From Spitballs to Scottsboro

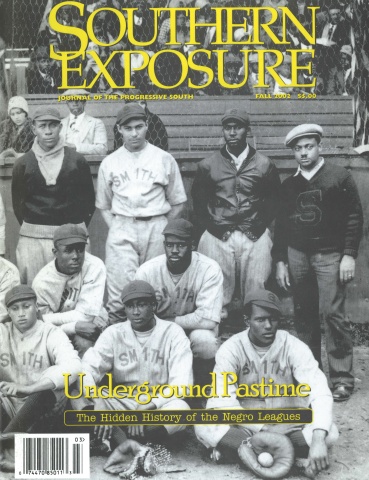

This article first appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 30 No. 3, "Underground Pastime: The Hidden History of the Negro Leagues." Find more from that issue here.

Frank “Doc” Sykes, the “pitching dentist,” was 90 years old when I met him at a Negro League reunion in Ashland, Ky., in 1982. Erect, white-haired, with a thin white mustache, he was the patriarch of the group.

In addition to baseball, I learned, Sykes played a critical role at a moment of great tension and danger in the history of the civil rights movement when he testified in the famous 1933 Scottsboro trial in Alabama.

Sykes and I met often at his Baltimore apartment, and I drove him to speak to members of the Society for American Baseball Research, an experience which delighted both him and them.

Mike Stahl of Baltimore and I spent many hours taping his memories and poring over newspaper files to reconstruct his playing record. The following is drawn from our interviews.

My parents were born slaves. There wasn’t much they could teach me other than truth and honesty and respect for elders. There wasn’t too much I could offer to my children other than what my parents had offered me.

I was born in 1892 in Decatur, Alabama, the town that the Scottsboro case put on the map. Decatur had 16,000 people and one auto — it went two blocks and broke down.

I was the seventh child of a family of 12; eight lived to be grown. My mother was part-lndian, I don’t know what tribe, Choctaw or what.

My father made money in a saloon. My favorite brother was a darn good businessman; he had a coal and wood business and an undertaking business. He died young, and my father took over his funeral business. They said, “You sold ’em liquor and got ’em ready for dying, and then you went on and buried ’em.” My father told us, “Get an education, I’ll help you.” He could do addition in his head better than I could with a pencil and paper. He’d say, “Figure that out again, son, that doesn’t sound right.” He was well thought of by everyone in Decatur. In fact, the day of his funeral the white businesses closed for an hour.

Frank followed his brothers as apprentices in the funeral home. Around 1906 at the age of 14, he remembered driving a wagon carrying coffins to the jail yard, where three black men were lined up on a triple scaffold. The trap door was sprung, and the bodies fell. One noose broke, and the condemned man jumped up, shouting, “Thank God, I’m free!” Instead, as Frank watched in horror, a new rope was quickly fetched and the execution consummated.

I came from a family of five boys. Three were exceptionally good ballplayers. My oldest brother I would consider tops; I don’t think he would have had a darn bit of trouble making the big leagues. And I followed him closely; I watched him and tried to act and do like he did.

In 1908 Frank enrolled in high school in Memphis.

When Jack Johnson knocked out Jim Jeffries, they announced it round-by-round at the Opera House. People said, “That black son of a bitch knocked Jeffries out!”

I went to Chicago around 1909, taking a course in embalming, and hooked up with a Sunday school league out there. I started out as an outfielder, and one Sunday the pitcher couldn’t get off, so the coach called on me to pitch. From then on I was the pitcher. If I have to say so myself, I was a damn good pitcher.

In 1912, I went to Morehouse College — it was called Atlanta Baptist College back then. I had pretty good speed as a pitcher: in one game I struck out 16 men and [still] lost the ball game.

I played against [famous Negro League pitcher] Dick Redding when he played with the Atlanta Depins, and I ran into him again when I went back there with the Morehouse team. His home was Atlanta, and Redding umpired a game for us against Morris Brown University. Redding called a couple of bad ones on us, but we beat Morris Brown anyway. I struck out only one man — and I tried to strike out only one man. They had a short dump over in left field. By this time I knew about what college boys would hit at. You threw it on the outside, they’d reach over and hit a little slow roller to the second baseman or the first baseman. The shortstop didn’t make a play in the field; the third baseman had one chance.

I entered Howard University in Washington in 1914 to study dentistry. A teacher of anatomy used to give us a lecture. He said, “Now you’ve come to Howard to get your medicine, your dentistry, your pharmacy. Plenty of women out there after you’re finished.”

I was a varsity player four years. The spitball was my best pitch because it had a sharp break away from a right-hand batter. I had excellent control of those spitballs; one game I threw nine straight spitball pitches, nine straight strikes. Sometimes I faked the spitball and threw a fastball that would shoot up. But I never threw at anyone’s head. I’ve thrown at their feet, though.

I didn’t put too much thought to playing professionally, knowing I was not going to make my living playing ball. I had made up my mind I was going to rely on dentistry.

The fellow who got me into big league baseball was a friend of mine and a student at the dental school at Howard, Bill Wiley. The school closed, and the baseball season opened up, and he had given the owners of the New York Lincoln Stars some insight into my abilities.

The McMahon brothers owned the Lincolns. They played at 136th Street and Fifth Avenue, a little park in there. I think my pay was $75 a month; I never did know what any of the other ballplayers got. I was working another job as a redcap at the Pennsylvania Station and at Grand Central Station — those were good-paying jobs. An old baseball player ended up being the head man at the Grand Central Station.

