This article first appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 30 No. 3, "Underground Pastime: The Hidden History of the Negro Leagues." Find more from that issue here.

On a warm April night in 1998, the Durham Bulls’ ballpark was the scene of a tribute to the Negro Leagues. To throw out the ceremonial first pitch, the Bulls recruited Buck O’Neil, longtime first baseman, manager of the Kansas City Monarchs, and charismatic public face of the Negro Leagues ever since his appearances in Ken Burns’ Baseball documentary (1994). The 86-year-old O’Neil stood on the pitcher’s mound, and began to wind up. He stopped himself mid-stride, shook his head, and trotted a few feet closer to home plate. Again he raised the ball, aimed — but no, still too far. With impeccable timing (reminiscent of the “comedy baseball” teams he played for in his youth) he made his way closer and closer to the plate until he finally placed the ball gently in the catcher’s mitt. The crowd roared.

The Bulls and their opponents wore Negro League uniforms that night, each from a different team: Homestead Grays, Atlanta Black Crackers, Memphis Red Sox, Chicago American Giants, Nashville Elite Giants, Pittsburgh Crawfords, Birmingham Black Barons. From the stands, it was hard to distinguish between the mostly white and gray uniforms. Everybody took home a souvenir Monarchs cap.

Some sixty years earlier, a Durham Bulls ballgame was the scene of something quite different. On an August night in 1937, 4,000 spectators crammed into a much smaller ballpark, ostensibly to see the Bulls play the Rocky Mount team, but really to enjoy a rare visit by Al Schacht, the famous baseball clown. When white fans overflowed the seats normally set aside for them, team officials ordered black patrons to make room by moving into distant outfield bleachers. According to the Carolina Times, a local African-American newspaper, the black fans balked, argued with ushers, and demanded refunds. Most of them left the park angrily. Many said they wouldn’t be back. “One thing is sure,” one fan told the Times. “Durham colored people will not suffer for the want of seeing a first class ball game. To my [knowledge], the Durham Black Sox [the local black team] play just about as much baseball as the Durham Bulls. In fact, I believe the Bulls would be unable to defeat the Black Sox anyway.”

The Durham Bulls still play, in a sparkling new park with plaques honoring great African-American players. The Durham Black Sox, meanwhile, have vanished into the Jim Crow past. Virtually every night on some cable channel somewhere, the Susan Sarandon-Kevin Costner film Bull Durham memorializes the Bulls as the quintessential minor league baseball team. And every summer, African American and Afro-Latin ballplayers take the field at the new Bulls’ park to play before crowds that are still mostly (though not entirely) white — in a city that’s half black.

Even non-baseball fans are aware that once, in the United States, black men weren’t allowed to play in what’s known as “Organized Baseball.” They probably know Jackie Robinson as the quick-witted, slashing second baseman who finally jumped the color barrier in 1947, and bow-tied, bespectacled Branch Rickey of the Brooklyn Dodgers as the executive who dared to sign him. Depending on their historical knowledge and political orientation, they may even class the integration of baseball with Harry Truman’s integration of the armed forces as important precursors of the civil rights movement, and may celebrate Robinson as a predecessor of Rosa Parks and other activists. “Jackie as a figure in history was a rock in the water, creating concentric circles and ripples of new possibility,” Jesse Jackson said in his eulogy at Robinson’s funeral in 1972. The sportswriter Grantland Rice claimed that, “[n]ext to Abraham Lincoln, the biggest white benefactor of the Negro has been Branch Rickey.”

Where does this leave those who came before Robinson, those who, in the words of the late Ted Williams, “weren’t given the chance?” Fans and non-fans alike may know the names Satchel Paige and Josh Gibson, great players who were tragically excluded during their primes (Gibson died before he got the chance to play in the white majors; in 1948, Paige entered the American League, at 42 the oldest rookie in history).

But Jim Crow-era black baseball consisted of much more than a few stars. And, far from unremitting tragedy, its story is one of self-determination and collective success against great odds. Black ballplayers sustained a level of craftsmanship (some might call it artistry) that classes them with the creators of jazz or the writers of the Harlem Renaissance as makers of African-American culture during a time of especially harsh oppression.

The vast and still largely unknown world of black professional baseball in the era of segregation, roughly from 1860 to 1960, has come to be known collectively (and somewhat inaccurately) as the Negro Leagues. For decades, African Americans sustained a whole alternate universe of owners, umpires, managers, coaches, and sportswriters, minor as well as major leagues, traveling and city teams that fed into the organized leagues, even a few ballparks built solely for black teams, such as Greenlee Field in Pittsburgh and White Sox Park in Los Angeles. According to the historian Donn Rogosin, the Negro Leagues “rank among the highest achievements of black enterprise during segregation.” Professional baseball afforded the best players a status, a range of experience, an income, and sometimes a freedom rare for African-American men in the Jim Crow era.

The Negro Leagues constituted one of the most important networks of a national black culture in the first half of the twentieth century, spanning the continent and prominently including Southern teams and leagues. Unlike the white major leagues, African-American baseball, of necessity, crossed color lines, class and regional boundaries, and national borders. Professional black teams took on all comers, from white college and semipro teams to major-league clubs, from industrial teams to local amateur “nines”, and played before crowds of all varieties — sometimes white, sometimes black, often mixed. Teams and players traveled thousands of miles and played in many countries, from Venezuela to Canada, occasionally ranging as far as Japan. Far more so than the white majors, Negro Leaguers experienced the lived reality of baseball as a truly national, not to mention international, pastime.

Since the 1970s, the Negro Leagues have received a sort of dutiful attention from the baseball establishment and the public at large. Yet despite the dedicated efforts of Negro League historians, the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City, the organizers of “throwback” days like the one held at Durham and other ballparks, and the ex-players themselves, the general understanding of black baseball (especially that of the mostly white fan base) remains vague, condescending, and focused on a small number of mythic figures, such Gibson, Paige, or James “Cool Papa” Bell. The public’s reception of the Negro Leagues revival resembles mainstream culture’s attitudes toward Native Americans: the Negro Leagues can now safely be honored precisely because they have been vanquished.

Like most history, baseball history is written from the point of view of the victors, so it’s no surprise that the Negro Leagues are typically seen as little more than a regrettable embarrassment, a “cruel American anomaly,” as one historian has put it. That the Bulls and not the Black Sox still play seems like nothing more than progress; the natural course of history.

But the closer one looks at African-American baseball in its broadest social context, the more apparent it becomes that integration under white auspices may have destroyed far more than it created — and the more the Negro Leagues, compared with the hermetic, self-referential world of the white-controlled majors, look like the diverted and forgotten mainstream of early twentieth-century baseball history.

The 19th Century: Jim Crow on Deck

African Americans have been playing baseball for nearly as long as the sport has existed. When blacks first took up baseball, the game was played barehanded. A catch on one bounce was an out. There were no called balls: the pitcher threw the ball until the batter found a pitch he liked. No one knew how to throw a curveball, and it would have been illegal anyway: the pitcher was required to throw with a stiff, underhand motion, with no wrist snaps or twists to give the pitch movement. Playing grounds weren’t enclosed, admission wasn’t charged, and players weren’t paid.

Modern baseball first arose in New York City in the 1840s as a strictly segregated social activity. We hear first, not about black players, but about black teams. The first confirmed game between black teams was played in 1860, but it wasn’t until after the Civil War that baseball’s popularity exploded, and African-American clubs sprang up in Philadelphia, Washington, D.C., and New Orleans. Like the earliest white clubs, black baseball teams such as the Washington Mutuals and the Philadelphia Pythians were amateur, quasi-fraternal organizations, dedicated to socializing and the promotion of middle-class values and aspirations as well as to athletics. As much care and attention were lavished on the post-game banquets as on the games themselves.

African Americans challenged segregated baseball almost from the beginning. In 1867, the Pythians, managed by teacher and community leader Octavius Catto, applied to join the amateur, all-white National Association of Base Ball Players. In response, the Association drew the first explicit color line in baseball, prohibiting “the admission of any club which may be composed of one or more colored persons.” Catto’s Pythians didn’t last, but other clubs sprang up. And, barred from white baseball, they began to form leagues of their own.

As early as 1881, an organization of amateur black baseball clubs called the Union League was operating in New Orleans, followed in 1886 by the “Southern League of Colored Base Ballists,” a professional league including teams from Memphis, Atlanta, Savannah, Jacksonville, Charleston, New Orleans, and Montgomery. The following year, newspaperman Walter S. Brown founded the National Colored League, an ambitious circuit composed of eight teams from Louisville to Boston. The League foundered after only 13 days, but even in that short time it managed to showcase the depth of African-American baseball talent across the country.

