This article first appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 31 No. 2, "Banking on Misery." Find more from that issue here.

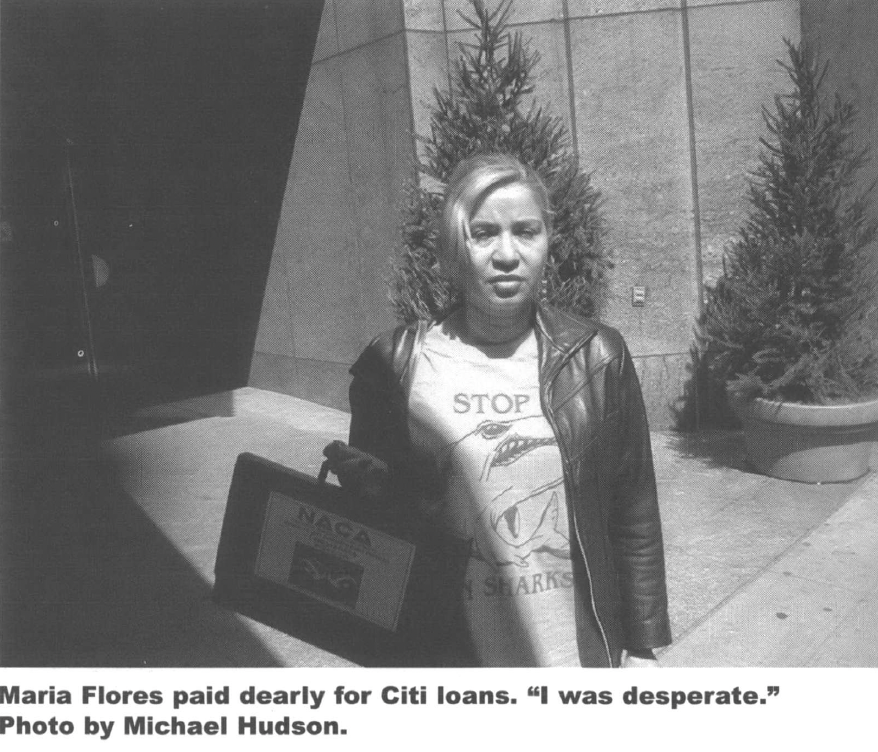

Maria Flores felt trapped. Breaking up with her boyfriend had stuck her with loan payments she couldn’t keep up. She says a manager from a CitiFinancial branch in Atlanta threatened to send someone to her job with an arrest warrant and tell her boss she was a deadbeat.

Flores says the manager told her she needed to come in and get a new loan. She thought she had no choice.

So she signed—taking out a second mortgage and digging herself into a deeper hole with CitiFinancial and, by extension, with the finance company’s corporate parent, Citigroup, the nation’s largest and most powerful bank company.

And her problems didn’t end. As she fell behind again, she says, CitiFinancial forced her to write post-dated checks to try and catch up. When that didn’t help, CitiFinancial had another solution: yet another loan.

Flores says branch employees led her to believe she had to buy credit insurance to get the new loan—and folded and flipped the papers so quickly and deftly as she signed that she didn’t realize the insurance would cost her nearly $700 the first year alone.

The July 2002 deal carried a 17.99 annual percentage rate, or about triple the market rate for home loans. Nearly all the $17,398 mortgage represented debt rolled over from her previous loan; it cost her $304 in fees to get $93.45 in new money.

She knew it was a lousy deal. But what choice did she have?

“I was desperate,” she says. “I thought they were going to take my house.”

So, like millions of other CitiFinancial customers, Maria Flores did what she thought she had to do. She signed the papers.

Subprime Time

Over the past year, Citigroup and its CEO, Sanford I. Weill, have been buffeted by investigations into the company’s misadventures with Enron, WorldCom, and other ill-fated Wall Street players.

But is there an overlooked scandal brewing for Citi in places far from Wall Street? In Southern hometowns such as Selma, Ala., Ashland, Ky., and Knoxville, Tenn., people complain Citigroup has taken advantage of them in an unglamorous part of its financial empire—personal loans and mortgages aimed at borrowers with bad credit, bills piling up or, in many instances, simply a trusting nature. Unhappy customers claim the company manipulated them into paying excessive rates and hidden fees, refinancing at unfavorable terms, signing deals that trapped them into bankruptcy and foreclosure.

These borrowers are part of the growing “subprime” market for financial services. They are mostly low-income, blue-collar and minority consumers snubbed by banks and credit card companies. Still others are middle-class consumers who have hit hard times because of layoffs or credit card-fueled overspending. Whatever their circumstances, they pay dearly. Citi’s subprime customers frequently pay double or triple the prices paid by borrowers with Citi credit cards and market-rate mortgages—annual percentage rates (APRs) generally between 19.0 and 40.0 on personal loans and 8.5 and 21.9 on mortgages. And beyond exorbitant APRs, critics and lawsuits claim, Citi has fleeced customers with slippery salesmanship and falsified paperwork.

A seven-month investigation by Southern Exposure has uncovered a pattern of predatory practices within Citi’s subprime units. Southern Exposure interviewed more than 150 people—borrowers, attorneys, activists, current and ex-employees—and reviewed thousands of pages of loan contracts, lawsuits, testimony, and company reports. The people and the documents provide strong evidence that Citi’s subprime operations are reaping billions in ill-gotten gains by targeting the consumers who can least afford it.

Who’s Targeted? Numbers Tell the Story

While not all subprime loans are predatory (subprime refers to loans to people with credit challenges), the overwhelming majority of predatory loans are subprime. Given this observation, it is instructive to see which communities are targeted for subprime lending:

African-American: Lower-income African Americans receive 2.4 times as many subprime loans as lower-income whites, while upper-income African Americans receive 3 times as many subprime loans as do whites with comparable incomes.

