Driven to Misery

Michael Hudson

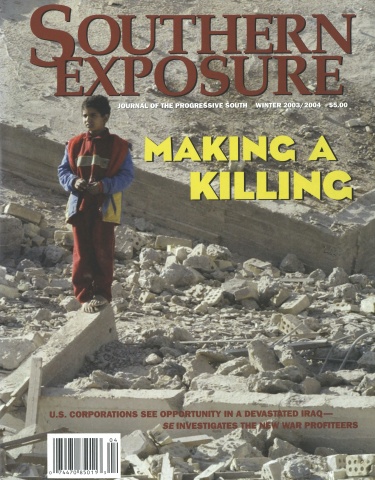

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 31 No. 3/4, "Making a Killing." Find more from that issue here.

Bad credit? Bankruptcy? No down payment? No problem.

It was easy for the boys in “special finance” to qualify down-on-their-luck customers for loans that would put them behind the wheel of a car. Kenny Burgess and Jeffrey Preece, friends and co-workers at Crown Pontiac-Buick-GMC in Nitro, W.Va., knew the drill well. All they needed, they say, were some basic tools: a photocopier, scissors or a razor blade, Scotch tape, a fax machine . . . and a willingness to follow the system that their counterparts at AmeriCredit Financial Services had laid out for them.

Burgess and Preece say they were just doing what they’d been trained to do by their dealership and by AmeriCredit—create fake pay stubs and false down payments that would secure customers high-priced financing from AmeriCredit.

They had all sorts of names for the fictitious down payments: funny money, Crown rebates, Kenny Burgess Cash (KBC for short). Burgess and Preece would fax a financing package to AmeriCredit’s Charleston office and then haggle over the details with the auto financier’s representatives. Sometimes, Burgess said, AmeriCredit would zip back the documents with a question, just for clarification’s sake: “Is it KBC or is it real?”

Other times, Burgess said, AmeriCredit representatives would let them know the doctored pay stubs were unacceptable—not because they’d been faked, but because the fakes weren’t good enough, and the inflated customer income numbers looked a bit, well, askew. Once, Burgess said, an AmeriCredit employee called and told them, laughing, to do it over: “Damn, guys, get the thing straight. It ain’t straight.”

AmeriCredit and Crown Pontiac weren’t doing customers any favors by playing games with the paperwork, according to a lawsuit filed in U.S. District Court in Charleston. In fact, the suit charged, they were confederates in an ongoing scheme that enriched AmeriCredit and a cluster of West Virginia car dealers by slapping customers with hidden costs and preying on their lack of financial acumen.

Addie Coleman had some blemishes on her credit history when she went in to buy a car from Beaman Pontiac in Nashville.

The dealership faxed her loan application to General Motors Acceptance Corp. GMAC weighed the information and came back with a decision: Coleman qualified for an annual percentage rate of 18.25.

But that’s not the APR the dealership wrote into the contract it presented to her. Instead, it boosted the already steep rate approved by GMAC by another 2.5 points, to 20.75.

It was, according to Coleman’s attorneys, a secret markup that over the life of the loan would cost her an extra $809 in finance charges—money that she says could have been used to pay for her daughter’s school but instead, her attorneys say, was divvied up among Beaman Pontiac employees and managers and used to fatten the dealership’s bottom line.

Coleman’s experience wasn’t an isolated one. According to a federal class-action lawsuit, other GMAC customers around Nashville were secretly assessed finance-charge markups of $5,501, $6,018, even $8,600.

The lawsuit claimed these borrowers and many thousands like them were victims of a shady, lucrative arrangement between GMAC and dealers that soaks African American and Hispanic borrowers with covert costs that have nothing to do with their creditworthiness.

Profits and Ingenuity

Most people understand that buying a car is an enterprise fraught with perils: a hazard-filled task where consumers must tread carefully lest they fall victim to outrageous rates, hidden charges, and other abuses. But few realize that the all-too-common traps and rip-offs of the car business are no longer simply the folkways of a decentralized assortment of local or fly-by-night operators. The industry’s unwholesome habits have become, instead, institutionalized practices fueled by top-down market forces and corporate ingenuity.

