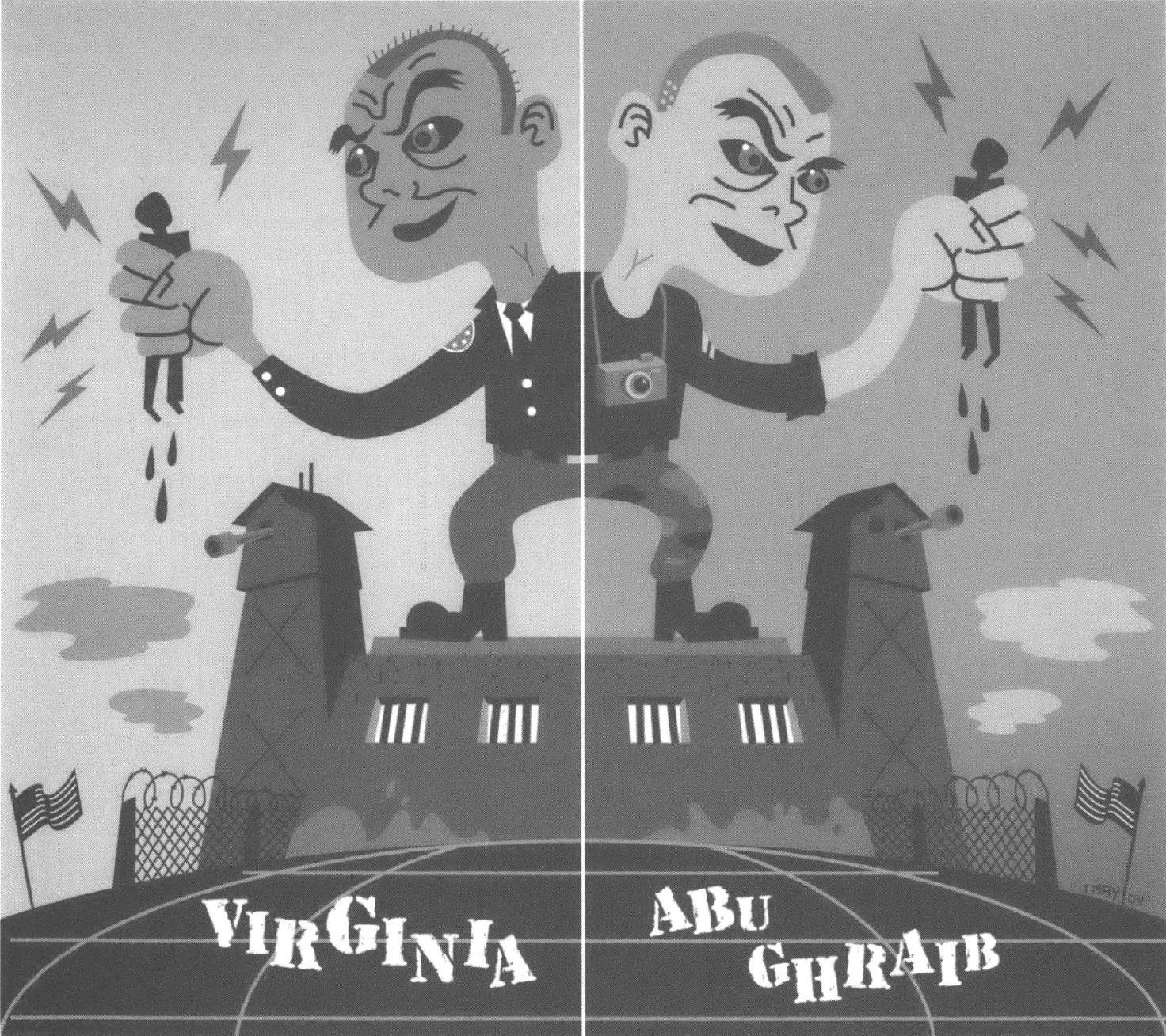

When Albuquerque, N.M., lawyer Paul Livingston first saw the non-infamous photos of the naked Iraqi prisoner being menaced by American soldiers with dogs in Baghdad’s Abu Ghraib Prison, he immediately thought of Virginia.

Livingston represents 66 of 108 New Mexico inmates shipped to Virginia’s Wallens Ridge prison in 1999. The cases, he says, involve inmates who were non-violent offenders and have since been released. Nevertheless, Virginia prison guards beat them, shot them with stun guns and rubber bullets, slammed them against floors and walls, chained them to their beds for days at a time, subjected them to racist verbal abuse, and threatened them with sodomy and vicious dogs. This was done as a matter of policy, Livingston says, “just to show them who was boss and how terrified they should be.”

But while the Abu Ghraib abuse photos provoked international outrage and apologies from President George W. Bush, published reports of incidents in Virginia and other states have left both the president and the public largely unconcerned. Alan Eisner, who discusses Virginia prison abuses at length in his recently published book, Gates of Injustice: The Crisis in America’s Prisons, points out that a videotape made by Texas correctional officials when Bush was the state’s governor in 1996 shows guards using dogs and stun guns to torment naked prisoners as they crawled on the ground.

Bush was not disgusted then. In fact, he presented himself as admirably tough on crime. In a 1999 interview with the now-defunct Talk Magazine, he even made fun of a condemned inmate. “Please don’t kill me,” the future president was reported to have whimpered in imitation of Karla Faye Tucker, “his lips pursed in mock desperation.”