The Negro Leagues: A Scorecard

MAJOR LEAGUES

Negro National League I (west and south) 1920-1931

Eastern Colored League (east) 1923-1928

American Negro League (east) 1929

East-West League 1932

Negro Southern League (west and south) 1932

Negro National League II (east) 1933-1948

Negro American League (west and south) 1937-1960

MINOR LEAGUES

Southern League of Colored Base Ballists 1886

National Colored League 1887

Negro Southern League 1920-?

Negro Western League ca. 1921

Texas Negro League ca. 1929

Texas-Louisiana League 1931

United States League 1945

Negro Florida State League late 1940s

Negro American Association late 1940s

West Coast Association (a.k.a., Negro Pacific Coast League) late 1940s

Even as all-black teams and leagues proliferated, more and more individual black professionals were slipping into white baseball. We’re taught that Jackie Robinson broke the color line, but in fact he had a nineteenth-century predecessor. In 1883, Moses Fleetwood Walker, an Oberlin graduate and skilled catcher, signed with the Toledo club, which a year later joined the white American Association, then a major league. Sixty-three years before Robinson, Fleet Walker became the first black major leaguer.

Although Walker only spent one season in the majors, by 1887, 14 African Americans were playing in white baseball, seven of these in the International League, the top minor league at the time.

These weren’t easy jobs to get or keep. As The Sporting Life admitted in 1891, “An African who attempts to put on a uniform and go in among a lot of white players is taking his life in his hands.” It was said that Frank Grant, who joined the minor-league Buffalo Bisons in 1886, was so terrorized by opposing players sliding into second with their spikes held high that he began strapping wooden shields to his shins — thus inventing shin guards, later a staple of catcher’s equipment. “The runners chased him off second base,” said one anonymous player to The Sporting Life. “They went down so often trying to break his legs that he gave up his infield position and played right field.” One white player, Ed Williamson, even claimed (though he was likely exaggerating) that the feet-first slide was developed specifically to attack Grant.

Grant led the league in home runs and played a brilliant second base. Robert Higgins, a black pitcher who signed with Syracuse, overcame racist teammates’ sabotage (playing poorly and intentionally committing errors when Higgins was on the mound) to win 20 games. Another African-American pitcher, George Stovey, won 35, which still stands as the International League record.

But the death knell of integrated baseball in the nineteenth century sounded on July 14, 1887. The International League’s Newark team, featuring an all-black pitcher-catcher duo of Stovey and Fleet Walker, had scheduled an exhibition game against the defending National League champion Chicago White Stockings. Chicago’s manager, Adrian “Cap” Anson, refused to take the field unless Stovey and Walker were removed. The Newark manager caved in, benching his star pitcher. On the very same day, the directors of the International League met in Buffalo and voted to bar the signing of any additional black players. Although African-American players lingered on minor league rosters until 1899, 1887 proved to be the turning point.

The future of black professional baseball lay elsewhere. Although all-black leagues weren’t able to scrape together enough capital to survive in the late 1800s, individual black teams could. In July, 1885, the Argyle Hotel, a Long Island resort, hired a newly-formed black semipro team from Philadelphia called the Keystone Athletics, to provide entertainment for guests. A month later, the team merged with two other prominent clubs from Philadelphia and Washington, D.C., took the name Cuban Giants, and became the most famous professional African-American baseball team of the nineteenth century.

That name would reverberate throughout the history of black baseball. The team was probably named after the white New York Giants. How the black Giants, all of them U.S.-born, became “Cuban” is a bit murkier. One story has it that when the team took to the road, they decided that representing themselves as Cubans, rather than black Americans, would make them more palatable to whites in small towns. (In the antebellum era, light-complected slaves sometimes passed as “Spanish” in order to escape.) To sustain the illusion, they may have spoken a sort of mock Spanish gibberish to each other on the field.

Due in part to the popularity of the Cuban Giants and their imitators, the word “Giant” itself came to mean “black ballplayer” to the sporting public. During an era when mainstream newspapers rarely printed photographs of African-American athletes and often relegated coverage of black sports to brief notices or lists of scores with little detail, fans could know for certain that almost any team called “Giants” was black. In the early 1920s, Chicago’s two major African-American teams were the Chicago Giants and the Chicago American Giants; meanwhile, a white semipro team had to bill itself as the “White Giants” to avoid confusion. “Stars” and later “Monarchs” also became popular names, but never could match the appeal of “Giants,” which appeared everywhere from Boston and Atlantic City to Asheville and Miami.

Clowns and Minstrels

Baseball was one of the most important elements of a pre-television culture of live professional entertainment, which included vaudeville, theater, jazz and dance hall music, circuses, and other sports like boxing and horseracing. The best African-American teams were far more in touch with this everyday milieu than their white equivalents.

Frequently baseball mixed with these other forms of entertainment. James Weldon Johnson, the novelist, musician, and author of “Lift Every Voice and Sing” (the Negro National Anthem), who saw the Cuban Giants in his youth, wrote that the team “brought something entirely new to the professional diamond; they originated and introduced baseball comedy. The coaches kept up a constant banter that was spontaneous and amusing. They often staged a comic pantomime for the benefit of the spectators . . . [and] generally after a good play the whole team would for a moment cut the monkey shines that would make the grandstand and bleachers roar.”

All kinds of spectacles served to augment a team’s drawing power. The Page Fence Giants, sponsored in the 1890s by the barbed wire manufacturer and organized by Bud Fowler, the first black professional baseball player, bicycled to the ballpark wearing firemen’s hats to attract a crowd. Even the Lincoln Giants of New York City, a talented team starring two future Hall of Famers (Joe Williams and John Henry Lloyd), indulged fans with pantomimed “shadow ball” routines before games. The All Nations Club, based in Des Moines, Iowa, and later Kansas City, put on jazz shows after games, featuring the famous Cuban pitcher Jose Mendez on cornet. Players might stage throwing contests or footraces with local athletes. In the 1930s, Olympic hero Jesse Owens attracted crowds to Negro League games by running exhibition races against (as one player put it) “cars, motorcycles, racehorses, and guys from college.”