Addie Coleman’s lender, GMAC, is one of a growing number of name-brand financiers that have been accused of gouging millions of minority car buyers. Others include units of Nissan, Toyota, Ford and Honda.

AmeriCredit, meanwhile, is the nation’s biggest lender to car buyers with patchy credit, claiming more than 1 million customers and a loan portfolio surpassing $15 billion. The Fort Worth-based company has also been distinguished by a history of allegations of securities fraud, predatory lending and, recently, insider trading. In November, AmeriCredit and its co-defendant, Crown Pontiac, agreed to pay a settlement of as much as $75,000 to end a federal lawsuit involving about 60 West Virginia customers.

A second class action is still pending in state court in Lincoln County, W.Va.; that lawsuit accuses AmeriCredit of directing a “credit financing scam” at a Charleston dealership. Among the victims, the suit claims, was a woman who depends on Social Security disability income and cannot read or write. The suit alleges that the dealership promised to give Diana Woodrum the lowest possible rate because of her son’s heart transplant, then socked her with a 16.95 annual percentage rate and a hidden charge of $3,000. When she and her husband protested, the suit says, they were told, “It’s done—you signed your name and you have to pay.”

AmeriCredit spokesman John Hoffmann said the lender could not respond to specific customer complaints. But, he said, “The company doesn’t condone or accept abusive treatment of its customers. . . . I would encourage any customer who feels that they have been treated inappropriately to contact the company and let us know.”

None of AmeriCredit’s legal problems has prevented it from becoming a leader in the burgeoning “subprime” auto-loan market, which charges high rates to consumers with damaged credit or humble incomes. Subprime auto lending has grown rapidly, thanks in part to Citigroup, Capital One, Household, and other big-name financial institutions that have pushed their way into the market. The Federal Reserve estimates the market for subprime auto loans has more than quadrupled in just a decade, swelling to $65 billion a year. Some industry leaders believe the market is even bigger than the Fed reckons—$125 billion or more a year.

Chain Gang

A New Breed of Corporate Entrepreneurs Is Changing the Used-Car Business

The used-car marketplace now includes publicly traded companies such as Bentonville, Ark.-based America’s Car-Mart. Like its hometown neighbor, Wal-Mart, it focuses mainly on small cities and rural locales. The logic, its chief executive says, is simple: “If there’s a default, it’s a lot easier to find collateral in Conway, Ark., than in Dallas, Texas.” By charging a typical interest rate of 19 percent, America’s Car-Mart and its 65-plus franchises do well enough that Investor’s Business Daily lauded the company’s stock as the top performer among 28 auto sales and auto parts stocks ranked by the business publication.

Another used-car chain, Drive Time, was launched under the name Ugly Duckling in 1991 by Ernest Garcia II, a Phoenix developer who had been convicted of fraud for his part in Charles Keating’s Lincoln Savings & Loan scandal. By 2000, the chain’s sales approached a half billion dollars. Now it claims 76 locations across the Sun Belt, including 32 in Texas, Georgia, Florida, and Virginia.

Given the car industry’s predilections, all consumers—rich or poor, black or white, good credit or bad—should be wary when they step onto an automobile lot. But an examination of lawsuits and academic studies from around the country provides evidence that the worst abuses are most frequently targeted at African American, Hispanic, elderly, working class, or credit-impaired customers. Many dealers and lenders perceive these consumers as having fewer options, less financial experience, and a diminished sense of marketplace entitlement, thus making them more likely to be desperate or susceptible when it comes time to close the deal.

And the deals that are being closed on many car lots are not pretty ones. Subprime borrowers often pay interest rates between 17 and 25 percent on auto loans, compared to single-digit rates for borrowers with good credit and strong bargaining skills. This is no small matter: the difference between paying a competitive rate or a subprime one can mean $3,000, $4,000 or more in extra finance charges on a five-year, $10,000 used-car loan. Disadvantaged customers are also more likely to be targeted by dealers and lenders for an array of overpriced extras: credit insurance, roadside assistance plans, extended warranties, service contracts.

