This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 31 No. 3/4, "Making a Killing." Find more from that issue here.

They gather just before dusk on the old Saunders Hill in Saltville, a small town in southwestern Virginia. More than a dozen teenagers, embers of the Scott Street Baptist Church youth group, file out of a bus onto the field where they set to work with paper bags, sand, and candles. They make these homemade luminaries every Oct. 2 just before 7 p.m. to honor the sacrifice, some say the massacre, of more than 40 black Civil War soldiers who died on this preserved battlefield, where no monument to their sacrifice stands.

Just over 2,000 people call Saltville home. Out of that number, the 2000 census counted only nine black people in the town limits. Yet the annual memorial service is usually an integrated affair, bringing people from several states and differing backgrounds and politics together to help heal the wounds of a nation still torn by the legacies of civil war and slavery. There they sing hymns, pray, and read aloud the names of those still listed as missing by military records.

There was virtually no interest in the story of black soldiers and their fight for freedom until the 1989 release of the movie Glory, which chronicled the formation and battle experiences of the all-black 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Company, says Frank Smith of the African American Civil War Memorial in Washington, D.C. Reclaiming sites such as Saltville and the stories around them “is important as the United States presents itself to the world as a beacon of freedom and democracy.”

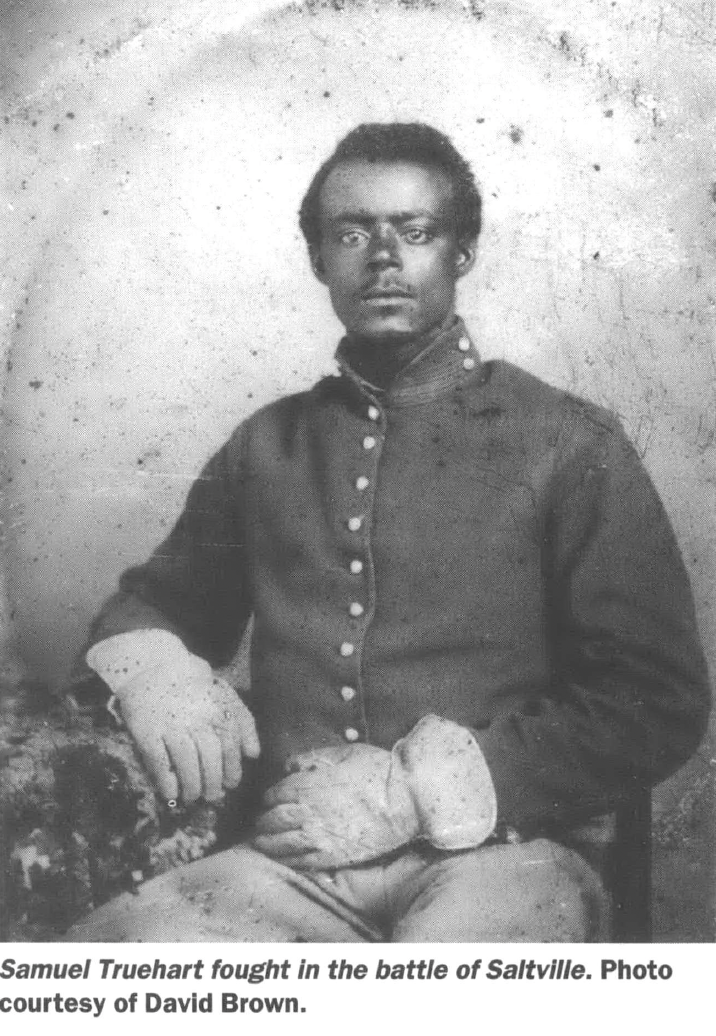

David Brown grew up with a photo of his great-great-grandfather, Samuel Truhart, hanging in the front room of his childhood home in New York state. This fact set him apart from his peers because many black Americans have no record of their families beyond grandparents.

According to Thomas Mays, professor of history at Quincy University in Illinois and author of a book on the massacre, the Truehart photo is one of five existing identifiable photos of black Civil War soldiers. At least 200,000 black soldiers served in the Civil War.

In the old tintype, Truehart is dressed in the uniform of a Union cavalryman—riding pants, gauntlet-style leather gloves, and a blue wool coat with shiny brass buttons. His eyes are clear and resolute, his posture relaxed. The photograph was likely taken in the early autumn of 1864 at Camp Nelson, Ky., where Truehart enlisted in the Fifth United States Colored Cavalry. Within a few weeks, Truehart’s regiment would ride into battle as part of a Union force attempting to destroy a Confederate installation at Saltville.

