Freedom Is a Constant Struggle

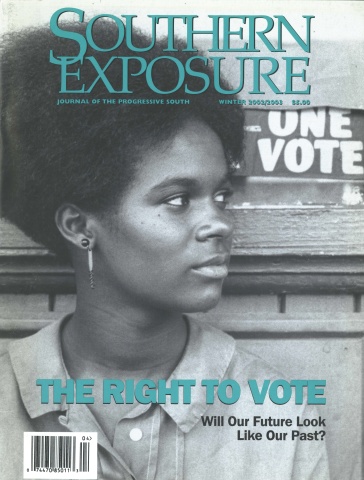

This article first appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 30 No. 4, "The Right to Vote." Find more from that issue here.

In 1964, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), together with the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), the Congress on Racial Equality (CORE), and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), put out a general call for volunteers to work for voter registration in the Deep South. The response was tremendous — thousands answered the call. Protected by this human shield of mostly white students, young African-American activists were able to organize and develop local leadership. Some of the black activists, like Muriel Tillinghast, stayed on after the volunteers went home.

Tillinghast had already worked with a SNCC affiliate, the Nonviolent Action Group, to desegregate lunch counters and rest stops along Route 40, the Washington-Maryland highway that was traveled by African consular staff. As soon as she graduated from Howard University, Tillinghast went to Mississippi, where she worked as a SNCC project coordinator for two years.

Three days after I graduated, I decided I was going to Mississippi. I didn’t know what was going to happen after that, but I was definitely going to go. Now, it was already bad enough that I had let my hair grow natural — that eliminated about 90 percent of the discussion in my house — but when I decided to go to Mississippi, everyone got on my case. My parents, my family — people weren’t talking to me.

We knew that something momentous was occurring down South. People were operating in very small groups, but they were operating in many places. At that point the press had not yet decided what political perspective they were going to take on the events in the South, so they were actually showing all this activity on television. This was a source of encouragement for us and helped to tie the lines of communication together. Of course, that didn’t last. Later on, I’m sure the press boys sat down in a large room and said, “Enough of this, let’s move on.”

Now, I was basically a Northerner — folks from Washington, D.C., like to think that they’re from the North. I had already had some experiences on the eastern shore of Maryland, which will let you know immediately that you’re not North, but I hadn’t really gotten ready for Mississippi. We all spent a week at the orientation center in Oxford, Ohio. SNCC sent up its people, who told us all these tales about what folks had to go through just in terms of a normal life struggle. We knew that Mississippi was going to be a special place. And for all of us who went, we know that we didn’t come back the same.

Heading South

So we went to Mississippi after spending a week getting ready for something you really couldn’t get ready for. We headed in on Greyhound buses. People were singing and talking and joking around on the bus, but when we hit that Mississippi line there was silence. People got dropped off at various projects one by one in the dead of the night. I was dropped off in Greenville. We made a point of distinguishing Greenville from Greenwood. Greenville was relatively liberal. If you were in Greenwood, you were in deep. I still had hope.

In all honesty I spent my first two weeks in the office upstairs because I didn’t know quite how I was going to survive Mississippi. After a while it dawned on me that I would never get anybody to register that way, so I started coming downstairs and cautiously going out into the town. I functioned like a shadow on the wall, just getting used to walking in the streets.

Charles Cobb was my project director. About a month after I got to Mississippi, Charles looked at me and said, “You know, I want to do something else. So, I’m going to leave you in charge of this project. You look like you can handle it.” Right, sure thing. . . .

I was in charge of three counties: Washington, Sharkey, and Issaquena. In Mississippi, you learn the county structure like the back of your hand, because the basis of power politics is the county structure. Greenville, which was the base of our operations, was the Washington County seat. It was the town in a county of hamlets. Sharkey County was the home of the Klan in that part of Mississippi. Issaquena was a black county, and it was sort of discounted at the time.

By and large we took our mandate from Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Toure), who was the project chief in our area. We were young, and we were just beginning to learn what politics and power were all about. We began to find out that power is monolithic, particularly in places where there is not a lot of competition.

People in Mississippi knew about us long before we had even gotten there. We didn’t realize it at first, but we were under constant surveillance. For instance, a young white volunteer was doing some research at the library, which was in the same building as the police station, on the second floor. As she was coming out of the library, the police chief said to her, “Come here, I want to show you something.” He took her to a room, and in that room was a file drawer, and in that file drawer were pictures of everybody in our project. We had no idea that they were watching us this closely. And they had pictures of every kind of activity, taken day and night, because they were using infrared.

Well, these pictures may not mean anything right now, but there were times when the political pressure really got to us. For example, we had some young gay men who were in our project, and I remember very tearfully putting one of them on the bus. He said, “Muriel, I can’t have those pictures shown.” I didn’t even know that anything was going on, but the bottom line is that everybody’s privacy was invaded. And that’s before we had even registered anybody to vote.