In step with the Wall Street-fueled growth of the subprime market has come the dominance of what Ward’s Dealer Business magazine calls “megadealer” groups—vast, often publicly traded chains of dealerships that sway market trends and help set the tone for ground-level sales practices. The nation’s three largest megachains—AutoNation, United Auto Group and Sonic Automotive—posted $34 billion in sales last year, almost one-third of combined sales for Ward’s top 100 dealer list. The big three’s growth and profits have been accompanied by lawsuits, government investigations, even criminal prosecutions. AutoNation, United Auto, and Sonic have been dogged by allegations that they use deceptive practices to overcharge customers on financing, insurance, and other items.

For their part, dealers and lenders say any abuses are isolated incidents, not symptoms of systematic misbehavior. GMAC and other auto lenders, for example, have vigorously denied that they take advantage of minority borrowers. GMAC says it “adheres to a zero-tolerance policy on racial discrimination.”

Although GMAC has agreed to a tentative settlement of the nationwide class action over its loan-markup policies, it has denied wrongdoing in the case and says it “adheres to a zero-tolerance policy on racial discrimination.”

Securing Abuse

AmeriCredit and other auto financiers have had a bumpy ride as the recent economic downturn has depressed used-car values, and as too-rapid growth in sub-prime lending has forced inevitable market corrections. After posting after-tax profits of $314.5 million in fiscal 2002, AmeriCredit’s net income plummeted to $21.2 million in fiscal 2003.

Still, many companies are finding the business profitable, and subprime auto financing continues to attract investor interest and support from the highest echelons of American commerce. Over the past decade, Wall Street has claimed a piece of the action—and fueled the market’s growth—by trading securities backed by income streams from humble and sometimes fraud-tainted used-car loans.

The lenders assemble these loans into pools, and investors buy securities tied to the pools’ performance. AmeriCredit “securitized” more than $15 billion worth of loan-backed securities in 2001-2002, number one by far among subprime lenders and number three overall behind Ford Credit and GMAC.

All this market power makes a difference. The flow of money up and down the financial food chain influences conduct at the bottom. It is now the lenders and their Wall Street backers who drive many of the dubious practices at local car lots. The lenders use financial incentives, computerized underwriting, and well-crafted training programs to teach dealers and salespeople how to do things their way.

Tom Domonoske, a former Duke law professor who is now a consumer attorney in Harrisonburg, Va., says lenders tutor dealer finance managers how to write contracts that pack in as much plunder as possible while appearing on their face to be above-board—and thus safe gambles for pension-fund managers and other investors who buy loan-backed securities.

“The securitization is determining what’s happening between the customer and the finance manager, because the loans are being made to look a certain way so they can be sold and packaged,” Domonoske says. “Each individual car transaction is really part of a process of manufacturing a credit contract, and the credit contract is a step in the process of producing a pool of credit contracts” that are sold as securities.

John Anglim, a securities expert with Standard & Poor’s, counters that there’s a strong incentive for lenders to make sure loan originations are aboveboard—if borrowers don’t pay their loans, the loan pools suffer, and the lenders will in turn suffer financially. “If there are shady things going on,” Anglim says, “I would argue that it’s at the dealership level.”

Car Talk

Here’s a glossary of some of the secret lingo—sometimes vulgar, often instructive—that many car dealerships use to describe how they conduct business.

GRAPES easy marks; customers readily persuaded to pay more than they should. A salesperson will “squeeze the juice” out of them by selling them cheaper cars at prices usually attached to more expensive cars.

LAY-DOWNS same as “grapes”; customers who will “lay down” for whatever the dealership offers.

ROACHES customers with bad credit; typically said to “come out at night” because they’re embarrassed—and are thus likely to be easily manipulated.

ETHER “natural” high a customer gets when inhaling a new car’s interior; a term originating from rumors the chemical was used in treating the carpets, as a way of making the customer lightheaded.

STEP-SELL a softening-up approach; the salesperson purposely pushes a car the customer won’t want, in order to get rid of the customer’s “No’s.” The rationale is that most people want to feel they’ve shopped around before they say “Yes.”

DROP YOUR PANTS salespeople who show the customer the invoice are said to have “dropped their pants.”