In 1998, Bill Archer, then a reporter for the Bluefield (W.Va.) Daily Telegraph, heard the story of the Saltville Massacre while covering a battle re-enactment there. Archer, the son of a military man, was astonished. “This is America. These were U.S. soldiers,” he says. “The United States abandoned them; Burbridge abandoned them. How could you leave your wounded?” In fewer than two months, Archer had organized the memorial service.

Archer found David Brown through the Internet and invited him to participate in the service. While conducting research into his family history, Brown compiled a list of the soldiers of the Fifth still missing in action after the war. Brown and his mother, Phyllis Brown (Truehart’s great-granddaughter) were in attendance as those names were read aloud and luminaries were lighted in their honor at the first Saltville memorial service on October 2, 1998, the 134th anniversary of the battle. Every year since 1998, people have gathered in Saltville to honor the sacrifice of these men.

In 1864, Gen. Stephen Gano Burbridge was trying to salvage a sinking military career. A few hundred miles away lay Saltville, Va., the so-called “Salt Capital of the Confederacy.” Mechanical refrigeration did not exist during the Civil War and salt was the only battlefield food preservative. If Burbridge could destroy those salt works and disrupt the South’s food supply, his career might be revived. But he needed troops.

Congress had established the Bureau of Colored Troops in May 1863 to recruit and train black soldiers for the war effort. Burbridge’s state of Kentucky was bitterly divided over the war and many white Kentuckians were unwilling to enlist. So Burbridge, under the auspices of the new bureau, ordered the formation of the Fifth Regiment of the United States Colored Cavalry. Most of the 600 recruits came straight from bondage, but Samuel Truehart, a freeman, also was among the ranks.

The men of the Fifth USCC were given substandard equipment and at most three weeks’ training before they marched off to Saltville with 4,400 white troops. Despite a lack of training and merciless taunting by their white counterparts, the men of the Fifth distinguished themselves in battle at Saltville on Oct. 2, 1864. Ordered to storm a heavily defended hill, the regiment suffered heavy casualties.

One Confederate cavalryman quoted by Mays in his book, The Saltville Massacre, wrote afterwards that he “never saw troops fight like they did. The rebels were firing on them with grape and canister and were mowing them down by the scores but others kept straight on.” A Confederate officer concurred: “I have seen white troops fight in 27 battles and never saw any fight any better” than the men of the Fifth, he wrote.

But Burbridge was a lackluster tactician and his 5,000-man force was routed by half that many Confederates. The general and his remaining forces slipped back to Kentucky under cover of night, abandoning their wounded, many of them black soldiers, to the enemy.

Historians disagree about what happened the next morning. Some argue that another war began—a guerrilla war against black soldiers. Accounts written by Confederate soldiers describe a massacre that lasted for days after the initial battle, as Confederate troops executed black soldiers too wounded to retreat. “They were shooting every wounded Negro they could find,” writes one witness. “Hearing firing on other parts of the field, I knew the same awful work was going on all about me.”

The killing, according to some accounts, extended 12 miles away to a Confederate field hospital at Emory and Henry College, near Abingdon. A field surgeon at the hospital named William Mosgrove later filed a formal complaint with the military alleging the shooting of several black soldiers at the hospital. One Richmond newspaper reported that 155 black soldiers were killed and that Confederates took no prisoners.

A letter written on behalf of Gen. Robert E. Lee by his Aide de Camp Charles Marshall to a Confederate commander hints at an atrocity on Saunder’s Hill:

“He [Lee] is much pained to hear of the treatment the negro prisoners are reported to have received, and agrees with you in entirely condemning it. That a general officer should have been guilty of the crime you mention meets with his unqualified reprobation.”

The letter goes on to encourage the commander to bring charges against the unnamed officer, but no one was ever brought to trial for the killings. Saltville oral history says the executed soldiers were dumped in a sinkhole and a pig pen was erected on the spot to cover the crime.

At least one large set of public pig pens did exist in the town as recently as 40 years ago, Saltville tourism director Charlie Bill Totten says. As a child, he helped clean those pig pens and found a great many buttons, buckles and ribbons in the process. Too many, he says, for that spot to be anything but a mass grave.

