Who Counts the Votes?

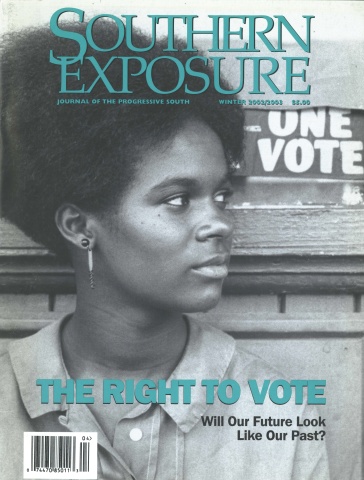

This article first appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 30 No. 4, "The Right to Vote." Find more from that issue here.

A quick, two-part quiz on the 2002 mid-term elections: Who really won? And second: Can you prove it?

In 2000, Democrats blamed butterfly ballots and hanging chads — and the Supreme Court’s decision of how to deal with them — for Al Gore’s failed Presidential bid. Now, after the Republican sweep of the 2002 elections, charges are shooting through cyberspace that once again, voting technology is to blame for Democratic misfortune.

At issue is the rise of high-tech voting. In the wake of Florida’s 2000 mishaps, hundreds of voting jurisdictions nation-wide began the process of switching to touch-screen machines and other upgrades. But in the end it may be, as journalist Jonathan Vankin has put it, that “the real scandal is the voting machines themselves” — especially these new, computerized systems, which, it turns out, may be far more vulnerable to fraud and manipulation than old-style paper ballots.

It can be shockingly easy to tamper with vote counts on new machines. Software can be altered, subroutines slipped in by dishonest technicians to manipulate the vote in any way desired. Such fraud would be nearly impossible to detect, in large part because the companies that make the machines consider the code to be proprietary, and state and county officials are prohibited from examining it. Just as troubling, says voting technology expert Rebecca Mercuri, computer-administered elections can be much harder — even impossible — to check, audit, and recount, because systems increasingly record votes only electronically, eliminating paper trails. Without physical ballots to check, voters have no way of knowing whether machines are accurately casting their votes.

And the small number of companies dominating the field of computer-run elections are overwhelmingly connected to one party. As famed Texas journalist Ronnie Dugger, who wrote a pathbreaking investigation of electronic voting in the New Yorker in 1988, told Vankin, “The whole damn thing is mind-boggling. They could steal the presidency.”

Here are short profiles of the three most important voting-systems companies in the United States:

Election Systems and Software

By far the largest vote-counting company in the United States, Election Systems and Software (ES&S) of Omaha, Neb., was founded in 1980 by brothers Todd and Bob Urosevich. According to internet journalist Bev Harris of Talion.com, the company, originally known as American Information Systems, was controlled in the 1980s by the hard-right, fundamentalist-leaning Ahmanson family of California, heirs to the Home Savings of America fortune. In the nineties, the company could boast future U.S. Sen. Chuck Hagel (R-Neb.) as its chairman; Hagel still owns stock in the McCarthy Group, which currently has a stake in ES&S. Since ES&S enjoys an exclusive contract with the state of Nebraska and counts 80 percent of the state’s votes (the rest are hand-counted), Hagel is effectively part owner of the firm responsible for counting his own votes.

ES&S has been involved in voting-related scandals across the country, particularly in the South. In April 2002, Arkansas secretary of state Bill McCuen pleaded guilty to taking bribes and kickbacks in voting-machine scandals, part of which involved Business Records Corp. (BRC), now merged into ES&S. A BRC executive, Tom Eschberger, accepted immunity from prosecution in return for cooperating in the investigation, and has since become a Vice President of ES&S.

According to the Tallahassee Democrat, Sandra Mortham, Florida’s top election official from 1995 to 1999, lobbies for both ES&S and the Florida Association of Counties, which endorsed ES&S in return for a commission. Mortham herself received commissions for ES&S touch-screen machine purchased by Florida counties (see “The Re-Election of Jim Crow,” Southern Exposure Election 2002 Special Edition).

In another revolving-door scandal, the state of California has begun an investigation into Louis Dedier, the state’s director of voting systems. Dedier accepted a job with ES&S, then made recommendations without disclosing the potential conflict of interest.

Breakdowns and other problems have plagued ES&S machines since at least the late 1990s. When the company’s new ballot-reading machines malfunctioned in Hawaii in 1998, Tom Eschberger admitted there were difficulties, but protested to the Honolulu Star Bulletin that “in all fairness, there were 7,000 machines in Venezuela and 500 machines in Dallas that did not have problems.” However, during that same election season, the Dallas devices initially failed to count 41,000 votes. And two years later, massive breakdowns and technical difficulties with ES&S systems rocked the Venezuelan national elections, causing the vote to be suspended. Pres. Hugo Chavez and Venezuelan election officials accused the company of “trying to destabilize the country’s electoral process,” while protesters chanted “Gringos go home!” at ES&S technicians.

ES&S-related problems continued in 2002, as Bev Harris has documented:

• In the primaries, Union County, Florida, used ES&S machines for the first time. According to the Bradenton Herald, under old methods of hand counting, election workers usually finished tallying the county’s votes by the end of the day. This time, when a programming error corrupted the machine count, officials had to resort to the old method. Altogether the process took more than twice as long as manual counting.

