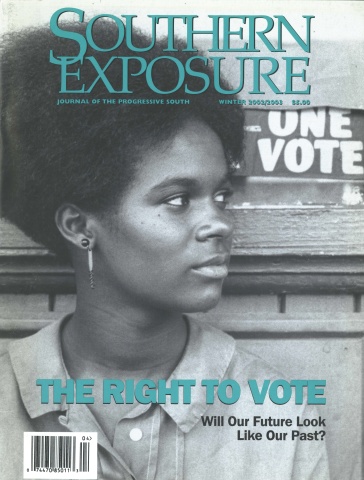

This article first appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 30 No. 4, "The Right to Vote." Find more from that issue here.

Alexander Keyssar’s The Right to Vote: The Contested History of Democracy in the United States (Basic Books, 2000, paperback 2001) is the first comprehensive history of the right to vote in the United States to be published since World War I. In it, Keyssar chronicles the evolution of the franchise throughout the United States from the era of the American Revolution to Election 2000. In so doing, he explores the links between various voting rights issues (e.g. class and race), and compares developments in different regions.

Widely acclaimed, The Right to Vote received the Beveridge Award from the American Historical Association (for the best book in American history) and the Eugene Genovese Prize from The Historical Society (also for the best book in American history). It was also a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize and for the Los Angeles Times Book Award.

For this essay, the author has specially adapted and combined several excerpts from The Right to Vote to create a brief (and necessarily incomplete) history of voting rights in the South.

From Republic to Democracy

At its birth, the United States was not a democratic nation — far from it. The very word democracy had pejorative overtones, summoning up images of disorder, government by the unfit, even mob rule. In practice, moreover, relatively few of the new nation’s inhabitants were able to participate in elections: among the excluded were most African Americans, Native Americans, women, men who had not attained their majority, and adult white males who did not own land. Only a small fraction of the population cast ballots in the elections that elevated George Washington and John Adams to the august office of the presidency.

To be sure, the nation’s political culture and political institutions did become more democratic between the American Revolution and the middle of the nineteenth century. This was the “age of democratic revolutions,” the epoch that witnessed the flourishing of “Jacksonian democracy.” The ideal of democracy became widespread during these years, the word itself more positive, even celebratory. Owing in part to these shifting ideals and beliefs — and also because of economic and military needs, changes in the social structure, and the emergence of competitive political parties — the franchise was broadened throughout the United States. By 1850, voting was a far more commonplace activity than it had been in 1800.

Yet the gains were limited. Longstanding historical labels ought not obscure the restricted scope of what was achieved. The American polity may have been set on an unmistakably democratic course during the first half of the nineteenth century, but the United States in 1850 stood a long way from “universal suffrage.” Significantly, that phrase had begun to appear in public discourse, but the institution lagged far behind. Indeed, some Americans who had been enfranchised in 1800 were barred from the polls by mid-century. Change was neither linear nor uncontested: the sources of democratization were complex, and the right to vote was itself a prominent political issue throughout the period.

Between 1800 and the early 1850s, most states, north and south, dropped their property and taxpaying requirements for voting. They did so for complex reasons and often under pressure. In the northern states, with the notable exception of Rhode Island, economic qualifications for voting were eliminated before industrialization had advanced very far; this had the unintended consequence of permitting industrial workers to vote when, decades later, they became numerous.

In the South, the issue had an added twist: enfranchising all white Southerners was a means of making sure that poor whites would serve in militia patrols guarding against slave rebellions. However much diehard reactionaries such as John Randolph of Virginia might have feared that broader suffrage would unravel the fabric of slave society, there were other political leaders who believed that it would contribute to white solidarity. A delegate to Virginia’s convention pointedly noted that “all slave-holding states are fast approaching a crisis truly alarming, a time when freemen will be needed — when every man must be at his post.” Was it not then “wise . . . to call together at least every free white human being and unite them in the same common interest and Government?”

In Europe (and elsewhere), resistance to universal suffrage was grounded not only in opposition to the enfranchisement of industrial workers but in an equally powerful opposition to the extension of political rights to the peasantry — to the millions of men, many of them illiterate, who lived in poverty, toiling on farms large and small. The American peasantry, however, was peculiar: it was enslaved. As Benjamin Watkins Leigh observed at Virginia’s constitutional convention of 1829, “slaves, in the eastern part of this state, fill the place of the peasantry of Europe.” “In every civilized country under the sun,” Leigh argued, “some there must be who labor for their daily bread” and who were consequently unfit to “enter into political affairs.” In Virginia and throughout the South, those who labored for their daily bread were African-American slaves — and because they were slaves, they never became part of the calculus, or politics, of suffrage reform. When the political leaders of Virginia or North Carolina or Alabama decided to abolish property or taxpaying qualifications, they did not remotely imagine that their actions would enfranchise the millions of black men who toiled on the cotton plantations and tobacco farms of the region.

In both the South and the North, thus, economic barriers to enfranchisement were dropped in social and institutional settings that permitted political leaders to believe that the consequences of their actions would be limited, far more limited than they would have been in Europe. The relatively early broadening of the franchise in the United States was not simply, or even primarily, the consequence of a distinctive American commitment to democracy, of the insignificance of class, or of a belief in extending political rights to subaltern classes. Rather, the early extension of voting rights occurred — or was at least made possible — because the rights and power of those subaltern classes, despised and feared in the United States much as they were in Europe, were not at issue when suffrage reforms were adopted. The American equivalent of the peasantry was not going to be enfranchised in any case, and the social landscape included few industrial workers. What was exceptional about the United States was an unusual configuration of historical circumstances that allowed suffrage laws to be liberalized before men who labored from dawn to dusk in the factories and the fields became numerically significant political actors.

Race, Reconstruction, and Jim Crow

The Civil War refocused the national debate about suffrage. Most obviously, four years of armed conflict, as well as the challenge of reconstructing the nation after the war, brought the question of black voting rights to the foreground of national politics. As important, the process of wrestling with the issue of black enfranchisement raised critical questions, largely ignored since the writing of the Constitution, about the role of the federal government in determining the breadth of the franchise. Although political leaders eventually drew back, they veered remarkably close to a profound transformation of the principles shaping the size and composition of the nation’s electorate.

