This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 31 No. 1, "Hidden Casualties." Find more from that issue here.

She’d seen too much, choked down her anger for too long. She couldn’t hold the song inside her any longer.

Florence Reece was 30 years old the year the men went on strike, and she saw the blood and starvation that came with it. She saw the hungry little ones, with tiny legs and stomachs swollen from eating green apples. And she saw the coal company’s “gun thugs” roll up to her cabin, four or five carloads of them outfitted with their cartridge belts and high-powered rifles.

They were deputies in the employ of the man who held the tide of high sheriff, John Henry Blair, but their wages were paid by the company and their job was to root out union men like her husband, Sam, who was organizing the others to fight for decent wages and working conditions.

“They kept harder and harder a-pushin’ us,” Florence Reece would recall. “I said, ‘There’s nothing in here but a bunch of hungry children.’ But they come in anyway. They hunted, they looked in suitcases, opened up the stove door, they raised up mattresses. It was just like Hitler Germany.”

She didn’t have any paper, so she tore a page off a wall calendar, and started writing. In that moment of near-despair, she created a song that bristled with outrage and defiance.

They say in Harlan County

There are no neutrals there,

You’ll either be a union man

Or a thug for J.H. Blair

The verses simply set up the refrain—the question that, in that place and time, had to be answered.

Which side are you on?

Which side are you on?

It was a challenge, it was a demand, and it was the question that drove the song, gave it a name and made it, in decades to come, the anthem of Appalachian coal miners who rose up to fight poverty and exploitation.

Florence Reece, a coal miner’s wife struggling to feed eight children and keep her husband alive, wrote the song in 1931, in the midst of a blood-soaked, two-year strike in Harlan County, Ky. The song spread well beyond Bloody Harlan. It’s been sung at union rallies in mountain hollows, at folk concerts among the urban bohemians, in civil-rights marches along hostile highways, on the green lawn of the U.S. Capitol, in the movies, and in Great Britain, China, and other far lands.

“It’s part of our history now,” says Hazel Dickens, a folk-singing luminary who grew up in Montcalm, W.Va., just over the border from Tazewell County, Va. “You hear it everywhere.”

Just as “We Shall Overcome” made itself the anthem of the American civil-rights movement, “Which Side Are You On?” became the most memorable of the rich procession of protest songs that came out of the Southern Appalachians.

“In a lot of ways, that song distills everything to its essence,” says Stephen Mooney, a professor of English and Appalachian studies at Virginia Tech. He first heard the song in the 1970s, as a teenager tagging along at strike rallies in his native Dickenson County. “I remember thinking how damn cool it was that there were songs that were by my people and were about what had happened to my people.”

Men died in explosions and rock falls. Families starved as coal booms turned bust. Companies hired private armies, evicted families, and harassed men who tried to organize unions. Miners retaliated and company gunmen and unionists waged small, bloody civil wars along mountain ridges and hollows.

These grievous conflicts in the late 19th century and the first half of the 20th inspired a legion of songs, as have the battles that continue today over union contracts, strip mining, and health and safety hazards underground. The coalfields’ literature of song includes Aunt Molly Jackson’s “Kentucky Miner’s Wife (Ragged Hungry Blues)” in the 1930s, Merle Travis’ “Sixteen Tons” in the 1940s, and Steve Earle’s “Harlan Man” in 1999.

Reece’s union anthem stands out from the rest. Mooney notes that Ralph Chaplin’s 1915 song, “Solidarity Forever,” had broader fame in the 20th century American labor movement. But while it was written about a West Virginia coal strike, Chaplin was a Kansan raised in Chicago, and Reece’s song became more intimately identified with Appalachia’s coal wars.

Reece’s creation, set to a Baptist hymn, “Lay the Lily Low,” took a circuitous route to its place in the region’s history and culture. Around 1940, a young folksinger, Pete Seeger, heard it from a miner living in New York City. In 1941, Seeger and his band, the Almanac Singers, recorded it and carried the song to a larger public.

Still, by 1947, Seeger was to recall, the song seemed almost forgotten in the coalfields. It was known in Manhattan’s Greenwich Village, “but not in a single miner’s union local.” In time, that would change.

Every social movement needs an anthem. Seeger, Guy and Candie Carawan, the Freedom Singers, and other political troubadours provided the soundtrack for the upheavals of the 1960s. “We Shall Overcome” had been a union song before it was adopted by civil-rights workers. “Which Side Are You On?” also made the crossover.

The leader of the Freedom Riders, James Farmer, was in Mississippi’s Hinds County Jail when he rewrote “Which Side Are You On?” He hoped to bolster local blacks who had been silenced by violence and economic reprisals, in a state where the governor, Ross Barnett, vowed to fight integration to the end.

