The More Things Change, The More They Stay the Same

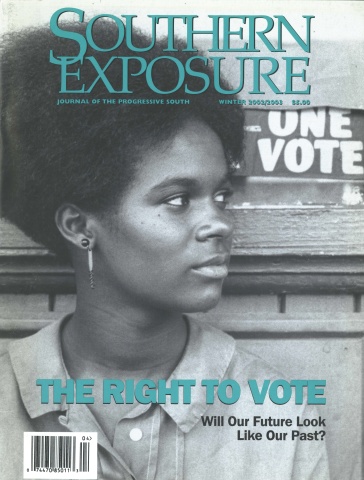

This article first appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 30 No. 4, "The Right to Vote." Find more from that issue here.

Tennessee is one of the jewels of the New South, glittering with new construction in its cities and suburbs, a growing population, and, of course, relentless urban sprawl and hideous traffic jams. Yet, like all the South, it remains a place haunted by its past. This was evident in the 2000 elections, when allegations of racist voting irregularities swept through the South, and particularly this state. Black voters were reportedly told to get behind the white voters in Murfreesboro and Memphis (“You know what it is to stand at the back of the bus,” a Murfreesboro election worker allegedly said). In the Hadley Park district of Nashville, black voters were told to remove NAACP stickers from their cars — or leave the polling place without voting. Police standing around polling places intimidated African-American voters in several locations. In western Tennessee and the Upper Antioch and Hadley Park areas of Nashville, black voters stood in lines over a mile long to use ancient punch-card machines on the verge of falling apart.

The Department of Safety mysteriously lost and mishandled voter records and applications all over the state, turning the so-called “motor voter” process into a nightmare. Tennessee State University, a historically African-American school, was the only college in Central or Eastern Tennessee that didn’t get satellite polling place status. Polling places were moved and changed their hours of operation all over western and southern Tennessee without notifying anybody.

Tennessee’s felon purge list was possibly as problem-ridden as Florida’s. Only the quick work of Dr. Blondell Strong, a Nashville NAACP representative, kept many former inmates from being improperly barred from voting in Nashville. In some areas, such as Memphis and Bolivar, simple misdemeanors placed some people on the purge list. Clifton Polk, an NAACP worker in Bolivar, filed a complaint with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission over the difficulties experienced in his area.

The Tennessee Voter Empowerment Team met at the Tennessee NAACP Conference of Branches on November 17, 2000, and released their findings to the state. There was massive evidence that thousands — perhaps even tens of thousands — had been disenfranchised, mostly African Americans. The evidence was serious enough to merit a current lawsuit conducted by the U.S. Department of Justice.

But the vast majority of media coverage that appeared on this issue came from the black press, newspapers like the Tennessee Tribune, Nashville Pride, and Urban Flavor. For several months, major news outlets such as The Tennessean (a Gannett paper), The Scene, and local network affiliates essentially ignored the entire. Drew Smith, a producer for NewsChannel 5 (Nashville’s CBS affiliate), Drew Smith, received reports on election night of police intimidation and African Americans turned away from polling places in Memphis. Smith, along with the news director and the anchor, refused to run the story, either that night or in the future. (The employee who passed this story on to me begged to remain anonymous, terrified of losing his job.)

“People want to sweep this under the rug,” says Rev. Neal Darby, head of the Greater Nashville Black Chamber of Commerce. “They don’t want to think it could have happened here.” But Tennessee, in some ways, has the dubious distinction of representing the worst of the worst in United States voting. And now, with the 2002 elections looming, we are once again faced with the same question as in 2000: will we ever have justice in voting here?

Voting irregularities were reported in 23 states in 2000. Yet Tennessee may have the most strikes against it going into the 2002 election cycle, far more than Florida, the state that received the lion’s share of the coverage. Being one of only three states sued by the Department of Justice is only the beginning. The governor of Tennessee, Don Sundquist, never signed notable election reform legislation. The flawed felon purge list was not corrected. The oldest type of voting machine has not been replaced. Tennessee is one of only six states that received a grade of F in the NAACP’s report on the voting situation nationwide.

This is not a new story, and it isn’t necessary to go back to the pre-civil rights era to find significant problems. In 1992, hundreds of people in Davidson County showed up to vote and were told they were at the wrong precincts. In 1994, election results from early voting weren’t counted until the Friday after Election Day. In 1997, faulty computer equipment at early voting sites in Nashville kept untold hundreds from voting. In 1998, sample ballots were not published before early voting, as required by state law.

Problems continued in the 2002 primaries. Twenty-one of the state’s 95 counties were still using the infamous punch-card ballots, exactly the type that caused problems in Florida. Michael McDonald, Davidson County’s Administrator of Elections, acknowledges that polling places were understaffed and the workers badly trained. Redistricting caused polling places to be changed throughout the state, and frequently voters were not informed. Though the state is required by law to send registration cards to voters, 20,000 Davidson County voters received their cards late, and some never received them at all. Up to 500 voters in Madison, Hadley Park, Brick Church Pike, and Bordeaux (the poorest areas, which had the most problems in 2000) received incorrect polling information on their cards. Phone lines that were supposed to keep voters informed on primary day were overwhelmed and out of order.