At the outset of the war, only five states, all in New England, permitted blacks to vote on the same basis as whites; a sixth, New York, enfranchised African Americans who met a property requirement. Not surprisingly, the Civil War unleashed new pressures to abolish racial discrimination. The abolition of slavery turned four million men and women into free citizens who had a new claim on political rights; African Americans were loyal supporters of the Union cause and the Republican Party; they also had fought and died to preserve the Union, in considerable numbers. Indeed, by 1865, the traditional argument that men who bore arms ought to wield the ballot was applicable to more than 180,000 blacks. As General William Tecumseh Sherman himself noted, “when the fight is over, the hand that drops the musket cannot be denied the ballot.”

Freedmen themselves, as well as northern blacks, asked for — and sometimes demanded — the right to vote: hardly had the war ended when freedmen throughout the South began to write petitions, hold meetings, and parade through the streets to press for an end to racial barriers to voting. In Wilmington, North Carolina, freedmen organized an Equal Rights League, demanding that blacks be granted “all the social and political rights” that whites possessed. In 1865, the highly politicized black community of New Orleans put together a widely participated-in mock election to demonstrate the strength of their resolve; in Maryland, blacks held conventions and marches to further their demands. Former soldiers, ministers, free blacks, and artisans all played prominent roles in this political activity, joined by thousands of others who insisted that suffrage was their right and their due. To African Americans, enfranchisement not only constituted a means of self-protection but was a critical symbol and expression of their standing in American society.

Despite intense opposition from the white South, the political dynamics of Reconstruction led to a pathbreaking series of steps by the federal government to override state control of the franchise and grant political rights to African-American men. At the center of these dynamics were conflicts that unfolded between Republicans in Congress and President Andrew Johnson and his (generally) Democratic supporters after the end of the Civil War. Johnson’s approach to the task of Reconstruction, begun in 1865, was to offer lenient terms to Southern states so that they could be restored quickly to the Union. Despite some early vengeful rhetoric, Johnson’s program demanded few reforms and virtually guaranteed that political and economic power in the South would remain in the hands of whites, including those who had supported the rebellion. Alarmed at this prospect and at the resistance of many Southern leaders to policies emanating from Washington, the Republican-controlled Congress began to formulate its own program in 1866. Although relatively few Republicans at that juncture advocated black enfranchisement, they did seek to guarantee the civil rights of blacks and promote greater racial equality in Southern society.

To further that end, the moderate majority of Republicans in Congress negotiated the passage of the Fourteenth Amendment in June 1866. A compromise measure, the amendment was designed to punish Confederate political leaders (by preventing them from holding office), to affirm the South’s responsibility for a share of the national debt, and to protect Southern blacks without arousing the racial fears of northern whites. Although denounced by some (but not all) Radical Republicans as too tepid, the amendment nonetheless altered the constitutional landscape. By declaring that “all persons born or naturalized in the United States” were “citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside,” the amendment at long last offered a national definition of citizenship and confirmed that blacks were indeed citizens. The amendment also prohibited states from passing laws that would “abridge the privileges or immunities” of citizens or deny them “the equal protection of the laws.”

In its direct references to suffrage, the Fourteenth Amendment was a double-edged sword. Since most congressional Republicans — whatever their personal beliefs — were convinced that northern whites would not support the outright enfranchisement of blacks, the amendment took an oblique approach: any state that denied the right to vote to a portion of its male citizens would have its representation in Congress (and thus the electoral college) reduced in proportion to the percentage of citizens excluded. The clause would serve to penalize any Southern state that prevented blacks from voting without imposing comparable sanctions on similar practices in the North, where blacks constituted a tiny percentage of the population. Although this section of the amendment amounted to a clear constitutional frown at racial discrimination, and Congress hoped that it would protect black voting rights in the South, the amendment, as critics pointed out, tacitly recognized the right of individual states to erect racial barriers. Wendell Phillips sharply attacked the amendment for this very reason, calling it a “fatal and total surrender.” Of equal importance to many, the use of the word male constituted a de facto recognition of the legitimacy of excluding women from electoral politics.

However tepid or double-edged the Fourteenth Amendment may have been, it was fiercely opposed by President Johnson, white Southerners, and northern Democrats. Meanwhile, the state governments that Johnson had sponsored in the South legally codified various forms of racial discrimination while doing little to stop campaigns of violence against blacks and white Republicans who tried to vote or run for office. In New Orleans, one of the most flagrant incidents of violence left 34 blacks and four whites dead, with scores of others wounded, when they attempted to hold a convention favoring black suffrage. Deeply disturbed by such developments and emboldened by substantial electoral victories in the fall of 1866, congressional Republicans approached the issue more aggressively in the winter of 1866-67. To more and more Republicans, many of whom were changing their views in the cauldron of circumstances, black enfranchisement began to appear essential to protect the freedmen, provide the Republican Party with an electoral base in the South, and make it possible for loyal governments to be elected in the once-rebellious states.

This surge of activity, fed by continued Southern intransigence, culminated in the passage of the Reconstruction Act of March 1867. The act, the legal centerpiece of Radical Reconstruction, denied recognition to the existing state governments of the South and authorized continued military rule of the region under the control of Congress. In order to terminate such rule and be fully readmitted to the Union, each southern state was required to ratify the Fourteenth Amendment and to approve, by manhood suffrage, a state constitution that permitted blacks to vote on the same terms as whites. President Johnson vetoed the bill, but his veto was quickly overridden. To rejoin the political nation, the states of the Confederacy were now compelled to permit blacks to vote.

Under the protective umbrella of the Reconstruction Act, politics in the South were transformed. In 1867 and 1868, African Americans, working with white Unionists and Republicans — most of whom came from poor or modest circumstances — elected new state governments, wrote progressive constitutions that included manhood suffrage provisions, and ratified the Fourteenth Amendment; black enthusiasm for political participation was so great that freedmen often put down their tools and ceased working when elections or conventions were being held. By June 1868, seven states, with manhood suffrage, had been readmitted to the Union, and the process was well under way elsewhere. All this was achieved despite fierce opposition from upper-class whites, who feared that a biracial alliance of blacks and nonelite whites would superintend the erection of a new and inhospitable economic and political order. The intensity of white hostility was manifested in a petition that conservatives in Alabama sent to Congress, denouncing the enfranchisement of “Negroes,”

in the main, ignorant generally, wholly unacquainted with the principles of free Governments, improvident, disinclined to work, credulous yet suspicious, dishonest, untruthful, incapable of self-restraint, and easily impelled . . . into folly and crime . . . how can it be otherwise than that they will bring, to the great injury of themselves as well as of us and our children, blight, crime, ruin and barbarism on this fair land? . . . do not, we implore you, abdicate your own rule over us, by transferring us to the blighting, brutalizing and unnatural dominion of an alien and inferior race.