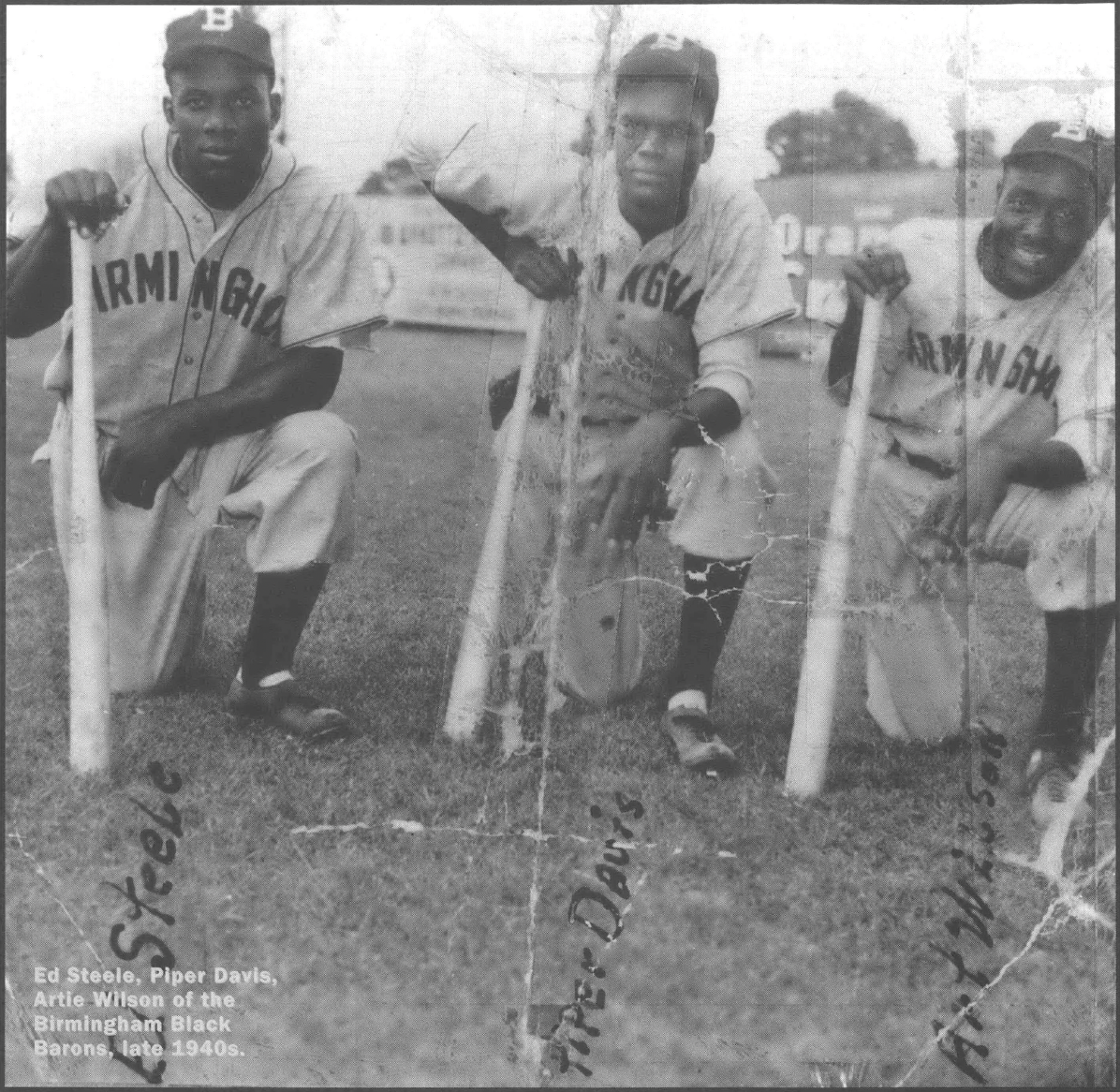

The organized Negro Leagues discouraged such spectacles, and to many players comic routines were degrading and fueled stereotypes. “If you were black, you was a clown,” recalled Birmingham Black Barons’ infielder Piper Davis in Southern Exposure in 1977. “Because in the movies, the only time you saw a black man he was a comedian or a butler.” “They had special guys for that, people who called themselves clowns,” Andrew “Pullman” Porter, a Nashville Elite Giants’ pitcher in the thirties, remembered. “You ask one of the ballplayers to go out and do something like that, he’d have a fit.”

In lean times, even the most successful African-American teams sometimes resorted to comedy and other stunts to bring in the crowds, as in the Depression or the 1950s, when the leagues struggled in the wake of integration. White semipro clubs noted the lure of novelty, as in the case of the House of David, a Michigan Christian sect that organized a baseball team as an advertising and moneymaking venture. The House of David teams were skilled, sometimes featuring former major leaguers such as Grover Cleveland Alexander; but most fans seem to have simply enjoyed the spectacle of longhaired men in flowing beards (which they wore as a religious obligation) playing baseball. The Kansas City Monarchs, among the proudest and classiest of Negro League teams, toured with the House of David in the 1930s, playing dozens of games through Canada, the Pacific Northwest, and the upper Midwest, and occasionally joined them in another House of David specialty: donkey baseball.

At the racially-fraught margins of the entertainment and sports worlds, early African-American baseball sometimes found itself elbow to elbow with minstrelsy, a popular and intensely racialized combination of music and entertainment in which usually white (but also sometimes black) performers caricatured African-American cultural forms. “Baseball minstrelsy” was exemplified by popular touring teams like the Tennessee Rats, who combined baseball comedy with evening variety shows, or the Louisville-based “Zulu Cannibal Giants Baseball Tribe,” who wore face paint, red wigs, long hair, and grass skirts.

The most successful of the race comedy teams was the Indianapolis Clowns, a sort of baseball equivalent to the Harlem Globetrotters (who fielded their own baseball team). But the Clowns played well enough between the comedy routines that they eventually earned a place in the Negro American League, and became major-league slugger Hank Aaron’s first professional team in 1952. The team survived the demise of the Negro Leagues and still operated, simply as “The Clowns,” in out of the way venues into the early 1970s — the last ghostly vestige of a rich, if troubling, tradition.

On the Road

African-American players moved freely between several baseball worlds. They played for and against all-black teams in the United States, after 1920 in organized leagues that included teams from the South. They played white major and minor leaguers in wildly popular exhibition games and in integrated independent leagues. They played in winter leagues in California and Cuba, they played in the Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico, Panama, and Venezuela. Negro League teams traveled (or “barnstormed”) through the South, the Southwest, Canada and the Pacific Northwest, even Mexico and on occasion East Asia. They played college and semipro teams, both black and white. A black player in the 1920s or 1930s might play 250 or more games a year (compared to the 162-game schedule of today’s major leaguers). It’s fair to say that many Negro Leaguers played over a longer stretch of the year, over a greater expanse of the globe, and possibly before larger numbers of fans than their contemporaries in the white National and American Leagues.

Beginning in the 1890s, black teams barnstormed from coast to coast and played nearly year-round, developing a road-wise culture unique to marginalized baseball. Some teams, such as Gilkerson’s Union Giants in the 1920s, lacked a home field entirely. Even organized leagues at times featured perpetual traveling teams, like the western Cuban Stars and Joe Green’s Chicago Giants in the Negro National League of the early 1920s. A decade later, when the leagues collapsed under the strain of the Depression, even an established team with a supportive community, the Kansas City Monarchs, took to the road for several years.

By then, cash-strapped owners had begun to go beyond the usual weekend doubleheaders, trying to squeeze more out of their already overworked players. “We’d play three games at a time, a doubleheader and a night game, and you’d get back to the hotel and you were tired as a yard dog,” Hall of Famer Judy Johnson said. Black-run hotels could usually be found in larger cities, but thanks to segregation, elsewhere Negro Leaguers were forced to find boardinghouses and families willing to put them up for a night or two.

Or teams might not find a place to stay at all. “Some places we couldn’t get nothing to eat, some places you couldn’t sleep, so we’d just ride all night,” said John Gibbons, who pitched in the Negro Florida State League in the late forties. “The conditions wasn’t too awful good,” said Ray Miller, who played for the Louisville Black Colonels. “Like you might play half the night and it’ll be 12 o’clock when you get through playing and you don’t know where you’re gonna get to wash up. You may have to ride another hundred miles or so.” Players themselves often drove the team vehicles, sometimes all night, before playing exhausted the next day.

Eating posed challenges, so players often had to take food to go, picking it up at a back or side door. When Rube Foster’s American Giants toured the West Coast, an Oregon restaurant refused to serve his team; after a lengthy argument, they supplied the players some snacks to eat outside. “Rube Foster’s Team Starving in Oregon,” blared a Chicago Defender headline. “American Giants Forced to Eat Crackers and Cheese. . . . The Mighty Rube Foster Fed on Tidbits.” Nap Gulley, a pitcher for Birmingham and several other teams in the 1940s and 1950s, remembered “wondering if I can eat here or can I go in the back door there or can I sleep in this place. That’s quite a burden for a ballplayer or anybody to carry around and still be able to produce without anger.”

As lynchings proliferated and the Ku Klux Klan flourished, the South preserved a reputation for especially intense racial hostility. In Mississippi during the thirties, members of the Philadelphia Stars were shaken to overhear a young African-American boy evidently being tortured and killed by whites at a gas station. In 1923 John Claude Dickey (known as “Steel Arm”), a brilliant young pitcher for the Montgomery Grey Sox, Knoxville Giants, and St. Louis Stars, was stabbed to death by a white man in Etowah, Tenn. The killer fled to a town called Cooper Hill, Ga., which, according to the Chicago Defender, was “dangerous for any person of color to even pass through in the day time.” It’s uncertain whether he was ever punished. Still, segregation and racism were hardly unique to the South. As Jesse “Mountain” Hubbard remarked, “In Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, shoot, I’d just as soon be down in Georgia.”

The barnstorming life was tough, but it helped knit together a national (and international) baseball network. Black baseball lacked the massive hierarchy of white organized ball, with its several levels of minors feeding the big leagues at the top; instead it had touring, which enabled the best teams to come in contact with the best young talent all over the continent. The baseball historian Bill James even argues that “the networking system by which the Negro Leagues identified and developed talent . . . appears to have been probably more effective than the methods used by the white teams.”

Barnstorming also became a vehicle for intercultural contact, bringing together unlikely combinations of teams and fans, and giving isolated locales in the upper Midwest or the Pacific Northwest a taste of cosmopolitan life. In small towns, the local amateur or semipro nine often served as a communal focal point, providing the most reliable source of public entertainment, and visits by African-American barnstormers were celebrated local events. Negro Leaguer Josh Johnson told an interviewer, “Back then — in the twenties, thirties, and forties — every town in western Pennsylvania and Ohio and Kentucky and, they tell me, Illinois had a ball club — town team. They’d go out and load up their lineups when we were going to come through. We’d play a guy here one night and the next day he’s over in the next county playing for them. They were proud of their teams and a lot of times the whole town would close up; everybody would converge on the ballpark.”