Hispanic: Nationally, borrowers living in areas where Hispanics were 75% of the population were twice as likely than borrowers living in white areas to receive a subprime loan.

Southern: In 17 metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs), the level of subprime lending is more than 1.5 times the national norm: 14 of these are in the Southeast or Southwest, and 7 are in Texas. El Paso has the highest proportion of subprime loans in the nation, at 47% of all loans.

Females: Almost 40% of single women borrowers got their refinance or home equity loans from high-cost subprime lenders, compared to one-third of men. In certain parts of Texas, women took subprime loans at a 2-to-l ratio over men.

Elderly: Borrowers 65 years of age or older were three times more likely to have a subprime loan than borrowers under 35.

Rural: One in four rural households is considered “cost-burdened” by housing payments, meaning that housing expenditures consume more than 30% of their monthly income. As a result, lenders consider many rural residents bad risks—a condition that contributes both to individual residents’ difficulty in obtaining credit and to a general lack of access to credit.

Sources: Center for Community Change, “Risk or Race? Racial Disparities and the Subprime Refinance Market,” May 2002; Federal Home Mortgage Disclosure Act; Consumers Union/Austin, “Texas Women and Elderly Pay More for Refinance and Equity Loans,” April 2003; AARP Public Policy Institute; Congressional Rural Caucus.

“It’s a pretty lowdown company that would take advantage of the working poor like this,” says Tom Methvin, an attorney with Beasley, Allen, an Alabama firm that represents hundreds of borrowers who claim Citi did them wrong. “Behind the curtains, they prey on the most vulnerable people in our society.”

Citi, critics say, is a model for America’s financial apartheid: a company that’s slow to offer affordable credit to minority and moderate-income communities (see “Reinventing Redlining,” p. 24), then profits by pushing a costly alternative. Citigroup argues that its prime lenders turn customers away because of legitimate assessments of credit histories, and that its subprime units must in turn charge more because their risks are greater.

These assertions are called into question by the fact that Citi’s subprime lenders charge high rates even to borrowers whose credit records would qualify them for competitive-rate loans. A national study by the Community Reinvestment Association of North Carolina (CRA-NC) concluded that large numbers of so-called “A-credit” customers are being charged higher rates only because they had the misfortune of walking into one of Citi’s subprime mortgage units rather than one of its prime-rate lenders.

The study estimated this group includes nearly 90,000 predominately African-American customers who took out first mortgages in 2000 from Citi’s panoply of subprime lenders. According to CRA-NC’s calculations, these borrowers paid an average of $327 a month more in interest than their prime-rate counterparts, or an overcharge of $110,000 per borrower by the time the loans are paid off. Over the lifetime of their loans, these borrowers’ excessive payments could total as much as $5.7 billion.

The company counters that it “has long maintained very high standards” within its subprime operations. It says it doesn’t discriminate or gouge customers. Spokesman Steve Silverman denied requests for an interview with Weill and said privacy concerns prevent the company from commenting on individual borrowers’ cases. Nevertheless, Silverman says Citi has worked to address complaints about the way the subprime industry does business: “We’ve really taken a leadership position on these issues and tried to raise the bar for the industry and, frankly, for the benefit of consumers.”

The company has reined in some of its worst abuses, but it has done so under pressure from activists and government. The changes fall short of eradicating unfair practices—and in many instances seem little more than empty gestures.

In his public statements, Weill has rejected the idea his company victimizes anyone. In January, he told investors Citi “has become a leader in lending to people who wouldn’t qualify to get loans from banks, or are embarrassed to go into a bank. We have to be very careful that we quantify predatory lending as really something that is predatory lending, and don’t take the market away from people that really need credit.”

Citigroup’s push into the subprime market is a dramatic example of how the merger of high and low finance is playing out on Wall Street and on side streets across the South. It’s also the story of how one man blazed a less-traveled path to Fortune 500 ascendance for himself and for others who would imitate his example. And, finally, it’s a case study in how large corporations can fight off scandal and avert lasting reform through a skilled combination of legal maneuvers, tactical retreats, PR stratagems, and power politics.

Citigroup has established itself as perhaps the most powerful player in the subprime market by swallowing competitors and employing its vast capital resources and name-brand respectability. CitiFinancial, its flagship subprime unit, claims 4.3 million customers and 1,600-plus branches in 48 states, including nearly 350 offices across the South.

Things don’t stop with CitiFinancial, however. The web of subprime is woven throughout Citigroup. Sandy Weill’s company has refashioned itself into a full-service subprime enterprise—one that makes high-cost loans, writes the insurance wrapped into the contracts, buys other lenders’ portfolios and sells securities backed by the income streams from all these transactions. Citibank is now banking on subprime. In 2000, one study calculated, nearly three of every four mortgages originated within Citigroup’s lending empire were made by one of its higher-interest subprime affiliates—nearly 180,000 loans out of a total of 240,000-plus mortgages for the year.

The downscale market is vital to Citi’s plans for prospering in a tough economy. Citigroup slid by with a three percent increase in core income in 2001. CitiFinancial, in contrast, posted a 39 percent hike. Last year the story was much the same. CitiFinancial’s income grew 21 percent, topping $1.3 billion, or nearly one-tenth of Citigroup’s take for the year. Add that to subprime-related receipts at its investment banking and insurance operations, and subprime’s contribution to the global parent’s bottom line becomes even clearer.

Subprime’s importance isn’t just a matter of balance sheets. It’s rooted in the company’s history and evolution. Citigroup looks the way it does today because Weill bought a middling-sized subprime finance company and used it as a vehicle to acquire other companies and create a behemoth that put him in position to win the biggest prize of all: Citi. The 1998 merger was, at the time, the largest in history, uniting Citicorp, Travelers Insurance, Primerica, Commercial Credit, and Salomon Smith Barney. Along the way, the media lionized Weill as the King of Capital, CEO of the Year, a daring dealmaker who lived by the philosophy, “How you get there isn’t as important as where you’re going.”

