This article first appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 31 No. 2, "Banking on Misery." Find more from that issue here.

When it’s Friday, the rush starts early at Ace Cash Express Inc., a tidy storefront along a busy highway in a working-class and minority section of Arlington, Va., an otherwise mostly affluent Washington, D.C., suburb.

By 9:15 a.m., just after the store lights up its welcoming green neon sign, three people are already lined up at the bulletproof cashiers’ window, paycheck stubs in hand. They are applying for short-term, high-rate cash advances known as payday loans—money they hope will tide them over until their next paycheck arrives.

It’s quick and easy for customers to dash in and out. And it’s a regular routine. Many say they work at a nearby Head Start but don’t earn enough money at the federally-funded early childhood development program to make ends meet.

“Just more bills,” one woman says, explaining her rationale for yet another payday loan as she counts out her money from the cashier.

For her, and for the tens of thousands of other regular payday loan customers, a transaction once considered on the fringes of the financial system now has become a part of everyday life.

Fringe banking—an umbrella term that covers payday lending, check cashing, prepaid phones and cards, bill paying services, and more—no longer exists on the fringes. In the decade since these non-mainstream financial services began to gain a foothold in people’s lives, their image has changed from seedy or unsavory to ordinary and accepted, if not outright embraced.

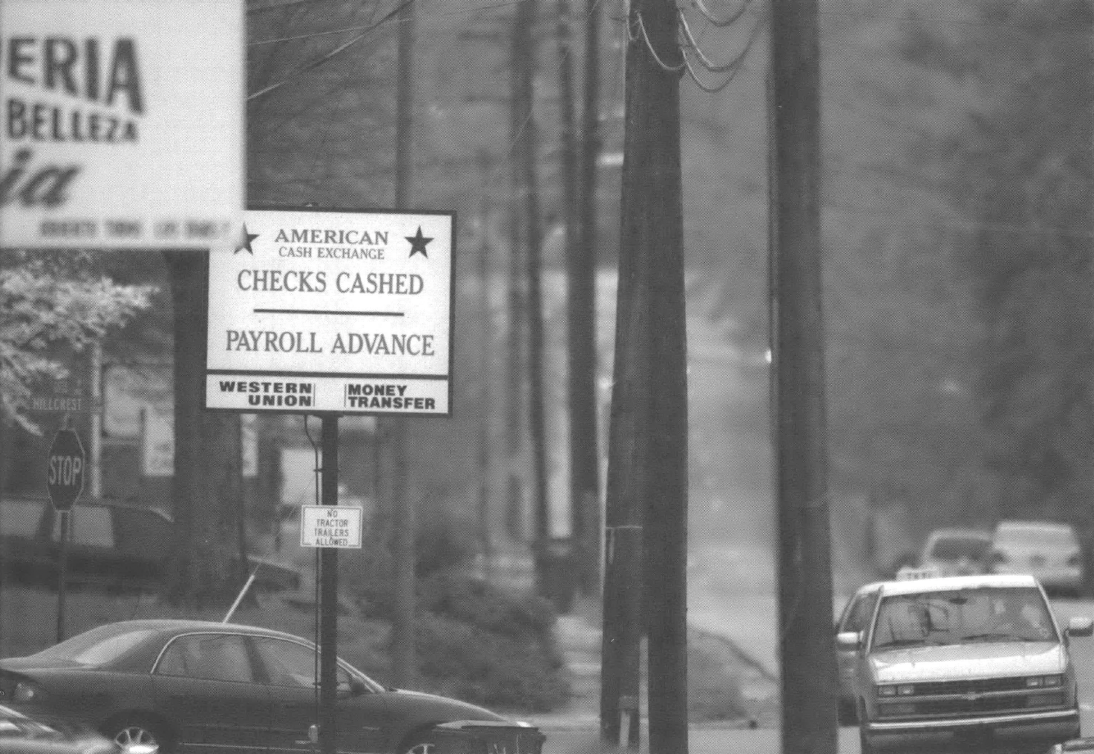

Take a look around. Fringe banking thrives in your neighborhood, at the 7-Eleven, where you can cash your paycheck or make a money transfer on an ATM-like machine. Going shopping in the suburbs? Check out the pawnshop, right next to the Chili’s restaurant. Or cruise a typical suburban highway like Columbia Pike in South Arlington, which features a half-dozen check cashers and payday loan stores interspersed among the dry cleaners, pharmacies, grocery stores, and ethnic takeouts.