Why was Bush forced to react differently to the abuse of prisoners at Abu Ghraib? Jenni Gainesborough, director of the Washington, D.C., office of Penal Reform International, believes a combination of factors is at work. Photos are powerful, she says. And although the occasional videotape of abuse sometimes surfaces here, U.S. prisons, assisted by U.S. courts, are extremely vigilant when it comes to both preventing such documentation in the first place and destroying it when, inadvertently, it manages to see the light of day.

From Gainesborough’s perspective, the resultant national discussion about the treatment of inmates is a silver lining of sorts. “Suddenly, people are realizing there are international standards, and that there are good reasons to adhere to them,” she says. The lesson for Virginia, she says, is one of culture.

“The reason abuse flourished in Virginia is because it was encouraged and tolerated by [former Virginia Department of Corrections Director Ronald] Angelone. The reason it flourished in Iraq is because of [Secretary of Defense Donald] Rumsfeld and everyone else who says the rules don’t apply to us and we can do whatever we want to do to certain people.”

Angelone, currently a director of the prison contracting company Compudyne, retired from the Virginia Department of Corrections (VDOC) in 2002. Although plagued by allegations of prison brutality throughout his eight-year tenure, he routinely dismissed the charges as the lies of predators and liberals.

While Bush was making fun of Tucker in Texas, Angelone was designing and building supermax prisons, designed to house “the worst of the worst” inmates, in rural western Virginia. When he found, once they were built, that Virginia lacked sufficient “violent predators” with which to fill them, he changed the department’s inmate classification system so that more prisoners would fit the bill. In addition, he opened up the supermaxes for business, bringing in prisoners from overburdened facilities in the District of Columbia, Vermont, Connecticut, New Mexico, and Hawaii.

According to testimony cited by Eisner’s book, Virginia correctional officers at these prisons routinely punished inmates for minor infractions with “the Ultron II, a handheld device that delivers 50,000 volts of electricity; the Taser, which fires electric darts connected to wires; and the ICE shield that is activated to deliver a powerful electric shock whenever a prisoner touches it.” Black and Hispanic prisoners were threatened and made to crawl on the floor.

Larry Frazier, a Connecticut prisoner, was killed by guards who mistook his diabetic convulsions for combative behavior. When a prison contract doctor pointed this out, Angelone had him fired and barred from the prison. When Human Rights Watch issued a report documenting and condemning his policies and practices in the supermaxes, Angelone ignored it. Complaints by out-of-state prisoners, he told members of the Virginia Crime Commission in 2000, were “lies by convicted felons who don’t like being in a tough prison.”

As a result, the Virginia prison system became “one of the worst in the country,” according to Eisner. It is, he says, “the most violent, the most racist, the most ready to resort to force. There’s no accountability anywhere, no independent oversight, and the prisoners have no recourse. The Department of Corrections deems 90 percent of their complaints unfounded. You’re right there with Mississippi, Texas, and Alabama. That’s the company you’re in.”

David Fahti, a lawyer for the National Prison Project who litigated on behalf of the Connecticut inmates sent to Wallens Ridge, was not surprised when he heard that Sgt. Ivan “Chip” Frederick, who tortured prisoners in Abu Ghraib, is a Virginia correctional officer.

“I don’t think it’s an accident,” says Fahti. “Unfortunately, what we’re seeing in the U.S. prisons in Iraq is not qualitatively different from what goes on in American prisons on a fairly routine basis.

Frederick, 38, an Army reservist, was the senior enlisted officer in charge at Abu Ghraib between October and December 2003 (when most of the documented abuses are thought to have occurred). He recently pled guilty to eight charges, including conspiracy to maltreat prisoners, maltreatment of prisoners, dereliction of duty, assault, and indecent acts. In exchange for agreeing to help prosecutors, Frederick received an eight-year prison sentence. In addition, his rank was reduced, his pay forfeited, and he was dishonorably discharged from the Army.

Prior to his tour in Iraq, Frederick spent seven years as a correctional officer at the Buckingham Correctional Center in Dillwyn, Va., where his wife, Martha, still works.

When the charges were first filed, both Frederick and his wife insisted he was innocent and that he was being made to take the fall for policies he neither devised nor carried out. But months later, at his October 20 court martial in Baghdad, Frederick admitted attaching wires to a naked, hooded prisoner and making him stand on a box for hours in the belief that he would be electrocuted if he fell off.

Frederick also admitted to sucker-punching a hooded prisoner and to forcing prisoners to masturbate and pile on top of each other naked. He described how he and other soldiers then jumped on the prisoners, stomping on their hands and feet while “sort of laughing.” Military intelligence officers encouraged such acts, he said, in order to humiliate and break detained Iraqis.

“I didn’t think anyone cared what happened to detainees as long as they didn’t die,” the former correctional officer told the judge.

A photo of Frederick, taken at Abu Ghraib, shows him seated on top of a naked and trussed Iraqi detainee, straddling the man’s head with his boots.

Meanwhile, things haven’t changed much in Virginia. Even with Angelone gone, says ACLU of Virginia director Kent Willis, “we continue to be flooded with mail from Virginia prisoners describing everything from poor medical care to physical abuse by guards.” Angelone himself may be headed back to the public payroll. State Attorney General Jerry Kilgore, the Republican candidate in next year’s gubernatorial race, is said to be considering re-installing him as either head of prisons or state director of public safety.

Tags

Laura LaFay

Laura LaFay, a Virginia writer, covered the state’s prisons for The Virginian-Pilot during the 1990s. (2004)