BACK-END the point in the deal when the dealership sells high-priced add-ons, such as alarms, CD players, spoilers, paint protectants, and underbody sealants. The excess profit they produce is called “gravy.”

USED CAR FACTORY mythical place the customer thinks exists to produce the exact color, quality, and features they want in a used car. A frustrated salesman will say, “Sorry, the used car factory is closed.”

TAIL-LIGHT WARRANTY a warranty that’s worthless once the customer’s tail lights are out of sight.

Domonoske says lenders often hide the pools’ shaky origins by convincing customers with good credit that they have bad credit and should pay higher rates—and by putting the screws to less-well-off customers who are struggling to keep up. “The pool will do well enough if the customer can be coerced to pay,” he says. “What we’re seeing is a tremendous rise in debt collection abuses. People are being squeezed to pay debts they cannot pay for loans that in many cases should never have been made.”

Jo Anne Wilson, an AmeriCredit customer in Kentucky, wrote the state attorney general’s office claiming the company had violated her trust and her rights, first by gouging her on her loan and then by haranguing her when she fell behind. Her $10,145 car loan came with a 19.95 annual percentage rate and an $895 service contract. Later, she said, AmeriCredit’s collectors harassed her, along with her parents, her soon-to-be ex-brother-in-law, even an elderly neighbor who is sick and disabled. She told AmeriCredit to contact her lawyer, Wilson said, but “they told me I had no right to an attorney.”

“If you go through your records, you will find we have already paid one vehicle off through you,” Wilson wrote the lender. “You need to take that into consideration as well. But all you all know to do is sit behind a desk where it’s comfortable and harass people.”

AmeriCredit replied that it had reviewed Wilson’s complaint and determined it had handled her account properly. “Please be assured,” the company wrote the attorney general, “it is not the policy of AmeriCredit to ‘harass’ its customers or contacts.”

Human Nature

Salesman, wholesaler, used-car manager, sales manager, finance manager: Duane Overholt had done it all in 24 years in the business. In that time, he says, he’d also done things he hadn’t been proud of, thanks to financial incentives that encouraged him “to use unethical and sometimes illegal practices to scam consumers out of hundreds of thousands of dollars.” Overholt claims that at Clearwater Mitsubishi, one of Sonic Automotive’s Florida stores, his boss exhorted him to “crush” customers by packing overpriced extras into their deals.

He’d had enough. “You simply make a decision to stand up and tell the truth—it was wrong and I was wrong,” he told Tampa’s WFLA-TV. He also laid out his claims in statements to state and federal authorities and in a wrongful dismissal lawsuit against Sonic.

His inside information helped fuel a Florida attorney general’s probe and an onslaught of litigation targeted at Sonic, the Charlotte-based auto behemoth that vies each year with United Auto Group for the No. 2 spot on Ward’s megadealer list. Lawsuits alleged Sonic executives supervised a scheme to falsify credit applications, sell overpriced warranties, and forge customers’ signatures. One customer, Mac Williams Jr., told WFLA, “On one of the documents they had even misspelled my name, which sort of upset me. If you’re gonna forge my name, at least spell it right.”

A class action lawsuit involving as many as 10,000 customers alleges that overcharges and other misdeeds were standard procedures—a pattern of conduct perpetrated by local salespeople and managers but choreographed by high-level corporate officials. The suit claims that executives controlled lower-level employees with top-down specificity, fostering predatory conduct through a system of bonuses and kickbacks coupled with the threat of firing, demotion, or transfer for managers who didn’t comply.

The suit says executives demanded weekly “penetration reports” on sales of insurance add-ons, and set a goal that finance managers pack on $800 of “back-end” products such as anti-theft insurance onto each sale—a benchmark the lawsuit says Sonic executives knew “could only be achieved through fraudulent sales practices.”

When Enrique and Virginia Galura purchased a new Toyota Spyder, the suits says, Sonic’s Clearwater Toyota charged them $562 for an anti-theft insurance policy whose real price was $30. The $562 was not disclosed on the insurance form, the suit says, but was handwritten in after the couple drove off the lot. Another Sonic customer, Ana Diaz-Albertini of Palm Harbor, Fla., was charged $1,140 for the insurance—which paid only $1,000 in the event of theft and damage and $2,500 in the event of theft and total loss.

