This article first appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 31 No. 2, "Banking on Misery." Find more from that issue here.

After the thaw of the Cold War, the global community ratified numerous treaties aimed at ending the nuclear arms race. Now the Bush Administration is quietly reversing course, promising a new generation of weapons that peace activists fear will uncork the nuclear genie they have worked long to contain.

“What DOE [the Department of Energy] wants is to produce nuclear weapons of new design,” says Lou Zeller, a researcher for Blue Ridge Environmental Defense League in North Carolina. “This would spark a new nuclear arms race.”

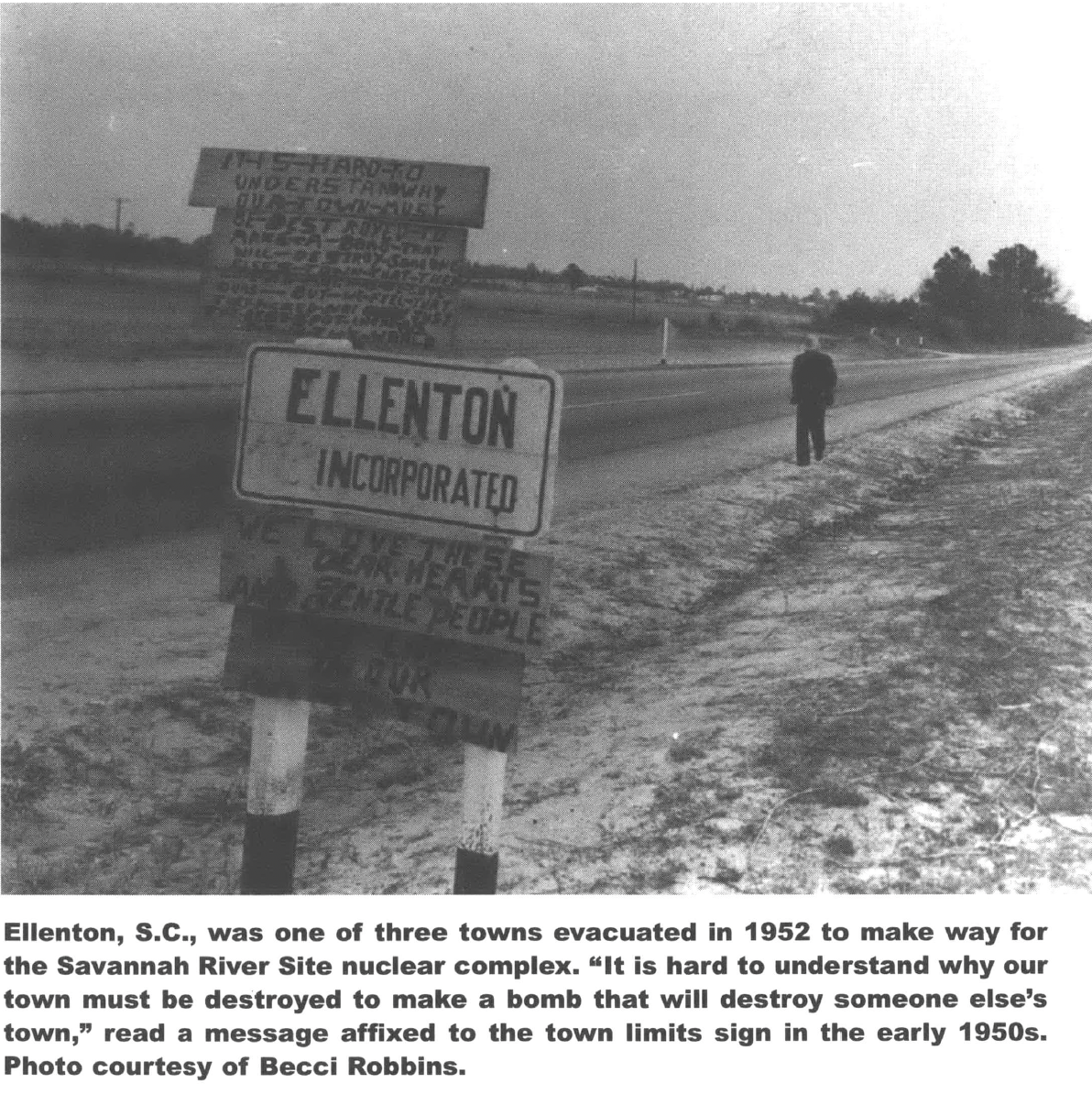

At issue is a DOE plan to build a new billion-dollar nuclear weapons factory at the Savannah River Site (SRS) in Aiken, S.C., a complex that occupies 312 square miles across the river from Georgia. The plant would manufacture plutonium pits, the core component for nuclear bombs. Since 1952, SRS has produced tritium and plutonium for weapons but has never assembled them.