They say in Hinds County

No neutrals have they met

You’re either for the Freedom Riders

Or you “tom” for Ross Barnett

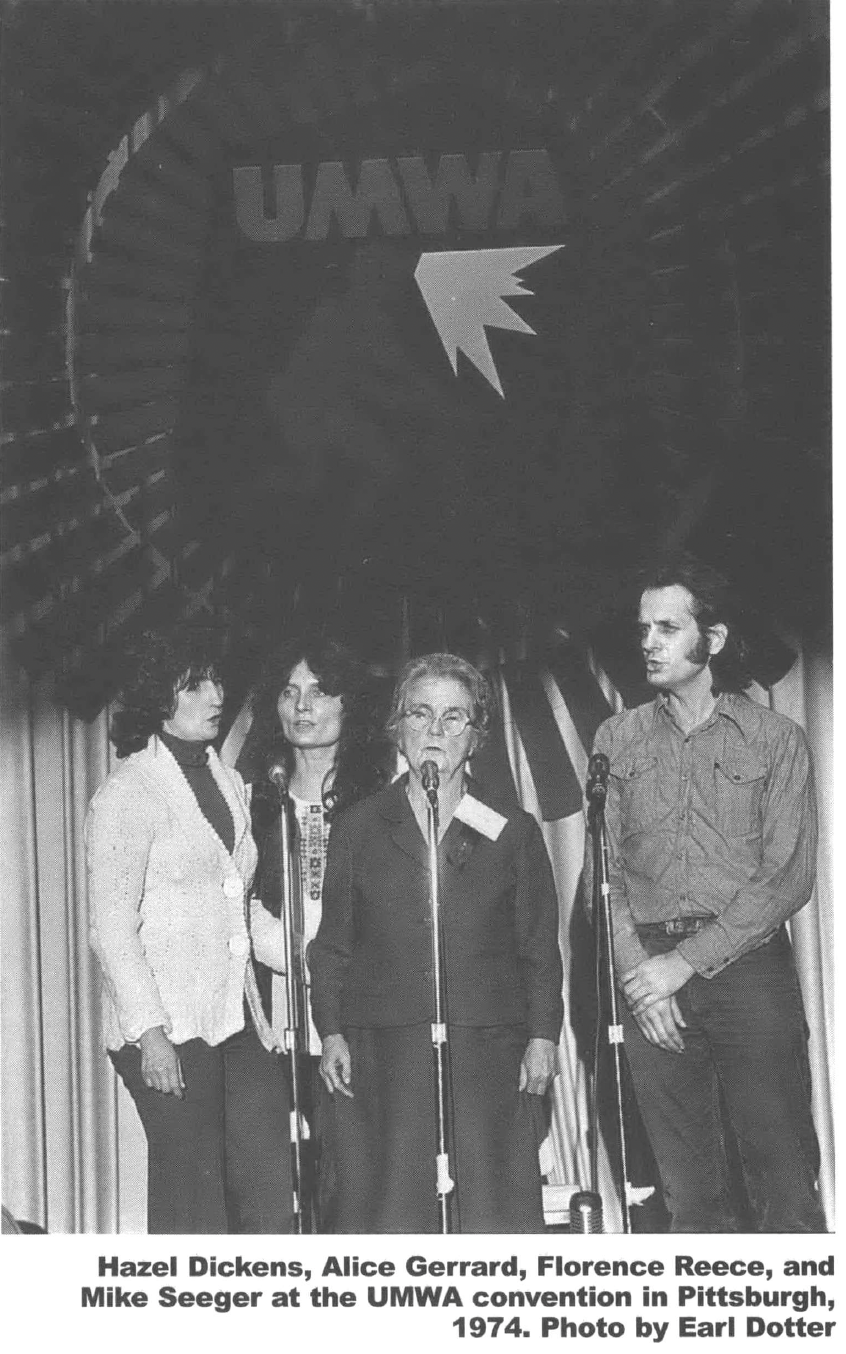

Great battles were unfolding, too, in the Appalachian coalfields. Florence Reece was in the middle of the struggles, aging but feisty. In 1974, when the United Mine Workers went on strike in Harlan County, Reece was there, returning to Kentucky from her home in Tennessee. She sang her famous song in a raspy voice and urged exhausted union families to stand together for the UMWA—a moment preserved on film in an Oscar-winning documentary, Harlan County USA.

Many people had sung the song by then, including Hazel Dickens (see page 46), who performed on the documentary’s soundtrack and at union rallies whenever she was needed.

She liked the song because it was personal as well as political, a plaintive cry that rose from real life rather than grand ideologies. Dickens could picture the scene in her mind: Sam Reece hiding in the hills, Florence Reece back at home with eight starving and frightened children huddling around her as the company men busted in.

“All because they wanted a decent wage and to be treated right. That’s all they wanted—the basics,” Dickens says. “I’m sure when she wrote it she had absolutely no idea that anybody would ever sing it. She just had to do something.”

Dickens got to know Reece as they both sang for the union. “She was kind of like a mother to everybody,” Dickens recalls. “The young people gathered around and listened to her. They sort of reminded me of feeding birds: eyes wide open, just standing there holding on to every word she said.”

Florence Reece died in 1986, at age 86, dedicated to the union cause until the end.

