This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 31 No. 3/4, "Making a Killing." Find more from that issue here.

The giant steam engine at the Najibiya power plant is quiet. If the Russian engineers who built the original equipment over 30 years ago stopped by to take a look, they might have a hard time recognizing the machinery: over the years Iraqi engineers have replaced many of the original blue parts with a patchwork of white and grey makeshift materials.

Across the street the lights go out. Yaruub Jasim, the general director of electricity for the southern region, a kindly-looking man in his sixties dressed neatly in a grey suit, is apologetic. “Normally we have power 23 hours a day but today there is a problem. We should have done maintenance on these turbines in October, but we had no spare parts and no money.”

Jasim tells us the needed parts were supposed to be supplied by Bechtel, a California-based company in charge of repairing the power system under a contract to restore Iraq’s infrastructure. (A Bechtel spokesperson says that the company was only responsible for “specifying the material design parameters for spare parts,” while it was up to occupation authorities to purchase and deliver the parts.)

Bechtel won the contract last April, before President Bush declared an end to major conflict. The company is to repair and refurbish sewage, water, and school systems to the tune of over a billion dollars and growing, making Bechtel’s business in Iraq second only to Texas-based Halliburton.

Just days before our visit in mid-December, the United States government announced its decision to exclude the countries who opposed the war from winning reconstruction contracts in Iraq. The political ramifications of this ban, and whether it would cover parts suppliers and sub-contractors or not—weighs heavily on Jasim’s mind.

“Three out of four of our power stations were built in Russia, Germany, and France. Unfortunately, Mr Bush prevented the French, Russian, and German companies from [getting contracts in] Iraq three days ago,” he says.

As we walk around the power plant, we notice four brand-new industrial-sized York air-conditioners. “We got those air conditioners two weeks ago—Bechtel sent them to us because our equipment was malfunctioning over the summer, but they haven’t installed them and we don’t need them in the winter,” says Hamad Salem, the plant’s manager. The delay is due to a dispute over whether Bechtel or the power plant itself is responsible for installing the air conditioners.

Who Has the Power?

The engineers in southern Iraq are lucky to only have to explain why the power fails once a day. Their colleague in Baghdad—Mohsen Hassan, the technical director for power generation at the ministry of electricity—has to explain to visitors why there is no power, frequently for over ten hours a day, in the capital city which houses a quarter of Iraq’s population.

A quiet, unassuming man, Hassan wears a checked shirt, no tie, and a brown jacket that might be seen on any street in this city.

“Bechtel has put us in a very difficult position. My minister has said to them if the people get angry, don’t blame us. You know electricity is the first (biggest) problem in Iraq, they must solve this as soon as possible. Under Saddam we fixed everything quickly but we didn’t worry about quality. We didn’t work the standard way, it was very irregular.”

“The Americans have very high standards, ours are very low,” he adds, holding out his hands and bringing them closer together to illustrate his point. “We need to meet in between.” We ask him why Bechtel is so slow, as surely this is a company that is very capable, having built the Saudi Arabian electricity system from scratch. “These are unusual circumstances,” says Hassan. “No security, there is sabotage, the system is upset.”

One of the reasons that Bechtel has taken so long is because its electrical team spent two months simply examining power plants, substations, and high-voltage lines before they started any work, infuriating the Iraqi staff, who say they could have told the company what was necessary. Theft and sabotage has been another problem—as soon as Bechtel started replacing 10 sabotaged electrical towers near Nassiriya, another 10 were destroyed nearby.

Bechtel denies responsibility for the situation. “A lot of people thought the United States was going to come in with a dump truck of money,” Cliff Mumm, head of Bechtel’s Iraq effort, recently told the San Francisco Chronicle. “To just walk in and start fixing Iraq—that’s an unrealistic expectation.”

This reasoning is echoed by U.S. government officials. On a visit to the U.S. Agency for International Development office in the heavily guarded Baghdad convention center next to the Republican Palace, we encounter three Secret Service officers with assault rifles in the central atrium, walking in step, facing different directions, scanning the area constantly. In the center of the imaginary circle they create is an older man in a blazer. He looks like a career politician, and smiles as he chats to the woman walking beside him.

“This looks so splendid,” he proclaims, gesturing at the convention center. We ask the Secret Service guy who he is, perhaps a member of Congress? “No, he’s Ambassador Ted Morse, who runs Baghdad and its suburbs.” I step up and ask him if he will speak to me for a few minutes about the infrastructure problems in the city. He smiles genially. “Of course.”