Nor was southern opposition purely rhetorical: antiblack and anti-Republican violence flared up throughout the region, often spearheaded by the rapidly growing Ku Klux Klan.

The Fifteenth Amendment

By the late 1860s, most radical and moderate Republicans had concluded that the protection of African American interests in the South (as well as Republican party interests) also demanded the passage of a separate constitutional amendment banning racial discrimination at the polls.

After months of debate, Congress in the winter of 1869 passed the text of the Fifteenth Amendment, which declared that “no citizen” would be denied the right to vote because of “race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” The amendment was then sent to the states for ratification.

Although the moment was as propitious as it ever would be (Republicans controlled most state legislatures and President Grant actively supported the measure), opposition to the amendment was widespread and intense; it was passed easily only in New England, where blacks already voted, and in the South, where the federal government had already intervened to compel black enfranchisement. Elsewhere, battles over ratification were closely fought and heavily partisan. Democrats argued that the amendment violated states’ rights, debased democracy by enfranchising an “illiterate and inferior” people, and promised to spawn an unholy (and contradictory) mixture of intermarriage and race war. Republican legislators replied that black men had earned the franchise through their heroism as soldiers and that the amendment was needed to finally put the issue of black rights to rest; given the narrow boundaries of the amendment, they often avoided claiming suffrage as a universal right. What neither party mentioned much was that partisan interests were at stake, particularly in the border, Midwestern, and mid-Atlantic states, where the black population could boost the fortunes of the Republicans. In the end, most of these close contests were won by the Republicans, and the Fifteenth Amendment became part of the Constitution in February, 1870.

African Americans jubilantly celebrated the amendment’s ratification. Thousands of black voters, including military veterans with their wives and children, marched in triumphant parades throughout the country. Frederick Douglass, speaking in Albany in late April, declared that the amendment “means that we are placed upon an equal footing with all other men . . . that liberty is to be the right of all.”

The Fifteenth Amendment was certainly a landmark in the history of the right to vote. Spurred by pressure from blacks, deeply felt ideological convictions, partisan competition, and extraordinary conditions created by an internecine war, the federal government enfranchised more than a million men who only a decade earlier had been slaves. Moving with a speed reflecting rapidly shifting circumstances, Congress and state legislatures had created laws that would have been unthinkable in 1860 or even 1865. In the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments, the words right to vote were penned into the nation’s Constitution for the first time, announcing a new, active role for the federal government in defining democracy. Yet momentous as these achievements may have been, the limitations of the Fifteenth Amendment were, as Henry Adams pointed out, as significant as its contents: the celebrations of the black community would soon prove to be premature, and the unresolved tension between federal and state authorities would vibrate for another century.

The South Redeemed

Even before Reconstruction came to a quasi-formal end in 1877, black voting rights were under attack. Elections were hotly contested, and white Southerners, seeking to “redeem” the region from Republican rule, engaged in both legal and extralegal efforts to limit the political influence of freedmen. In the early 1870s, both in the South and in the border states, districts were gerrymandered (i.e., reshaped for partisan reasons), precincts reorganized, and polling places closed to hinder black political participation. Georgia, Tennessee, and Virginia reinstituted financial requirements for voting, while local officials often made it difficult for freedmen to pay their taxes so they could vote.

Far more dramatic was a wave of what historian Eric Foner has called “counterrevolutionary terror” that swept the South between 1868 and 1871. Acting as the military, or paramilitary, arm of the Democratic Party, organizations such as the Ku Klux Klan mounted violent campaigns against blacks who sought to vote or hold office, as well as their white Republican allies. In 1870 alone, hundreds of freedmen were killed, and many more badly hurt, by politicized vigilante violence. Although the Klan was never highly centralized and actions generally were initiated by local chapters, its presence was felt throughout the region. Whites of all classes (but not all whites) supported the Klan, its leadership often drawn from the more “respectable” elements of society; support was so widespread that Republican state governments, as well as local officials, commonly found it impossible to contain the violence or convict offenders in court.

The national government did not stand by idly. In May 1870, stretching the limits of its constitutional powers, Congress passed an Enforcement Act that made interference with voting a federal offense, punishable in federal courts — which presumably were more reliable than state courts. This first enforcement act was followed by others, including the Ku Klux Klan Act, which, among its provisions, authorized the president to deploy the army to protect the electoral process. However, by the mid-1870s, many northern Republicans, including President Grant, had lost their enthusiasm for policing the South; preoccupied with an economic depression and labor conflict in the North, they wearily drifted toward a “let alone policy.” In September 1875, one Republican newspaper referred to the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments as “dead letters.”

The Redeemers who were gaining power throughout the South in the 1870s had goals that were at once political, social, and economic. Most immediately they sought to drive the Republicans from power and elect Democrats, an objective hard to attain in a fully enfranchised South. Limiting black voting therefore was a means to a precise end; but it was more than that. Keeping freedmen from the polls was also a means of rebuffing broader claims to equality, a way of returning blacks to “their place,” of making clear that, whatever the Fourteenth Amendment said, blacks did not enjoy full citizenship.

There were important class dimensions to this political and racial agenda. Freedmen not only were men of a different race, they also constituted the primary labor supply of the agricultural South. Emancipation and Reconstruction threatened white control over needed black labor, and landowners and merchants sought both to halt the erosion of labor discipline and to utilize the state to enforce their dominance. It was no accident that the Klan targeted economically successful blacks or that it tried to keep freedmen from owning land. When Redeemer governments came to power, they commonly passed draconian vagrancy laws (subjecting anyone without a job to possible arrest) as well as legislation prohibiting workers from quitting their jobs before their contracts expired. The Redeemers also enacted laws that harshly punished petty theft, gave landlords complete control of crops grown by tenants, and reduced the proportion of tax revenues that went to education and social improvements. The resistance to black voting was rooted in class conflict as well as racial antagonism.

The pace of Redemption was quickened by the presidential election of 1876 and the subsequent removal of the last federal troops from the South. At roughly the same time, the Supreme Court (in U.S. v. Cruikshank and U.S. v. Reese) challenged key provisions of the enforcement acts. In 1878, moreover, Democrats won control of both houses of Congress for the first time in 20 years. The upshot of these events — which reflected the North’s growing fatigue with the issue of black rights — was to entrust the administration of voting laws in the South to state and local governments. Between 1878 and 1890, the average number of federal prosecutions launched annually under the enforcement acts fell below 100; in 1873 alone there had been more than 1,000.

