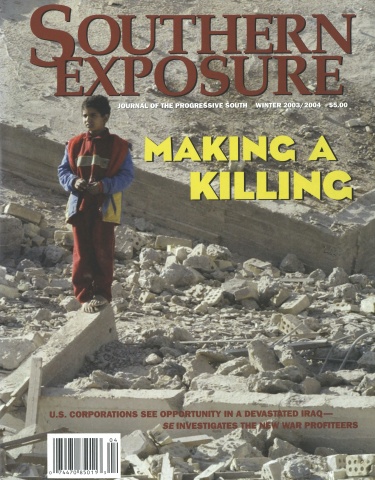

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 31 No. 3/4, "Making a Killing." Find more from that issue here.

“President Bush is asking Congress for $80 billion dollars to rebuild Iraq. And when you make out that check, remember there are two Ls in Halliburton. ”

—David Letterman, Late Show, September 2003

I. When all-purpose conglomerate Halliburton Co. was recently criticized for landing no-bid government contracts worth billions of dollars for post-war reconstruction in Iraq, the company’s Dallas-based executives must have been taken somewhat by surprise.

After all, it’s not like this was the first time the company had benefited handsomely from the spoils of war. Shortly after the 9/11 tragedies, Halliburton had been discreetly handed a non-competitive, no-cap, multi-year deal for “forward deployment” operations, earning them over a billion dollars and counting.

That deal failed to elicit mainstream outrage, as did the fact that, as National Public Radio journalist John Barnett recently revealed, Halliburton’s government contracts doubled from 1995 to 2000, when Dick Cheney was at the company’s helm and Democratic President Bill Clinton in the White House.

Halliburton’s windfalls from war—like those of most other companies that have benefited from an aggressive U.S. foreign policy—are rooted in a long-running, bipartisan confluence of government policy and corporate power. Indeed, it was in 1962 that Halliburton took over Brown and Root, a Texas company instrumental in launching the career of one Senator Lyndon B. Johnson. Johnson returned the favor during the Vietnam War, steering millions in military contracts to his long-time backers.

Then, as now, allegations flew of favoritism, corruption, and profiteering by well-connected corporations. Leading the charge? An upstart Congressional Representative from Illinois, Donald Rumsfield.

“There is such a thirst for gain [among military suppliers] . . . that it is enough to make one curse their own Species, for possessing so little virtue and patriotism. ”

—President George Washington, 1778

II. As long as there has been war, there have been enterprising individuals willing to take advantage of desperate or ambitious combatants.

As historian Stuart Brandes notes in his pioneering history of war profiteering, Warhogs, in 1672 a South Carolina gunsmith named Thomas Ashcraft “became the first American defense contractor jailed for poor workmanship and nonfulfillment of contract.”

By the Revolutionary War a century later, all forms of profiteering—from fraud and price gouging, to plunder and trading with the enemy—were seen as downright unpatriotic. In 1780, the North Carolina legislature moved to limit war profits after determining that “extravagant” prices were resulting from the “wicked arts of a set of men called speculators.” During the Civil War, sensational price-gouging scandals and other cases of fraud, such as allegations that troops North and South were going “half-naked” thanks to cheaply-made uniforms, led to howls of public outrage and calls for reform.

But it wasn’t until 1898, when the United States launched its first major bid for overseas empire with incursions into Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines, that a genuine movement against war profiteering took hold.

As the U.S. military rapidly expanded—despite the absence of an enemy threat, the army budget increased by a factor of 30 and naval spending increased 40-fold— populists, Progressives, religious pacifists, isolationists, and others took the critique of war profiteering one step further, arguing that not only were the “Merchants of Death” capitalizing from conflict, they were deliberately driving the nation to war.

The burgeoning anti-profiteering movement found a sympathetic ear in the South and Midwest, regions largely bypassed by the military fortunes accumulated by military-related businesses in the North and West. In 1916, Representative Claude Kitchin of North Carolina—responding to the anti-war convictions of his constituents—successfully pressed for the country’s first “excess profits tax,” aimed at reining in the egregious gains made by munitions manufacturers such as DuPont, which enjoyed a 1000 percent increase in profits in the three years before World War I.

Outrage over the skyrocketing profits of war-time robber barons before and after the first world war carried into the 1930s, when the anti-profiteering movement hit full steam. By 1935, organizations including the Veterans of Foreign Wars, the American Federation of Labor, the National Grange, and the Democratic Party embraced the anti-profiteering cause. Popular agitation emboldened politicians such as Sen. Gerald Nye of North Dakota, who launched his own three-year, Congressionally-backed investigation into collusion between government and the arms industry.

The movement was to have a lasting impact on the consciousness of the nation, not least some of the country’s most prominent political leaders. Presidents Wilson, Harding, and Franklin D. Roosevelt all spoke against excessive windfalls from war. As a Senator, Harry Truman denounced war profiteering as “treason.” President Eisenhower, who ended his presidency by warning of the encroaching power of the “military-industrial complex,” traced his concern back to his involvement in the War Policies Board of 1930, which investigated charges of persistent war profiteering.

“I don’t want to see a single war millionaire created in the United States as a result of this world disaster. ” President Franklin D. Roosevelt, during World War II

III. Today, war profiteering has become more sophisticated, driven by an increasingly integrated network of military contractors, lobbying operations, and pro-military politicians, many who have revolved in and out of government positions. Unlike the early 20th century, war-related business have found a receptive home in the South, which increasingly is linking its economic future to military expansion (see “Missiles and Magnolias,” Southern Exposure, Spring 2002).

The dramatic increase of military work given to private contractors (by one estimate, a third of expenditures for the Iraq war) has made war an even more lucrative enterprise—which, as Jason Vest reveals in this issue, has given rise to a powerful lobby motivated to secure the spoils of intervention and reconstruction.

But as Pratap Chatterjee and Herbert Docena show, the basic tactics of the war profiteer—over-charging, cutting corners, and seeking to conceal the truth about what is going on—remain familiar. Indeed, the Bush administration’s open policy of connecting the Iraq military operation to economic goals of controlling the country’s oil, water and other key resources and industries has drawn charges that the U.S. is engaging in that most elemental form of war profiteering: plunder.

Yet as before, there are signs that the latest round of companies making a killing from war will spark public and political resistance. As soldiers and civilians bear increasing hardship from the newest quest for empire, a growing chorus is demanding information, accountability, and justice, so that, as President Roosevelt demanded over 50 years ago, no more millionaires are made from war.

Tags

Chris Kromm

Chris Kromm is executive director of the Institute for Southern Studies and publisher of the Institute's online magazine, Facing South.