In the last years of her life, her song gained new fame through the work of Billy Bragg, an emerging English pop star who had undergone a political awakening during Great Britain’s titanic coal miners’ strike. It was during those intense months of 1984 that Bragg first heard “Which Side Are You On?”

“Everybody was singing it,” he recalls, and he was struck by the “continuity of struggle” it represented—the sense “that this is not the first time that any of these things have happened to people, that sense that you’re not struggling alone.”

He “took stuff out of the newspaper, stuff that was happening, stuff that was there on the ground” and adapted Reece’s song to his own country and his own time.

The government had an idea

And Parliament made it law

It seems like it’s illegal

To figh tfor the union anymore.

He put it on his four-song EP recording of protest songs. The EP zoomed up the charts in England, something that would have been unthinkable in America, where big record labels and radio stations prefer to avoid politics.

Five years later, when thousands of Virginia miners went out on strike against Pittston Coal Co., Bragg was drawn to the confrontation. In the fall of 1989, he visited the UMWs Camp Solidarity in Russell County and toured the southeastern United States, putting on concerts to raise money for the strikers.

Dickens did her part, too. She sang at a benefit in New York City with Pete Seeger and at a rain-muddied rally in Southwest Virginia. And she joined Bragg in Chapel Hill, N.C., to raise $5,000 for the miners in a show chronicled in a Billy Bragg documentary that took its name from the tide of Reece’s song.

As the concert ended, a group of union men and women, wearing the green camo shirts that had become the UMW’s strike uniform, stood on stage with Dickens and Bragg to sing “Which Side Are You On?” Dickens included a verse tailored to the fight that had brought them together.

Well down in Russell County

No neutrals can be found

You’ll either be a union man

Or one of them Pittston clowns.

The song that poured out of Florence Reece generations ago has crossed over, evolved, and endured. It never gained the fame of “We Shall Overcome,” but people are still working to keep it alive in a new century.

Mooney, the Virginia Tech professor, has his students study the song as they explore their Appalachian roots. An American folk-punk band, the Dropkick Murphys, covers the song in its album, “Sing Loud, Sing Proud.” The song turns up, too, in a new documentary, Hazel Dickens—It’s Hard to Tell the Singer from the Song.

Still, Dickens hasn’t had many chances to sing it the past few years. The labor movement has been undercut by an anti-union axis in government and business. Union rallies don’t come as often as they once did.

Dickens would like to see more workers fighting shoulder-to-shoulder, acknowledging their common identity as members of the overburdened and underpaid. She’d like to hear people singing the words Florence Reece wrote on a page ripped from a wall calendar.

Which side are you on?

“I think we might need another movement,” Dickens says. “We need other people out there singing these songs.”

To learn more about “Which Side Are You On?” and Appalachian labor struggles, see these books, music albums, and videos, many of which were helpful in writing these stories.

Books

Guy and Candie Carawan, Voices from the Mountains

John W. Hevener, Which Side Are You On? The Harlan County Coal Miners, 1931-39

Kathy Kahn, Hillybilly Women

Music albums

Billy Bragg, Back to Basics

Hazel Dickens, Hard Hitting Songs For Hard Hit People

Hazel Dickens, Sarah Ogan Gunning, Phyllis Boyens, and the Reel World String Band, Coal Mining Women

Hazel Dickens—It’s Hard to Tell the Singer from the Song

O Sister! The Women’s Bluegrass Collection

O Sister! 2 A Women’s Bluegrass Collection

Videos

Harlan County USA

Which Side Are You On? Billy Bragg Goes to Moscow and Norton, Virginia Too

Hazel Dickens—It’s Hard to Tell the Singer From the Song

Hazel Dickens video and music available at www.appalshop.org; more bluegrass music available at www.rounder.com.

“Which Side Are You On?”

By Florence Reece

Come all of you good workers

Good news to you I’ll tell

Of how that good old union

Has come in here to dwell

Chorus

Which side are you on?

Which side are you on?

Which side are you on?

Which side are you on?

My daddy was a miner

And I’m a miner’s son

And I’ll stick with the union

Till every battle’s won

They say in Harlan County

There are no neutrals there

You’ll either be a union man

Or a thug for J.H. Blair

Oh, workers can you stand it?

Oh, tell me how you can

Will you be a lousy scab

Or will you be a man?

Don’t scab for the bosses

Don’t listen to their lies

Us poor folks haven’t got a chance

Unless we organize

This is just one version of Reece’s union anthem. She penned other verses and many other songwriters and activists have written their own verses to go with the refrain’s uncompromising question.

Tags

Michael Hudson

Mike Hudson is co-author of Merchants of Misery: How Corporate America Profits from Poverty (Common Courage Press), and is a frequent contributor to Southern Exposure. (1998)

Mike Hudson, co-editor of the award-winning Southern Exposure special issue, “Poverty, Inc.,” is editor of a new book, Merchants of Misery: How Corporate America Profits from Poverty, published this spring by Common Courage Press (Box 702, Monroe, ME 04951; 800-497-3207). (1996)