Scottsboro, Alabama: Lost Political Art and the Recovery of a Radical Legacy

This article first appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 30 No. 3, "Underground Pastime: The Hidden History of the Negro Leagues." Find more from that issue here.

The following article contains references to sexual assault.

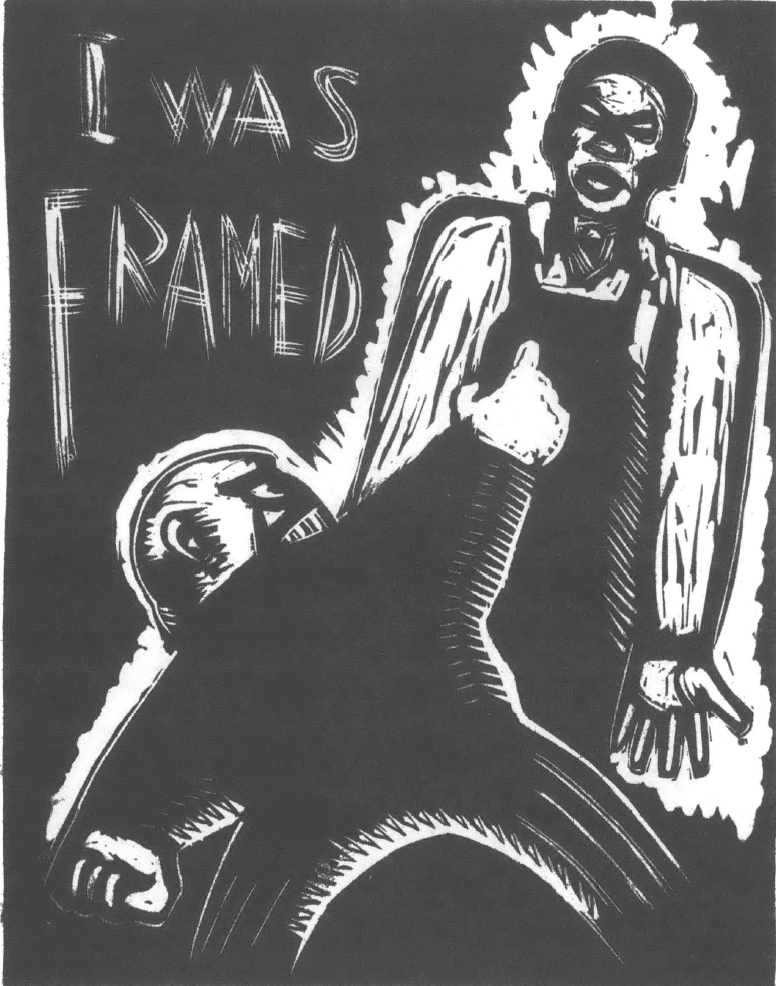

The case of nine young black men unjustly convicted of rape and sentenced to death in Alabama in 1931 sparked a worldwide campaign to free them, spearheaded by radical labor groups. One product of this campaign was a booklet of linoleum cuts illustrating the Scottsboro case and its context, printed in Seattle in 1935. We’ve reproduced several of these remarkable, evocative cuts on the following pages. Nothing is known about the artists, Tony Perez and Lin Shi Khan, or any other work they may have done. The only known copy of “Scottsboro Alabama” was recently discovered in the papers of Joseph North, editor of the 1930s journal The New Masses.

It began on a slow-moving freight train near Paint Rock, Alabama. Nine young men — Charlie Weems, Ozie Powell, Clarence Norris, Olen Montgomery, Willie Roberson, Haywood Patterson, Andy and Roy Wright, and Eugene Williams — were pulled off the train and arrested on March 25, 1931, for allegedly raping two white women. The women in question, Ruby Bates and Victoria Price, were also “riding the rails” or “hoboing,” as they used to say in those days. Although the nine youths did not know one another — indeed, they weren’t even in the same car at the time of their arrest — and most hadn’t even laid eyes on the two women, Bates and Price told the police that these black men “ravished” them (an old-fashioned word for rape). In one sense, Bates and Price felt they had little choice but to cry rape in order to keep themselves out of jail. Riding the rails was crime enough, but to be two single white “girls” traveling unescorted among “hoboes” could mean an added vagrancy charge or an arrest for prostitution.

Bates and Price’s troubles were nothing compared to those of the kids they accused. A few minutes before police pulled these folks off the train, a couple of the defendants had gotten into a tussle with some of the white men who, like them, were hopping freight cars in search of work. For a black man to strike a white man in the South was already a crime punishable by imprisonment, or worse. But when police discovered two young white women in the vicinity of these black men, the cry of rape was predictable, if not inevitable. It did not matter that most of the defendants were unaware of the women’s presence on the train. They were taken to nearby Scottsboro, Alabama, tried without adequate counsel, and hastily convicted on the flimsiest of evidence. All but thirteen-year-old Roy Wright were sentenced to death.

