Of Two Minds About Voting

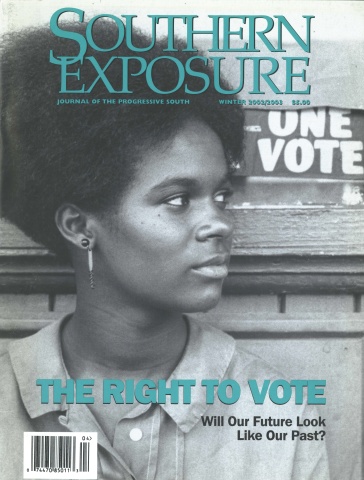

This article first appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 30 No. 4, "The Right to Vote." Find more from that issue here.

I’m a 24-year-old African American student who lives in Raleigh, North Carolina’s capital and one of the wealthiest cities in the state.

At this point in my life, it’s really hard for me to gauge just how I feel about elections.

After having volunteered to work on a city council campaign last year, I haven’t seen any real change in my city. I’ve kind of turned a deaf ear to voting.

That’s not to say that I’ve stopped voting. As long as there are still elections in America, I intend to be at the polls. In this nominally democratic society, voting is a basic civil right, and too many of my people had to fight and die for the franchise for me to abstain.

But I see very clearly that elections don’t make much of a real difference in my everyday life. They haven’t helped my pursuit of a college education any easier. They haven’t helped my two developmentally disabled sisters that my mother takes care of find any life skills training.

I vote at a relatively affluent precinct in northwest Raleigh, in the Lake Boone/Crabtree Valley area. The majority of people in this area are high-income, highly educated folks — tech sector people and professionals, retirees. It’s also mostly white. My family is the antithesis of this. There are four of us living in a black low-income household. Only my mother and I are registered to vote. We don’t have a car, so in order to get to the polls every election, Mom and I rely on rides from Democratic Party volunteers. If we didn’t have this, we’d be up shit creek. Our polling place (Glen Eden Pilot Park) is too far from the nearest bus stop.

When we go to the Park to vote, we don’t experience the horror stories we hear about in other counties and states. The poll workers never ask us for proof of our registration. They offer assistance without us asking. The inside of the place is clean, well-lit, and organized. I note that my fellow voters are white and appear well-to-do, well-educated, confident, and cheerful.

They also, from what I can see, are politically literate. They are generally moderate to conservative in their views. I know this from overhearing conversations. They do not seem apathetic. They feel they have a stake in the system — although they don’t come out for the primary races. Mom and I, we never miss an election. And I’m not sure if we have a stake or not.

This creates a gnawing disconnect between voting in elections and the social, economic, and political reality of my everyday life. My life may have been affected by elections in the six years that I’ve been voting, but not directly, not on the level where I can see it.

Our stake might be showing up because we can. Just 35 years ago I might not have even had this right. So I show up, even though I find the whole damn business of elections mind-numbingly boring.

My heart is deeply engaged instead in my day-to-day battles. I struggle with having enough money, food, and clean clothes to make it to school every day. I go to classes at Wake Technical Community College 17 hours and five days a week. I have to carry heavy textbooks that can weigh 15 to 20 pounds around with me for 11 hours a day, all because I don’t have a car to put them in between classes. I study and do homework every night and weekend and never finish, because it’s too much damn work for one person. I’m trying to graduate from that Godawful Wake Tech by May, because I’m getting sick and tired of having to spend three hours out of every day on our crappy Raleigh busing system and Wake Tech’s sorry-ass one-trip-every-hour bus running back and forth between that campus in the boondocks and my house. I have dreams and goals of being a writer and historian, but I’m often too goddamn tired at the end of the day to work on my craft. I’m trying to hurry up and finish my bachelor’s degree, because it’s the only way that I’ll ever have a snowball’s chance in hell of supporting my family and myself.

As you can see, I have too many things going on in my life to worry about the minute details of voting and the electoral process. There’s enough socioeconomic struggle taking place right in front of me; tangible, up-to-the-minute struggle that matters to my life. Elections? I don’t need to make a choice between two financially pre-selected candidates to participate in society. There’s a struggle taking place right in front of me; tangible, up-to-the-minute, life and death struggle.

There are no abstractions. I guess it is that way for most African Americans, especially here in the South. When I’m in school or just on the street, I don’t hear folks talking about elections. Of course everyone remembers the scandal in Florida during the 2000 Presidential elections, when thousands of African-American voters were intentionally purged from the registration rolls just prior to Election Day. We can recall the very scant coverage the mainstream American media gave to the fiasco, and the uphill battle that was faced by those people who were affected and their advocates to seek some kind of redress.

But I risk assuming too much when I say “we,” for “we” almost always refers to those who follow politics and national affairs regularly — in other words, so called “conscious” folks. Between that time and now, I scarcely recall many everyday black folk on the streets of Raleigh who had anything to say about the crisis, or who even knew what was going on. In the African-American community, what matters are low wages, inadequate public transit, abusive cops, high-priced housing and childcare, and degenerating public schools.

Does that mean I don’t go to the polls? It’s not an either-or proposition. My folks fought too damn hard and for too damn long for me to sit at home on Election Day.

The right to vote is central to any person in an allegedly democratic society. That’s why I choose to vote. It is essential to the exercise of citizenship. For too long, women and African Americans were denied this assertion of citizenship. Withholding the franchise was the clearest message that the misogynistic, white supremacist powers-that-be could send to the people denied this right. The de facto prohibition of this right today serves the exact same purpose, but more covertly, and more insidiously.

It’s like this: those that would reinstate another system of race-based apartheid, because of their unlimited wealth and privilege, have both the ideology and the means to launch a virtually unhindered campaign. There are an infinite number of means with which to orchestrate this attack, but by far the quickest and most advantageous way is through our electoral system.

Are we legitimizing the system when we vote? Maybe. Do we back off and withdraw from the gains for which people suffered and died? Absolutely not! We stay in, and we fight through. Even when we don’t see the result. Even if they spin it to legitimize themselves. Because we are going to challenge their legitimacy precisely by participating, and when participation proves to those who don’t yet understand that we have no intention of ceding what power we do have, it is then that we take it to the streets.

Tags

Yolanda Carrington

Yolanda Carrington is an activist and writer who lives in Raleigh, N.C. (2003)