In the Deep South, the Republican Party crumbled under the onslaught of Redemption, but elsewhere the party hung on, and large, if declining, numbers of blacks continued to exercise the franchise. Periodically they were able to form alliances with poor and upcountry whites and even with some newly emerging industrial interests sympathetic to the pro-business policies of the Republicans. Opposition to the conservative, planter-dominated Redeemer Democrats, therefore, did not disappear: elections were contested by Republicans, by factions within the Democratic Party, and eventually by the Farmers’ Alliance and the Populists. Consequently, the Redeemers, who controlled most state legislatures, continued to try to shrink the black (and opposition white) electorate, resorting when necessary to violence and fraudulent vote counts. In 1883, a black man in Georgia testified to a Senate committee that “we are in a majority here, but you may vote till eyes drop out or your tongue drops out, and you can’t count your colored man in out of them boxes; there’s a hole gets in the bottom of the boxes some way and lets out our votes.”

In 1890, in response to the increasingly widespread discrimination against black voters in the South, liberal Republican members of Congress pressed for passage of the Federal Elections Bill, which came to be called the “Lodge Force Bill.” The bill called for renewed activity by the federal government to enforce the Fifteenth Amendment in the South. It was narrowly defeated in Congress.

The year 1890 also marked the beginning of systematic efforts by Southern states to disfranchise black voters legally. Faced with recurrent electoral challenges, the annoying expense of buying votes, and controversy surrounding epidemics of fraud and violence, Democrats chose to solidify their hold on the South by modifying the voting laws in ways that would exclude African Americans without overtly violating the Fifteenth Amendment. In short order, Southern states adopted — in varying combinations — poll taxes, cumulative poll taxes (demanding that past as well as current taxes be paid), literacy tests, secret ballots (which functioned as de facto literacy tests), lengthy residence requirements, elaborate registration systems, confusing multiple voting-box arrangements, and eventually, Democratic primaries restricted to white voters. Criminal exclusion laws also were altered to disfranchise men convicted of minor offenses, such as vagrancy and bigamy. The overarching aim of such restrictions, usually undisguised, was to keep poor and illiterate blacks — and in Texas, Mexican Americans — from the polls. “The great underlying principle of this Convention movement . . . was the elimination of the negro from the politics of this State,” emphasized a delegate to Virginia’s constitutional convention of 1901-2. Literacy tests served that goal well, since 50 percent of all black men (as well as 15 percent of all whites) were illiterate; and even small tax requirements were a deterrent to the poor. Notably, it was during this period that the meaning of poll tax shifted; where it once had referred to a head tax that every man had to pay and that sometimes could be used to satisfy a taxpaying requirement for voting, it came to be understood as a tax that one had to pay in order to vote.

Small errors in registration procedures or marking ballots might or might not be ignored at the whim of election officials; taxes might be paid easily or only with difficulty; tax receipts might or might not be issued. Discrimination was built into literacy tests, with their “understanding” clauses: officials administering the test could, and did, judge whether a prospective voter’s “understanding” was adequate. Discrimination, as well as circumvention of the Fifteenth Amendment, was also the aim of the well-known grandfather clauses that exempted men from literacy, tax, residency, or property requirements if they had performed military service or if their ancestors had voted in the 1860s. The first Southern grandfather clause was adopted in South Carolina in 1890; with exquisite regional irony, it was modeled on an anti-immigrant Massachusetts law of 1857.

Such laws were not passed without controversy. Contrary to twentieth-century images of a monolithic solid South, there was substantial white opposition to new restrictions on the franchise: many upcountry whites, small farmers, Populists, and Republicans viewed such laws as a means of suppressing dissent, a self-interested and partisan grab for power by dominant, elite, often black-belt Democrats. Egalitarian voices were raised, insisting that it was “wrong” or “unlawful” to deprive “even one of the humblest of our citizens of his right to vote.” Commonly, apprehensions were voiced about the laws’ potential to disfranchise whites. A delegate from a predominantly white county in Texas asked whether a proposed poll tax had a “covert design,” since “it afflicts the poor man and the poor man alone.” Proponents of suffrage restriction, however, drowned such objections in rhetoric stressing the urgency of black disfranchisement while assuring whites that their political rights would not be subverted. “I told the people of my county before they sent me here,” declared R.L. Gordon at Virginia’s constitutional convention in 1901, “that I intended . . . to disfranchise every Negro that I could disfranchise under the Constitution of the United States, and as few white people as possible.”

Despite such claims, many advocates of so-called electoral reform were quite comfortable with the prospect of shunting poor whites aside along with African Americans. One little-noticed irony induced by the Fifteenth Amendment was that it led southern Democrats to resurrect class, rather than racial, obstacles to voting, a resurrection that was altogether compatible with the conservative views and interests of many of the landed, patrician whites who were the prime movers of disfranchisement. “I believe in the virtue of a property qualification,” proclaimed Gordon of Virginia. A New Orleans newspaper attacked manhood suffrage as “unwise, unreasonable, and illogical,” and Louisiana’s disfranchising laws targeted not only blacks but a political machine supported by working-class whites, many of them Italian. One Alabama disfranchiser publicly avowed his desire to eliminate “ignorant, incompetent, and vicious” white men from the electorate, while a Virginia delegate revived the notion of virtual representation in an attempt to mitigate the significance of legislation that would keep many whites from the polls.

Indeed, the late-nineteenth-century effort to transform the South’s electorate was grounded solidly in class concerns as well as racial antagonism. Not only was the disfranchisement of poor whites palatable to many of their better-off brethren, but the exclusion of black voters also had significant class dimensions. Ridding the electorate of blacks was a means of rendering most of the agricultural laborers of the rural South politically powerless, of restoring the “peasantry” to its pre-Civil War political condition. Taking this step would permit post-slavery agriculture to be organized and economic development to be promoted while landowners and businessmen wielded unchallenged control of the state.

To be sure, the upper classes were not alone in advocating black disfranchisement: the movement was actively supported by many poor and lower-middle-class whites, just as the Know-Nothing effort to disfranchise immigrants was backed by some native-born workers. Yet the presence of a racial and political schism within the lower classes did not blunt (though it did complicate and disguise) disfranchisement’s class edge. In the black-belt, cotton-growing counties that remained at the core of the South’s economy, a large majority of the laboring population was vulnerable to the new laws; in the region as a whole, the threat of a troublesome electoral alliance between blacks and poor whites could be eliminated. As historians have long noted, the political order of the new South was structured by class as well as racial dominance. In the words of an Alabama trade unionist, “the lawmakers . . . made the people believe that [the disfranchising law] was placed there to disfranchise the negro, but it was placed there to disfranchise the workingman.