“Today we must balance the tears of sorrow with the tears of joy, mix the bitter with the sweet in death and life.

Jackie as a figure in history was a rock in the water, creating concentric circles and ripples of new possibility. He was medicine. He was immunized by God from catching the diseases that he fought. The Lord’s arms of protection enabled him to go through dangers seen and unseen, and he had the capacity to wear glory with grace.

Jackie’s body was a temple of God, an instrument of peace. We would watch him disappear into nothingness and stand back as spectators, and watch the suffering from afar.

The mercy of God intercepted this process Tuesday and permitted him to steal away home, where referees are out of place, and only the supreme judge of the universe speaks.”

— Jesse Jackson, eulogy at Jackie Robinson’s funeral, October 27, 1972

Underground Baseball

By the 1930s, harbingers of integration were appearing even in the small-town Midwest. North Dakota, of all places, became a hotbed for integrated semipro baseball, attracting some of the best talent, black and white, in North America. The integrated 1935 Bismarck, N.D., team assembled what might have been the best pitching staff in the world, featuring two Hall of Famers (Satchel Paige and Hilton Smith). In 1934, the Jamestown, N.D., club hired Ted “Double Duty” Radcliffe as the first African-American manager of an integrated team in the United States. The Denver Post sponsored a semipro tournament that featured black, white, and integrated teams in the early 1930s, as did the National Baseball Congress in Wichita.

Independent baseball wasn’t confined to small towns. Even large urban areas such as Chicago, Philadelphia, and New York, all of which hosted multiple major league teams, also supported thriving semipro scenes. Baseball was an unavoidable presence in everyday life: newspapers filled pages with box scores from games between business-sponsored teams, weekend amateur leagues, high school games, even company intramural leagues.

The best semipro teams reached a high level of competition, sometimes featuring current major leaguers playing in disguise or under pseudonyms. In 1918, Jeff Tesreau, one of the New York Giants’ best pitchers, abruptly quit to join the semipro ranks, arguing he could make more money playing ball outside the majors. Chicago White Sox pitcher Nixey Callahan quit midcareer to found a semipro team, the Logan Squares, which became an institution for decades afterward.

Urban white semipros are often overlooked, even by Negro League historians, but they formed a crucial part of the interracial milieu of black baseball and early twentieth-century popular entertainment. In the 1910s and 1920s, the Chicago American Giants often played the semipro clubs in the Chicago City League, which frequently featured current and former major leaguers. Black teams even occasionally competed in (and won) the City League. The American Giants’ games against the Logan Squares, Pyotts, West Ends, Gunthers, and other white semipro outfits were among their best-attended and most lucrative dates, leading the Chicago Defender to worry in 1919 that the team “depended on the other race altogether.”

This was the case throughout the urban North, where white semipros furnished stiff opposition — and good paydays — for Negro League teams. Jeff Tesreau’s Bears alone played at least 37 games against top African-American teams in 1921. The Bears shared a park, Dyckman’s Oval in Manhattan, with black clubs. According to Bo Campbell, who pitched for the Homestead Grays in the late 1930s, “The fact of it, if you take out East [for instance] where we was making our money, it was playing semipro white clubs. . . . That’s where the Negro leagues made most of their money, playing semipro whites. We’d draw good, good crowds.”

What kind of crowds? This is one of the most intriguing questions facing Negro League historians, because audiences often crossed racial lines. Crowds at all-black games were mostly African-American with a few white fans, at least according to much photographic evidence and a few references in the contemporary press. Most likely the racial composition of Negro League fandom varied from city to city. According to Donn Rogosin, games between black teams and the semipro Bushwicks at Brooklyn’s Dexter Park in the thirties drew “raucous, exuberant, gambling, integrated crowds of over ten thousand.” Decatur, Ala., native Doc Sykes, a pitcher in the 1910s and 1920s, remembered that Baltimore Black Sox games drew half white and half black crowds. On the other hand Billy Lewis, a sportswriter for The Indianapolis Freeman, an African-American weekly, estimated that when black/white games were played in Indianapolis, “from 1 to 2 percent of the audiences” was white. Lewis believed that in California and the west, the crowds were evenly divided between black and white.

The West Coast had been excluded from the white majors, although a strong minor league, the Pacific Coast League, flourished there, virtually independent until the 1950s. But the best baseball in California might well have been played from November to February. The California Winter League, based in the Los Angeles area, brought together teams of white major and minor leaguers semipros with one and sometimes two teams of African-American players. When white stars such as Ty Cobb or Tris Speaker took the field against their black counterparts such as Bullet Rogan or Biz Mackey, one could argue that southern California saw the best baseball played in the world at the time.

Up from the South

An oft overlooked aspect of the Negro Leagues is how deeply Southern the whole enterprise was. The white majors, it’s easy to forget, spent the first half of the twentieth century confined to ten cities in the northeastern quadrant of the United States, venturing no farther west than St. Louis and no farther south than Cincinnati. But the Negro Leagues included several Southern franchises, notably in Memphis and Birmingham, but also at times Atlanta, New Orleans, and Nashville, among other cities. The foremost black minor league was the Negro Southern League. Even more importantly, the Negro Leagues were largely a product of the Great Migration of Southern black labor to Northern industrial cities. The majority of Negro League ballplayers, 55 percent, were born in the South (of players born in the U.S., 69 percent were Southern), as were probably an equally large percentage of Northern fans. When the Birmingham Black Barons traveled to Chicago, they might be greeted by an “Alabama Day,” as all the local migrants from that state gathered to see their old team play.

In 1946, Eddie Klep, a white pitcher, joined the Cleveland Buckeyes of the Negro American League as the “reverse Jackie Robinson.” When the team played in the South, Klep wasn’t allowed to eat or stay with his teammates, and before a Negro League game in Birmingham, police not only barred Klep from the field, they wouldn’t let him sit in the blacks only section near the Buckeye dugout. The necessity for white sections in ballparks during Southern Negro League games testifies to a multiracial interest in the games. Yet, in much of the South, segregation laws kept black and white teams from competing on the field.

Unfortunately, deprived of the revenues generated by white/black matchups, the rosters of Southern teams, even the Birmingham Black Barons and Memphis Red Sox, were periodically plundered by Northern clubs, and the Negro Southern League remained mostly confined to developing young talent (although when the Depression killed off the Negro National League in 1932, the Negro Southern League stepped in to serve as an undisputed major league for one season).

From the 1900s through the early 1920s (at least), two posh resorts in Palm Beach, Fla., the Breakers and Royal Poinciana Hotels, each hired a team of the best African-American players to entertain the guests during February and March. The Florida Hotel League, as it was known, often imported whole teams from the North (the Brooklyn Royal Giants, Chicago American Giants, or Indianapolis ABCs, for instance). The games were very well-attended, by the overwhelmingly black staffs of the two hotels as well as the guests, and received lengthy writeups in the African-American press.

And Negro League spring training, which involved major Northern teams traveling through the whole region for as long as two months, wasn’t quite the preliminary, practice season we associate with the term “spring training” today — it was more like yet another extended barnstorming junket, treated almost as seriously as the “regular” season. So the South was truly the epicenter of Negro League baseball for at least three months a year (February through April).

The South produced such a prodigious amount of baseball talent in large part due to a thriving culture of amateur and semipro ball. Southern black colleges, such as Fiske University in Tennessee, Tuskegee University in Alabama, Wiley College and Prairie View A&M in Texas, and Morris Brown University in Atlanta, took baseball seriously. Industrial baseball teams proliferated in the South, especially in manufacturing centers like Atlanta, Nashville, and Birmingham. Teams were sponsored by mining companies, sawmills, and textile mills. Piper Davis, for instance, started his career playing for the American Cast Iron Pipe Company (Acipco) in Birmingham.

African-American semipro baseball was big enough in the South that plenty of good ballplayers stayed semipro rather than go with league teams. Pitcher Jeff “Bo” Campbell had major-league talent, but spent only a single year in the big time, with the Homestead Grays in 1937. Campbell spent most of his career playing instead for sawmill and paper mill teams in Louisiana, Texas, Arkansas, and Oklahoma. “You would always have a contract; they would pay your room and board, then about $15 a week,” Campbell told an interviewer. “Then you got other little gimmies, you know, like clothing and things like that at a reduced price. The temptation to go pro wasn’t that great.”

Baseball permeated Southern African-American life, down to the neighborhood level. Henry Kimbro, who enjoyed a lengthy career from the 1930s through the 1950s as a centerfielder and manager for such teams as the Baltimore Elite Giants, reminisced about his boyhood days: “Every part of Nashville had a park. We played sandlot. Every community had a team and we’d play from one park to another all day in the summertime.”