But tales of impropriety at Weill’s subprime companies—before and after the merger—raise uncomfortable questions. Was Sandy Weill’s climb to power at the world’s most powerful bank financed by shady loans targeting desperate and unwary consumers? Is today’s Citi a company built on a foundation of duplicity and exploitation?

The Platform

He was a kid from Brooklyn, the grandson of immigrants, a first-generation college man who began on Wall Street as a $35-a-week clerk. At age 27 Sandy Weill started his own brokerage and built it with a relentless campaign of acquisition. Eventually he won the number two spot at American Express. But he was driven and pugnacious, and left frustrated with the company’s old-boy system. In 1986 he found another challenge, buying Commercial Credit, a loan company based in Baltimore. The rise in personal bankruptcies frightened some investors, but Weill smelled opportunity in this humble business of small loans to average folks.

He assembled his management team and headed for Baltimore. As Monica Langley recounts in her Weill biography, Tearing Down the Walls, buying Commercial Credit was the first step in his climb back to the top. “Think of it as a platform,” Weill told his deputies. “We need a financial services company to grow from.”

Langley writes that the new administration’s enthusiasm was interrupted by Weill’s assistant, Alison Falls, who understood Commercial was built on lending at high rates to borrowers with nowhere to turn. The company’s legal dustups had included a 1973 Federal Trade Commission order that it stop using underhanded means to sell credit insurance. “Hey guys, this is the loan-sharking business,” Falls said. ‘“Consumer finance’ is just a nice way to describe it.”

Weill entertained no such qualms. He likened Commercial Credit to Wal-Mart, implying it was snobbery to suggest blue-collar folks in small towns shouldn’t have access to credit. “This is Main Street, America,” he said.

Indeed, high-cost finance companies were nothing new, especially in the South. But deregulation and Wall Street know-how were transforming a balkanized industry into an enticing market for some of corporate America’s biggest names, including ITT and Fleet.

Salomon Brothers pioneered the mortgage-backed securities market: loans made by local operators were bought by bigger institutions, which in turn used Salomon to create investment products sustained by revenues from these high-yield mortgages. The profits bankrolled an army of quick-buck lenders. Many customers were ensnared through “loan flipping”: repeated refinancings that rolled in new fees and insurance, making their debt grow ever larger. Lawsuits and congressional hearings ensued, forcing some predators—Fleet and ITT among them—out of the business.

By the time Weill arrived, Commercial Credit, too, was on the verge of going out of business—not because of legal problems, but because of nose-diving profits and excessive corporate debt. Weill turned things around, introducing an entrepreneurial style that gave branch managers stock options and bonuses for meeting goals. “He has a 100 percent hands-on focus,” Charles Prince, a Weill advisor since his Commercial Credit days, once recalled. “And no detail is too big or too small.” In six years profits rose from $25 million to $193 million. The company grew in leaps. In 1990, Commercial gained $1 billion in receivables by buying the consumer finance arm of Barclays Bank.

Closed Folders

Frank Smith worked for Barclays in Mississippi when his branch joined Weill’s burgeoning network. Commercial seemed a good company to work for at first. But things changed. It became a numbers game: management prodded Smith and other branch managers with quotas for generating loans and selling insurance. “Over a period of time,” Smith says, “it went from a family, employee-oriented company—doing the right thing, trying to help its customers—to this cutthroat thing of anything that will get us more business.”

Sherry Roller vanden Aardweg, who worked for Commercial in Louisiana from 1988 to 1995, agrees there was “a tremendous amount of pressure” to sell insurance: “We kept adding insurance that we could offer. It just kept growing. It was beginning to get a little bit ridiculous.”

Credit insurance covers a loan if a borrower dies, gets sick or injured, or becomes unemployed. Consumer advocates call it an overpriced rip-off, and charge that subprime lenders break the law by stealthily slipping it into loan contracts or by telling customers they can’t have the loan without it. It was a big moneymaker for Commercial because it was often sold through a Commercial-owned insurance company, American Health & Life, which wrote some of the costliest products in the business (see “Citi and Credit Insurance”).

Smith believed credit insurance benefited borrowers, but he worried about how aggressively it was sold. He says auditors from American Health & Life would pointedly ask: “Why didn’t you sell this person the insurance?” Selling it became a game of semantics and psychology. Loan officers never said “insurance.” They spoke of “payment protection.”

When customers applied over the phone, employees focused on what monthly payment they could afford. When these customers came to the office, Smith says, many loan officers conducted “closed-folder closings.” The documents would be prepared with insurance already included. The loan officer emphasized the monthly payment, dancing around the question of insurance and interest.

“It’s the idea that ‘This is the monthly note we talked about. We don’t have to get into a lot of detail,’” Smith explains. “The whole time you have the check on top of the folder. They need the money or by God they wouldn’t be at the finance company. They’d be at a bank.” Once the documents came out, most customers signed quickly and unquestioningly.

Smith says he complained about this practice, but management brushed him off. He left in 1999 on less-than-happy terms; he says the company accused him of misconduct in his handling of an excessive phone bill. He’s now a sergeant with the Pike County (Miss.) Sheriffs Office.

“I’ve tried to forget everything about Commercial Credit,” he says. “I sleep good at night.”

By the time Smith departed, Commercial was battling lawsuits around the South. In 1999, the company agreed to pay as much as $2 million to settle a lawsuit accusing Commercial and American Health & Life of overcharging tens of thousands of Alabamans on insurance. The companies admitted no wrongdoing, saying state regulators had OK’d the way they calculated insurance charges.