Morse focuses relentlessly on the positive. “When we came here, the entire city was still without light. The entire city was insecure and there was fighting going on. But now, in terms of the whole city, there has been tremendous, tremendous progress.”

When we tell him that we have talked to the power plant managers, and they have a different story to tell, he insists that everything will be resolved in time. “Six months is a little unrealistic to ask for it [reconstruction] to be over. The bottleneck is sheer time. If you look at how much time it took to rebuild Bosnia, in Sierra Leone, in Rwanda, in Cambodia, in Burundi, in Timor. Wherever you have had a true conflict situation, there is an impatience in that people think it could be done immediately. Never in the world can it be done immediately. It cannot. It’s just a physical engineering constraint and it has nothing to do with Bechtel.”

Mohsen Hassan doesn’t agree. “We, the Iraqi engineers, can repair anything,” he says. “But we need money and spare parts and so far Bechtel has provided us with neither. The only thing that the company has given us so far is promises. We have brought the power generation up to 400 megawatts without any spare parts, but we will need something more than words if we want to provide this city with the 2,800 megawatts that it demands.”

Iraqis point out that the previous regime got things up and running again after the first Gulf war in a matter of months, even though the damage was much more extensive because the United States and Britain deliberately bombed the power infrastructure. This time the invasion avoided targeting power plants, but more than twelve years of United Nations sanctions have taken their toll.

The complaints are not limited to electricity. Telephones don’t work because U.S. and British planes bombed exchanges, and despite some progress, to date Bechtel has yet to finish repairing many of them. And the water system is also in a state of major disrepair, according to Sa’ad Mohammed, the director general of the water department for Baghdad.

“From the beginning, the U.S. considered Iraq like Afghanistan—without infrastructure and expertise,” he told us. “But when they came here, they realized the Iraqis are very different. The biggest problem is that the money allocated for water and sewage from the $18 billion US budget is not enough.” he told us.

Yet activists have long warned that the twelve-plus years of United Nations sanctions had severely impacted utilities because it was practically impossible to buy spare parts. A report by the New York-based Global Policy Forum in August 2001 states: “Civilian infrastructure has suffered disproportionately from the lack of maintenance and investment. For example, Iraq’s electrical sector is barely holding production steady at one-third of its 1990 capacity even though government expenditure in the sector consistently exceeds plans. Electrical shortages, worst during the hot summers, spoil food and medicine and stop water purification, sewage treatment, and irrigated agriculture, interfering with all aspects of life.”

Suffer Little Children

The situation in Iraq’s schools—which Bechtel was supposed to have repaired over the summer—is not much better. Complaints about shoddy or undone school repairs have recently brought high-level outside scrutiny. An internal study by U.S. Army personnel, surveying Iraqi education ministry staff and school principals and recently leaked to Cox Newspapers, strongly criticized Bechtel’s attempts to renovate Iraqi schools.

“The new fans are cheap and burned out immediately upon use. All inspected were already broken,” wrote a U.S. soldier. “Lousy paint job. Major clean-up work required. Bathrooms in poor condition,” wrote another about a different school.

Much of the criticism focuses on Bechtel’s Iraqi subcontractors. “The contractor has demanded the schools’ managers to hand over the good and broken furniture. The names of the subcontractors are unknown to us because they did not come to our office,” wrote an Iraqi school planner.

“In almost every case, the paint jobs were done in a hurry, causing more damage to the appearance of the school than in terms of providing a finish that will protect the structure. In one case, the paint job actually damaged critical lab equipment, making it unusable.”

Bechtel officials defend their work. “The people at Bechtel really care about this one. We’ve all got kids. We’ve all been to school. In a country with a lot of hurt, this is meaningful. So, it’s a system, it’s people who care and it’s being done in the middle of chaos, chaos evolving into something more orderly and more Iraqi,” Bechtel’s Gregory Huger, a manager in the reconstruction program, told a Cox reporter.

To find out for ourselves, we visit four Baghdad schools (all listed as renovated by Bechtel), beginning with Al-Harthia, a low white building that houses 570 elementary school students. Here we meet Huda Sabah Abdurasiq, who loses no time in showing us all that is wrong. The rain leaks through the ceiling, shorting out the power. The new paint is peeling and the floor has not been completely repaired, she says.

