Letter from the Editor: “No Effort to Attain Something Beautiful is Ever Lost”

This article first appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 30 No. 4, "The Right to Vote." Find more from that issue here.

On an overcast October day last fall, standing before a sparse crowd in the small northwest town of Tuscumbia, Alabama, Governor Don Siegleman had a momentous announcement to make.

The state was on the brink of becoming the 22nd in the country to issue its own specialized quarter, and the coin’s design, which Siegleman was about to unveil, would feature one of Alabama’s most gifted natives: Helen Keller.

The story of Helen Keller that was reported in the wake of Gov. Siegleman’s ceremony is one many people are familiar with. Born in 1880, Keller was abruptly struck at the age of 18 months with a brain fever that would rob her of hearing and sight for the rest of her life.

Keller’s courage in overcoming her deafness and blindness was legendary, and is what likely prompted school kids across Alabama to lobby the governor to feature Keller’s image on the coins, which will come out next April. As the governor said, “Helen Keller’s struggle and her optimistic spirit of determination represent all that is good in the human race and in Alabamians.”

The words rang true. But there’s another side to Helen Keller that wasn’t told at the press conference on the lawn of Keller’s Tuscumbia birth home, or in most media accounts that followed — even though it was the part of Helen Keller that perhaps most reflected the spirit of struggle and determination that made up her life.

Helen Keller was a radical. Swept up into the burgeoning labor, feminist, and other social movements of the early 20th century, from early on Keller proudly declared herself — to the chagrin of establishment figures who (often patronizingly) lauded her triumphs in the face of disability — a socialist.

Keller was unrelenting in her criticism of a society ruled by the wealthy few. She observed that “The country is governed for the richest, for the corporations, the bankers, the land speculators and for the exploiters of labor.”

The drive for profit, Keller believed, was connected to the drive for war. As she argued on the eve of the First World War, “The few who profit from the labor of the masses want to organize the workers into an army which will protect the interests of the capitalists.” Faced with a deadly conflagration between European powers, Keller called on the working masses — heavily influenced at the time by the militant Industrial Workers of the World, or “Wobblies,” and Eugene Debs’s popular Socialist Party campaign for president, both of which she fervently supported — to resist the war machine:

Strike against all ordinances and laws and institutions that continue the slaughter of peace and the butcheries of war. Strike against war, for without you no battles can be fought. Strike against manufacturing shrapnel and gas bombs and all other tools of murder. Strike against preparedness that means death and misery to millions of human beings. Be not dumb, obedient slaves in an army of destruction. Be heroes in an army of construction.

The great strikes didn’t happen, and war engulfed the world. U.S. politicians used the war as a pretext for crushing domestic dissent and the movements of which Keller was a part. Most infamous were the 1919 Palmer Raids, in which Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer arrested and otherwise destroyed the lives of thousands of supposedly “unpatriotic” Americans, targeting in particular 249 “resident aliens” because they had little legal recourse to resist.

But up until her death in 1968, despite the ebbs and flows of the “mighty mass movement,” Keller took comfort in having cast her lot with those fighting for justice and peace. As she once said, “Remember, no effort that we make to attain something beautiful is ever lost.”

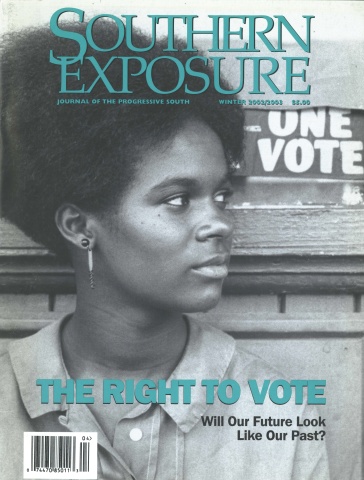

The Right to Vote

“We, the people, are not free. Our democracy is but a name. We vote? What does that mean? We choose between Tweedledum and Tweedledee.”

— Helen Keller, 1911

I’d bet an Alabama quarter that most people in this country, at one time or another, have felt the same way about voting as Keller did in 1911 — probably as we’re scurrying to our obscurely-located precinct, before or after work, wondering if it’s all worth the hassle.

One could say that millions of Americans answer the question of “is voting worth it” each campaign season through their actions. In the 2000 elections, roughly half of the nation’s voting-age citizens didn’t make it to the polls, which has left us with the lowest rate of voter participation in the industrialized world.

Maybe folks pass up the poll booth because they sense they’re not being given real choices. They are in tacit agreement with Ms. Keller, not to mention populist Jim Hightower, who titled his latest book “If the Gods Had Meant Us to Vote, They’d Have Given Us Candidates.”

Maybe so many of us boycott elections because of the near-total takeover of big money in politics, which has tipped the scales against average citizens so completely that we no longer see the point. Maybe it’s because it’s just so damn hard to register, read up on the candidates, and find time on election day to cast a ballot.

And surely some, consciously or not, side with Helen Keller’s anarchist fellow traveler and Palmer Raid deportee, Emma Goldman, who said: “If voting changed anything, they’d make it illegal.”

I’m sure that civil rights workers, such as those registering poor African Americans during Freedom Summer in rural Mississippi, pondered such questions as police clubs smashed against their heads and bullets riddled the houses and offices of those who dared to speak out for the franchise.

Organizers of the 1960s Southern freedom movement had few illusions about the purity of U.S. democracy. Indeed, as SNCC leader John Lewis — another great Alabama native — observed in his speech to the 1963 March on Washington, American politics is “dominated by politicians who build their careers on immoral compromises and ally themselves with open forms of political, economic and social exploitation” — a situation requiring not just marking a ballot every few years, but a “great social revolution.”

The young men and women who risked their lives for basic civil rights knew voting wasn’t everything. But they also understood the significance of the vote, not only as a tool of democracy, but also as a touchstone issue — like education or health care — that helps us understand broader conflicts in our communities and country.

Today, laws that strip millions (a disproportionate number of them black) of the right to vote due to felony convictions, even after they’ve served their time, are links in the chain of a prison-industrial complex that locks up a larger share of our country’s population than South Africa.

The system of legalized bribery called campaign contributions is merely one tool at the disposal of those who hold inordinate wealth and power in every facet of political and economic life. The lack of seriousness about voting reform at all levels of government, while millions are disfranchised, reveals a country that honors democracy more as mythology than reality.

While insisting on voting rights may help remedy the divisions and injustices in our country, voting alone can’t be expected to heal our social ills. Such change, we know from history, comes only when great numbers of people join together around a shared sense of purpose, and use every means at their disposal — not just the ballot box — to force change.

A symbol of our country’s ideals, a barometer of the state of society, an imperfect instrument for social change — voting is all of these, and more. As long as this most elemental building block of democracy remains under attack, we must defend the right to vote.

Tags

Chris Kromm

Chris Kromm is executive director of the Institute for Southern Studies and publisher of the Institute's online magazine, Facing South.