A lawyer for the company says Sonic is “steadfastly committed to treating its customers fairly and honestly.” Sonic officials said they investigated allegations of misconduct at Clearwater Mitsubishi and found just one infraction, which they responded to by firing the employee in question.

The complaints against Sonic aren’t unique among the nation’s largest auto chains. The number one megadealer, Fort Lauderdale, Fla.-headquartered AutoNation, agreed to pay more than $5 million to settle a private class action and a California Department of Motor Vehicles lawsuit accusing its El Monte, Calif., Chevrolet location of defrauding more than 1,500 customers through a variety of sharp practices, such as selling used cars as new, forging customer signatures, and charging for security systems that were never installed. Seven employees were convicted of crimes in the case.

In Florida, lawsuits have accused the chain of still more abuses, such as engaging in a “spot delivery” scheme, in which customers drive new purchases home thinking their deals are done, only to be informed that their financing wasn’t approved and they must redo the deals on less-advantageous terms.

AutoNation has denied wrongdoing, blaming any violations on a handful of unprincipled employees. “You’ve got human beings who are going to act like human beings act,” a spokesman said after the California DMV sued. “Some guys break the rules and these guys did.”

The Price of Confession

By Stephanie Mencimer, an investigative reporter based in Washington, D.C.

When Don Foss opened his first used-car lot in 1967, he became famous in Detroit for wearing a clown suit on late night TV ads. But Foss was no ordinary car dealer. He quickly realized that easy financing was the ticket to getting people on to his lot, and the system of dealer financing he subsequently developed helped revolutionize the used-car market by finding lucrative revenue streams in areas traditional banks had avoided—people with bad credit and old cars.

Foss immortalized his sales genius in copyrighted training videos developed for Credit Acceptance Corporation-affiliated dealers. The low-budget productions feature a CAC executive standing in a classroom full of car dealers, exhorting them, “People who have bad credit are just good people who had something bad happen to them.”

The videos preach psychotherapy as much as smart sales techniques. To reassure customers wary of yet another credit rejection, the videos and training manuals suggest using the “CAR” system: Confession, Absolution, Redemption. Play the confessor, the tapes say: “Listen. Let the customer get their problems off their chest.” Dealers are encouraged to nod and coo while customers pour forth tales of woe about bankruptcy, divorce, and unemployment. Once the customer has “confessed” his bad-credit sins, the dealer gives him “absolution”—the good news that he can in fact buy a car. “Redemption” comes when the car is delivered. Central to the success of the program is the dealers’ understanding that these customers have no other options. “They will buy just because you have something they can get,” the tapes say.

The technique has helped turn the old used-car dealer into a finance salesman. Indeed, many independent used-car dealers don’t really sell cars anymore. “The worst thing you can do is sell cars,” CAC teaches dealers in its videos. “We don’t sell cars. We sell financing.”

Step into one of these dealerships and you won’t hear about state-of-the-art fuel injection or the safety benefits of an SUV. Test drives are rarely offered. Pressure for the down payment can be intense, and often comes with instructions that a down payment is needed before a credit application can be processed to prove a borrower “legit.” That’s because CAC training materials advise dealers to get money from people before they even test-drive a car. “Simply hold out your hand and ask for it,” the tapes say. “Usually, the customer will give you the money the first time.”

The test drive, according to CAC training materials, is mainly to protect the dealer against lawsuits. When offering a test drive, CAC trainers remind, “It is important to keep in mind we sell financing, not cars. Present the car by showing the customer where things are, but don’t get involved in selling the features. The customer will likely have questions about the car. Return to the financing answer when responding to the questions.”

Hooking a customer on a sweet Jeep Cherokee or another top-shelf vehicle is a risky proposition for a finance salesman, according to CAC training tapes, because in all likelihood, the customer will only qualify for a Geo Metro. “Selling the car will make it harder to re-select [a less expensive car],” the tapes explain. If the customer is disappointed with the Metro, CAC urges dealers to remind him that financing will help “re-establish” his credit, at which point he can come back and get a better car. “Always come back to the financing,” the tapes exhort.