In these little country towns, as soon as a foreign-sounding motor comes across the road in the middle of the night, people know that a stranger is there. You need never make an announcement. You can stay in the house all day — someone knows. “I heard a different motor last night. It stopped about two doors down the street.” And they start making inquiries. There were instances when the police just opened the door and came through the house looking for us and never said a word to any of the people who lived there. Not that they were going to rough us up at that point, but someone knew that someone was keeping company with people who weren’t local.

In order to encourage people to vote, we had to explain what was going on in the country and why they were in the situation that they were in. We tried to convince them of the importance of their participation in the voting process by showing them who was actually on the voting rolls — for instance, half the local cemetery! Sometimes we were able to register only a few people — why risk your life simply to sign a piece of paper or register at the county courthouse? — but as people gradually came to trust us, they would talk to their neighbors, and the numbers swelled.

The Heart of the Black Belt

Later I moved out of Greenville and into Issaquena County. Until I got to Mississippi, I didn’t know anything about black counties. I began to find out that there were these towns like Mound Bayou outside of Holly Springs where blacks had settled after the Emancipation Proclamation and established their own base.

Most people in the North don’t understand why blacks are so poor. They don’t realize that when black people left slavery, they left with nothing -1 mean nothing. Whatever they were wearing, those were the clothes that they took with them into their new life. Whatever beans or seeds they could gather, that was going to be food. They didn’t own the land they were standing on — they were immediately trespassing. And in Mississippi trespassing was serious crime — as serious as selling a kilo of cocaine in New York City today. You were going to go to jail and your minimum time was going to be five years — just for standing on the land.

So the people had to move, and when they moved, they moved under pain of death, because the same people who had always kept black people enslaved were again at work hunting down those bands of blacks who were leaving by foot. Black people had no way of defending themselves. They had to travel by night, gathering up at certain places — word gets around on the grapevine. And they began to establish themselves in various places, even in the state of Mississippi. Issaquena was one of those places. It was sort of a long county, and very sparsely settled. Counting everybody standing up, the county seat at Mayersville had 50 people.

Some of you may be familiar with the name of Unita Blackwell. She made a name for herself over time as the mayor of Mayersville and as an activist, but when I met Unita, she was just an ordinary housewife. She and her husband, Jeremiah Blackwell, were the first ones to offer us a safe haven in Issaquena. That’s really how we operated. We would be invited in by one household, and based on that household’s sense of us as individuals and where we were going as an organization — because they knew that we were not alone — they would introduce us to someone else. This would be our next contact. And if this sounds like we were operating under war conditions, we were. You did not talk to anybody unless someone said it was okay. And it wasn’t that obvious who was safe to talk to, because you never knew if you were talking to the State Sovereignty Commission.

The State Sovereignty Commission was an intelligence-gathering force. It was set up by the government in the state of Mississippi. Hundreds of thousands of dollars of state taxpayers’ money — including black taxpayers’ money — was used to finance all this surveillance. It was responsible for gathering and spreading disinformation early in the game. Early on we thought it was misinformation — that they just didn’t get it straight — but it was really disinformation that was deliberately designed to undermine public support for the activities that we were engaged in. You had to be careful about who you spoke to because you could be trailed back to your base. Wherever you were staying, those people were as vulnerable to midnight raids as you were on the streets. So when they allowed you to sleep on their floor or in their best bed in the corner of their house, whatever the accommodations were, they were putting themselves in jeopardy. As Bob Moses used to say, “Mississippi needs no exaggeration.” It was its own exaggeration.

I remember one family of cotton pickers that I stayed with — two adults and five kids. They were in Hollandale, a nasty little town on the highway between Greenville and Mayersville. This family was at the very bottom of the economic ladder. They worked by permission on someone else’s land. They worked from sup sun up to sun down with no breaks. It was as close to slavery as I hope to ever see in life. I usually made a point of eating somewhere else, but one night they said, “No, you eat with us.” I’ll never forget that dinner. It was cornbread and a huge pot of water into which they cut three or four frankfurters. For them that was a good dinner.

Founding a Freedom School

We also started a Freedom School. Why? Well, out of natural curiosity schoolchildren wanted to know, “Why can’t we vote?” So there was a need to put this particular situation into some sort of historical context. And as you talked about the history of black people in this country, you began to see another kind of development taking place in the young people. Before, they would let certain things in school go by unchallenged. They might not like something, but they wouldn’t question it. Our presence gave them a support base, and they began to have the courage to say certain things, or not to read certain things, or to bring other materials to the classroom. This was unheard of. And it wouldn’t take long before those kids would be sent home, first one kid, then another, and by the time a week had passed, there would be 20 kids who had been told by the principal, “Don’t come back!”

Now the school system was segregated — these were black kids in black schools — so how could this be happening? To understand that you have to understand the power relations in the South. You don’t get to be a black principal in a black school in Mississippi unless you are an acceptable political commodity — pure and simple. And you quickly become unacceptable when you start having alien thoughts, like why can’t we register to vote and what is this “grandfather clause,” anyway — just normal conversation. But that wasn’t considered normal conversation, that was considered subversive, and these young people had to be plucked out before they spread the cancer to the rest of the student population. So even though most of us tried to maintain a low profile, it didn’t take long for brush fires to occur.