In California, New York, and Baltimore, credit unions and even banks work side-by side with check cashers. And soon to come to a Wal-Mart near you: an in-store check-cashing service.

Fringe banking operations have also grown from single-service storefronts into more diverse businesses, allowing people to handle all their financial needs in one spot, for a fee, of course. Send a fax. Pay the phone bill. Buy a bus pass. Get a tax refund. Take out a loan. Cash a check. All without going to the bank.

“These places have now have become financial supermarkets,” said Jean Ann Fox, Director of Consumer Protection for the Consumer Federation of America.

And their growth has exploded. Since 1993, the number of check cashing stores has increased from 4,000 to over 16,000, research by John Caskey, an economist and Swarthmore College professor, shows. Payday lending has grown even more rapidly. So rare before 1995 that no state regulators kept data on them, payday lenders now number 25,000, according to industry research. And last year, these lenders made between 95 and 100 million loans, generating $4.3 billion in fee revenues.

One constant has been the cost—financial transactions with dizzyingly high rates. Payday loans of 400 percent or more. Pawnshop loans amounting to 240 percent. Check cashing fees amounting to $25 per $100.

Because of these kinds of profits, people the banks wouldn’t touch a decade ago have grown into hot commodities. To critics, this has furthered a worsening financial divide between those who can afford credit at decent prices and those who can’t. And it has underscored the continuing plight of low-wage workers who don’t earn enough to cover their basic needs.

Industry defenders reject that notion. They say that people consistently need short-term loans and other financial services that they can’t get from a bank. Consumer advocates who fight fringe banking, they say, simply are out of touch with how working class people live.

“Banks are not customer-friendly,” said Paul Hauser, president of The Check Cashing Store, the largest chain of check cashers and payday lenders in South Florida. “And besides, where else does the person go who needs $100 for their broken-down car when they don’t have a rich Uncle Harry to turn to?”

In increasing numbers, they’ve been turning to payday lenders.

Consider ACE Cash Express Inc., a publicly traded company located in Irving, Tex. In 1998, payday lending accounted for 10 percent of its overall revenues, with the rest provided by check cashing. Total revenue per store was $154,000.

By 2002, 32 percent of ACE’s revenues came from payday lending, and total revenue per store had climbed to $230,000, Caskey reported.

“There is a real need in the marketplace for short-term, immediate credit,” said Eric Norrington, an ACE spokesman.

ACE is among a handful of major chains that dominate the industry, most located in the South. How do they make their money? A customer brings a personal check to a lender. The lender, in turn, agrees to hold it for two weeks before depositing it. The lender advances the customer the amount of the check, minus the fees, usually $15 to $25 for every $100. So the customer seeking a two-week loan on a $200 check pays $30, or 390 percent interest.

Studies of the industry by regulators in Indiana, Illinois, Wisconsin, and North Carolina have found that payday lenders make even more money from repeat customers who pay another fee to take out a new loan as soon as the old one is paid.

What’s somewhat surprising about borrowers is that they are not completely cut off from the traditional financial world. A typical customer must have a banking account. Most of them, research shows, earn between $15,000 and $60,000. Half own credit cards. Most are under 40, with high school educations or more, and have kids at home. More than half are women.

Conversations with customers at the ACE store in suburban Virginia revealed a range of reasons for using the payday lender, from short-term problems like a high utility bill to repeat customers in a financial bind they hope to climb out of—someday.

Wendell Lewis, 49, said he finds himself a regular customer because of his continual struggle to meet his $800 a month child support obligations. Lewis, a transportation supervisor at Head Start, earns about $30,000 a year, a salary at the low end in the affluent northern Virginia area.