One state where Jim Crow was not always the rule on the field was Texas, where Mexican, Mexican- American, African-American, and white teams and players mixed and crossed the border freely. In 1930, according to Donn Rogosin, the Austin Black Senators barnstormed all the way to Mexico City. La Junta, a 1930s semipro team from Nuevo Laredo, Mexico, drew players from both sides of the border, barnstormed in Mexico and the United States as far as North Dakota, and competed on an equal level with Texas League teams. Many Negro League stars hailed from Texas and this more fluid racial setting, including Hall of Famers Cyclone Joe Williams, Bill Foster, and Rube Foster.

The (Inter) National Pastime

Black baseball — more than its white counterpart — crossed racial, national, and class boundaries; in Cuba, California, and black/white all-star exhibitions all over North America, the best athletes of all races brought before integrated crowds the highest caliber of baseball in the world, and the Negro Leaguers were at the center of attention. The phrase “national pastime” begins to seem parochial in this context.

Negro League baseball in general had an international face, due largely to the very forces that kept baseball segregated in the United States. African-American ballplayers, accustomed to ranging far and wide in their search for work, soon made their way to the popular and well-paying leagues of baseball-mad countries like Cuba, Mexico, the Dominican Republic, Nicaragua, Panama, and Venezuela.

Cuban baseball is nearly as old as U.S. baseball; the game was brought to Cuba by students returning from the United States, specifically the South, in the 1860s. According to the literary critic and historian of Cuban baseball Roberto Gonzalez Echevarria, the founders of the Habana Baseball Club, the first baseball club in Cuba, learned the game at Springhill College in Mobile, Ala. The Cuban game even preserved a very old version of baseball, with ten players on a side instead of nine, into the 1880s. The Cuban League was founded in 1878, only seven years after the first organized league in the United States. And, although nineteenth-century Cuban baseball appears to have been as racially exclusive as the U.S. majors, by 1900 the Cuban League had begun to integrate.

Soon after Afro-Cubans elbowed their way onto formerly all-white rosters, black players arrived from the United States. And at about the same time, Cuban players and teams began making their way to the United States, touring during the summer months (the off-season for Cuba’s winter league), and capitalizing on the connection between “Cubanness and baseball bolstered by the Cuban Giants and their imitators. Over the next few decades, all-Cuban teams became fixtures on the black baseball scene in the United States, even as Cuban League rosters regularly featured African-American players. C.I. Taylor and Rube Foster regularly brought their teams to Cuba.

Clearly the chance to escape the oppressive racial atmosphere of the United States powerfully attracted African-American players to Latin countries. The pitcher Max Manning described playing in Cuba like this: “You know how it is when the sun comes up after night? That’s pretty much what it was like. I’m saying in terms of being somebody, when you went to Latin America, you were somebody and you were treated as somebody and the newspapers treated you as somebody and the people treated you as somebody.”

The Mexican League imported more and more African-American players in the late thirties and forties. “Not only do I get more money playing here, [but] I am not faced with the racial problem,” said Hall of Fame shortstop (and Texan) Willie Wells about Mexico. “When I travel with Vera Cruz we live in the best hotels, we eat in the best restaurants and can go anyplace we care to. I’ve found freedom and democracy here.”

In the Dominican Republic, the U.S.-backed dictator, Rafael Trujillo, decided that owning a winning baseball team was a political necessity. So in 1937 he raided the roster of the Pittsburgh Crawfords for some of the most famous African-American ballplayers of the time, including Josh Gibson, Satchel Paige, and Cool Papa Bell. He kept tight control of his players. According to Paige, “If we went swimming, soldiers chaperoned us. We had soldiers on our hotel floors, too. Trujillo gave orders [that] anyone in town selling us whiskey would be shot.” Chet Brewer, a Negro League pitcher recruited by opponents of the regime, even claimed that Trujillo put his players in jail to keep them out of trouble (and in the country, presumably).

But most black experiences in Latin America weren’t that harrowing — in fact, quite the opposite. “It was just a marvelous experience and everywhere I went in Latin America it was the same thing,” said Manning. “One of the things I think that did drive the black ballplayers was that they all wanted to go through that window and get down there because everybody would come back talking about it, so you played harder in order to get there. You had a goal that you wanted to achieve: to get to Latin America.”

Reading the Hops

Those African-American men talented and hardworking enough to break into the Negro Leagues made for themselves a difficult, yet rewarding profession. In the white majors, owners controlled the labor market almost completely through a “reserve system,” whereby teams essentially owned players in perpetuity, unless they chose to trade or release them. The Negro Leagues, rather looser in structure, couldn’t enforce contracts for much longer than a season at a time. Teams raided one another’s rosters freely, even occasionally within the same league. Cross-border raids, by Mexican or Caribbean teams, were not uncommon. Consequently, black players were much more mobile and independent than their white counterparts. Hall of Fame shortstop John Henry Lloyd, a Palatka, Florida, native, put it succinctly: “Wherever the money was, that’s where I was.”

Negro Leaguers developed their own style of play shaped by slim resources, the barnstorming life, and endemic racism, resulting in a unique blend of self-reliance, self-discipline, improvisation, and teamwork. In the white majors, Babe Ruth’s emergence as the first modern slugger in 1920 marked the end of the “deadball” era and led to the dominance of home run hitters (which continues to this day). While Negro Leaguers hardly eschewed the home run, they did develop a game that relied on psychology, misdirection, and “inside baseball,” as opposed to the increasingly power-oriented major leagues. Herbert Barnhill, catcher for the Jacksonville Red Caps in the late thirties and early forties, put it this way: “Baseball is not like football. Football, it takes strength; but you play baseball trying to outsmart the other fellow.”

Players had to be versatile, because of small rosters (14 to 16, compared with 25 in the white majors). Everybody played multiple positions, and pitchers frequently also doubled at other positions. Small rosters also meant that substitutions had to be kept to a minimum. Pinch-hitting was usually limited to desperate, ninth-inning circumstances or injury. There were no relief pitchers, per se: all pitchers both started and relieved. Starting pitchers were expected to finish the game unless they were shelled or injured.

One of the players often acted as manager. Aside from Rube Foster and C.I. Taylor, bench managers were fairly rare on Negro League teams, though as the organized leagues became more prosperous in the 1940s they grew more common, with such men as Winfield Welch of the Birmingham Black Barons and Candy Jim Taylor of the Nashville Elite Giants (and many other teams) making careers as professional managers. Few Negro League teams could afford to hire coaches. As a result players had to rely on each other — and themselves — to make tactical decisions (whether to steal, how to pitch to a particular batter, when to bunt, when to replace a pitcher). “We practically had no coaching,” said Frank “Doc” Sykes, a spitball pitcher and native of Decatur, Ala. (see “From Spitballs to Scottsboro”). “What baseball you learned you picked up yourself, but if you were wise enough you could sit down on the bench and learn plenty of baseball right on the bench.”

As Piper Davis said: “Whites wasn’t calling it organized ball, but we had discipline. Your team would cuss you out for not bunting if the bunt was on; they’d embarrass you. You had to make the plays.” Still, there was a lot of room for individuality. “So many Negro ballplayers had their own style of doing things,” Davis remembered. “You might not think it was pretty, it wasn’t all alike.” In fact, Davis, who played in the white-dominated minors late in his career, thought that the intrusive coaching structure he found there hurt players by not teaching them to think for themselves.

Economics also made their mark on the game through poor and faulty equipment. “I had an old mask that would put wrinkles in my face ’cause it was so heavy,” said Barnhill. “Everything was so bad. The chest protector I had was so thin, when the ball hit me there I could feel blood running down inside me. Man, it was rough.” Andrew Porter told Brent Kelley, “Somebody hit the ball — a line drive back to you — and you try to stop it and it’d go through the webbing of your glove.”

Negro League teams couldn’t always afford top-notch grounds keeping, and in any case often played on bumpy, lopsided, and poorly-maintained fields. Teams were reluctant to call off games, so they sometimes played in driving rain. “We had to play in wet uniforms. We didn’t have a chance to dry them,” said Herbert Barnhill. “We didn’t have but one uniform.” Bad fields and bad equipment meant more errors in Negro League games than the white majors.

Baseballs could be expensive; thus they were kept in play even when discolored, battered, or cut, until they were gray, soggy masses. Kansas City Monarchs’ fan Milton Morris recalled, “If they knocked a ball into the stands, you got a ticket to come into a free game if you gave the ball back.”

