The State of Voting

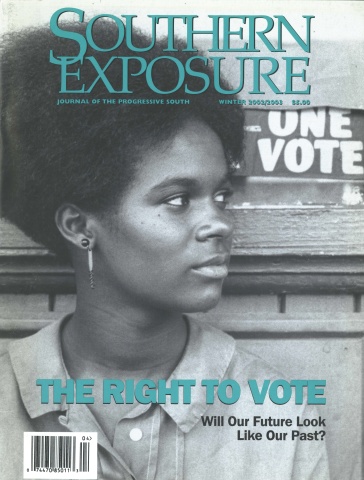

This article first appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 30 No. 4, "The Right to Vote." Find more from that issue here.

In December of 2000, the momentum for voting reform appeared unstoppable. Just a month before, a presidential election had been held in the balance due to Florida’s butterfly ballots, hanging chads, and other election system breakdowns. Dozens of studies and blue-ribbon panels soon followed, documenting a litany of barriers to voting across the country and proposing sensible reforms to restore democracy.

The momentum was not to last. Election reform soon fell off the public and political radar. Calls for voting rights were displaced by the “war on terror.” Electoral reform legislation languished in Congress. State-level steps to overhaul voting systems ran up against legislatures facing historic budget shortfalls in a faltering economy. Some improvements were made; many initiatives, however, passed without money earmarked to implement them, amounting to unfunded mandates.

So now, more than two years after Florida, where do we stand? To answer this question, Southern Exposure and the Institute for Southern Studies, publisher of SE, looked at the major voting problems identified in the avalanche of studies and commission reports released after the 2000 elections, and took stock of what has — and hasn’t — been done to address these issues.

We identified 10 key yardsticks for measuring the electoral health of each state. We then assigned a grade, based on how each state measured up to the national average and met basic standards required to conduct free and fair elections.

The findings are illuminating — and suggest that our nation’s election systems remain in critical condition:

Voter Registration: Voters face numerous obstacles to registering for elections. Over 30% of the U.S. population — 56 million eligible Americans — weren’t registered in 2000. Furthermore, being registered doesn’t guarantee a citizen will be able to vote. The Federal Elections Commission admits that in the 2000 presidential elections, problems with voter rolls kept 1.3 million registered voters from voting. While some progress has been made in state registration systems, many still fail to keep statewide, integrated voter records.

Provisional Ballots: The impact of poor registration systems is compounded by the fact that many states do not allow residents to vote “provisionally” if, for whatever reason, their names don’t appear on the voter rolls. As a result, many voters get unjustly turned away from the polls.

Uncounted Votes: Florida’s butterfly ballots and faulty punch-card machines brought national attention to the problem of outmoded voting equipment. A Caltech/MIT study found that in 2000, up to two million “residual votes” were cast but not counted — largely as a result of machine failures. A handful of states, including Florida and Georgia, have made upgrading machines a priority — but lack of state funds has slowed implementation.

Disenfranchised Felons: Laws that keep people with felony convictions from voting — which in the late 1800s served primarily to block political access to African Americans — vary across the country. Eight states, largely in the South, strip ex-felons of voting rights even after they’ve fully completed their sentences. Over four million citizens are denied the vote due to felony convictions, representing over two percent of the U.S. voting population — and over six percent of the African-American population. No states have lifted this barrier to democracy since 2000, and some have increased restrictions.

Efforts at Reform: Despite widespread calls for electoral reform in the wake of the 2000 elections, few states have made significant progress. Indeed, as the political watchdog group Common Cause noted in a 2001 follow-up report, “Very little has been done to restore confidence in the fundamental civil right to participate fully in our elections. . . . Most states made no improvements. A few even regressed.”

In the fall of 2002, the U.S. Congress passed a $3.9 billion package to assist states in upgrading voting machinery and setting standards for uniform voter registration lists. If passed by the Senate, it would also require states to provide provisional ballots. Critics charge that on the downside, it would increase voter identification requirements that may depress turnout.

The bill addresses roughly half of the indicators assessed in this report, while ignoring issues such as felon disenfranchisement, the need for voter education, and disclosure of campaign finances.

Despite the efforts that have been made for reform, our country still needs a complete overhaul to ensure a basic level of functioning and guarantee political access to all U.S. citizens. Such an overhaul will require a substantial investment of energy and resources. But a democracy requires nothing less.