More cases are still winding through the courts. In January, Jackson, Miss., attorney Chris Coffer says, he obtained confidential settlements for about 800 clients with claims against Commercial Credit or its successor, CitiFinancial. Tom Methvin’s firm, Beasley, Allen, claims nearly 1,500 clients in Alabama, Mississippi, and Tennessee who had Commercial Credit or CitiFinancial loans. In Mississippi’s Noxubee and Lowndes counties, these clients include Pearlie Mae Sharp, Johnny Slaughter, Mattie Henley and Martha and Arthur Hairston, five African Americans who borrowed money from Commercial in the mid-1990s. Sharp paid $1,439 to insure a $4,500 loan. Slaughter paid an APR of 40.92 and bought disability insurance even though he already had a disabling spinal injury. Henley paid an APR of 44.14.

“Once they say ‘You get the money’—to me, they really didn’t explain everything,” Martha Hairston says. “They just said ‘Sign this, sign this.’” The Hairstons paid $1,164 for five kinds of insurance on a $5,001 loan. Arthur Hairston, a church maintenance worker, says he and his wife “hit bad times a time or two,” and their Commercial Credit loans made things worse. When you fall behind, he says, “they almost force you into refinancing. When you do that, boy, they give you a triple whammy then.”

In March, a federal judge threw out Sharp, Slaughter, and Henley’s cases, ruling they had waited too long to file their suits. Roman Shaul, an attorney for Beasley, Allen, says the firm will appeal. He says the borrowers’ low reading levels prevented them from understanding disclosures informing them of the state’s statute of limitations.

The finance industry argues that customers have a responsibility to read and understand loan documents. Borrowers, the industry says, shouldn’t be able to sign contracts and then try to back out later.

When Sharp, who has a sixth grade education, testified she couldn’t see well enough to read her documents, the company’s attorney asked if she’d told the loan officer: “Did you tell him that you couldn’t understand basic sentences in the English language well enough to make decisions about it?” She acknowledged she hadn’t, but said the loan officer should have explained things better.

“He should have did right,” she said.

Walking, Talking Bank

As money poured in, Commercial’s CEO hunted bigger prey. In 1988 Weill spent $1.7 billion to acquire Primerica, an insurance and finance giant. He consummated a takeover of Travelers in 1993 and, in 1997, grabbed Salomon Brothers and Security Pacific Financial Services. All that was mere prelude to the 1998 Citigroup takeover, which capped a 12- year rise that made Weill a billionaire and created the largest financial company in history.

Weill enthused about blending diverse units and creating opportunities for “cross selling,” which allows affiliates to market each other’s products. Primerica boasts more than 100,000 agents who can not only sell life insurance but also steer loan applicants to the parent’s subprime operations. In Weill’s vision, he’d created “a walking, talking bank.”

Amid the excitement of the deal, the pundits failed to note the history of dubious activities at Commercial Credit and other segments of the organization that had captured Citi. Before it was absorbed into Commercial, Security Pacific Financial Services had taken heat for buying mortgages from some of America’s worst loan sharks. Salomon was humbled by scandal in 1991, when it paid $290 million to settle charges it used phony bids to manipulate the U.S. Treasury bonds market. More recently, activists staged protests against Salomon Smith Barney for marketing securities backed by $3 billion in mortgages from Ameriquest, a subprime lender whose corporate predecessor, Long Beach Mortgage, had been forced to surrender $4 million to end a U.S. Justice Department lawsuit accusing it of gouging elderly and minority women.

Primerica’s history of strife includes a $500,000 fine from New York authorities, who charged the company with deceptive salesmanship, and a censure from Tennessee regulators for seeking to “deceive and confuse” consumers through “a system of deliberate evasion” of the law. A spokesman said Citi has imposed “a strong compliance culture” that has made Primerica an industry model. But lawsuits in Mississippi have alleged continuing misconduct, accusing Primerica of using unlicensed agents who pose as “personal finance analysts” and use fast talk to entice people to buy insurance and refinance into higher-rate mortgages.

As for Commercial Credit, it took a new name—CitiFinancial—but seemed to do little to change its ways. In Knoxville, Tenn., CitiFinancial charged Loretta and Danny Jones $7,242 in insurance premiums on a $34,075 loan. When they signed the mortgage in June 2001, Loretta Jones says, their loan officer knew her husband had a history of heart problems that would disqualify him from getting life insurance—or disqualify his widow from collecting if the worst happened. When they were going over the insurance papers, she says, the loan officer told them to leave the section about her husband’s pre-existing conditions blank. But when they got a copy of the branch’s documents later, she says, they found someone had checked “No” on the question about heart problems.

After her experiences with CitiFinancial, she says, she trusts no one. “Because everybody will screw you one way or another. They’re just out for their own almighty dollar.”

Citi and Credit Insurance: Profits and Price

Credit insurance is a big money-maker for Citigroup because its subprime lenders peddle insurance written by sister companies, a form of cross-selling that allows the corporate parent to reap the benefits from both commissions and premiums on the insurance.

Consumer advocates say credit life insurance is the nation’s worst insurance rip-off—and statistics collected by the National Association of Insurance Commissioners show that Citigroup subsidiary American Health & Life Insurance sells some of the costliest policies in America.

NAIC says the best way to evaluate insurance pricing is to calculate how much an insurer pays in claims for every premium dollar it collects. Most types of insurance pay 65 to 85 cents in claims for every premium dollar, and NAIC recommends credit life insurance be priced so the loss ratio is at least 60 cents on the dollar.

From 1998 to 2000 (the most recent years for which figures are available) American Health & Life paid barely half that amount—just 33.7 cents in claims for every credit life premium dollar. That’s a woeful figure even by the less-than-stellar standards of the credit life insurance industry, which as a whole paid 41.2 cents on the dollar during that period.

Citi spokeswoman Maria Mendler says its credit insurance is a good value for customers worried about how their families will pay the loan if catastrophe strikes: “Oftentimes there are real-life reasons why people can have credit issues—they become ill, they get a divorce, they lose a job—and often we can help them back to good credit by providing them with loans and then working with them so they can pay them off and get back on track.”