The laws, of course, worked. In Mississippi after 1890, less than 9,000 out of 147,000 voting-age blacks were registered to vote; in Louisiana, where more than 130,000 blacks had been registered to vote in 1896, the figure dropped to an astonishing 1,342 by 1904. Throughout the region the black electorate was decimated, and many poor whites (as well as Mexican Americans) went with them. Just how many persons were barred from the polls is impossible to determine, but what is known is that both registration and turnout (calculated as the percentage of votes cast divided by number of men of voting age) dropped precipitously after the electoral laws were reconfigured. By 1910, in Georgia, only four percent of all black males were registered to vote. In Mississippi, electoral turnout had exceeded 70 percent in the 1870s and approached 50 percent in the decade after the Redeemers came to power: by the early twentieth century, it had plummeted to 15 percent and remained at that level for decades. In the South as a whole, post-Reconstruction turnout levels of 60 to 85 percent fell to 50 percent for whites and single digits for blacks. The enlargement of the suffrage that was one of the signal achievements of Reconstruction had been reversed, and the rollback had restored the Southern electorate to — at best — pre-Civil War proportions.

What this meant for the history of the twentieth-century South is well-known: the African- American population remained largely disfranchised until the 1960s, electoral participation remained low, and one-party rule by conservative Democrats became the norm. Viewed through a wider lens, these developments also signified that in a major region of the United States the nineteenth-century trend toward democratization had been not only checked, but reversed: the increasingly egalitarian institutions and convictions forged before the Civil War were undermined, while class barriers to electoral participation were strengthened or resurrected. The legal reforms of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries created not just a single-party region but a class-segmented as well as racially exclusive polity. Large segments of the rural, agricultural working class — America’s peasantry — were again voteless, and industrialization, which became increasingly important to the region after 1880, took place in a profoundly undemocratic society.

Women’s Suffrage

The history of voting rights for women carved its own path through the political landscape. As half the population, women constituted the largest group of adults excluded from the franchise at the nation’s birth and for much of the nineteenth century. Their efforts to gain the right to vote persisted for more than 70 years, eventually giving rise to the nation’s largest mass movement for suffrage, as well as a singular countermovement of citizens opposed to their own enfranchisement. Women enjoyed (or at least possessed) different, more intimate relationships with the men who could enfranchise them than did other excluded groups, such as African Americans, aliens, or the propertyless. Moreover, the debates sparked by the prospect of enfranchising women had unusual features — with fairly conventional propositions about political rights and capacities contending with deeply felt and publicly voiced fears that female participation in electoral politics would undermine family life and sully women themselves.

Yet distinctive as this history may have been, it always ran alongside and frequently intersected with other currents in the chronicle of suffrage. The broad antebellum impulse toward democratization helped to fuel the movement for women’s rights; decades later, the reaction against universal suffrage retarded its progress. Black suffrage and women’s suffrage were closely linked issues everywhere in the 1860s and in the South well into the twentieth century; similarly, the voting rights of immigrants and the poor pressed repeatedly against the claims of women in the North and West. To some degree, this interlacing was inherent and structural. Women, after all, were not a socially segregated group; they were black and white, rich and poor, foreign-born and native.

A formal and energetic movement to enfranchise women began to take root in the United States in the late 1840s. It gained strength during the following decade, but then, understandably enough, paused for much of the Civil War.

As the war ended and Reconstruction began, leaders of the suffrage movement, including Elizabeth Cady Stanton and her indefatigable collaborator, Susan B. Anthony, were optimistic about its prospects. The public embrace of democracy was as broad as it ever had been; the war and the plight of the freedmen had energized the language of universal rights; and the Republican Party, home of the staunchest advocates of civil and political rights, was firmly in power. What the suffragists anticipated was a rising tide of prodemocratic sentiment that would lift women, as well as African Americans, into the polity. We intend, declared Stanton, “to avail ourselves of the strong arm and the blue uniform of the black soldier to walk in by his side.” Suffragists also felt that their claim to the franchise had been strengthened by the energetic support women had lent to the war effort: such activities presumably had neutralized the oft-repeated argument that women should not vote because they did not bear arms.

Yet the suffragists were doomed — or at least slated — to be disappointed. Within a few months of the war’s end, Republican leaders and male abolitionists began to signal their lack of enthusiasm for coupling women’s rights to black rights. “One question at a time,” intoned Wendell Phillips. “This hour belongs to the negro.” The Fourteenth Amendment disheartened suffragists: while offering strong, if indirect, federal support to black enfranchisement, the amendment undercut the claims of women by adding the word male to its pathbreaking guarantee of political rights. Although well aware of the strategic concerns that prompted such language, Stanton, in a prescient warning, declared that “if that word ‘male’ be inserted, it will take us a century at least to get it out.”

After the passage of the Fifteenth Amendment, which decisively severed the causes of black (male) and women’s suffrage, the leaders of the suffrage movement settled down to a prolonged effort to gain the right to vote for women. They had a few successes in western states in the late nineteenth century, and a number of other states permitted women to vote in school board or local elections. But progress was slow until the second decade of the twentieth century. And it was particularly slow in the South.

There were, of course, active suffragists in the region, both white and black; there also were male politicians, usually Republican, who embraced the cause in constitutional conventions and state legislatures. Still, the movement was slow to gather steam: suffrage organizations were far smaller and less visible than in the North, no referenda were held, and even school-district suffrage remained a rarity. This lag had two critical sources. The first was the South’s predominantly rural, agricultural social structure. The social strata most receptive to woman suffrage — urban, professional, educated, middle-class-emerged belatedly and slowly in the South. Most women continued to live in an entirely agricultural world, while elite women from plantation and textile-manufacturing families often joined a vocal antisuffragist countermovement.

The second reason that the movement lagged was race. Although suffrage advocates argued that their enfranchisement would solidify white supremacy — because white women outnumbered black men and women — this claim made little headway with white male Southerners: to them, women’s suffrage meant opening the door to a large new constituency of black voters, something to be avoided at all costs. As Senator Joseph E. Brown of Georgia put it in 1887, little could “be said in favor of adding to the voting population all the females of that race.” In addition, the movement for a national suffrage amendment was repellent to southern Democrats, who perceived such an amendment as yet another federal threat to states’ rights.