Most shocking to Hilda is the price tag: “I could fix everything here for just $1,000. Mr. Jeff [a Bechtel subcontractor] spent $20,000!” she fumes. She went to the district council and complained and then marched off to the convention center to confront the military. “They were very angry and spoke to our councilmember Hassan but nothing happened. And we have no receipts for money spent. It’s useless, they won’t do a thing,” she says.

We head over to Al-Wathba school, easily in the worst condition of all the schools we visit. Ahmad Abdu-satar, a friendly man in a dapper suit who has worked here for two years, shows us the toilets and sinks: new brass taps and doors painted a dark blue but the sinks are in a terrible state, they don’t look like they have been touched in a decade. There is no new paint on any of the walls, and, like the previous school, the playground is flooded.

“I’ve been thinking of turning it into a swimming pool,” he remarks sarcastically. “Honestly, nothing has changed since Saddam’s time. I ask you, would American children use these toilets?” We tell him that budgets have been slashed in America and teachers fired en masse, but he repeats his question: “I ask you, would American children use these toilets?” We are forced to concede that the answer is no.”

We have no books, no stationary, nothing. At least we had that in Saddam’s time. Yes, our salaries have gone up, but so have prices. When I asked the contractor why they didn’t finish the job, they said: we don’t work for you, we work for the Americans.”

We stop briefly at the Al Raja’a school, but it is still being repaired. Jamal Salih, the guard, shows us around, then complains that he had asked the contractor to fix his house, but they refused. We take a peek inside, surprising his two daughters and wife who are busy preparing a meal of potato chips for lunch. The workers also invite us to join them for their falafel lunch, but we decline and hasten to the last stop of the day before the school closes at one p.m.

This is Hawa school, run by Batool Mahdi Hussain. Hussain is a tall woman, dressed all in brown, including her traditional Islamic headscarf. She appears young for the 11 years she has spent at this school, which she recently took over when the parents voted her in as headmistress after the war. Like the two previous headmistresses, she is eager to talk and show us around.

She is also bitter about the contractors. The school has a fresh coat of paint on the outside with all of the characters from the Disney version of Aladdin, complete with the genie and the prince.

But, she says, things are worse than under Saddam. “UNICEF painted our walls and gave us new Japanese fans. They painted the cartoons outside. When the American contractors came, they took away our Japanese fans and replaced them with Syrian fans that don’t work,” she says angrily.

We are joined by the school guard, Ali Sekran, who speaks a few words of English. He repeatedly uses his AK-47 as a pointer to help Hussain illustrate all the problems. We pray that the gun isn’t loaded.

The headmistress takes us to the toilets where a new water system has been installed, pipes, taps and a motor to pump the water. The problem is the motor doesn’t work so the toilets reek with unflushed sewage. She then uncovers a new drain cover to show us that it is nothing but a cover. She walks quickly, not waiting for the camera to catch up, a whirlwind of show-and-tell. “These doors, the hinges are broken. We were supposed to get steel doors, we got wooden doors. The new paint is peeling off. There isn’t enough power to run our school.”

We notice a brand new blackboard. Hussain says that the teachers paid for it out of their own pocket. As we bid farewell, she walks us out of the gate and points to the construction debris in the road.

“They didn’t even take their rubbish with them. They gave us no papers to tell us what they had done and what they did not do. We had to pay to haul the trash. Honestly, the condition of our school was better before the contractors came.”

Bechtel Baghdad spokesman Francis Canavan says the company has “received inquiries” on a number of the schools it contracted to repair. He says Bechtel has directed its subcontractors to make repairs, and is withholding 10 percent of the subcontractors’ payment to ensure that repairs will be made.

But the United States Agency for International Development (AID) is unapologetic about the state of the schools. An official spokesperson tells us: “If you are going to do a slam article that complains that the paint is peeling on a school that we didn’t fix, I don’t see why I should talk to you. I don’t even know that you went to schools that were fixed by AID—26 of the 52 schools that have submitted complaints were not even part of our contract.” We assure her that we only visited schools that were listed by Bechtel, showing her Bechtel’s own list. She acknowledged the list with bad grace, clearly rattled by numerous news reports of the failure of the school repair program which officials had hoped would bring them much-needed positive publicity.