• During early voting in Dallas County, Texas, voters complained that ES&S touch-screen devices were recording Democratic votes as votes for Republicans. Similar problems were reported in Florida.

• Twenty percent of ES&S machines in Tangipahoa Parish, Louisiana, malfunctioned on election day. According to the Baton Rouge Advocate, the state committee that chose ES&S ignored the wishes of local officials, who preferred another system.

• In South Dakota, a “defective chip” in one ES&S machine caused the double counting of some ballots.

• In Nebraska, a counting error and ballots printed too lightly for machines to read gave the false impression that a school bond issue had failed, when it had actually passed by a 2-1 margin. Officials blamed ES&S, which had supplied both machines and ballots.

• ES&S coding errors in Adams County, Nebraska, resulted in no votes being counted at all.

Sequoia Voting Systems

The second-largest voting systems provider in the United States, Sequoia is owned mostly by London-based De La Rue Cash Systems, “the world’s largest security printer and papermaker, involved in the production of over 150 national currencies,” as well as travelers’ checks and vouchers.

According to internet journalist Lynn Landes of EcoTalk.org, Sequoia has been “plagued by scandal.” In 1999, two Sequoia executives, Phil Foster and Pasquale Ricci, were indicted for paying Louisiana Commissioner of Elections Jerry Fowler an $8 million bribe to buy their voting machines. Foster’s ongoing legal troubles would later haunt the company, when Sequoia neglected to inform several Florida counties about his indictment. Indian River County voided a $2 million contract with Sequoia, and contracts with other counties were jeopardized. Indian River reversed itself only after a personal appearance by Sequoia’s CEO before the county commission.

In August 2002, a losing candidate in Boca Raton, Fla., city council elections wanted to have Sequoia voting machines examined by experts. But Palm Beach County Elections Supervisor Theresa LaPore (responsible for the infamous butterfly ballot) said that the contract with Sequoia, as well as state law, defined Sequoia’s equipment and programming as “trade secrets,” shielded from public scrutiny. Also, any tampering by non-Sequoia technicians would void the machines’ warranties.

Diebold Inc.

Ohio-based Diebold Inc. may not be the leader in election technology today, but it shows every sign of dominating the market of the future. Not bad for a company that just three years ago had never built a voting machine.

Diebold’s roundabout entry into elections came in 1999, when the company — the nation’s leading maker of ATM machines, where it now corners 66% of the U.S. market — bought a Brazilian ATM maker for $240 million. The Brazilian company was also in charge of upgrading that country’s voting machines, and Diebold set about blanketing Brazil with 355,000 touch-screen voting terminals, including generator-operated vote-counters rafted into the heart of the Amazonian rainforest in the most recent presidential contest.

In January of 2002, Diebold’s election division — Diebold Election Systems — bought its way into the U.S. market as well, acquiring the failing Global Election Systems for $24 million. Forbes reports that heavy lobbying led to contracts in California, North Carolina, and most notably Georgia, which in March 2002 announced it was contracting Diebold for $54 million to install touch-screen systems in all of Georgia’s 159 counties.

With this year’s passage of Congressional legislation granting $3.9 billion to states for, among other things, upgrading election technology, Diebold is now anticipating $1.5 to $2 billion in revenues for filling the national touch-screen niche.

Diebold maintains close ties to the other leading voting machine companies. Diebold’s current president, Bob Urosevich, was the co-founder of American Information Systems with brother Todd Urosevich, who is now Vice President of Election Systems & Software (see above).

Furthermore, former Diebold executives Howard Van Pelt and Larry Ensminger are now top managers at Advanced Voting Solutions (formerly Shoup Voting Solutions). Shoup/AVS has a checkered past in the elections business; Lynn Landes notes that Shoup officers were indicted for bribing politicians in Tampa, Florida, in 1971, and company founder Ransom Shoup was convicted in 1979 of conspiracy and obstruction of justice in a FBI election-machine inquiry in Philadelphia.

The Diebold corporation is heavily political, and heavily favors the Republican Party. Since 2000, the company itself has made $170,000 in political contributions — all to the Republican National State Elections Committee.

Diebold’s corporate directors and officers are similarly clear in their political sympathies. Longstanding and generous friends of the Republican Party such as Louis Bockius III, Donald Gant, and Eric Roorda populate the board of directors.

According to campaign finance records at OpenSecrets.org, of the over $240,000 given by Diebold’s directors and chief officers to political campaigns since 1998, all has gone to Republican candidates or party funds.

Diebold’s clear political sympathies are cause for scrutiny. Yet for the rising star of the voting technology world, prospects of cornering the elections market may trump ideology. In Brazil’s presidential elections this year, many political analysis credit Diebold’s extensive voting-machine installation with helping elect Luiz Inacio “Lula” da Silva, leader of the left-wing Workers’ Party.

Tags

Gary Ashwill

Chris Kromm

Chris Kromm is executive director of the Institute for Southern Studies and publisher of the Institute's online magazine, Facing South.