Jean Ann Fox, consumer-protection director for the Consumer Federation of America, says that argument doesn’t add up. “Any company that’s writing insurance that pays out 30 cents on the dollar, obviously that insurance is being sold to benefit the creditor, not the borrower,” she says. “This is just about increasing the cost of the credit. . . . If you want to buy life insurance, you should buy life insurance that protects your spouse, not your banker.”

The Big Score

Sandy Weill’s subprime operations were raking in dollars, and they weren’t alone. By the late 1990s, Texas-headquartered Associates First Capital Corp. had built itself into the nation’s subprime leader, having posted record profits 25 years in a row. In 1999, earnings approached $1.5 billion.

For Weill, Associates was a tantalizing target. In late 2000, market watchers cheered as Citi announced it was buying Associates in a $31 billion deal. “I really think Sandy scored,” one money manager told the New York Times. “It may not be his biggest deal, but it may be his best deal. It’s a superb strategic and tactical fit.”

Fair-lending groups had a different view. They knew Associates had been built on a well-documented record of corruption. In 1997, an ex-employee from Alabama told ABC’s Prime Time Live that his Associates branch had a “designated forger” responsible for doctoring loan papers. Associates’ unabashed style spawned lawsuits and investigations, forcing $33.5 million in settlements in North Carolina and Georgia. All the while, Associates expanded its reach by serving as a clearinghouse for the remnants of other predatory lenders, buying up Fleet’s loan portfolio and hiring hundreds of former ITT employees.

Why would Citi wed itself to the nation’s worst subprime plunderer? “No company that values its good name would have bought Associates,” said Martin Eakes of North Carolina’s Self-Help Credit Union, challenging Weill at a stockholders’ meeting in April 2001. Weill responded that Citigroup was cleaning up Associates by merging it into CitiFinancial.

The transition hit a snag that spring, however, when the FTC sued Associates over its credit insurance practices. Citigroup fought back, seeking to dismiss the case by arguing Associates no longer existed. The FTC countered with affidavits from two former managers who said CitiFinancial was just as bad as Associates. Gail Kubiniec said CitiFinancial packed loans with insurance if a customer “appeared uneducated, inarticulate, was a minority, or was particularly young or old. The more gullible the consumer appeared, the more coverages I would try to include in the loan.” Michele Handzel said CitiFinancial created so much pressure to “flip” customers into new loans “that some employees did not even bother to obtain customers’ signatures” on the refinancings.

The company called the allegations “an affront to the thousands of CitiFinancial employees who every day work in the best interests of their clients.”

With attention expanding beyond Associates, Citi moved to prevent the investigation from spinning out of control. It cut a deal. This past September the FTC announced Citigroup had assented to settlements totaling $240 million. As many as two million customers might benefit.

Media coverage accentuated what the FTC and Citigroup wanted in the headlines: the deal was the largest consumer protection settlement in FTC history—and an effort by Citigroup to straighten out an old mess. “These problems basically related to a company before we acquired it,” Weill explained.

But behind the spin, questions remain. Matt Lee, director of the Bronx-based Fair Finance Watch, contends the FTC “let Citigroup off absurdly cheap.” Simple math shows the average payout will be just $120 per victim; even the $240 million grand total represents less than two weeks’ profits for Citigroup. And because the deal covers only Associates, it does nothing to hold CitiFinancial responsible for its own transgressions.

No Mystery

The FTC settlement was part of Citi’s long-term strategy for repelling attacks on its subprime operations. It has quietly settled some lawsuits, fought off others by forcing customers to take their complaints into arbitration (see “Access denied”), and, most notably, announced a series of reforms designed to forestall stronger regulatory initiatives.

Many reforms were unveiled after objections to the Associates purchase emerged. Others came just before the FTC settlement.

Some appear authentic, including the directive that employees quote monthly payments without insurance included. Southern Exposure checked 20 CitiFinancial offices around the country and found almost all took pains, over the phone at least, to emphasize insurance was optional. However, some still used the euphemism “payment protection,” rather than simply saying “insurance.”

On the whole, the company’s reforms seem more about image polishing than genuine remedies. For example, Citi promised to dispatch undercover staffers to make sure employees follow the rules. Then it gave a heads-up about when the testers were coming. In November 2000, the head of CitiFinancial’s Southeast division instructed regional managers to inform district managers and branch staffers that “we will begin a Mystery Shopping Test in December and complete in January. A minority and a Caucasian [sic] will visit the same or separate branches and request an identical loan.”

Citigroup said the memo did not undermine the testing, because the company had already announced the effort. “That we conduct mystery shopping is no mystery,” a spokesperson said. But critics say divulging time windows defeats the purpose of testing how customers get treated under normal circumstances.

As part of its initiatives, Citi also promised to terminate relationships with many mortgage brokers affiliated with Associates, offer lower-cost refinancings to customers who have good credit but are paying subprime rates, and likewise have subprime units redirect “A-credit” applicants to Citi’s prime lenders.

But a reading of Citi’s own reports shows these changes are more about symbolism than substance:

■ CitiFinancial suspended more than 5,500 brokers; only about 2 percent of them were excluded due to “integrity concerns.” Most were terminated because of “inactivity” or failure to return paperwork.

■ CitiFinancial identified more than 25,000 subprime customers who qualified for prime-rate mortgages; by the end of 2002, only 110 had “graduated” into lower-rate loans.

■ Citi’s subprime units referred 12,141 new applicants to prime-rate affiliates in 2002; by year’s end, just 278 had found prime loans through the “Referral Up” program.

The reform process has been called into question, too, by continuing allegations the company is using harsh collection and foreclosure tactics to keep squeezing money out of fraud-tainted Associates accounts (see “Reforming Foreclosures” and “Collecting Trouble”). And it’s been called into question by the experiences of borrowers who took out loans long after Citi’s reforms were supposed to be in place.