Despite the spokesperson’s acceptance of the school list, Canavan, in a later email response, told us he can’t find the schools we visited on Bechtel’s list. He noted, however, that “school names change, and the English spelling of school names in Iraq varies.” At press time, Bechtel has agreed to help Southern Exposure clear up any uncertainties about who worked on these schools.

In any case, this episode points up another problem that seems to plague the Iraq reconstruction business: a frequent confusion among Iraqis, occupation authorities, and contractors over who’s responsible for what, which can contribute to disputes and delays.

Making a Killing

To its credit, Bechtel is one of the few companies that has made extensive use of local contractors and holds regular meetings to explain how to get work from them. It is also the most accessible to the international press, being the only company to maintain offices at the Baghdad convention center where the U.S. military holds trainings, meetings, and press conferences for the outside world.

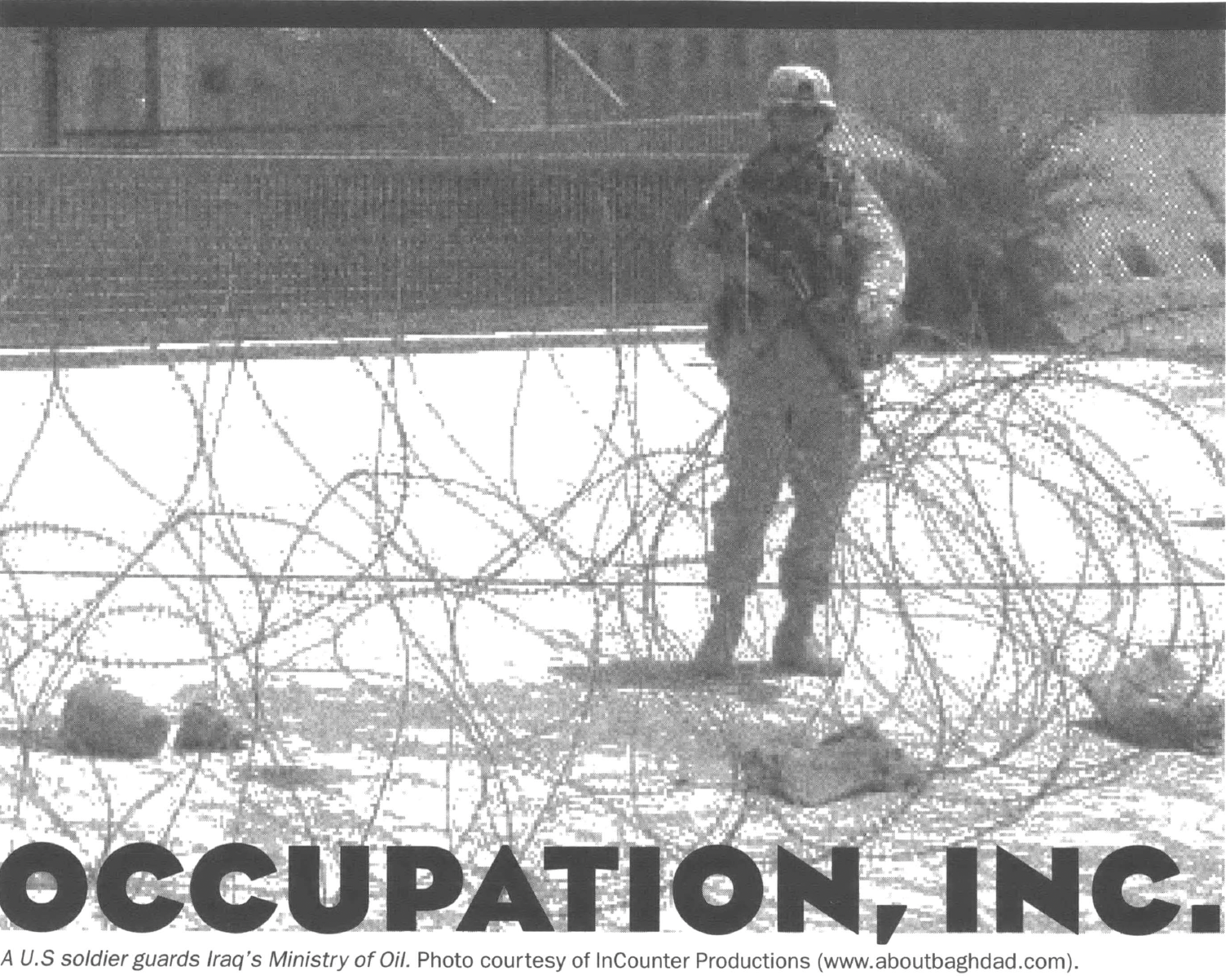

However, the company is not as accessible to ordinary Iraqis. Getting to Bechtel’s offices isn’t easy. It takes half an hour on a good day to get through three body searches and a maze of barbed wire, sandbags, solid concrete road blocks, and soldiers, designed to keep out suicide bombers.