A new surge of organizing began in 1910, however, rooted in an urban and quasi-urban middle class that had grown rapidly in preceding decades: that middle class spawned Southern New Women who were educated, had held professional or white-collar service jobs, and were married to (or the children of) professionals and small businessmen. This new generation of white Southern suffragists — women such as Gertrude Weil from the railroad juncture town of Goldsboro, North Carolina, or Margaret Caldwell of Nashville, the daughter of a doctor and wife of a car dealer — was motivated by concerns very similar to those of their northern counterparts, and they joined hands with National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) and other national organizations, reviving or building chapters throughout the South. By 1913, every southern state had a suffrage organization allied with NAWSA; within a few years, Virginia’s organization had 13,000 members and Alabama possessed 81 local suffrage clubs. These women were joined (although usually not in the same organizations) by numerous African-American women who believed with good reason that they, more than anyone perhaps, had a compelling need to be enfranchised. Notably, some Southern suffragists, like their Northern colleagues, made concerted efforts to reach out to the South’s emerging labor movement and to link the cause of suffrage to the exploitation of working people. “We have no right,” declared Virginia’s Lucy Randolph Mason, “to stand idly by and profit by the underpaid and overdriven labor of people bound with the chains of economic bondage.”

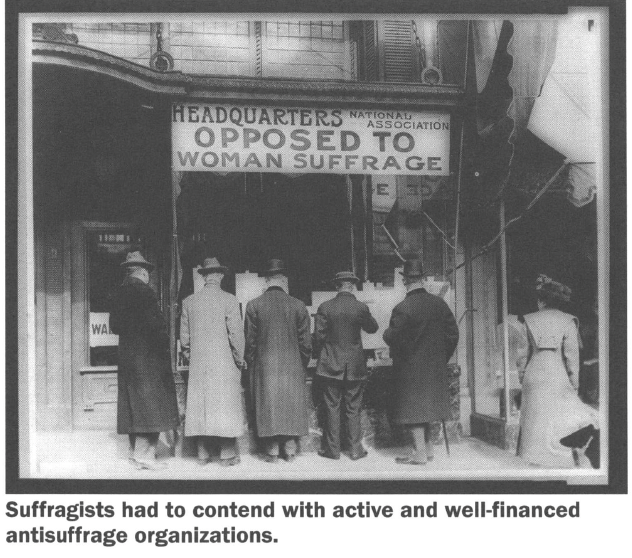

Despite such efforts, the soil for democratic expansion remained less fertile in the South. Not only was the middle class relatively small and the rural world large and difficult to reach, but antisuffrage forces were strong and well organized. In addition to the liquor interests and political machines, such as those in New Orleans and parts of Texas, suffragists had to contend with active and well-financed antisuffrage organizations, led by upper-class women and men tied both to the world of plantation agriculture and to the new industrial South of textiles and railroads. This elite opposition was grounded in southern variants of traditional gender ideology and in a fierce class-based antagonism to the types of social reform (including labor reform) that many suffragists advocated.

The opposition also had a great deal to do with race. By the latter years of the Progressive era, African Americans had been successfully disfranchised throughout the South, and most whites were intent on keeping it that way. Politicians were loath to tinker at all with electoral laws, and they feared that black women might prove to be more difficult to keep from the polls than black men — because black women were believed to be more literate than men and more aggressive about asserting their rights, and also because women would be unseemly targets of repressive violence. “We are not afraid to maul a black man over the head if he dares to vote, but we can’t treat women, even black women, that way,” fretted a senator from Mississippi. Although some white suffragists continued to advance the statistical argument that woman suffrage would insure white supremacy, that rhetorical claim made no more headway after 1910 than it had in the 1890s.

Compounding the difficulties faced by southern suffragists was another issue, the growing support nationally for a federal amendment. If women’s suffrage itself was unpopular in much of the South, a federal constitutional amendment was anathema. Not implausibly, many Southerners were convinced that a federal amendment would open the doors to Washington’s intervention in elections, to enforcement — so glaringly absent — of the Fifteenth Amendment and any subsequent amendment that might appear to guarantee the voting rights of black women. In addition to strengthening antisuffragism, this issue split the southern suffrage movement itself, often along lines coinciding with suffragists’ attitudes toward racial equality. While some suffragists welcomed the prospect of a federal strategy (either on principle or because it was more likely to succeed than state efforts), others — most vocally, Kate Gordon of Louisiana — denounced the possibility. Gordon, a champion of women’s suffrage as a bulwark against black political power, resigned her leadership position in NAWSA to protest the organization’s renewed efforts to promote a federal amendment. In 1913, she founded the Southern States Woman Suffrage Conference to focus on passage of state laws and convincing the national Democratic Party to endorse suffrage on a state-by-state basis. Gordon’s new organization — which she thought should replace NAWSA’s in the South — proved to be short-lived, but by 1915 it was evident that the two currents in the Southern movement coexisted very uneasily with one another.

Thanks in part to the unusual political circumstances of World War I, a constitutional amendment calling for women’s suffrage was passed by the House of Representatives in 1918 and by the Senate the following year. It was then sent to the states for ratification. Although many northern states had already enfranchised women and clearly supported the Nineteenth Amendment, its ratification by the necessary three-quarters of all states was by no means assured.

To no one’s surprise, the South remained recalcitrant. In the hope of wooing Southern votes, some politicians, such as Jeannette Rankin (the first woman elected to the House of Representatives), as well as activists such as Carrie Chapman Catt and Alice Paul, tried to reassure Southerners that the amendment did not threaten white supremacy (it meant “the removal of the sex restriction, nothing more, nothing less”); and NAWSA opportunistically distanced itself from black suffragists. But despite their rather unprincipled efforts, the South remained opposed, with the full-throated cry of states’ rights giving tortured voice to the region’s deep anxieties about race. Nowhere were those anxieties more vividly manifested than in Louisiana and Mississippi, where Kate Gordon and her followers actively and successfully worked to defeat the amendment; in the end, it was approved only by the four border states of Kentucky, Tennessee, Texas, and Arkansas. Nonetheless, women everywhere, including Kate Gordon, were enfranchised. On August 18, 1920, Tennessee, by a margin of one vote, became the 36th state to vote positively on the amendment; a week later, after ratification had been formally certified, the Nineteenth Amendment was law.