Household Name: Citi’s Chief Rival Has a Rocky History, Too

Citigroup isn’t the only big lender that’s been accused of mistreating disadvantaged consumers. Just like Citi, Household International has left a trail of unhappy borrowers.

In Miami’s Dade County, 89-year-old Madie Bell Wilson was evicted from her home after taking out a loan from Household that she thought was a home-repair grant she didn’t need to pay back.

In San Antonio, 63-year-old Mary Salas said a Household subsidiary, Beneficial, quoted her an interest rate of less than 11 percent on a mortgage on her home. Later, she discovered the real rate was almost 26 percent.

Those sorts of cases drew’ the scrutiny of law enforcers. In October, Household agreed to pay up to $484 million to settle predatory-lending allegations pushed by a coalition of state regulators and attorneys general.

“We apologize to our valued customers for not always living up to their expectations,” CEO William Aldinger said.

Florida Attorney General Bob Butterworth said the settlement was part of an effort “to change the way this industry does business.” But housing activist group ACORN said the settlement was small compared to the $8 billion it estimates Household has plundered from customers in recent years.

Despite the history’ of abuse, federal regulators gave blessing this spring to London-based banking giant HSBC in its bid to purchase Household. Aldinger will be CEO of HSBC’s enlarged U.S. operations.

In Chicago, the National Training and Information Center studied a sample of mortgages made in the first half of 2001 and concluded that “CitiFinancial continues to engage in predatory lending practices despite the company’s promises of reform.” Of the borrowers surveyed, 56 percent said Citi engaged in insurance packing, “bait and switch,” or other trickery.

In Tuskegee, Ala., Belinda Patrick says she came away feeling targeted because of her race after she and her husband signed loans with CitiFinancial in November 2001 and February 2002. The first one, a $5,515 personal loan, carried a 28.96 APR and was topped by $2,024 in insurance premiums. The next one was a mortgage with a 21.99 APR and still more insurance. She says the money was much needed, but the rates were exorbitant and insurance was included without the couple’s approval.

In Woodstock, Ga., Donna Durick says CitiFinancial ran a bait and switch on her July 2002 mortgage. She says she was told her 9.39 APR would be fixed for two years. It turned out, she says, that her mortgage rate could increase 1.5 points every six months, and could go as high as 28.89. Durick says she has been trying for months without success to get signed copies of her loan documents.

In Atlanta, Gaylon Barnes says a loan officer talked him into buying three kinds of insurance—life, disability, and unemployment—when he took out a second mortgage in November 2002.

“I didn’t want this at first. He explained to me it was a great deal. So I said ‘OK, I’ll get it.’” CitiFinancial didn’t explain, Barnes says, that the insurance would spike his monthly payments from $213 to $280, costing him more than $800 extra in just the first year.

The cost of the $15,262 mortgage was pushed even higher by a $457 origination fee and a 14.99 APR. Barnes, a heating and air conditioning repairman, says that if Citi is changing its ways, “I can’t tell.”

Barnes’s story is evidence that selling insurance is still a big part of CitiFinancial’s business model—a reality borne out by the fact that the company still uses insurance-sales goals to help determine managers’ and loan officers’ compensation.

CitiFinancial has told regulators that insurance sales are not “an overriding factor” in employee compensation, and that it has safeguards to ensure its bonus system doesn’t encourage workers to oversell insurance.

But Fair Finance Watch’s Lee says the bonus system is at the heart of how management controls employees’ actions—and how it cultivates predatory practices with top-down, scientific precision. “The moment people’s compensation is based on how much they sell, they’re going to be hard-selling it,” he says. “Citigroup knows that’s exactly how it works.”

Penny Fielder and Kelly Raleigh, two former CitiFinancial employees from Tennessee, agree. Fielder says management was still “pushing to max out all the loans” well into 2002, prodding employees to make sure customers had “full insurance” and were as deeply in debt as possible. Raleigh, a branch manager in Jefferson City until last summer, says the pressure to meet goals for insurance and refinancings makes abuses inevitable, regardless of what the company’s reform pronouncements say.

The message, Raleigh says, was clear: “Don’t get in trouble,” but “if you don’t hit your quota, you’re not gonna have a job.”

Spirit and Letter: Ex-Employee Said Citi Takeover Increased Rather Than Solved Problems

Steve Toomey was working as a loan officer in Charleston, S.C., for Associates First Capital Corp. in November 2000 when Citigroup purchased the embattled subprime lender.

Toomey stayed on under the CitiFinancial banner until May 2001. Soon after, he went public with allegations that Citigroup’s subprime lending practices violated “the spirit and letter” of the law and contradicted the company’s public pledges to end predatory lending at Associates.

According to an affidavit Toomey submitted to federal banking authorities, CitiFinancial began compensating loan officers for refinancing customers’ loans, including cases in which the borrowers’ rates were raised. Employees were instructed “to only disclose their prospective monthly payments, and not the level of points and fees that were being stacked into the loan.” He also alleged instances in which management “required employees to falsify information in borrowers’ files.”

After Citi took control, Toomey said, the Charleston branch’s management began secretly taping employees’ conversations. When he protested, he said, a company official told him CitiFinancial wouldn’t initiate an investigation “on a mere complaint by an employee.”

After news of Toomey’s allegations broke in July 2001, a Citigroup spokesman said Toomey had worked for CitiFinancial a short time and had raised questions only after “he concluded that the company would not pay him monies that he demanded to resolve an employment dispute.”

Citigroup said that “among the many allegations he described, we were able to corroborate only two isolated incidents and have taken appropriate corrective action.” The company would not say what infractions had been confirmed.

A Lousy Period

As CitiFinancial has crafted a public persona of reform- mindedness, it has also worked in other, behind-the-scenes ways to protect its image and reduce its legal vulnerability. Critics say these damage control efforts include aggressive attempts to muzzle whistleblowers.