Lewis took out payday loans for about three months, stopped, and then returned. This time it’s because he needed a car. With past credit problems, the interest rate on his loan would have been about 18 percent, so Lewis used his last $2,800 in savings to cut that cost. The move lowered his monthly payment from $570 to $370, but left him in a deficit when it came to covering his bills.

Savvy enough to cut his subprime loan rate, Lewis said he’s well aware of the high interest rate on his payday loan. But he doesn’t feel he has any other choice.

“Well, it’s not great. But you can get right in here and get right out,” Lewis said. “And hopefully it’s just one more time that I have to do this.”

For Frances Jackson, it was a harsh winter that sent her to the payday lender. Jackson, 37, the sole supporter of two children, also works at Head Start, earning about $30,000 a year. She gets some government help with her $1,300 rent payment. But a $349 electric bill sent her over the edge.

“The banks just tell you your credit is no good,” Jackson said. “If I don’t come here the utilities will just cut me off.”

Not everyone comes to ACE for loans. Dashing in and out, a young construction worker quickly cashed his paycheck. It was quicker to come to ACE than to stand in line at the bank, he said, so the convenience outweighed the fees.

But others consider a payday lender their last resort. A private security guard, who declined to give her name because she is looking for a job, was recently laid off from a government position. Now, earning half her old salary, she goes to the payday lender to make it through the last 26 payments on the car she bought when she made more money. If only she could get a 30-day loan, she sighed, clutching a file of her resumes in her hand, she might be able to make it.

Payday lenders try hard to make their stores welcoming to customers like her. The Arlington ACE employs a smiling bilingual cashier who seems to know many of the people coming in. Stacks of Latino yellow pages and a free Latino weekly newspaper are displayed. ACE has a valued customer program, with discounts for people who cash checks frequently.

The industry is constantly trying to improve its image, said Rick Lyke, spokesman for a trade group representing fringe bankers. Members are moving away from the term “payday loans,” referring instead to such services as “deferred deposits.” Advances in technology also mean new fringe banking products always are in the works, he said.

Check cashers and payday lenders also continue to move even more into the mainstream by offering such services as state motor vehicle registration, Lyke said. And more businesses are diving into the market.

But consumer advocates are fighting back.

Some 17 states do not authorize payday lending, but companies operate in some by partnering with state-chartered banks. These rent-a-bank arrangements allow payday lenders to bypass state usury laws and other regulations.

Regulators in some states are challenging these arrangements and others are trying to restrict fees or outlaw rollovers. Should opponents win the battle, Caskey believes payday lenders will have to withdraw from some 30 states, a severe blow to the industry.

But nothing will put a final stop to payday lending until either Congress steps in or the detrimental consequences to consumers become more apparent to the public, said Consumer Federation’s Fox. She predicts many more battles ahead.

“This is going to be a long, drawn-out fight,” she said.

Payday Loans:

The Trap Payday Lending Traps Borrowers in a Cycle of Debt. While payday loan rollovers were illegal under former North Carolina law, lenders use back-to-back transactions to accomplish an effective rollover at the same high cost to borrowers. Borrowers who cannot repay their entire $300 loan in two weeks pay $45 in fees every two weeks to “renew” the loan. These high renewal fees make it less Borrower Lender likely that the borrower will have the funds to repay the $300 loan. Borrowers continue to pay fees and still owe the $300. This is the debt cycle.

Example borrower: The average North Carolina borrower takes out eight payday loans from a single payday lender. In the example below, the borrower spends 14 weeks in the debt cycle (original loan plus seven renewals). Receiving only $255 cash, the borrower must repay $615 to close out the loan ($360 in fees plus the original $255 cash received).

Fees paid often exceed the amount of cash received by a borrower. When a borrower does six repeat loans they have paid more in fees than they received in cash. This cycle of debt can go on for years, with the borrower paying $45 every two weeks without receiving “new money.”

Tags

Mary Kane

Mary Kane is a freelance business journalist in Arlington, Va. She covered finance for Newhouse News Service in Washington for 11 years. (2003)