To my mind the Lincoln Stars were a real strong team. . . . It was managed by a fellow, Zach Pettus, a catcher. I haven’t seen any articles written about him, but he always managed a good team. I don’t know if you’ve ever heard of Pettus or not. He was born and raised in El Paso and could speak Spanish fluently. But the Spanish players didn’t know that, and we had a signal between us, so I always knew when they were going to steal.

Bojangles Robinson, the tap dancer, used to hang around the park. Had only one good eye. Pool sharks used to take advantage of him.

In 1915 Sykes pitched against Alert “Chief” Bender, a Hall of Famer then with Buffalo of the Federal League. Sykes won the game 4-3.

The next year the Lincolns went out west to play the Chicago American Giants and Indianapolis ABCs.

Rube Foster [of Chicago] was an outstanding coach. I was pitching the game, and they were getting a whole lot of infield hits. [Young] said, “You got a dumb shortstop. They been hitting slow ones to the shortstop and beating ’em out.” The shortstop on our team back then always played at the same place. Rube knew it, and they hit slow ones to him and beat them out.

Sykes lost the game.

I was a strikeout pitcher until I learned better. There was an easier way to beat teams than trying to throw it by them. The next Sunday I don’t think I threw one ball up there that would have broken a thick pane of glass. I lost 1-0 in 12 innings, but Rube Foster said, “Well, College, I see you’re learning some sense.”

I said, “Yes, Rube, I’ve learned that a slow ball is the best ball to use against colored teams, and if I can take off a little more [speed], I will.”

[In 1917] I went over to Hilldale to play for $125 a month. We played against semipro clubs around Philadelphia and Baltimore. I played with lots of good ballplayers that never made the big leagues, but I do think that if they’d been given the chance, they could have made it — Red Ryan, Phil Cockrell. And [the catcher] Biz Mackey, I loved to pitch to him.

Then I went to the Brooklyn Royal Giants. Dick Redding was manager. Once when we were playing up in Lebanon College, Pennsylvania, we dressed at the hotel there, and Redding and I were going to the park together. Dick was really black, and we met a white lady with a little boy. The little boy looked up and said, “Mother, mother, are those niggers?” Dick was a quiet, easy-going fellow, no trouble to anyone, but sad to state, he couldn’t read or write. I don’t know who made out his lineup card.

I practiced dentistry a little bit here in Baltimore before I finished school in 1918. Some fans thought Doc was my real name; they didn’t know I was a graduated dentist.

I used to come over to play with the Baltimore Black Sox on Sundays, starting maybe 1919, and stayed there six years. They were principally local talent, but before long they started bringing in men who developed into top ballplayers.

The Black Sox played in South Baltimore, and we were drawing bigger crowds on Sundays than Jack Dunn’s Baltimore Orioles [perhaps the greatest minor league team of all time]. I’d say anywhere from 2,500 up to maybe an average of 5-6,000 people. Almost half the crowd was whites. After 1937, when the Elite Giants represented Baltimore at Bugle Field, the white attendance dropped off tremendously.

We never heard much about black players in the white leagues. No, we never heard much talk of it. It was quite a different day. I guess back in those days we were treated so damn bad, why, we discovered it was a hopeless case. Never mentioned it.

After the 1926 season Sykes returned to Decatur with his wife and family.

I took the Alabama dental board examinations in some hotel, and I had to go up on the freight elevator, couldn’t go even one floor on the regular elevator, but there wasn’t a damn thing I could do about it.

In 1933 the sensational Scottsboro trial rocked the town when nine black teenagers, ages 13 to 19, were accused of raping two white women in a railroad boxcar. The boys were tried and eight of them sentenced to death within a week of their arrest [see “Scottsboro, Alabama”]. The appeal, which achieved celebrity nationwide, opened in an atmosphere of tension as National Guardsmen patrolled outside the courthouse.

The trial was held under Judge Horton, whom I knew personally. I had been in his court several times in murder cases, where one Negro shot another Negro. In one case I was asked to give an opinion as to whether a bullet could have been the cause of death. One of the lawyers objected, but Judge Horton said, “Your objection is overruled. Here is a man, graduated from Howard dental school and has a major in anatomy, and I feel he’s competent to say whether or not the bullet was the cause of death.”

Of Decatur’s 9,000 blacks, none had ever served on a jury. The defense called several prominent blacks — doctors, teachers, and others — to testify that they were qualified to serve. The prosecutor was described as “brusque” in his questions before an audience of whites, some with their feet on the bar rail, others spitting across the bar into spittoons placed there. Sykes, “a handsome man in a brush mustache,” according to the Birmingham News-Herald, was polite but “ostentatiously self-confident” in his replies. He produced a list of 200 local African Americans whom he said were competent to serve. Judge Horton agreed and ordered a retrial. However, the boys were convicted again.

As I’ve grown older, I think back on how the 12 men on the jury could bring in a verdict of guilty against nine innocent Negro boys. How could they — and I knew some of them on the jury — call themselves Christians? I suppose they didn’t think any more of a Negro than they did a dog.

Sykes helped two black reporters, spiriting them from house to house when “the situation became threatening for them.” When they ran into cars filled with Ku Klux Klansmen, they made a fast getaway.

After a cross was burned in front of my house, I thought it was a good time to come back to Baltimore.

Change I don’t think will ever come. If it does, it will be after we’re gone. A lot of people are fighting for that.

Tags

John Holway

John Holway is the author of many books on the Negro Leagues, including The Complete Book of the Negro Leagues, Black Diamonds, Voices from the Great Black Baseball Leagues, and Blackball Stars: Negro League Pioneers, winner of the Casey Award for best baseball book of 1988. This article is excerpted from an upcoming book, Blackball Tales. (2002)