This article first appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 31 No. 2, "Banking on Misery." Find more from that issue here.

They said a prayer in a parking lot in Memphis and clambered into four rented vans. They drove the length of Tennessee, traveling all night, watching the sun rise over Northern Virginia’s commuter lanes and pushing on up the New Jersey Turnpike. It was a grueling, almost non-stop journey, but they were determined to reach their destination: New York City and Citigroup’s annual shareholders’ meeting.

Eddie Smith, a laid-off truck driver from Arlington, Term., drove the entire 20 hours, piloting the last van in the Memphis convoy. He and his wife Trudy had been struggling to make their payments on a CitiFinancial loan secured against their double-wide manufactured home. It’s not a mansion, but it has a white picket fence around its well-kept yard, and they don’t want to lose it.

“I worked my tail off for years and years just to have a box to live in, and eventually they’re going to take it from us,” Eddie Smith said as he wheeled the van northward. That’s why the Smiths were heading to New York—to try and get someone to listen to their complaints that CitiFinancial has misled and mistreated them.

And they weren’t alone. Resolute vanloads of people came from Charlotte, Tampa, Columbia, S.C., Mobile, Ala., and many other places, a contingent of about 50 borrowers and 250 family members and activists from across the Northeast, Midwest, and South.

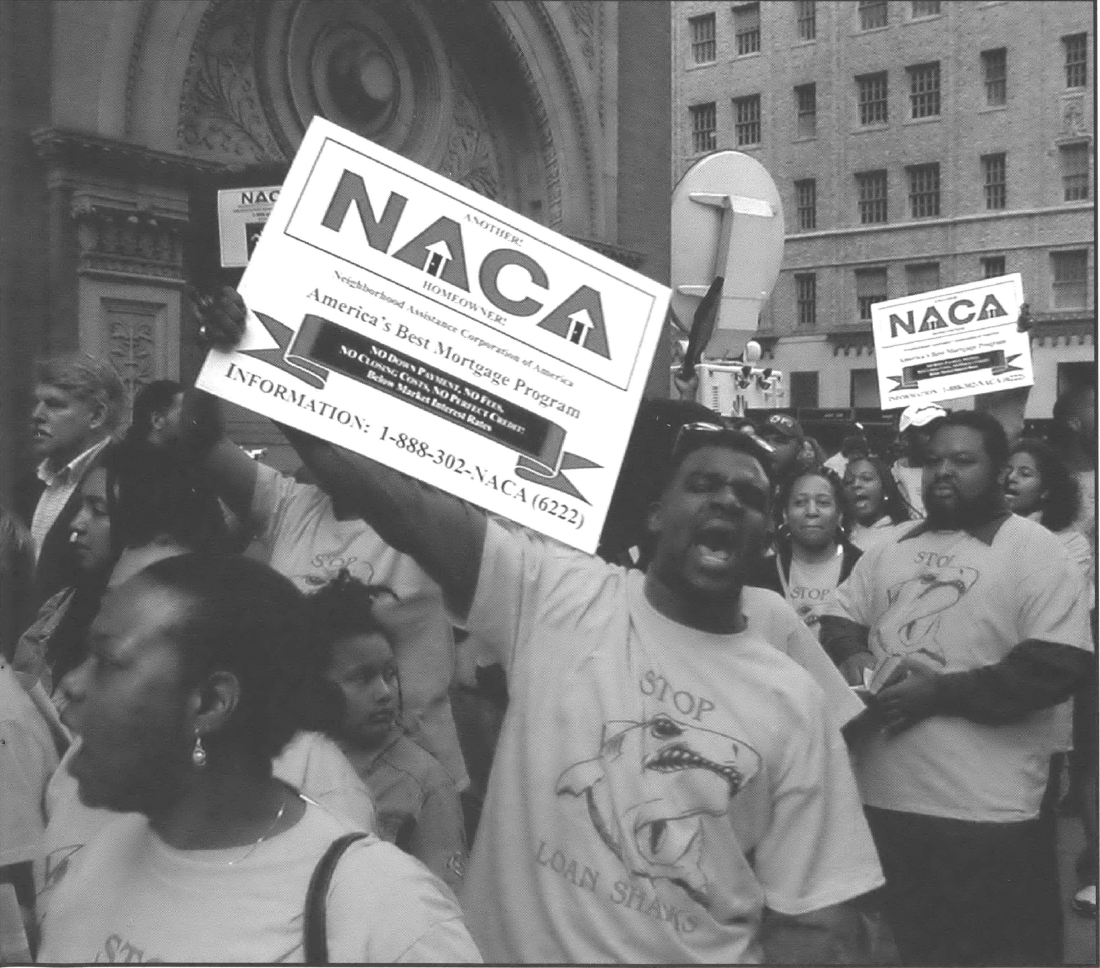

The Smiths and other borrowers never would have imagined dropping everything and traveling to New York. But they were given the opportunity by an advocacy group, the Neighborhood Assistance Corporation of America (NACA), which has spent more than 15 years making a name for itself by fighting lenders that prey on low-income, blue-collar, and minority homeowners.