Stories like this one were not uncommon in the South during the late nineteenth century and throughout the first half of the twentieth. Black men were frequently accused of raping white women, and most never even made it to trial. “Judge Lynch” usually presided over these affairs; a local white mob would take custody of the accused (with the complicity of the local police) and save the state the costs of a trial by hanging the defendant from a sturdy tree branch or a street light or a bridge. Lynchings were more than hangings. They were public spectacles intended to punish and terrorize the entire black community. For whites who needed to prove their supremacy even as they struggled to make ends meet, a lynching was like a picnic, a celebration of their power and an affirmation of black inhumanity. Whole families often showed up — wives, children, grandparents — to watch black bodies tortured, burned, riddled with bullets, and to partake in the severing and selling of body parts. For the black people who had to clean up after this carnival of violence, a charred, mutilated body hanging from a tree served as a visible and potent reminder of the price of stepping out of line.

But these “strange fruit” hanging from Southern trees were not the only reminders of racial hierarchy. The fields, mines, and roads were dotted with black men on chain gangs whose main crime was insubordination. State executioners sometimes worked overtime to deal with the burgeoning number of black death-row inmates “fortunate” enough to escape the lynch mob for the electric chair. And then there were the cops: according to one study, during the 1920s approximately half of all black people who died at the hands of whites were murdered by the police.

The nine young men convicted of raping Ruby Bates and Victoria Price knew this history as well as anyone. Perhaps they didn’t know that over five thousand people were lynched in the United States between 1882 and 1946, but they knew their days were numbered. Or so they thought. What made an ordinary Southern tragedy into an extraordinary world historical event was the intervention of an interracial group of radicals called the International Labor Defense (ILD). Founded by the Communist Party USA in 1925 to defend what they called “class war prisoners,” the ILD set out to mobilize mass protest and to provide legal defense for working-class activists who they believed were being unjustly prosecuted for their political activity. The ILD was involved in the struggle to release Sacco and Vanzetti, two Italian immigrants with anarchist affiliations convicted of armed robbery and murder, despite a near complete lack of evidence. Though they succeeded in turning the Sacco and Vanzetti case into an international cause célèbre, they could not stop the execution. The ILD also defended trade union leaders Tom Mooney and Warren Billings, who were framed for a 1916 bombing in San Francisco. Their relentless campaign to free Mooney and Billings prompted a federal investigation that eventually led to their release.

The Scottsboro case differed significantly from the ILD’s previous cases. The defendants were not activists or trade union organizers; they were young black men from Tennessee desperately searching for work — hungry, anonymous, mostly illiterate. Boys and barely men, their ages ranged from thirteen to nineteen. When Communist organizers in Chattanooga and Birmingham had heard about the arrests, they visited the defendants in jail, gained their confidence and that of their parents, and initiated a legal and political campaign to win their freedom. As soon as the ILD stepped in, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), then the leading black civil rights organization, also sought to defend the “Scottsboro Boys,” embarrassed by their initial inattention to the case. As the two rival organizations fought each other for control of the case, the ILD’s lawyers succeeded in securing a new trial on appeal by arguing that the defendants were denied the right of counsel.

The mere fact that a little-known radical organization — whose Southern rank-and-file membership, by the way, was almost entirely African American — could succeed in halting the execution of nine impoverished black youths in the state of Alabama is itself remarkable. But this was just the beginning of a series of remarkable events. A month before the new Scottsboro trial opened on March 27, 1933, Ruby Bates confessed that she had lied: there was no rape. Yet, despite new evidence and a brilliant defense by the renowned criminal lawyer Samuel Leibowitz, the all-white jury still found the Scottsboro defendants guilty. Several months later, however, in an unprecedented decision, Alabama circuit judge James E. Horton overturned the March 1933 verdict and ordered a new trial. Horton’s bold decision cost him his judgeship, but it didn’t change much. A new trial was called and the presiding judge, William Callahan, practically instructed the jury to find the defendants guilty. Meanwhile, Leibowitz and the Communists parted company after an ILD attorney foolishly attempted to bribe Victoria Price. With the support of conservative black leaders, white liberals, and clergymen, Leibowitz founded the American Scottsboro Committee (ASC) in 1934.