Sheriff Davis Builds a Jail

Even though Issaquena was a black county, all the people who had any power were white, including Sheriff Davis. When our paths crossed, which they did all too frequently, we would greet each other — “How ya doin’?” — because Mississippi is country-like in that way. The first time I saw Sheriff Davis coming down the road he was in a pickup truck. By the next week the pickup truck had a kind of metal grating on the top. One day he stopped me and said, “You like that, you like what I got? Well, that’s for y’all.”

And then Sheriff Davis told us that he was building a one-room jail out of cinder blocks — just for us! And did we like that? It was big enough to stand up in, you could also sit down, and of course it was out there in the middle of the hot sun. When we told him he was really wasting his time, Sheriff Davis said, “Well, I know you’re gonna do something. I know you are, and I’ll keep up with you.” Sometimes when we would go walking down the street, there was Sheriff Davis’s car, coming right behind us. He’d sit in the front and wait, and sometimes we’d go past the person’s house and go to somebody else’s house in the back, because we didn’t want to lead him directly to our next possible registrant.

I don’t think we understand what people risked when they took those steps. As soon as we had made contact with people, as soon as they went to the courthouse to register, their boss would be right there. If they worked in the cotton fields, oftentimes they were dismissed immediately. Or they’d be cut off from their welfare rations. The power system was consolidated on the notion that no, you will not move up, you will not challenge us in any way.

Welcoming the Klan

Then we began to look at other things that were going on. Why could some people plant cotton when others couldn’t? There were these gentlemen farmers who planted nothing but made an awful lot of money, and then there were people who were planting cotton but were barely able to get it ginned. So early on, we began to deal with the cotton allotment system. Well, when we began to run people for the cotton allotment board, we hit the economic bell. And that brought out the Klan.

Sometimes the Klan seemed benign compared to some of the other rabid, racist organizations, like the Preservation of the White Race, who made no bones about the fact that if they saw you, they were going to kill you.

One time I called a meeting of tractor workers, thinking that I was going to organize black tractor workers, and I walked right dead into a nest of Klansmen who had gotten the same word, but didn’t realize the meeting was for black workers. I don’t know who had told them, but they were there. As I approached them in my car — carefully — I was wondering who all these white men were standing at the church steps. They knew something was wrong because the place of the meeting was a black church, and they didn’t look happy. I kind of looked at them. They kind of looked at me. I said, “You here for the meetin’?” And they said, “Yeah, you called the meetin’?” I said, “No. I’m just looking for the person who called the meetin’.” And I backed on out and left.

All of us learned how to be patient, how to play for the occasion, because your life could turn on a dime. Later you might laugh, but at the time it wouldn’t seem so funny. Like the time I ran into the police car. Now, you should have seen me jump out of my car all incensed, carrying on about this and that, with this poor white volunteer sitting next to me. He just knew we were dead. But this policeman was so disgusted with me that he just told me to get a move on.

Life Lessons

One of the things I have learned about doing political work that you may not be serious about it, or you may not know how serious a step you’re taking, but when the opposition sees anybody treading on their territory, they’re always serious.

We had so many near misses, so many close calls, and we had nobody to depend on but ourselves. If you had a problem you sure couldn’t call a cop! Which is almost the same situation that the black community faces in the inner cities today. If you have a problem and you call the cop, the cop is going to give you a bigger problem. So we learned to handle things ourselves as best we could.

Most of all we learned that people in Mississippi were a very special group of people. They were our country’s peasant base. They were incredible in their wisdom, and many had extreme courage. I can remember this guy, Applewhite. Now Applewhite was a placid, nondescript kind of guy. You were never quite sure whether what you had to say registered or not. I didn’t like riding with Applewhite because I felt that if I was going to get pushed into something, I was going to be on my own. One day we were riding down the road, and I said to Applewhite, “Do you have anything in this car in case we get stopped?” Well, you would never know what was going on in Applewhite’s head — he had a perfect poker face. “Open up the glove compartment,” he said. “Check down underneath the seat on my side. And on your side. Listen, we may not survive, but we sure could blaze a few holes.” I said, “That’s the way I want to go.”

I learned that people aren’t always what they appear. At the time you’re trying to organize them, they’re trying to figure out where you are in this constellation of players. Are you going to be around when the action goes down? Am I talking to the State Sovereignty Commission? And essentially, is what you’re telling me true? That’s why we always encouraged people to read. We always encouraged people to discuss. Nothing that we did was cloaked in any kind of secrecy, which is the way I’ve continued to operate.

So that was my life for two years. It was about day-to-day survival but it was also about how you transform a community that really had not been touched in over 100 years by any outside force — how you get it to join the twentieth century and get enough players inside that loop to be able to carry it on after you leave. On the whole, I think we were very successful. We paid some very, very high prices for it, but I think most of us would have done it again.

Tags

Muriel Tillinghast

Muriel Tillinghast was the 1996 vice-presidential candidate on the Green Party ticket in New York. (2003)