Critics of the new pit plant argue that the project poses a risk to public safety, the environment, and national security. Greenpeace International nuclear campaigner Tam Clements called plans for the new bomb factory “ill-timed, unsubstantiated, and provocative.” He says the DOE has not provided evidence of the need for a new pit plant, and is relying on classified documents that were prepared and presented with no input from the public.

“As the role of nuclear weapons becomes ever harder to defend, DOE planners have set out to develop nuclear weapons as a first-strike, counter-proliferation weapon,” Clements says. “The DOE must publicly present solid policy and economic justification for this new facility. Reliance on Cold War jargon and secret, non-public documents is insufficient to make the case.”

The United States has a reserve of 13,000 to 15,000 plutonium pits and a current stockpile of about 10,700 warheads, according to Jim Bridgman of the National Alliance for Nuclear Accountability. But DOE officials say those pits begin to decay in as few as 45 years and that the United States’ supply will need to be replenished by 2020.

“Malarkey,” says Mary Olson, director of the Nuclear Information and Resource Service southeast office. She contends that the DOE’s claim of plutonium pits’ rate of decay has not been substantiated, and suspects it is simply a ploy to expand plutonium production. Olson further charges that the government’s assertion that the United States is the only nuclear power without the capacity to manufacture plutonium pits is false, as the Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico has the capability to do so.

Zeller says the new plant will not just replenish supplies but will allow SRS to build and upgrade new nuclear weapons. “We already have—for the foreseeable future—thousands of these weapons on hand, enough to blow up the world hundreds of times over.”

Plutonium pits were made at Rocky Flats, Colo., until 1989, when the plant was shut down after an FBI raid to investigate environmental crimes discovered massive contamination at the site.

The new plant in Aiken would adopt the same technology used at Rocky Flats. Critics want to know what will prevent the same costly outcome at SRS, already an Environmental Protection Agency Superfund site because of repeated accidents that have caused massive radioactive contamination. And given gloomy economic forecasts, opponents of the facility wonder how the government can honor its commitment to clean up SRS while spending billions of new dollars to expand operations. The new pit plant would cost up to $4 billion to build and $250 million to operate each year.

Clements says the way the Bush Administration is tackling that problem is by lowering environmental standards for cleaning up nuclear waste. These cost-cutting measures are called “rapid cleanup,” and allow SRS to cut comers in order to meet its obligations.

While the safety and environmental hazards posed by the new pit plant would have the greatest impact on the largely low-income population living near SRS, its construction has global implications. It signals that the United States intends to break its promise to seek nuclear disarmament as agreed to in the 1970 Non-Proliferation Treaty, which the Clinton Administration reaffirmed in 2000 as an “unequivocal commitment.”

But the congressionally mandated Nuclear Posture Review, released on December 31, 2001, revealed the new agenda of the Department of Defense and the DOE. The review calls for “a revitalized nuclear weapons complex” and “a new modern pit facility,” along with a new generation of low-yield, “bunker-busting” nuclear weapons that would be used to attack underground “terrorist” hideouts. Observers such as Jane Wales of the Center for Arms Control worry that the posture review presents “a vision for a new world in which nuclear use is ‘thinkable.’”

According to Olson, the nuclear establishment has long wanted to design and develop new nuclear weapons, and the changing political landscape has provided increasingly fertile ground for the weapons industry. “The seeds were planted a long time ago,” she says. “Now they’ve had an opportunity to sprout.”