A year later, after the Communist Party adopted the position that progressive forces all over the world need to build a “Popular Front” of radical and liberal organizations to fight fascism everywhere, they launched a tenuous alliance with the ASC, NAACP, and the American Civil Liberties Union. Calling themselves the “Scottsboro Defense Committee” (SDC), the group opted for a more legally oriented campaign in lieu of mass protest politics. After failing to win the defendants’ release in a 1936 trial, the SDC agreed to a strange plea bargain in 1937. Haywood Patterson, Andy Wright, Charlie Weems, and Clarence Norris were convicted, with Norris receiving the death penalty. The other three were given prison sentences ranging from seventy-five to ninety-five years. Ozie Powell pleaded guilty to assaulting a sheriff and was sentenced to twenty years. And as a result of back-door negotiating with Alabama liberals, the charges against the remaining defendants — Olen Montgomery, Willie Roberson, Eugene Williams, and Roy Wright — were dropped. One year later, Governor Bibb Graves commuted Norris’s sentence to life. Norris remained in prison longer than any other Scottsboro defendant; he was finally released in 1976.

The Scottsboro case became one of the key episodes in the history of race and civil rights in America. It wasn’t the legal maneuverings of the defense counsel or the actions of the defendants that invested this particular case with such historical importance. Rather, the ILD and their supporters brought this injustice before the world. Maintaining that a fair and impartial trial was impossible under white supremacy, the ILD publicized the case widely in order to expose Southern “justice” and pressure the Alabama legal system to free the nine defendants. Protests erupted throughout the country and as far away as Paris, Moscow, and South Africa, and the governor of Alabama was bombarded with telegrams, postcards, and letters demanding the immediate release of the Scottsboro Boys. The ILD’s involvement in the case, more than any other event, crystallized African American support for the Communists in the 1930s. And although the “Scottsboro Boys” themselves never identified with the Party’s goals, they became cultural symbols on the left — the subject of poems, songs, plays, and short stories that were published, circulated, and performed throughout the world.

One of those cultural products is Scottsboro Alabama, A Story Told in Linoleum Cuts, by two artists, Tony Perez and Lin Shi Khan. Its words and images not only tell the dramatic story of the Scottsboro nine, but also give us a sense of the context that made such an international campaign possible. Following the stock market crash of 1929, millions of Americans suddenly found themselves without jobs and living on donations from private and public charities. The unemployment rate for African Americans was much higher than that of whites — as much as 30 to 60 percent higher in 1931. In some major cities, the unemployment rate for black men was as high as 50 percent; among white men it hovered between 20 and 25 percent. But percentage differences offered no comfort to the jobless, irrespective of race. In 1932 a militant group of World War I veterans marched on Washington to demand assistance in the form of a government “bonus” for defending their country. Militant challenges also came from the Communist Party, whose members organized councils of the unemployed, fought landlords who tried to evict poor tenants, built radical trade unions, and took greater interest in defending “Negro rights.”

As early as 1929, it seemed as if a class war had broken out in the South. When striking white textile workers in Gastonia, North Carolina, faced down armed state troopers, their militancy surprised even the Communist organizers leading the strike. The Communists who were not run out of the state discovered an equally militant group of African-American workers near Charlotte, who boldly marched to protest the lynching of a black man named Willie McDaniels. Then, in 1931, on the other side of the black belt, about five hundred sharecroppers in England, Arkansas, rose up in rebellion to demand relief from landlords to enable them to survive the winter.

Much of this Southern class struggle took place within a few miles of Scottsboro. Black Communists in Birmingham, Alabama, began organizing demonstrations of the unemployed, which found themselves in violent confrontations with the police. On November 7, 1932, they attracted a crowd of about five thousand before the Jefferson County courthouse, to demand jobs and relief and freedom for the Scottsboro Boys. Battles broke out in the countryside as well.

In nearby Tallapoosa County, a group of black sharecroppers organized by the Communist Party formed a union and presented their demands to the landlords. In order to understand their demands, we must first understand sharecropping. Sharecroppers in the Southern cotton belt were essentially propertyless workers who were paid with a portion of the crops they raised. The landlord normally rented the “cropper” or tenant a plot of land, a shack to live in, draft animals, and planting materials, and he “advanced” the tenants food and cash during the winter months. These “furnishings” were then deducted from the sharecropper’s portion of the crop at an incredibly high interest rate. The system not only kept most tenants in debt, but it reproduced slave-like living conditions. Entire families were forced to live in poorly constructed one- or two-room shacks without running water or adequate sanitary facilities, and they survived on a diet of “fat back,” beans, molasses, and cornbread, which contributed to nutritional diseases such as pellagra and rickets.

To make matters worse, cotton farmers had been experiencing an economic crisis since the early 1920s. After World War I, cotton prices plummeted, forcing planters to reduce acreage despite a rising debt, and the boll weevil destroyed large stretches of the crop. Some landlords resorted to draconian measures, like refusing food and cash advances during the winter months.