Race and the Second Reconstruction

The South was a cauldron of racial tension in the 1950s. Throughout the region — and particularly in its many small and medium-sized cities — African Americans pressed forward against the boundaries of America’s caste system, demanding an end to social segregation and second-class citizenship. Sometimes led by national and regional organizations, such as the NAACP, trade unions, or the newly formed Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and sometimes acting entirely on local initiative, black citizens marched, rallied, boycotted buses, wrote petitions, and filed lawsuits to challenge the Jim Crow laws that had kept them in their place for more than half a century. Encouraged by the Supreme Court’s 1954 decision, in Brown v. Board of Education, that separate was not equal, the black community focused particular attention on the integration of schools and institutions of higher learning. African Americans also kept the spotlight on the right to vote, which was always at the heart of the civil rights movement. Convinced that the franchise was an important right in itself and the key to securing other civil rights, hundreds of thousands of African Americans, acting along and in organized registration drives, attempted to enter their names on registry lists and participate in elections. “Once Negroes start voting in large numbers,” observed one black newspaper, “the Jim Crow laws will be endangered.” “Give us the ballot and we will fill our legislative halls with men of good will,” declared the Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr., to a crowd of nearly 30,000 people in front of the Lincoln Memorial in 1957.

The push for civil rights encountered formidable opposition, which evolved into a semiformal policy of “massive resistance” after the Brown decision. To be sure, an increasing number of white Southerners were recognizing the inevitability, and even desirability, of integration; many advocates of a modernized New South sought to remove the stigma attached to the region’s racial practices, while the mechanization of agriculture diminished the reliance on semi-captive black labor. Nonetheless, resistance to equal rights remained fierce and sometimes violent. Mayors and governors refused to integrate schools and public facilities; legislatures declared that they would not dismantle Jim Crow; sheriffs arrested and beat black protesters and their white allies. Meanwhile, the fortunes of liberal or populist white politicians who displayed any sympathy with blacks, such as Earl Long in Louisiana and Jim Folsom in Alabama, were spiraling into decline.

The widespread resistance to integration only underscored the black community’s need for political rights, but throughout the 1950s their efforts to vote were thwarted more often than not. In seven states (Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Virginia), literacy tests kept African Americans from the polls: failure of the test could result simply from misspelling or mispronouncing a word. In 1954, Mississippi instituted a new, even more difficult “understanding test,” complete with a grandfather clause exempting those already registered. In Alabama, prospective registrants had to be accompanied by white citizens who would “vouch” for them. In Louisiana, members of the White Citizens Council purged black registrants from the voting lists for minor paperwork irregularities, and a 1960 law provided for the disfranchisement of a person of “bad character” — which included anyone convicted of refusing to leave a movie theater or participating in a sit-in.

Registrars in many towns and cities thwarted black aspirants by not showing up at the office or by simply refusing to register blacks when they did. Those who were adamant about registering could lose their jobs, have loans called due, or face physical harm. More than a few were killed.

It was apparent to nearly all black leaders that the civil rights movement could succeed only with significant backing from the federal government: the black community by itself could not compel city and state authorities to cease discriminating. But Washington, although sympathetic, was hesitant. Liberal Democrats in Congress were eager to take action, but their influence was offset by the power of southern Democrats. Republicans were similarly torn: while the desire to court black voters reinforced the party’s traditional pro-civil rights principles, many Republicans also hoped to make inroads into the solid South by winning over white Southern voters.

The pace of governmental activity began to quicken in 1960, largely because the political temperature was soaring in the South. A sit-in at a segregated luncheon counter in Greensboro, North Carolina, sparked a wave of civil disobedience by young African Americans who refused to adhere to the strictures of Jim Crow; freedom riders rode buses to try to integrate interstate transportation; in Birmingham and other cities, mass movements challenged segregation and disfranchisement; efforts to register black voters even reached into the Deep South bastions of white supremacy in rural Alabama and Mississippi (see “Freedom Is a Constant Struggle”).

The growing militance of the black freedom movement only stiffened the opposition. The governors of Alabama and Mississippi refused to desegregate their universities; voting districts were gerrymandered to dilute the influence of blacks who did manage to register; freedom riders were beaten and their buses burned; police arrested protestors by the thousands; bombs were tossed into black churches; and activists were occasionally — as in Mississippi in 1964 — murdered in cold blood. In 1961, the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights (CCR) reported that “in some 100 counties in eight Southern states,” discriminatory laws, arbitrary registration rulings, and threats of “physical violence or economic reprisal” still kept most “Negro citizens . . . from exercising the right to vote.”

The commission also concluded that the federal government’s reliance on county-by-county litigation was too “time consuming, expensive, and difficult” to bring an end to discriminatory voting practices. “Broader measures are required,” the CCR intoned, urging Congress once again to pass legislation “providing that all citizens of the United States shall have a right to vote in Federal or State elections” if they could meet reasonable age and residency requirements and had not been convicted of a felony.

Neither Congress nor President John Kennedy was ready to bite that bullet. Although Kennedy’s narrow electoral victory owed a great deal to black voters, he lacked a strong popular mandate, had limited influence with Congress, and did not regard civil rights as a high-priority issue. His approach, accordingly, was nearly as cautious as Eisenhower’s, involving the support of voter registration campaigns, a constitutional amendment to ban poll taxes, and lawsuits to enforce the Civil Rights Act. These efforts bore some fruit. Rulings by federal judges stripped away more of the legal camouflage that was sheltering discrimination; the Twenty-fourth Amendment (banning poll taxes) was ratified with relatively little opposition; and black registration in the South rose to more than 40 percent by 1964. Still, the pace of legal progress was outstripped by the acceleration of conflict in the South. Consequently, the administration in 1963 drafted an omnibus civil rights bill designed to give strong federal support to equal rights, although it said little about voting rights per se.

Kennedy did not live to witness the passage of his civil rights bill, but Johnson successfully seized the moment after Kennedy’s assassination to urge the bill’s passage as a tribute to the late president. As important, Johnson himself was elected to the presidency in 1964 with an enormous popular vote, offering the first Southern president in a century the opportunity to complete the Second Reconstruction. Personally sympathetic to the cause of black suffrage, bidding for a place in history, and prodded by the nationally televised spectacle of police beatings and arrests of peaceful, prosuffrage marchers in Selma, Alabama, Johnson went to Congress in March 1965 to urge passage of a national Voting Rights Act. “The outraged conscience of a nation” demanded action, he told a joint session of Congress. “It is wrong — deadly wrong — to deny any of your fellow Americans the right to vote,” he reminded his former colleagues from the South. Then, rhetorically identifying himself with the civil rights movement, he insisted that “it is really all of us, who must overcome the crippling legacy of bigotry and injustice. And we shall overcome.”