Clements says the 9/11 attacks not only emboldened the Bush Administration to pursue expanded nuclear weapons production but also provided the cover to do so largely in secret. “September 11 was the exact excuse they needed to operate in the dark,” he says. Clements and other anti-nuclear activists say information is more difficult to obtain now, citing public documents that were removed from Department of Defense, Environmental Protection Agency, and SRS web sites in the months following 9/11.

While nuclear weaponeers use the threat of terrorism to justify ramping up U.S. nuclear capabilities, critics of expanding production at SRS fear that concentrating the nation’s plutonium at a single site puts the South square in the terrorists’ crosshairs. At a public meeting on March 27 in North Augusta, several speakers expressed concern about the area’s increased vulnerability to attack. “What better come-and-get-me signal could we give them than by having all the plutonium stored in one space?” asked Peggy Roche of Columbia.

Lawrence Kokajko of the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) responded, “We are aware of the terrorist threat and are sensitive to it.”

Not satisfied with NRC’s calculations regarding the risk to residents in the area, Brendolyn Jenkins, speaking on behalf of an Aiken community group, pressed for clarification. “What does NRC consider an acceptable number of fatalities?”

NRC spokesperson Tim Harris responded, “We have no hard and fast numbers.”

When asked to respond to the community’s fears of a potential terrorist attack, National Nuclear Security Association spokesperson Bryan Wilkes said in a recent email interview, “NNSA will have the highest levels of security at the pit facility when it opens. Terrorists strike at targets of opportunity. A highly secure facility like [SRS] will not be a good target for anyone. It’s why other sensitive facilities and places in the U.S. haven’t been attacked or penetrated, or even attempted.”

The pit plant is just the latest attempt to expand operations at SRS. Another project slated for the site is a reprocessing plant that would turn surplus plutonium into mixed oxide, or MOX, to fuel commercial reactors in the Carolinas. The DOE has marketed the proposal as a way to reduce the stockpiles of dangerous material the nuclear weapons industry generated during the Cold War and minimize the risk of it falling into the hands of terrorists.

That argument, Zeller says, has masked the industry’s true motivation. “The unspoken part of the MOX fuel project has always been that it is an attempt to create a plutonium economy,” Zeller says. “This is an attempt to reopen the door we shut 25 years ago.”

The irony has not escaped anti-nuclear activists that if both construction projects are approved, SRS will have one plant to dismantle nuclear weapons and another plant to create more.

“It used to be swords into plowshares; now it’s swords into swords,” says Don Moniak, who lives in Aiken and volunteers as a Blue Ridge Environmental Defense League consultant. His is a lonely job: Aiken is a conservative community with a long history of supporting SRS because of the jobs it provides and the money it has pumped into the state economy since its construction in 1950. SRS is South Carolina’s largest employer, with a current payroll of over $1 billion.

The MOX plant was shopped around to various sites across the country, but public resistance thwarted those construction proposals. The project finally found a home at SRS largely because the South is known as the path of least resistance for dangerous waste. But environmentalists and anti-nuclear activists say enough is enough. “We cannot let the South become the cradle of a new nuclear arms race,” Zeller says.

Zeller and others opposed to the construction projects slated for SRS have their work cut out for them. Critics of expanded plutonium production at SRS are greatly outnumbered and out-gunned by lobbyists paid by the nuclear industry and by a new administration bent on maintaining a hawkish military posture.

Still, these activists are cautiously optimistic that a sleeping public is waking up to a new reality. Moniak says the threat of a terrorist attack at SRS has generated a new level of interest in a subject that usually makes people’s eyes glaze. “It’s woken a lot of people up,” he says. “People used to think nuclear issues weren’t personally important to them. It’s a show-stopper for them now.”

Zeller has noticed a change as well. “People are calling us more, showing up at hearings more. It’s still an uphill battle, and industry still holds most of the cards, but we’re getting information out and I think it’s having an effect. We don’t want to scare people, but it’s a scary situation and I think it’s only fair to warn people.”

Clements says the threat of terrorism is a legitimate concern, but what alarms him even more is the signal the Bush Administration is sending to the world. “Instead of reducing reliance on nuclear weapons, we are moving to stockpile more far into the future. We have far too many people trying to find the bad guy over there instead of trying to find the good guy here at home.”

Tags

Becci Robbins

Becci Robbins is a freelance writer living in Columbia, S.C. (2003)