United Auto Group, meanwhile, has had legal problems of its own. In Little Rock, Ark., consumer attorneys have accused UAG of charging illegal “document preparation fees”; the attorneys hope to expand the case to include tens of thousands of transactions. In Memphis, Tenn., a lawsuit accuses UAG’s Covington Pike Toyota of preying on women and minorities by secretly marking up their finance charges beyond the interest rates quoted by lenders. In May, a state judge approved class action status for the case, writing that the so-called “dealer-reserve fee” results “in higher interest rates, higher monthly payments, and higher total finance charges to the customer and is not disclosed to the customer at any time.”

Target Practice

The dealer-reserve scam works this way: The dealer takes the customer’s application, submits it to a lender, and the lender comes back with its “buy rate.” For someone with a mediocre credit history, the lender’s rate might be, for example, 9 percent. But the dealership doesn’t tell the customer that. Instead, it quotes a much higher rate—say 12 percent.

The difference is the finance “markup.” On a $14,000 used-car loan, hiking the rate from 9 to 12 could cost the consumer more than $1,200. Critics call this a kickback, the lenders’ way of enticing dealers to steer loans in their direction. As many as 20 class actions over the markup issue, involving millions of borrowers, are percolating around the country.

Michael Terry, a Nashville attorney who has helped lead the legal attack, says white consumers get fleeced, too, but it is Latinos and African Americans who are most likely to be gouged. Victims include black lawyers and doctors. “When they get out of the car with a black face . . . they become a target,” Terry says. “We’ve talked to dealers and they tell us it’s true. They joke about them having a target on their backs.”

A study by one of Terry’s expert witnesses looked at 1.5 million GMAC loan transactions and found 53.4 percent of blacks paid markups, compared to just over 28 percent of whites. The disparity couldn’t be explained by differences in creditworthiness. On average, African Americans paid more than two times the markup whites paid—with a markup of $656 for blacks and $242 for whites. The largest spread was in Tennessee, where whites paid an average markup of $317 and blacks paid $929.

Terry’s experts found similar patterns in a study of 300,000-plus Nissan Motor Acceptance Corporation loans. Black Nissan borrowers paid an average markup of $970, compared to $462 for whites. Nissan called that statistical analysis “junk science.” In February, however, the company agreed to pay a modest $7.6 million settlement covering attorneys’ fees, contributions to consumer education, and $60,000 divided among 10 main plaintiffs. It also promised to make 675,000 no-markup loans to Latino and African-American car buyers.

The settlement isn’t the end of Nissan’s legal tribulations, however. In July a new class action filed in California accuses the company of engaging in an elaborate scheme that targets low-income car buyers for overpriced deals and quick repossessions.

Consumer attorneys say the practice—called “churning”—is not uncommon. TranSouth Financial Corp., a Citigroup subsidiary, and Charlie Falk Auto, a chain of used-car dealers in Virginia, agreed to pay nearly $17 million to settle a class action accusing them of working hand-in-hand on a churning scheme.

The California lawsuit claims Nissan makes loans to vulnerable customers knowing most can’t keep up the payments, then repossesses the vehicles and leaves the buyers stuck with no car, huge bills, and ruined credit. To make matters worse, the suit claims, Nissan dealers buy the cars cheap at auctions illegally closed to the public, then restart the process by selling them again.

Nissan calls the class action “a frivolous suit” and promises to mount a vigorous defense.

The named plaintiff in the case, Sonia Barrera of Los Angeles, owned her 2002 Sentra for less than a year before it was repossessed. Nissan sent her a bill for almost $13,000—a figure that represented the $19,120 purchase price minus the $6,400 Nissan had pocketed for the car at auction. “Sonia Barrera has a $13,000 bill for a car she no longer has,” her attorney, Henry Bushkin, told the Los Angeles Times. Even “if she could pay this, it would take her the rest of her life.”