Voters in almost two dozen Davidson county precincts who asked for paper tally sheets for write-in votes had their ballots mysteriously go missing. The Tennessean — whose coverage of these issues has significantly improved since 2000 — went to the Election Commission warehouse and hand-counted all the tally sheets to confirm this fact. The ballots have never been found.

On Friday, Nov. 1, three days before the general election, Tennessee’s state election coordinator, Brook Thompson, warned that Republicans had encouraged poll watchers to challenge voters who had registered under Tennessee’s “motor voter” law. Thompson presented as evidence an internal GOP email obtained by Justice Department lawyers.

“In light of the apparent suspicion and possible hostility that some poll watchers may have to (motor voter) voters,” Thompson wrote in a memo to county election officials, “we must advise the election officials that the poll watchers cannot and will not be allowed to harass and/or intimidate voters. We will not be patient with any person seeking to create a hostile and unfriendly atmosphere in the polling place.”

In a particularly surreal note, state Republicans criticized the federal government’s involvement in the matter: “With all due respect, I don’t think the Justice Department [headed by John Ashcroft] knows what it’s doing,” said John Ryder, the party’s attorney in Tennessee.

“There is obviously room for improvements, and we’re going to make those improvements,” says McDonald. However, there is still no state law requiring a recount in close elections or setting uniform standards for recounts. Almost two dozen election bills proposed in the Tennessee legislature soon after the 2000 election went nowhere, including proposals to allow provisional voting, adopt minimum standards for nonpartisan voter education, and provide central voting locations for voters who have gone to incorrect polling places. One bill detailing what counts as a vote in counties that still use punch-card ballots did go through, but it’s largely a moot point, since recounts are not required.

Republican Senator Fred Thompson explains that the state simply doesn’t have the money to address all these problems due to seemingly perennial budget crunches, although he says that “we have taken some steps to rectify some problems.” There isn’t any money left in the loan fund that counties could previously borrow from to replace outdated voting machines; it was cleaned out by the legislature while balancing the budget this year. “The NAACP wants more money spent,” Thompson adds. “I couldn’t agree more. But — there’s really no money to be had.” Rep. Sherry Jones, D-Nashville, states that “the legislature was waiting for the federal government to act,” which never happened.

The question that must be asked, then, is what the proper response should be in the face of government apathy, not enough money, not enough volunteers, not enough laws, not enough equipment, and a very disturbing past. The answer, so far, lies almost entirely in grassroots community organizing. Nowhere is this more obvious than in the African-American community, where most leaders seem to feel that the only way the situation will improve is through increased voter education and awareness. “This is what happened,” the Rev. Edward Robinson of Nashville says. “Now we know how they threw away votes and took advantage of us. But you vote regardless of whether you go to the polls or not. . . . Politicians will only respond on how or whether we vote.”

The national NAACP has assigned voter empowerment coordinators to 22 states, working with a threefold purpose: to register, to educate, and to get out the vote. They’re working with people where they live, through the organizations vital to them — labor unions, black colleges and their sororities and fraternities, local NAACP branches, the Urban League, black employee networks, and community centers. They’re registering voters at neighborhood parades, festivals, tailgate parties, and beauty shops.

A 36-city NAACP bus tour traveled through the South this summer to promote voter awareness. It was as grassroots as grassroots can get, with activists speaking at high schools, driving through neighborhoods with bullhorns urging people to vote, and enlisting DJs at urban radio stations to push voter registration during evening drive-time.

“We don’t know how many people might have been disheartened by the events of last year,” says Paco Havard, Tennessee state president of the United Auto Workers civil rights council. “But we’re trying to do whatever we possibly can to get folks out to vote.”

And these techniques do work. In the 2000 election, the voting population of the state of Tennessee was 18% African-American, as compared to 13% in the 1998 elections. Statistically, this is an amazing jump, and it occurred before the unprecedented efforts of this year. “Our job is to teach the importance of voting,” says state coordinator Florence Howard. “We’re empowering people to be part of the American process. All citizens who have the right to vote, need to go vote.”

Organizations such as the Nashville Peace and Justice Center are also leading voter registration workshops. And throughout the country, but especially in the South, the participation of churches is a crucial factor. The Missionary Baptist Church in Tennessee alone consists of 400 churches with 300 to 6,000 people per church, all coordinating with the national NAACP to register, to educate, and to get out the vote. There is a strength running under the media radar, a steely determination to exercise the right to vote that so many struggled to win.

“I don’t know if the work I do on this issue will make a difference,” says Chris Lugo, a Nashville activist. “All I know is how I’d feel if I didn’t do it.”

Tags

Catherine Danielson

Catherine Danielson is the founder of United Progressive Citizens for Change, a non-profit organization in Tennessee dedicated to researching and publicizing the need for election reform. (2003)