Visitors to the basement of the convention center where Bechtel keeps its offices might meet Maniram Gurung outside the United States consul’s office. Standing in front of photographs of Bush, Cheney, and Powell, Gurung watches American soldiers, Iraqi government officials, and contractors hurry by in the business of nation-building.

For the retired Gurkha rifleman from Kathmandu, Nepal, this guard duty is yet another boring but well-paying job, allowing him to send $1,300 home to his family, a small fortune in his country. It’s not as much as he used to earn when he had to retire from the British Army in 1990 at $2,500 a month, but it helps pay the bills. And there are some advantages—this job is only for six months whereas in the British Army he could only go home from his rotation in exotic locales like Brunei and Hong Kong once every three years.

But Gurung is not a member of the coalition forces—his red badge identifies him as an employee of a private security company called Global Risk. Some 500 Gurkhas and 500 Fijians make up the bulk of this British company’s armed staff, and as a security force for the CPA, they face just as much danger and resentment as the soldiers. In early August a Gurkha was killed by a bomb in Basra. Today they are confined to their barracks at night, eight men to a trailer home, and food is strictly “English” (a euphemism to mean Western food), provided by Kellogg, Brown & Root sweatshop cooks from India whose base pay is just three dollars a day.

Why all this security? Almost every day a U.S. soldier is killed by the well-hidden but determined Iraqi resistance, and in recent weeks they have started to target the companies that are profiting from the occupation.

This summer, a Bechtel engineer and four guards were attacked by a crowd that hurled giant chunks of ripped-up concrete at the business executives in the SUV they were traveling in, shattering most of the windows.

Today U.S. and European businessmen travel with caution in what has become the unofficial transportation of the war profiteers: shiny new white GMC Suburbans. Often their vehicles are flanked by two other SUVs filled with gun-toting private security guards.

While guards like Gurung make a relatively princely salary by Middle Eastern standards, their Iraqi counterparts make far less. Mohammed al-Husany, the ever cheerful head of security at the Palestine Hotel’s outer barricade, tells us that he makes just 100 dollars a month, not enough to support his wife and two kids. “I want a job with the American companies. I have a second degree black belt in karate and I know how to fire every kind of weapon. AK-47s, M-16s, all of them. But my friends who work for Halliburton’s security make $400 dollars a month and the American security guards even more,” he confides to us.

Not that the security and barricades have prevented all Iraqi resisters. Did we see the bombing of the hotel last week?, he asks. “The rockets went just one meter over my head,” he says, imitating the sound of the missile. “They fired it from a donkey cart. Now no more animals allowed around here.”

But as far as we have been able to determine, most Iraqi security guards rarely make over $100 a month for five 12-hour shifts a week. Their employers, however (and there are dozens of Western security companies in Iraq today), make a killing selling their services. A contract seen by Southern Exposure from Group 4 Falck, a British security company, offered the CPA two armed guards 24 hour a day for any building for $6106 a month, of which the Iraqi guards’ salaries amounted to just 10 percent of the costs.

War Profiteering?

The three employees of Kellogg, Brown, and Root (a Halliburton subsidiary), standing at the base of a stairwell at the convention center chatting on their tea break, are excited. Khaled Ali tries several times to pronounce the word “congratulations” but fails. Exasperated, he turns to me to ask if there is a better word. I suggest slapping his friend on the back and saying: Good job! Well done! But he shakes his head violently. “No, I cannot say that—Mr. Lewis is an American, my boss. I must say something more polite.”

We start talking. Khaled Ali is an engineer in charge of construction at the convention center, Sabah Adel Mostafa is an interpreter, and Daoud Farrod is a supervisor. Farrod is older but the first two are in their late twenties. They are friends and live in the same neighborhood. Every morning Halliburton sends a car to pick them up and bring them to work at 8 a.m. and take them back at 4 p.m.