Image and Reality

Back when Mercury Finance was riding high, CEO John Brincat explained how his company was helping to clean up the car business’s image—and doing so well it was reporting a stunning 9 percent return on assets. “There’s this image of a gravel lot on the wrong side of town where you drive by in the morning and see five cars, three with their hoods up and battery charges on and one getting its tires pumped up,” Brincat said. “We do most of our business with franchised new-car dealers. These aren’t skid row types.”

It’s an effective business model: Buy into an industry plagued with a spotty reputation, consolidate its fragmented parts and polish its image with sophisticated marketing and a gloss of corporate respectability. Disney did it with the carnival business. Texas-based Cash America did it with pawnshops.

Subprime auto financiers and megadealers such as AutoNation have been trying to do the same with the car business. They’ve tried to change the industry’s image from a hindrance to an asset. The well-capitalized new guard plays off the old reputation by selling the public on the idea that it’s a different breed: well-organized, well-scrubbed, reputable.

As Mercury Finance was making its climb, other companies were following similar scripts in an effort to tap into the subprime market. Executives at Cash America decided it was time for a new wrinkle in American commerce: a publicly traded chain of used-car lots. In 1989, their brainchild, Urcarco, raised $43 million in startup funds. The company parodied its unwashed competitors with a TV spot featuring a cowboy-hatted salesman named “Bubba.” When he slapped the hood of a car, the fender fell off. Urcarco’s sales soon hit $38 million a year.

Michigan-based Credit Acceptance Corp., meanwhile, was helping to remake the auto-loan market by showing there was money to be made financing older, low-end cars. The company flourished because of its aggressive collections program and because it offered its partners, the dealers, detailed instructions on how to sell to folks in financial straits—including the recommendation that salespeople demand a down payment even before the customer gets a chance to test-drive the car (see “The Price of Confession”). After it went public in 1992, Credit Acceptance’s stock zoomed so high its founder, Donald Foss, found himself on Forbes Magazine’s list of the country’s richest men, with his stake in the company valued at over half a billion dollars.

All three of these companies—Urcarco, Mercury Finance, and Credit Acceptance—reveled in the investor buzz that accompanied their dizzying stock climbs. But as with many success stories, there were darker chapters. Investors would learn what many borrowers were already discovering first-hand: combining used-car sales and subprime financing can produce a combustible mixture.

In the early 1990s Urcarco’s loan defaults suddenly skyrocketed, its repossession rate hit 50 percent, and profits turned into red ink. Company officials blamed overexpansion and recession, but there was evidence other problems also contributed to the customer revolt. A class action accused the company of gouging consumers with hidden charges. One ex-employee told the Dallas Morning News: “I did a lot of deals where I was told, ‘I don’t care what you do, but make it look like that guy can afford the car.’ They try to act totally professional, but if you sit behind closed doors at the lot, you find out it’s not.”

A jury in Alabama slammed Mercury with a $50 million verdict after hearing testimony that the company had slipped a $1,000 hidden charge into the financing package for a $3,000 used car. In 1997, the FBI raided Mercury’s headquarters and Brincat resigned amid revelations that the company had inflated its profit statements.

Credit Acceptance came under attack from lawsuits accusing the company of abusing late-paying borrowers, squeezing out questionable fees and interest, and piling on steep charges once customers fell behind. A group of shareholders filed a securities-fraud suit, accusing Credit Acceptance and one of its affiliate dealers, Larry Lee’s Auto Centers, of selling junk cars and soliciting down payments that exceeded what the dealer paid for the vehicles. Before the suit was settled, the former president of the dealership chain testified he’d warned Credit Acceptance about the quality of cars they were selling and financing: “You sell cars that have bad transmissions, people ain’t going to pay for them,” and loan defaults will start piling up.

Mercury Finance emerged from bankruptcy protection under the name MFN Financial Corp. Credit Acceptance has weathered stock declines and hard times in the used-car business to reemerge as a profitable company, posting revenues of $154.3 million and after-tax profits of $29.7 million last year.

And Urcarco? It survived its troubles, too, by abandoning its car lots and mutating into a different sort of animal: a subprime auto financier. It sold off its inventory and announced a new name for a new direction: AmeriCredit.