Battered and overused baseballs tend to be less lively than brand new clean ones. It seems likely that, in general, the ball didn’t carry as far in the Negro Leagues as in the white majors, which in turn meant that strategies like bunting, the hit and run, and base-stealing were more attractive. Still, Negro Leaguers hit a fair number of home runs in the years after 1920. It could be that Negro League home runs were slightly inflated because balls that bounced once into the stands were counted as homers (ground-rule doubles under today’s rules). There may also have been, due to field conditions and wide-open base running, more inside-the-park home runs than in the majors. Despite the home runs, it seems clear from players’ testimonies and newspaper accounts that a “deadball” philosophy prevailed throughout the history of the Negro Leagues.

This meant an emphasis on “place hitting,” bat control, and sacrificing runners along. “I tried meeting the ball,” said Shreveport, La., native Willie Simms, an outfielder for the Kansas City Monarchs in the early forties. “Never no hard cuts, just try to meet the ball and get it in there.” As Piper Davis put it, “Our game was always ‘run and hit’, ‘run and bunt’.” Grant Johnson, a great, nearly-forgotten shortstop of the 1900s and 1910s, wrote a short essay on hitting in which he extolled bat control and patience, advising hitters to “seldom strike at the first ball pitched.”

Yet too much patience could backfire. Barnstorming teams had to adapt to prejudiced or biased local umpires. Newt Allen, longtime Kansas City Monarchs’ second baseman, described it this way: “The hometown umpire would call a strike way out here or way low if he thought you were a good hitter. Our owner told us that’s what was happening and not to be arguing about it. Just go up there and if it’s close enough to hit, hit it. And when you did find a pitcher who threw the ball right down the middle, he had less trouble getting us out than the tricky pitcher.”

Like Negro League hitters, pitchers relied less on power (blinding speed) than on guile, trick pitches, and control. “The three great principles of pitching,” wrote Rube Foster in 1906, “are good control, when to pitch certain balls, and where to pitch them.” Pitchers freely applied foreign substances to the ball. “See, nothing was outlawed in our league,” said player Bill Cash. “They’d throw spitballs, they’d throw cut balls, they’d throw the shineball, everything. But in the major leagues, they had to throw straight.”

Even one of the fastest pitchers in history, Satchel Paige, relied as much on control and disrupting hitters’ timing with hesitation pitches and other trick deliveries as on pure speed. According to another pitcher, Max Manning, “The phenomenon of Satchel was that Satchel had a miniscule curveball and a great fastball and was one of the best pinpoint control masters of all time. He could throw the ball anyplace he wanted to throw it anytime he wanted to throw it there.”

Negro League teams tried to pressure opponents and force mistakes through aggressive (though calculated) baserunning, or through identifying weaknesses in opponents and ruthlessly exploiting them. Rube Foster specialized in this sort of psychological strategy: on numerous occasions he had his team target a particularly weak opposing fielder, and bunt or hit constantly in his direction. Once, trailing late in a game, he ordered a steady diet of squeeze bunts, and the American Giants fought their way back from 10-0 and 18-9 deficits to tie it up, 18-18.

As one white sportswriter remarked about a Grays-Elites game in 1941: “There is one thing that distinguishes the National Negro League ball players from their major league brethren, and that is their whole-hearted enthusiasm, their genuine zest. They play baseball with a verve and flair lacking in the big leagues. They look like men who are getting a good deal of fun out of it but who want desperately to win. It was a relief to watch two teams as intently bent on winning as these two were yesterday.”

Leagues of Their Own

Black baseball teams played a vital role in fostering an interracial and international pastime, but they also played equally important roles in specifically African-American contexts, becoming focal points for civic pride, community life, and national cohesiveness. Local communities, along with the black weekly newspapers, were among the forces agitating for a national African-American baseball league, in place of the looser arrangements of independent baseball.

Northern African-American clubs profited from games with white semipros, but this relationship also had its costs. Both white and black owners ran African-American baseball teams; but for the most part, independent baseball in the North was controlled by white promoters and booking agents, preeminently in the teens and twenties a man named Nat Strong. It was explicitly to “keep Colored baseball from the control of whites” that Calvert, Tex., native Andrew “Rube” Foster, one of the best pitchers in the country in the 1900s, founded the Negro National League (NNL) in 1920.

The impulse to organize had a long history. After the turn of the century, series between top teams like the Philadelphia Giants and the Cuban X-Giants were beginning to be billed as “Colored World’s Championships,” and by the 1910s there were informal “western” and “eastern” championship honors (and sometimes “World Series” between regional champions). Several earlier attempts to organize national black leagues had failed, but Foster managed to bring together the most important figures in midwestern African-American baseball, including his bitter rival, C.I. Taylor, owner and manager of the Indianapolis ABCs; J.L. Wilkinson, white owner of the All Nations team, who brought the Kansas City Monarchs into the NNL; and Augustin “Tinti” Molina, who operated the western Cuban Stars (there was an eastern version, too), a team of Cuban players who toured the U.S. in the summer before returning home for the winter league season. Foster also included important teams in Detroit and St. Louis, and by 1923 had expanded to Memphis and Birmingham, among other cities.

In 1923, Ed Bolden, African-American owner of the Hilldales, collaborated with Nat Strong to create an eastern circuit, the Mutual Association of Eastern Colored Clubs, usually known as the Eastern Colored League (ECL), which raided Foster’s league for players. By the end of 1924, the two leagues had made an uneasy peace, and the first Black World Series was played between Hilldale and Kansas City. It turned out to be a classic. The Monarchs, led by the gutsy performance of its manager, Cuban pitching legend Jose Mendez, came from behind to win, five games to four.

Despite the artistic success of this first World Series, it was not a great success financially. The Black World Series would prove difficult to sustain, precisely because it was a series; most fans couldn’t afford to go to two or three games in a week’s time, so crowds tended to dwindle as the series progressed (the opposite of what should happen, ideally), and newspaper coverage declined accordingly. The World Series was played four times in the twenties, then lapsed when the ECL folded in midseason 1928.

Even in the best of times, the Negro Leagues walked on a knife’s edge economically. The majority of African Americans still lived in the South, but these communities were relatively impoverished and dispersed through rural areas. In the North, black populations were more affluent and more concentrated in cities, but comparatively small: Pittsburgh’s black population in the twenties has been estimated at about 80,000, Kansas City’s at 30,000. The pressures on Negro League owners were enormous. Rube Foster and Ed Bolden both suffered nervous breakdowns; Foster was eventually confined to an asylum, where he died in 1930.

The Depression finally destroyed Foster’s NNL in 1931. Many teams folded; others, like the Kansas City Monarchs, went on the road. It was gangster Gus Greenlee, operator of “numbers games” (illegal lotteries) in Pittsburgh, who rescued the organized Negro Leagues. Greenlee’s team, the Pittsburgh Crawfords, joined their crosstown rivals, the Homestead Grays, along with other, mostly eastern clubs in a new Negro National League in 1933. Greenlee’s NNL was followed in 1937 by a Negro American League in the west, built around the Kansas City Monarchs and Chicago American Giants, and including at various times Atlanta, Birmingham, Memphis, and New Orleans. By this time the numbers racket, as the most important source of black-controlled capital, dominated African-American professional baseball. Underworld figures such as Greenlee, Abe Manley of the Newark Eagles, Tom Wilson of the Nashville Elite Giants, and Alejandro Pompez of the New York Cubans fielded their teams as ways of achieving respectability and projecting an image of community leadership.

Greenlee and others put together the East-West All-Star Game, which became the national showcase for African-American baseball, and by 1947 attracted more than 50,000 fans, sometimes outdrawing the white All-Star Game.

25 Years Ago in Southern Exposure

“White ballplayers would have one expression and black ballplayers have another, but they talking about the same thing. Take a white ballplayer, he be keeping his eyes on the ball, but we be “reading the hops.” See? The black man was throwing the slider, but we didn’t call it a slider; called it a funky pitch, a horse-shit curve. . . . We didn’t have an expression about no slider.”

Lorenzo “Piper” Davis, interviewed by Theodore Rosengarten

Southern Exposure, Summer/Fall 1977

The 1930s Negro Leagues were on shakier footing than in the 1920s, playing shorter schedules, and more likely to lose players to Caribbean and Mexican teams, but World War II turned everything around. The Negro Leagues lost as many players to the military as the white majors, but many of the biggest stars (Gibson, Paige, Bell, etc.) were older, and mostly not subject to the draft. Meanwhile, for several reasons (the poor quality of the wartime white majors, a dearth of entertainment options, perhaps a greater sense of communal solidarity), larger and larger crowds gathered at Negro League games. The Negro World Series was reinstituted in 1942. By the time the Kansas City Monarchs signed a UCLA football star and war veteran named Jackie Robinson to play shortstop in 1945, things were finally looking up for the Negro Leagues.