They are enthusiastic about their work. “It’s my first job. I was not able to practice my English before. And the [previous government] pay was just $10 a month,” Mostafa tells me. Ali says it his first job, too. “And you are in charge of all the construction here,” I ask. He nods proudly, beaming when we say “Congratulations!” Mostafa earns $200 a month, right in the middle of the typical pay scale for Halliburton’s Iraqi workers, which ranges from $100 to $300 a month. By comparison, Houston engineers can make as much as $900 a day.

If the local staff gets paid so little, the question is what happens to the rest of the money? To date, Halliburton has made over $2.2 billion from the war in Iraq but, unlike Bechtel, most of this money is not for fixing Iraq’s destroyed and crumbling infrastructure. Some 42% is spent on combating oil fires and fixing oil pipelines, 48% is for supporting the needs of the occupying army (such as housing and transportation for troops), leaving just 10% for meeting community needs in Iraq.

Breaking down the numbers reveals some startling details: Halliburton has spent $40 million to support the unsuccessful search for weapons of mass destruction—enough to support 6,600 families in Iraq for a year (at $500 a month, the number cited by many Iraqis as necessary for a decent standard of living).

Other numbers are just as startling—Halliburton’s net profit for the second quarter of 2003 was $26 million, which contrasts markedly with the company’s net loss of $498 million in the same quarter of 2002. Most of its new income is from the contracts in Iraq. “Iraq was a very nice boost” for the company, an analyst told The Wall Street Journal.

Easily the most controversial contract that the company has won in Iraq is for fuel transportation. The importing of gasoline has proved to be among the most costly elements of the reconstruction effort. Although Iraq has some of the biggest oil reserves in the world, production has ground to a halt because of pipeline sabotage, power failures, and an outdated infrastructure affected by more than twelve years of United Nations sanctions.

The United States has been paying Halliburton an average of $2.64 a gallon to import gasoline to Iraq from Kuwait, more than twice what others are paying to truck in Kuwaiti fuel, government documents show. In some cases Halliburton has even charged the government as much as $3.09 a gallon. Wendy Hall, a Halliburton spokesperson, defends the company’s astronomical charges for gasoline. “It is expensive to purchase, ship, and deliver fuel into a wartime situation, especially when you are limited by short-duration contracting.”

The prices Halliburton is charging for gasoline were first uncovered by two Democrats in Congress, John Dingell of Michigan and Henry Waxman of California. Documents they recently obtained from the Army Corps of Engineers show that Halliburton gets 26 cents a gallon for its overhead and fee, but this does not include the company’s profits, which will be determined at the end of the contract and may be as high as 9 percent, depending on the Army’s evaluation of the services provided.

“I have never seen anything like this in my life,” Phil Verleger, a California oil economist and the president of the consulting firm PK Verleger, told the New York Times. “That’s a monopoly premium—that’s the only term to describe it. Every logistical firm or oil subsidiary in the United States and Europe would salivate to have that sort of contract.”

Meanwhile, Iraq’s state oil company, SOMO, pays 96 cents a gallon to bring in gasoline. Both SOMO and Halliburton’s subcontractor deliver gasoline to the same depots in Iraq and often use the same military escorts.

The good news about Halliburton’s overcharging is that these prices have not been passed on to Iraqi consumers directly. The price of fuel sold in Iraq, set by the government, is 5 cents to 15 cents a gallon, the same price as before the war.

Yet these numbers are cold comfort to most Baghdad citizens, because there is very little gasoline available for sale. One must spend at least four hours to buy gas at the pump and often much longer.

The bad news for Iraqis is that the money for Halliburton’s gas contract has come principally from the United Nations oil-for-food program (now called the Iraq Development Fund), money that should rightfully be spent on food and basic necessities for the Iraqi people rather than paid to Halliburton for expensive oil imports, though some of the costs have been borne by American taxpayers.

An internal Pentagon audit has confirmed the overcharging, indicating that Halliburton billed the government an extra $61 million for gasoline (and also attempted to overcharge by $67 million for dining services for the military).

On our way back from our interviews, we pass yet another line for gasoline: it stretches around the block and all the way across the bridge over the river. We decide to chat with the men waiting in line. We are quickly surrounded by angry people.”