In July 2001 Reuters news service reported Citigroup had hired a famed litigator “to help fight allegations of illegal lending practices and prevent former employees from bad-mouthing the financial services giant.” Reuters said Mitchell Ettinger, who defended Bill Clinton in the Paula Jones case, met with at least 15 current or former employees to remind them to keep quiet. A Citi spokeswoman explained that the “standard non-disparagement clause” in the company’s severance agreements wouldn’t apply to reporting illegalities.

Raleigh says CitiFinancial threatened her with jail and fired her after falsely accusing her of leaking information to critics. She says her problems began when she complained to management about disreputable practices, such as falsifying documents to qualify customers for insurance and collecting property insurance premiums to cover bogus items, such as cars that didn’t run. “They didn’t like me telling on anything that was being done wrong,” she says.

Fielder says she and two other employees were forced out last fall at CitiFinancial’s Morristown branch because the company suspected them, too, of leaking documents. According to Tennessee’s labor department, Citi suspended Fielder without pay and froze her 40IK. CitiFinancial also tried to block her unemployment benefits, arguing she had been suspended for misconduct. The agency concluded Citi had “offered no proof’ of its allegations.

Fielder spent 11 years with the company. She was there through the growth of the Commercial Credit era, the mega-deal that created today’s Citigroup, the warfare over Associates. “It just seemed like every year there would be more pressure to beat the numbers,” she says. “They’re so big now, and I think the little people are taken advantage of. . . . It just seems like the bigger they got, the harder it got.”

Citigroup is certainly big. It boasts $1 trillion in assets. Since 1986, Sandy Weill has spent $147 billion to acquire more than 100 companies. As he’s built this empire, he’s depended on the aides who helped him resurrect Commercial Credit. Prince, his longtime advisor, has taken charge at Citi’s investment banking operations. Robert Willumstad, another Commercial veteran, is Citigroup’s president. Both have been mentioned as a possible heir apparent.

These are tough times, however, for the CEO and his team. Weill became ensnared in allegations that he ordered a Salomon analyst to improperly upgrade AT&T stock. Citigroup will pay $400 million in a recently announced settlement with the Securities and Exchange Commission related to brokerage scandals, and Weill himself has been barred from talking to his own stock analysts without company lawyers present. “This has been a pretty lousy period to go through,” he said last fall.

Upfront Costs: “Single-Premium” Insurance Disavowal Only Goes So Far

Citigroup has made much of its decision to stop fattening real-estate loans with “single-premium” credit insurance, an exceptionally costly product because it rolls the high price of the insurance onto the front end of the loan, thus allowing the company to collect interest on the tacked-on premiums. Citi notes it was the first in the industry to drop the controversial product. But it doesn’t dwell on the fact that it still sells other kinds of costly insurance on mortgages—and that it has yet to disavow the sale of “single-premium” insurance on non-real estate loans.

Take, for example, the case of a Morristown, Tenn., customer who got a personal loan from CitiFinancial in May 2002. According to documents on file with banking regulators, her $5,000 loan was topped by $1,166 in “single-premium” life, disability and property insurance. With a $333 “service charge” and a $150 “maintenance fee” thrown in, her total principal surpassed $6,500—all financed at an annual percentage rate of 24.99.

A Citigroup spokeswoman explains that “the critics of single-premium credit insurance on real estate-secured loans claimed that when tied to a mortgage, this product could lead to the loss of a home. That is not an issue with credit insurance on a personal loan. Additionally, these products have been approved by state regulators and voluntarily purchased by borrowers for decades and have provided important benefits to many customers who would not otherwise be able to obtain insurance.”

Matthew Lee of Fair Finance Watch says selling single-premium insurance is predatory whether it’s on a personal loan or mortgage; if it’s wrong for one, he says, it’s wrong for the other.

For Lee, a long-time Citi critic, it’s no surprise these “ex-subprimers” who learned to operate “at the very edge or over the limits of the law” would engage in sharp practices once they gained control of a global conglomerate. At the same time, he believes the less-publicized problems inside Citi’s subprime operations won’t be solved so long as Citi is run by the same people who used subprime as their path to power.

“The guys at the top are not going to reform CitiFinancial,” Lee says. “Because they designed everything that is there.”

The Meeting

On a Tuesday morning in April, Sandy Weill stood alone on stage at New York’s Carnegie Hall. The occasion was Citigroup’s annual ritual, its stockholders meeting.

The gold-gilded hall was filled with a sea of yellow t-shirts emblazoned “Stop Loan Sharks.” An activist group, the Neighborhood Assistance Corporation of America, had brought 300 borrowers and supporters from around the country as a show of force in its campaign against Citigroup (see “Journey for Justice”).

The day before, in an effort to head off protests, Citi had promised to consider reworking the loans of borrowers who’d contacted the advocacy group for help. As part of the arrangement, four borrowers stood at the meeting and gave Weill brief accounts of their experiences. They had come too far to remain silent.

Among them was a family of six that had driven 22 hours from Tampa, Fla.: Doreen and Alan Fawkes and their four children, including the youngest, 22-day-old Joshua.

The family’s problems began with a high-interest loan from Associates. By the spring of 2001, the Fawkeses recall, they were struggling to keep up, and the new owner of their account—CitiFinancial—promised to refinance them and ease their burden.

Instead, the family says, the deal raised their monthly payments and spiraled their total debt upward. Keeping up became even more of a struggle. “If we were two days late, they would start calling at 8 o’clock, 8:30 in the morning,” Doreen Fawkes says. “The manager was very nasty.”

The worst blow came this spring. After Joshua was born on March 24, they arrived home from the hospital to discover CitiFinancial was putting their home up for sale in less than a week.

Only by scrambling to file bankruptcy did they put a brake—they hope—on the foreclosure.