This spring NACA spent $250,000 on the first phase of its campaign against Citigroup, sending out 142,000 surveys to CitiFinancial customers, fielding thousands of calls from disgruntled borrowers, and coordinating the transportation, lodging, and meals for 300 people to attend the stockholders’ meeting.

At 9 a.m. on April 15, the NACA borrowers and activists packed Carnegie Hall for the event, having gained the right of entry thanks to the 300 shares of Citigroup stock that NACA had purchased in anticipation of this moment. It was an impressive accomplishment, so impressive that even before the meeting Citigroup agreed to consider amending or rewriting the loans of all the borrowers who’d contacted NACA about their problems.

NACA chief executive Bruce Marks says the key to kicking open the door at Citigroup’s highest levels was a combination of research, grass roots organizing, and tactical planning. “They don’t fear individuals acting out,” Marks says. “They fear people who are organized and speaking with one voice. That’s what scares the hell out of them.”

Marks’s organization is one of a growing number of groups—including ACORN, Fair Finance Watch, and others—that are now fighting battles against abusive “subprime” lenders.

Marks says the key to organizing the victims of predatory lending is convincing them they’re not alone. “People think it just happened to them, and blame themselves,” he says. When they discover they’ve been systematically targeted and ripped off, they’re eager to link arms and fight back.

That sort of grassroots work has made NACA the scourge of bankers since the early 1990s. Marks and his Boston-headquartered group first gained national prominence by taking on Fleet Finance, an Atlanta-based company accused of defrauding low-income and elderly African-Americans.

As part of a series of settlements, the company’s parent, Fleet Financial Group, agreed to funnel loan money through NACA, allowing the group to offer low-interest mortgages to consumers who otherwise might be stuck with high-cost subprime ones. The victory over Fleet gave Marks the clout to force still more loan commitments from First Union, Bank of America, and other big institutions.

In all, NACA claims $4.3 billion in commitments that have allowed it to open 30 advocacy/loan offices around the nation, half of which are in the South, with more opening soon.

How well NACA will fare in its campaign against Citigroup is unclear at this point. In recent years, the company has rewritten some borrowers’ loans at the behest of activist groups, but it is yet to end unfair and exploitative practices in its subprime lending empire.

Can NACA accomplish what others haven’t, not just resolving the problems of a few thousand wronged borrowers, but forcing relief for millions of customers who’ve been mistreated and ensuring lasting reforms that prevent more Citi borrowers from getting gouged in the future?

Peter Skillern of the Community Reinvestment Association of North Carolina worries that deals between Citi and activist groups can “stymie systematic reform” by providing the company with public relations cover without truly forcing it to change its practices.

Marks says Citigroup has made “a positive first step” and that his group’s record as the nation’s most relentless opponent of predatory lending makes it clear that NACA won’t give up until the job is done.

Given NACAs earlier promises to “take over” Citigroup’s stockholders meeting, the event itself was something of an anti-climax. Because it was in the midst of negotiations, and because it was hoping to get satisfaction for the borrowers who’ve come to it for help, NACA offered a subdued presentation rather than fiery protests. Marks listed concerns about CitiFinancial’s practices, brought forward four borrowers to describe typical complaints, and thanked Citigroup for its promise of cooperation.

NACA didn’t press Citigroup CEO Sanford Weill to answer questions about CitiFinancial’s conduct. That was left to another advocacy group, Responsible Wealth, which has been pushing a stockholders resolution that would tie executive compensation to progress in ending predatory lending. In the face of Responsible Wealth’s challenge, Weill flatly denied that Citi engages in predatory lending.

Borrowers who attended the meeting said afterward that they were thankful to NACA for giving them a fighting chance in what, for them, had seemed a hopeless battle. Maria Flores, who rode 17 hours from Atlanta to be there, says she’s heartened to know “someone is willing to help” and do the hard work of bringing together people like herself. Still, she’s skeptical about how willing Citi is to make amends.

Like other borrowers who attended the stockholders gathering, Flores met afterward with a CitiFinancial counselor. She says he showed little interest in acknowledging the abuses involved in her loan, telling her it was “not that bad” and “it will pay for itself at the end.” “He asked me what I did want to happen with the loan,” Flores says. “He said, ‘Keep in mind that you did borrow the money.’ I said, ‘I never said I didn’t.’ To me that was kind of confrontational.” Marks says there was one counselor “we didn’t feel comfortable with. Those issues were addressed, and they were resolved.”

Whatever happens with her case, Flores believes it will take a long battle before the people at the top of Citigroup are willing to change their company’s ways. “They’re trying to pacify the activists,” she says. “I think they’ll take their sweet time responding, until they’re really forced to. They say CitiFinancial promised in 2000 to stop doing what they did to me. And here I was in 2002 with the same kind of loan.

Tags

Michael Hudson

Mike Hudson is co-author of Merchants of Misery: How Corporate America Profits from Poverty (Common Courage Press), and is a frequent contributor to Southern Exposure. (1998)

Mike Hudson, co-editor of the award-winning Southern Exposure special issue, “Poverty, Inc.,” is editor of a new book, Merchants of Misery: How Corporate America Profits from Poverty, published this spring by Common Courage Press (Box 702, Monroe, ME 04951; 800-497-3207). (1996)