We were a rich country—now our very wealth has been stolen by the Americans,” says one. “Under Saddam we never had to wait in line for benzene [the local word for gas or petrol], now we must spend half a day and then sometimes they run out,” says another. The popular theory is that Americans are re-selling the high quality Iraqi gasoline to other countries or keeping it for themselves. “They sell us Turkish or Kuwaiti or Saudi oil. This is bad for our engines and creates more pollution.” One little boy joins the fray: “George Bush Ali Baba, George Bush Ali Baba.” (Ali Baba is the popular local term for thief, popularized by the U.S. military to refer to looters. Now, according to the New York Times, Iraqis use the term to refer to occupation forces.)

Just a block away from the gas station, it is possible to buy black market gasoline for one dollar a gallon—ten times more than at the pump. We decide to buy from the black marketers, and ask the man why he chooses to sell the gas at such a high mark-up. “Listen, I used to be an electrical engineer. Now I have no job. Who will feed my wife and three children?” he asks.

Despite all the private security and the tens of thousands of troops, life for ordinary Iraqis has unquestionably become far worse: two blocks from our hotel, a man was shot in the head and lay bleeding. A passerby discovered him and took him to the police station, but the police refused to investigate.

“What has happened to Iraq? We are in a state of chaos,” says the black marketer. “This is a complete break-down of our civilization. The other day I was called in to have my passport stamped by the occupation authorities. Me, an Iraqi citizen, I have to have my existence verified by these Americans. And I have to bribe the man to get an interview. When I told the Americans that I had to pay a bribe, they told me I shouldn’t have and I said: well, if you paid him a decent salary, maybe he wouldn’t have to ask for a bribe. But no, they pay people the same as under Saddam.”

Propaganda for the People

Dressed in regulation camouflage khakis, the G.I. from the First Armored Battalion is causing a minor traffic jam by handing out newspapers in the middle of traffic at the Sahar Antar (Sahar means roundabout) in the Al Adamiyah neighborhood. His fellow soldiers watch warily from their Humvee and Bradley convoy parked to the side, just in case anyone decides to take a potshot at their colleague.

We gasp as we flip open our copy of Baghdad Now, a bilingual newspaper issued by the military. Two headlines read “Operation Iron Hammer Nets Terrorists” and “Iraqi-American Friendship on the rise.” Pratap has a flashback to Cold War propaganda in India 20 years ago (“Soviet-Indian Friendship on the rise”). Similarly, a page five article on the ribbon-cutting ceremony at the dedication of a renovated engineering building reminds us of the filler articles one might see in newspapers from the former Soviet bloc.

On the front cover is a photo of an Iraqi Civil Defense Corps (ICDC) soldier toting an M-16 and looking as menacing as possible. A page six article headlined “Iraq’s New Defenders” starts, “In addition to the new national army being formed to defend Iraq’s borders in the post-Saddam worked, the ICDC has been created to aid in policing the nation’s cities.” No mention of poor salaries here, although more than half of the new recruits to the Iraqi army have already quit because of low pay.

Writes Colonel Brad May of the 2nd Armored Cavalry Regiment, “Iraq is for the people of Iraq. Every day I see more and more signs that this statement is true. The Iraqi people are well on their way to leading their country into the future: children walk to school, buses crowd the street carrying people to their destinations, and street vendors compete against each other for your business.”

We show this paper to Dr. Aziz, who runs a small printing business just outside the Sheraton hotel in Baghdad. He glances at it and grimaces. He explains that the American government should stop telling the Iraqi people how lucky they are and start fixing the problems, otherwise even their supporters are going to start protesting. “Please tell your readers that we are a civilized people and we cannot tolerate this any more.”

Tags

Pratap Chatterjee

Pratap Chatterjee is managing editor for Corpwatch (http://www.corpwatch.org) in Oakland, California, and Herbert Docena works for the Bangkok office of Focus on the Global South (http://www.focusweb.org). This piece was made possible in part due to support from the Fund for Investigative Journalism, the Fund for Constitutional Government, and the Bob Hall Investigative Action Fund. (2003)

Herbert Docena

Pratap Chatterjee is managing editor for Corpwatch (http://www.corpwatch.org) in Oakland, California, and Herbert Docena works for the Bangkok office of Focus on the Global South (http://www.focusweb.org). This piece was made possible in part due to support from the Fund for Investigative Journalism, the Fund for Constitutional Government, and the Bob Hall Investigative Action Fund. (2003)