The Alabama Share Croppers Union, led by brothers Tommy and Ralph Gray, Mack Coad, and a young schoolteacher named Estelle Milner, formulated seven basic demands, the most crucial being the continuation of food advances. The right of sharecroppers to market their own crops was also a critical issue because landlords usually gave their tenants the year’s lowest price for their cotton and held on to the bales until the price increased, thus denying the producer the full benefits of the crop. Union leaders also demanded written contracts with landlords, small gardens for resident wage hands, cash rather than wages in kind, a minimum wage of one dollar per day for picking and chopping cotton, and a three-hour midday rest for all laborers — all of which were to be applied equally, irrespective of race, age, or sex. Furthermore, they agitated for a nine-month school year for black children and free transportation to and from school. Finally, they made one demand that had little to do with their immediate circumstances: freedom for the Scottsboro Boys.

The union won a few isolated victories in its battle for the continuation of food advances, but most landlords just would not tolerate an organization of black tenant farmers and agricultural workers. On July 15, 1931, a police raid on a secret meeting at Camp Hill led to a shoot-out between police and union members. Ralph Gray was murdered, several men and women were injured, and in the aftermath nearly fifty people were arrested and at least four lynched.

Behind the violence in Tallapoosa County loomed the Scottsboro case. William G. Porter, secretary of the Montgomery branch of the NAACP, observed that white vigilantes in and around Camp Hill were “trying to get even for Scottsboro.” White mobs spread rumors throughout the county that armed bands of blacks were roaming the countryside searching for landlords to murder and white women to rape. Three days after the Camp Hill shoot-out, for example, the Birmingham Age-Herald carried a story headlined “Negro Reds Reported Advancing,” claiming that eight carloads of black Communists were on their way from Chattanooga to assist the Tallapoosa sharecroppers. In response, about 150 white men established a roadblock on the main highway north of the county only to meet a funeral procession from Sylacauga, Alabama, en route to a graveyard just north of Dadeville, the county seat. Despite the violence, the Share Croppers Union continued to grow. Its membership rose from eight hundred in 1931 to five thousand in 1933, reaching its height of twelve thousand in 1936.

Scottsboro, in other words, needs to be understood in the context of an unspoken war at home that rocked the Depression era, a war for racial and class justice, a war against starvation and second-class citizenship. For a moment, nine poor young black men and their mothers from the Deep South became celebrities, as did Ruby Bates, who, in another remarkable turn of events, went on tour for the ILD speaking on behalf of the Scottsboro defendants. But that moment in the sun set almost as fast as it rose. By the time the final defendants were released, the case had pretty much drifted into obscurity. Haywood Patterson and Clarence Norris produced autobiographies with the help of ghost writers, and Patterson died of cancer in 1952, two years after his Scottsboro Boy was published and four years after he had escaped from Kilby Prison. Norris, who published The Last Scottsboro Boy in 1979, lived the longest. However, despite his memoir and the press coverage surrounding his pardon from Alabama governor George Wallace, most people had forgotten about Scottsboro. At Norris’s funeral in 1989, only about one hundred people showed up — a fact lamented by the Rev. Calvin Butts in his eulogy: “This church might be packed. But after the immediate glitter of the case has passed and been tarnished by fifty years, who thinks about it again? This church might be packed, if connections can be made between the Scottsboro case and indignities today.”

Today we cannot afford to forget Scottsboro. There are still many “indignities” within the criminal justice system and many lessons to learn about the role of mass protest in bringing about justice. Moreover, Lin Shi Khan and Tony Perez’s work is more than a haunting, powerful collection of linoleum cuts; indeed, it’s more than a dramatic saga about the Scottsboro case. Khan and Perez have given us a sweeping context for understanding racial and class injustice. They begin their story not on an Alabama freight train as we did, but on the slave ships from Africa, in the antebellum cotton fields and the postbellum chain gangs, in the factories and prisons, in the courthouses and the streets where the battle for rights is a battle for survival. They read the story of Scottsboro on the bodies of working people, in their determined and bulging eyes, their broken necks, their manacled wrists, their raised fists. They give us a history in indelible ink so we are able to discover it a half century later, return it to our collective memory, and never forget the lessons it holds. And if we learn our lessons well, maybe we can follow their injunction and drive the villains of this tale “into the ash heap of the bitter past” once and for all.

Tags

Robin D.G. Kelley

Excerpted from Scottsboro, Alabama: A Story in Linoleum Cuts, by Lin Shi Khan and Tony Perez, edited by Andrew Lee with a foreword by Robin D.G. Kelley, New York University Press: New York, 2002. Robin D.G. Kelley is Professor of History at New York University. His books include Yo’ Mama’s Disfunktional! Fighting the Culture Wars in Urban America, and Race Rebels: Culture, Politics, and the Black Working Class. (2002)