Agitation for Integration

W.E.B. DuBois declared in 1903 that “the problem of the Twentieth Century is the problem of the color-line.” And as The Sporting Life said as early as 1891, “Probably in no other business in America is the color line so finely drawn as in baseball.” Still, after the disappearance of African Americans from white-dominated baseball in the 1890s (at about the same time that Plessy v. Ferguson legitimated the “separate but equal” doctrine), the color line kept getting blurred. White teams were constantly rumored to be interested in black players. In 1902, the famous manager of the New York Giants, John McGraw, brought an African-American second baseman, Charlie Grant, to spring training under the name “Chief Tokohoma,” claiming he was a “full-blooded Cherokee.” After Grant’s true identity became generally known, McGraw dropped him, though there was never an official edict against Grant’s presence. The major leagues, in fact, never adopted an explicit policy of exclusion toward African-American athletes, only a so-called “gentlemen’s agreement.”

Major league teams found another way around segregation by going outside the United States for relatively light-complexioned players of African ancestry. The Cincinnati Reds caused an uproar when they signed two Cuban outfielders in 1911, Rafael Almeida and Armando Marsans, although the team produced documentation of their European ancestry, and a sportswriter assured fans they were “two of the purest bars of Castilian soap ever floated to these shores.” Cuban infielder Ramon Herrera played in the Negro National League in 1920 and 1921, then in the white National League in 1925 and 1926, becoming, long before Jackie Robinson, the first Negro League veteran to play in the white majors (Marsans went in the opposite direction, playing in the Eastern Colored League in 1923 after his career in the white majors was over).

Many more Latin American players, mostly Cuban, trickled into the majors over the next few decades, especially after the Washington Senators hired a Cuban scout in the late thirties. There were always doubts about the Cubans’ racial identity, but foreignness and relatively light complexions cleared the way for some, though not for their darker-skinned countrymen. It was an open secret that many of these players did have African ancestry; the sportswriter Red Smith commented snidely that there must have been “a Senegambian somewhere in the Cuban batpile where Senatorial lumber is seasoned.”

Despite all the racially-mixed baseball played in Cuba and California, in black/white exhibitions and the great semipro tourneys, only one attempt was made during the Jim Crow era to create a truly integrated, nationwide, summer baseball league in the United States. The Continental League was the brainchild of Andy Lawson, who had collaborated with his brother Alfred (a former major and minor league pitcher) as baseball promoters and entrepreneurs. After sponsoring some international touring teams and founding a string of minor leagues, Lawson in 1921 put together a league with clubs in New York, Boston, Philadelphia, and other cities, and two innovations: a base on balls would put the batter on second base instead of first, and half the teams would be all-black, the other half all-white (one of the black teams, the Boston Pilgrims, would eventually hire some white players).

“[W]e have thrown down the bars to all American players without reference to color or race,” Lawson announced in the Chicago Defender, proclaiming that he was doing so in the interest of “true American sport.” Lawson recruited a black vice president, Jamaican-born Altamont James Stewart, a former hotel manager. “[W]e urge our people to give it their best support,” wrote the Defender. “The Continental League must be a success.”

Unfortunately it wasn’t. Though some of the clubs, notably Boston and Philadelphia, seem to have lasted through much of the season, playing the usual cast of opponents — semipro and college teams — little news of the league itself appeared, and it presumably expired sometime in midsummer, in almost complete obscurity. Andy Lawson dropped out of sight thereafter. His brother Alfred, who had founded a commercial airline that flopped at the same time as the Continental League, was more successful, eventually founding both a college and a utopian religion he called “Lawsonomy.”)

But increasingly, the idea of integration wasn’t left to marginal figures like Lawson. In the thirties and forties, more effective agitation against baseball’s color line would be provided by civil rights organizations such as the NAACP, African-American sportswriters such as Wendell Smith and Sam Lacy, politicians such as Mayor Fiorella LaGuardia of New York City, and by leftist activists. Lester Rodney, sportswriter for the Communist Daily Worker, commenced a campaign in 1936 to pressure the big leagues into admitting black players. Communists organized petition drives and tried to arrange tryouts for African-American players with white teams. World War II ultimately gave the integrationists a powerful rhetorical weapon: if black men could fight and die for their country, why couldn’t they play major league baseball?

But integration would not be achieved under Communist auspices, nor as a product of moral suasion or even political pressure. It would only happen when the white men who controlled major league baseball finally decided, for primarily economic reasons, that they wanted access to African-American athletes. Branch Rickey of the Brooklyn Dodgers made it abundantly clear when he proclaimed that “the greatest untapped reservoir of raw material in the history of the game is the black race.”

The historian Donn Rogosin points out that, whatever his hagiographers would later claim, Rickey’s motivations for integrating baseball were probably not primarily religious or moral. Before taking over the Dodgers, he had run the St. Louis Cardinals for decades without showing the least bit of interest in the rich tradition of black baseball in that city. According to Pittsburgh Courier sportswriter Wendell Smith, the stadium there, Sportsmen’s Park, was under Rickey’s regime “the only major league park to have a Jim Crow section.” Still, Jackie Robinson came to Rickey’s defense: “I have every reason to believe in Branch Rickey, and until he proves to me differently, I will always believe his reasons to be purely democratic in nature.”

Rumors of integration flew thick and fast through the waning years of World War II, and it was clear that the first club to sign black players might gain a huge advantage over other teams. According to a secret report commissioned by the major leagues in 1945, certain clubs earned fortunes by renting their stadiums to Negro League teams, notably the New York Yankees, who cleared $100,000 a year. But this kind of income was not equally distributed. The Yankees and Giants rented their stadiums, but Rickey’s Dodgers couldn’t, as there hadn’t been a major African-American team in Brooklyn for more than a decade. If the Dodgers signed black players, it might pull African-American crowds away from Negro League games in Yankee Stadium and the Giants’ Polo Grounds and into the Dodgers’ Ebbets Fields.

Negro Leagues player and manager Dave Malarcher argued it was no coincidence that integration was finally achieved just as the Negro Leagues’ success crested. Attendance was booming, the two leagues were thriving, and the East-West Game was beginning to outdraw the white All-Star Game. The majors allowed the color line to fall, Malarcher said, when they “saw those fifty thousand Negroes in the ball park. Branch Rickey had something else on his mind than a little black boy. He had those crowds.”

Baseball and the African-American Press

The early twentieth century saw the golden age of African American weekly newspapers — the Philadelphia Tribune, New York Age, Cleveland Gazette, St. Louis Argus, New York Amsterdam News, and Chicago Whip, among many others. The most important — Chicago Defender, Pittsburgh Courier, Indianapolis Freeman, Kansas City Call, Baltimore Afro-American — were distributed nationally. Several established “franchise” arrangements, publishing editions in many cities with the same national news, but local coverage tailored to the particular city. The sports pages might take up two (or more) pages out of 16 or 20, and baseball dominated the section, eclipsing boxing, college football, and semipro basketball.

Rowland Porter, a fan who lived in Montgomery, Ala., in the late 1930s, remembered getting the Pittsburgh Courier on lunch breaks from his job at a gas station. “There were a couple of big shade trees out back behind the gas station where I ate my lunch,” he said. “I’d sit down back there with whatever I was eating and turn to the Courier sports page. The Homestead Grays and the Pittsburgh Crawfords were the big national teams at the time, and they were both from Pittsburgh. So, I could keep up with them all through the summer.” Promoted by the weeklies, baseball in general, as well as specific teams, developed a nationwide following, and become one of the ways in which African American community was sustained on a national scale.

Beyond the Negro Leagues, the black weeklies reported extensively on all kinds of “marginal baseball”: white semi pros like Tesreau’s Bears and the House of David, women’s baseball teams like the Bloomer Girls, and teams of other ethnicities, such as a Japanese team from Waseda University that toured the United States in 1921. Meanwhile they largely ignored the white major leagues, and mainstream sports in general, unless they impinged directly on African-American or other marginalized sports.

At the Crossroads

The Negro Leagues, then, became as much an obstacle to Rickey-style integration as the racism of white players and fans. In an unfortunate echo of the 1857 Dred Scott decision (which held that “a black man has no rights a white man is bound to respect”), Rickey told Wendell Smith the Negro Leagues were nothing more than “a booking agents’ paradise. They are not leagues and have no right to expect organized baseball to respect them.” Rickey backed up his words with actions, steadfastly refusing even token payments to Negro League owners for players he signed away from them.