Walked Into It

AmeriCredit has become, along with Household Finance, a dominating force in the subprime auto market. Forbes praised the company’s turn-around strategy, which saved it from near-extinction after the Urcarco debacle. Fortune named it one of the best companies to work for in America. AmeriCredit says it has grown by honoring a commitment to “deliver what we promise with loyalty to execution.” AmeriCredit’s Web site quotes two customers who say: “I don’t know why we never thought of doing this before because it made everything so much easier! Thank you for helping us to make this so painless!”

The ease of the loan process—how painlessly customers are persuaded to sign up for AmeriCredit loans—was at issue in the lawsuit against the company in West Virginia. Jeffrey Preece, the former special finance manager at Crown Pontiac, said it was easy for him and his co-worker, Kenny Burgess, to get customers to sign up for dicey loan deals, using old-fashioned salesmanship and the system designed by AmeriCredit’s Charleston office: “We walked them right into it. . . . Most of the people you don’t have to persuade. They’re desperate. We took advantage of that.”

In pre-trial testimony the manager of AmeriCredit’s Charleston office insisted that fake down payments weren’t a regular item in loan deals, and were never tolerated by AmeriCredit. “If a contract shows a down payment, I assume there’s a down payment there,” the manager, Bob Bumpus, testified. As for the moniker “Kenny Burgess Cash,” Bumpus said it was a comment “made in jest” after a single instance in which a Burgess deal had turned out to include a nonexistent down payment.

AmeriCredit’s attorneys suggested no customers were hurt, even if there’d been some creative use of down payments; customers got what they wanted—a car. And besides, the attorneys said, they had ample opportunity to grasp the details of the contracts.

As one attorney prodded Preece during a deposition: “The information was there, available to them to see what was going on, correct?”

“Not really,” Preece replied. “Because, I mean, if you showed me an engineer’s design of the Space Shuttle, it’s right there in front of me, but I don’t know what that means. I’m not an engineer. Well, these people weren’t finance people and they weren’t car people.”

The people who understood how it worked, Preece said, were the car and finance people; the scheme couldn’t have worked without the participation of multiple players at the dealership and at AmeriCredit.

In the brave new world of car financing, it’s less and less possible for individual dealers and salespeople to act on their own. Top-down economics and management are paving over gravel lots and splashing paint and fresh logos onto showrooms—and showing how to put a new and profitable spin on the business’s age-old rituals of artifice and exploitation.

“Everybody is trying to say: ‘It wasn’t me. It wasn’t me,”’ Preece said. “Yes it was. It was all of us. Collectively as a group, we all knew. We all did it and we’re all guilty.”

Dealer Scams

Examples of “Top 10 Car Dealer Scams,” an annual listing from CarBuyingTips.com

The “VIN# Window Etching” Scam.

How it works: Dealers charge hundreds of dollars for etching your new car’s window with the vehicle identification number (often even when they say it’s “free”).

How to avoid getting ripped-off:

Demand it be removed from the contract. If they say it’s free, ask them to put it in writing. If they say it’s already on the car, don’t buy the car. If you do want the etching, you can buy kits to do it yourself, much cheaper, at such sites as CarEtch.com.

The “Spot Delivery” Scam.

How it works: You trade in your old vehicle. The finance manager tells you that you got a good interest rate. You drive home with your new car. Then the dealership calls and says your loan fell through. They demand more cash and higher monthly payments.

How to avoid getting ripped-off: Don’t finance through a dealer if you have bad credit.

The “Lie to the Customer About Their Credit Score” Scam.

How it works: The finance manager displays a “concerned” look, telling you there’s a problem with your credit report and you don’t qualify for a low rate.

How to avoid getting ripped-off: No salesperson should know more about your credit than you do. Know your score coming in.

Tags

Michael Hudson

Mike Hudson is co-author of Merchants of Misery: How Corporate America Profits from Poverty (Common Courage Press), and is a frequent contributor to Southern Exposure. (1998)

Mike Hudson, co-editor of the award-winning Southern Exposure special issue, “Poverty, Inc.,” is editor of a new book, Merchants of Misery: How Corporate America Profits from Poverty, published this spring by Common Courage Press (Box 702, Monroe, ME 04951; 800-497-3207). (1996)