Johnson’s words, spoken to a television audience of 70 million and to a somber, hushed Congress that interrupted him 40 times with applause, were sincere, principled, and moving. Yet, astute politician that he was, the president also knew that the Democrats’ political balancing act was over: with the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the party had decisively tilted away from the white South and toward black voters, and now it was going to need as many black voters as possible to have a chance of winning Southern states. Johnson understood that the politics of suffrage reform once again had entered its endgame: black enfranchisement would become a reality, and few politicians in either party wished to antagonize a new bloc of voters by opposing their enfranchisement.

The Voting Rights Act

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 contained key elements demanded by civil rights activists and the Commission on Civil Rights. Designed as a temporary, quasi-emergency measure, the act possessed an automatic “trigger” that immediately suspended literacy tests and other “devices” (including so-called good character requirements and the need for prospective registrants to have someone vouch for them) in states and counties where fewer than 50 percent of all adults had gone to the polls in 1964; the suspensions would remain in force for five years. In addition, the act authorized the attorney general to send federal examiners into the South to enroll voters and observe registration practices. To prevent the implementation of new discriminatory laws, the act prohibited the governments of all affected areas from changing their electoral procedures without the approval (or “pre-clearance”) of the civil rights division of the Justice Department. States could bring an end to federal supervision only by demonstrating to a federal court in Washington that they had not utilized any discriminatory devices for a period of five years. Finally, the act contained a congressional “finding” that poll taxes in state elections abridged the right to vote, and it instructed the Justice Department to initiate litigation to test their constitutionality.

The Voting Rights Act was passed by an overwhelming majority, as moderate Republicans joined with Democrats to carry out what Johnson called the “tumbling” of “the last of the legal barriers” to voting. Some conservative Republicans and southern Democrats voted negatively, but recognizing the inevitability of the bill’s triumph and the political wisdom of supporting it, 40 Southern congressmen voted favorably. Hailed by one activists as “a milestone” equal in importance to the Emancipation Proclamation, the legislation had an immediate impact, particularly in the Deep South. Within a few months of the bill’s passage, the Justice Department dispatched examiners to more than 30 counties in four states; scores of thousands of blacks were registered by the examiners, while many more were enrolled by local registrars who accepted the law’s dictates to avoid federal oversight. In Mississippi, black registration went from less than 10 percent in 1964 to almost 60 percent in 1968; in Alabama, the figure rose from 24 percent to 57 percent. In the region as a whole, roughly a million new voters were registered within a few years after the bill became law, bringing African-American registration to a record 62 percent.

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 was indeed a milestone in American political history. A curious milestone, to be sure, since the essence of the act was simply an effort to enforce the Fifteenth Amendment, which had been law for almost a century. But the very fact that it had taken so long for a measure of this type to be adopted was a sign of its importance. Racial barriers to political participation had been a fundamental feature of American life, and resistance to racial equality was deeply ingrained; so too was resistance to federal intervention into the prerogatives of the states. That such resistance was finally overcome in the 1960s was a result of the convergence of a wide array of social and political forces: the changing socioeconomic structure of the South, the migration of blacks to southern cities, the growing electoral strength of African-American migrants in the North, the energies of the civil rights movement, the vanguard role played by black veterans of World War II, and a renewed American commitment to democracy occasioned by international struggles against fascism and communism. As is often the case, more contingent factors played a role as well — including the post-assassination election of a skillful Southern president, the talents of civil rights leaders such as Martin Luther King, Jr., and technological changes in media coverage that brought the violence and ugliness of a “Southern” problem in to the homes of citizens throughout the nation.

The Voting Rights Act did not suddenly put an end to racial discrimination in Southern politics. (For reasons of brevity, the role of the Supreme Court — which was large — is not discussed in these pages. In a stunning series of decisions, the Court not only upheld the Voting Rights Act but substantially broadened the federal judiciary’s protection of the right to vote — in part by bringing many areas of voting law under the umbrella of the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.) To a considerable degree, the locus of conflict shifted from the right to vote to the value of the vote, but reports from the field made clear, to the Justice Department and the CCR, that racial obstacles to enfranchisement per se also persisted long after 1965. As a result, the act was renewed three times after its initial passage, despite a political climate that grew more conservative with each passing decade. In 1970, despite significant reluctance in the Nixon administration and congressional jockeying to weaken the measure, the bill was renewed for five years, while the ban on literacy tests was extended to all states. In 1975, the act was extended for an additional seven years, and its reach enlarged to cover “language minorities,” including Hispanics, Native Americans, Alaskan Natives, and Asian Americans; the “language minority” formulation was, in effect, a means of redefining race to include other groups who had been victims of discrimination. In 1982, despite the Reagan administration’s anti-civil rights posture, the act’s core provisions were extended for an additional 25 years. Throughout this period, the Justice Department, as well as the Civil Rights Commission, worked actively to promote black enfranchisement and reviewed thousands of proposed changes in electoral law.

The debates surrounding these renewals — and they were substantial — were grounded in a new partisan configuration that in part was a consequence of the Voting Rights Act itself. By the late 1960s, all Southern states contained a large bloc of black voters whose loyalty to the Democratic Party had been cemented by the events of the Kennedy and Johnson years; since these voters constituted a core Democratic constituency, Democratic politicians, even within the South, generally supported efforts to shore up black political rights. At the same time, conservative white Southerners, joined by some migrants into the region, flocked to the Republican Party, reviving its fortunes in the South and becoming a critical conservative force in the national party. Efforts to weaken the Voting Rights Act, or even to let it expire, invariably came from these Southern Republicans and from national Republican leaders — such as Nixon and Reagan — who wanted and needed their support. The party of Lincoln, as one critic quipped, had donned a “Confederate uniform.” That almost all of these Republican efforts failed — despite the conservative drift of the 1970s and 1980s — was a clear sign that the nation had turned a corner, that formal racial barriers to enfranchisement were dead. In 1982, even South Carolina Republican Senator Strom Thurmond, who had led the Dixiecrat exodus from the Democratic Party in 1948, voted in favor of extending the Voting Rights Act, marking the first time in his astonishingly long career that he had supported passage of a civil rights bill.

Tags

Alexander Keyssar

Alexander Keyssar, formerly of Duke University, is Stirling Professor of History and Social Policy at the John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University. (2003)