Robinson himself agreed with Rickey, penning a devastating attack on the Negro Leagues that appeared as the cover article in a 1948 issue of Ebony magazine. In “What’s Wrong with Negro Baseball,” Robinson criticized the players’ poor character and morals, as well as the low pay, exploitative owners, unruly fans, incompetent umpires, and overloaded schedule he’d had to contend with in the partial season he’d spent with the Monarchs in 1945. Due to lax rules, constant drunkenness, and a poor work ethic, he claimed, the quality of play in the Negro Leagues was quite low. His own success with the Dodgers, he hoped, “would make the fellows in the league I just left play harder, train harder, and give the fans much better baseball.”

In 1945 Rickey set up his own Negro League as a front for the scouting of Robinson and other African-American players (a team called the Brooklyn Brown Dodgers played in Ebbets Field for a season). In the view of Bill Veeck, later the owner of the St. Louis Browns, Cleveland Indians, and Chicago White Sox, Rickey really wanted to make his United States League work, thus cornering the black baseball market, and only when that failed did he decide to go the integration route.

Yet the Negro Leagues weren’t supposed to be obstacles to integration. Rube Foster had founded the NNL with what might seem like contradictory aims: to keep black baseball out of white clutches, and to nurture a baseball culture among black players that would prepare them for eventual integration. These two aims were reconciled by the expectation of Foster, and many others, that integration, when it occurred, would take the form most familiar to them: an all-black team (or teams) entering the white majors. Foster, Monarchs’ owner J.L. Wilkinson, and others harbored the ambition of organizing such a team, and a number of African-American ballplayers, including Satchel Paige, publicly supported this option over bringing individual black players into white leagues. It wasn’t just Negro League owners, either; Veeck had arranged the purchase of the Philadelphia Phillies in 1943, and planned to stock the team with Paige, Gibson, and other Negro League stars. When word of the scheme leaked out, the Phillies’ owners backed out of the deal, and sold the team to a much lower bidder.

Instead, black players would enter the majors one at a time. As the Negro Leagues began to lose stars, African-American fans deserted their teams in droves; Kansas City fans took the five-hour train ride to St. Louis to watch Jackie Robinson and the Dodgers — even when the Monarchs were in town. The Newark Eagles saw their attendance drop precipitously, from 120,000 in 1946 to 57,000 in 1947. After the 1948 season, the Negro National League folded, some teams joining the Negro American League, others joining the Southern Negro American Association or just giving up. In 1949, the Monarchs made the playoffs, but had lost so many players to the major leagues they had to forfeit the championship.

Yet Jackie Robinson, Larry Doby, Roy Campanella, and the other early black players to cross the color line didn’t smash the Jim Crow system at one blow. Nervous teams brought in African-American players very slowly, often in twos, to avoid forcing white players to room with them. Informal quotas kept many worthy Negro League veterans stuck in minor leagues they proceeded to dominate. Most historians agree that the New York Giants probably lost the 1950 pennant because they refused to call up future Hall of Famer Ray Dandridge to plug a gap at third base. Former Black Barons’ shortstop Artie Wilson, the last man to hit .400 in the Negro Leagues, only got 22 at bats for the Giants before he was sent down to make room for his former Birmingham teammate, Willie Mays. Piper Davis was buried in the Boston Red Sox system and never made it to the majors (the Red Sox wouldn’t bring up an African-American player until 1959).

By the mid-1950s, with the Negro Leagues shrunken to a four-team NAL, most of the barnstorming and semipro teams gone, and only a sprinkling of mostly young black players in the majors and minors, fewer African-American men made their living in baseball than at any time since the 1910s, possibly the 1890s. While black stars such as Mays, Hank Aaron, Don Newcombe, and Ernie Banks rose to the challenge, the African-American baseball presence was oddly top-heavy. “When they first come into organized ball,” commented Piper Davis, “all of them was stars that was playing. Wasn’t no black boys sitting on the bench.”

While the best African-American players found places in the integrated majors, a whole universe of Negro League coaches, managers, umpires, owners, and non-star players found themselves on the outside looking in. The majors didn’t hire any coaches from the Negro Leagues until Buck O’Neil, after years of experience managing the Monarchs, joined the Chicago Cubs in 1962. No Negro League manager ever managed in the major leagues; in fact, the first African-American manager wasn’t hired until 1975. What this disruption in continuity might have cost in terms of collective tradition, wisdom, and expertise lost, no one has ever attempted to measure.

Integration controlled by the white major league establishment for its own benefit also spelled disaster for high-quality baseball anywhere other than the Northeast and Midwest. The Birmingham Black Barons, led by Davis and Wilson, had won three Negro American League pennants in the 1940s; the South would not see anything close to that caliber of baseball again until the major leagues expanded to Houston in 1962. While New York City with its three big-league teams thrilled to the exploits of Robinson, Mays, Newcombe, Roy Campanella, and other former Negro Leaguers in the fifties, Birmingham, Memphis, and many other cities only saw rich black baseball traditions shrivel and vanish.

The destruction of the Negro Leagues reads like a precursor of the postwar devastation of historic black communities like the Hill District in Pittsburgh or the Hayti District in Durham, N.C., bisected and demolished by highway projects, impoverished by white flight into the suburbs and the depletion of urban tax bases. Buck O’Neil said the world the Negro Leagues made was “more or less, a black world, because . . . we kind of owned that world. We really did. But once we started with integration, I think it took a little something from us, as far as owning things.”

Legacies

The Negro American League played its last season in 1960. The Monarchs continued as a traveling team with no connection to Kansas City for several years thereafter. The Clowns lasted until 1973. In 1977, Hank Aaron, the last Negro Leaguer still playing professionally, retired.

Despite Rickey and Robinson’s disavowals, the most obvious legacy of the Negro Leagues is the death of segregation, in baseball and beyond it. However compromised the actual path of integration has been, the success of black-run institutions made Jim Crow untenable in the long run. As Foster had intended, the Negro Leagues honed the black game and produced the players (and men) who had the character as well as the skills to handle the tough task of integrating the white majors.

Negro Leaguers were pioneers in many other areas. Chappie Johnson might have been the first catcher to wear shinguards regularly. Willie Wells is said to have invented the batting helmet. The Monarchs pioneered night baseball in the early thirties, carrying a portable lighting system from town to town.

But for what has become a largely white baseball audience, remembering the Negro Leagues often plays itself out as a ritual of debating whether Negro Leaguers were the equals of their white contemporaries. While the overwhelming consensus of historians who study the matter is that the best black players were as good as the best whites of their day, that understanding doesn’t seem to have trickled down to fans, present-day players, the media, or even more mainstream baseball historians. When The Sporting News recently published a list of the 100 greatest players as chosen by a panel of experts, the list included 44 men who played primarily during the Jim Crow era: five blacks, and 39 whites. When Ted Williams, who himself played a key role in getting Negro Leaguers admitted to the Hall of Fame, named the twenty greatest hitters, 13 were pre-integration whites, none were primarily Negro Leaguers. And when Major League Baseball organized a fan vote for “The All Century Team,” 10 of 25 players named were pre-integration whites, but there were no African Americans from the same era.

Negro Leaguers in Japan

For decades, the standard story about the rise of professional baseball in Japan has credited a 1934 tour of Japan by major league all-stars, including Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig, for sparking interest in the sport and leading to the first professional league two years later. But the Japanese baseball historian Kazuo Sayama tells a different story. He argues that more credit should go to Negro League teams that toured Japan in 1927, 1932, and 1934 (the Philadelphia Royal Giants and the Kansas City Monarchs). The white players, he says, treated their opponents and the fans with contempt, running up scores against inexperienced opponents and insulting their hosts, both on the field and off. Ruth played first base holding a parasol. Gehrig wore rain boots. Al Simmons lay down in the outfield grass while a game was in progress.

The Negro Leaguers, by contrast, appreciated their hosts’ generosity, and enjoyed the respite from prejudice and discrimination. “The people were wonderful over there. I loved them, “ said the Monarchs’ Frank Duncan. “I hated to see them go to war. Wonderful people, the most wonderful people I’ve come in contact with.” In Sayama’s view, the Negro Leaguers’ courtesy, professionalism, and sincerity may have impressed Japanese fans more than the boorish and arrogant behavior of the white major leaguers.

Even more intriguing, though, are certain parallels between Japanese and Negro League baseball, including a shared emphasis on teamwork, finesse pitching, and the sacrifice bunt, which suggest even more substantial influence. Like Rube Foster, Japanese managers emphasize avoiding mistakes while pressuring opponents to make them, and seem to put great stock in scoring first to demoralize the other side.