“I’ve had awful nightmares about CitiFinancial,” Doreen Fawkes says. “We’ve lived in fear. If we did not have Jesus in the middle of our marriage, this would have torn a good family apart.”

At the stockholders’ meeting, she thumbed through Citigroup’s report on its subprime reforms. She didn’t buy Citi’s documentation of its good citizenship. “It just reminded me of a roll of toilet paper,” she says.

Early in the meeting, the chief executive had noted Citi’s securities scandals, acknowledging his company had engaged in some practices “which in hindsight did not reflect the way we want to do business.”

His semi-confessional tone changed, however, when the subject turned to the question of predatory lending. Weill offered no apologies to the Fawkes family. He offered no apologies to others who say their experiences belie CitiFinancial’s promises of reform.

“I think that CitiFinancial has been a leader in making changes” for the better in the subprime industry, the CEO told the Carnegie Hall crowd. He said CitiFinancial serves “millions and millions” of people who couldn’t get credit otherwise. “It helps raise up their quality of life and opportunity.”

Sanford Weill’s unwavering denial of misdeeds at CitiFinancial—and, before it, at Commercial Credit—is an indication of how important subprime is to his company’s past and to its future.

And it raises one more uncomfortable question: If Citigroup won’t admit it’s done wrong, how can it reform itself? Millions and millions of borrowers, ripped off and exploited by America’s largest financial institution and its corporate forebears, are still waiting for an answer.

Citi’s Reforms: Real or Imagined?

Citigroup says it “has raised the bar in the consumer finance industry by making significant changes in its lending practices” since it absorbed Associates First Capital Corp. into its subprime operations two and a half years ago. By putting strict standards on its brokers, reducing loan-closing costs, and instituting an array of other reforms, Citi says, it has made things better for its borrowers and even for the customers of other subprime lenders that have followed the company’s lead.

But many anti-predatory lending activists have their doubts about Citi’s reforms. John Taylor, president of the National Community Reinvestment Coalition, says some of NCRC’s member organizations have told him the changes are more public relations than genuine remedies: “There’s one set of facts that says: ‘This is our policy.’ There’s another set of facts that says: ‘This is what we’re really doing.’”

Martin Eakes of North Carolina’s Self-Help Credit Union agrees: “I really think that the reforms that Citi announced are cosmetic. There was absolutely no substance. It’s infuriating for me to watch the media and policymakers and regulators fall for this.”

Some activists are more hopeful. Peter Skillern of the Community Reinvestment Association of North Carolina believes Citi has worked to halt its many of the most outrageous abuses that Associates was known for.

But Skillern says Citi still exhibits “more discrete but nonetheless unfair lending practices,” such as charging subprime rates to customers who actually qualify for “A-credit” prices, a practice that disproportionately affects black borrowers.

“I will give them recognition that they have moved farther along than the blatant theft that Associates practiced,” he says. “But they’re still costing people billions of dollars. Because of their size, any one of their unethical practices has an impact on the whole country.”

Citi Responds

For this story, Citigroup declined to answer questions about specific customer or ex-employee complaints. CitiFinancial spokesman Steve Silverman says the company would not respond “to each individual scenario. We just don’t do that.” He said that “when customers have questions and complaints, we have a toll-free number and want customers to use it And we try to be responsive.” The same holds true, he says, for employees, who can use an ethics hotline to voice their concerns.

Many questions about the company’s policies were answered with the suggestion that Southern Exposure look at its Real Estate Initiatives Report, which covers the changes the company has made in its subprime mortgage practices [see www.citigroup.com/citigroup/citizen/consumerfinance/data/li200212.pdf].

However, in response to questions from Southern Exposure, CitiFinancial did issue a general defense of the company’s practices:

On Predatory Lending and Citi’s Commitment to its Customers

“CitiFinancial opposes predatory lending. CitiFinancial supports efforts to provide credit to individuals with less than perfect credit history—oftentimes those who need it most—enabling them to pay for emergencies, pay for education, better manage their finances through bill consolidation, and establish a strong credit record for the future. These customers are often working people like teachers, firemen, nurses and secretaries who simply need access to credit. Our customers come back to us time and again because they like our service, our people and our product; it’s a very personal decision for them.”

On Citi’s Reform Efforts

“CitiFinancial has raised the bar in the consumer finance industry by making significant changes in its lending practices since acquiring The Associates in 2000. We eliminated single premium credit insurance on real estate secured loans, we required our brokers to adhere to strict standards, we implemented a referral-up program, we reduced the maximum number of points charged on real estate secured loans to three from five and we enhanced our closing procedures to make the process more clear and customer friendly. “We have ongoing, constructive dialogue with advocacy groups, regulators and elected officials. We appreciate the feedback as we continue to make changes as appropriate.”

In May, Citi announced it had reached a peace pact with the National Training and Information Center (NTIC), a Chicago-based advocacy group that had previously been a harsh critic. Under the agreement, NTIC will review the progress of CitiFinancial’s reform initiatives and work in partnership with the company to “promote affordable mortgage product solutions for customers.”

In a prepared statement, CitiFinancial said: “Input from consumer groups such as NTIC has contributed to our efforts to make a series of important changes to our lending practices over the past two years.”

NTIC added: “CitiFinancial has made tremendous progress. We now have the opportunity to affect change in a broader capacity within our communities. We are excited by the potential impact of this agreement.”

Tags

Michael Hudson

Mike Hudson is co-author of Merchants of Misery: How Corporate America Profits from Poverty (Common Courage Press), and is a frequent contributor to Southern Exposure. (1998)

Mike Hudson, co-editor of the award-winning Southern Exposure special issue, “Poverty, Inc.,” is editor of a new book, Merchants of Misery: How Corporate America Profits from Poverty, published this spring by Common Courage Press (Box 702, Monroe, ME 04951; 800-497-3207). (1996)