Radford University archeologist Cliff Boyd has excavated that and a similar sink hole in town and has not found a mass grave. Residents say there are four other possible spots, but NASA’s ground-penetrating radar couldn’t find evidence of a mass grave anywhere in the town. Even if the bodies were dumped in a sinkhole, Boyd says, they were likely moved soon after. There is little chance that any remains will be recovered.

But David Brown’s great-great-grandfather was not among the dead. Samuel Truehart survived the first battle of Saltville, returning in December 1864 with a Union force that did destroy the salt works (although the Confederates, using 200 slaves, had the installation up and running again within a couple of months). Truehart stayed in the Army through the end of the war and was finally mustered out in Arkansas in 1866. He walked back to Kentucky, where he lived for 12 years before leaving for Kansas as part of the “Exoduster” movement. During those years, hundreds of thousands of African Americans went West, chasing the dream of owning their own land.

Anne Butler has spent much of her professional life preserving and passing on black history. She has worked at Camp Nelson National Historical Park and currently directs the Center of Excellence for the Study of Kentucky African Americans at Kentucky State University. She has consulted on the Saltville memorial service since its inception. “It’s very difficult for African Americans to find connections to geographic place,” she says. “History has been sanitized and our visible presence has been written out. Memorials help us reclaim a local landscape and the histories surrounding an area.”

In fact, the most divisive time in American history now brings people together, Butler says. For the past 15 years across the South, blacks and whites have banded together to preserve and memorialize Civil War history and the part of African Americans in that history. Confederate sympathizers have been known to help black people clean African-American cemeteries. “It shows how complex issues of race really are,” she says.

Saltville resident Eleanor Jones says her grandfather, 14 years old in 1864, witnessed the battle and the massacre from behind Confederate lines. She is proud of her Confederate heritage and says she doesn’t think about slavery when she thinks about the South. “The South means gentility, good manners, and hospitality to me,” she says. But she is a big supporter of the memorial service and dismisses concerns that “dredging up the past” might hurt the town’s fledgling tourism industry. “Veterans deserve recognition,” she says. “It means putting an issue to rest.”

Jim Bordwine, who grew up in Saltville and still lives there, says his great-grandfather may have participated in the massacre. Bordwine always has loved history and now spends most of his free time as a re-enactor. He usually attends the Saltville memorial in Confederate uniform. “Both sides needed to be represented,” he says. “We have to show that we can stand together, that we’re not still fighting.”

Although there is still resistance to reclaiming and telling the history of American blacks across the South, there is also a large contingent that supports opening up that history, says Virginia curator of African-American history Lauranett Lee. Lee has traveled across Virginia touring black history sites and also consults on their preservation and presentation. She believes these sites are drawing African-American families to the South as tourists. “Parents have been concerned about how history is presented,” she says. But now “these families can have a part in the education of their children.”

In fact, everyone benefits from development of these historical sites, especially the small towns like Saltville, Butler says. “There is often an economic gain for them” in the form of tourist dollars. And it may also work for black communities. The African-American Civil War Memorial was built in the historically black Shaw neighborhood for this reason, says Smith.

According to a report by the Travel Industry Association of America, African-American travel increased 16 percent from 1997 to 1999. That increase was much higher than the one percent growth of U.S. travelers overall. The report went on to say that most of those African-American travelers visit the Southeast United States. Phyllis Brown, for one, had never visited the rural South before the first Saltville memorial in 1998.

To Smith, this new trend is a way to “right a great wrong” in American history and help struggling communities. But it’s also about telling the truth. Black Americans built the South, he says. While slave owners were off fighting to preserve slavery, black people grew the food, worked the farms, and maintained the houses of the owners. After the war, black people, including federal veterans, came home to the South to “build a new world,” he says. “It’s a whole new story about the South and how it developed.”

Phyllis Brown feels much the same way. Memorials “tell the world that African-Americans fought for their freedom. They didn’t wait for others to win it for them. They took their future in their own hands.”

For more information

The Saltville Massacre Web site (David Brown’s research) mywebpages.comcast.net/5thuscc

African American Civil War Memorial Web site www.afroamcivilwar.org

National Park Service Civil War Soldiers and Sailors Project (database of soldiers) www.itd.nps.gov/cwss

Saltville, Va. www.saltvilleva.com

Tags

Tonia Moxley

Tonia Moxley has written for several regional publications and has worked in online and print journalism. She is currently a religion columnist at The Roanoke Times. (2003)