"We Pay for Our Beatings": Life at the Citadel

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 30 No. 1/2, "Missiles and Magnolias: The South at War." Find more from that issue here.

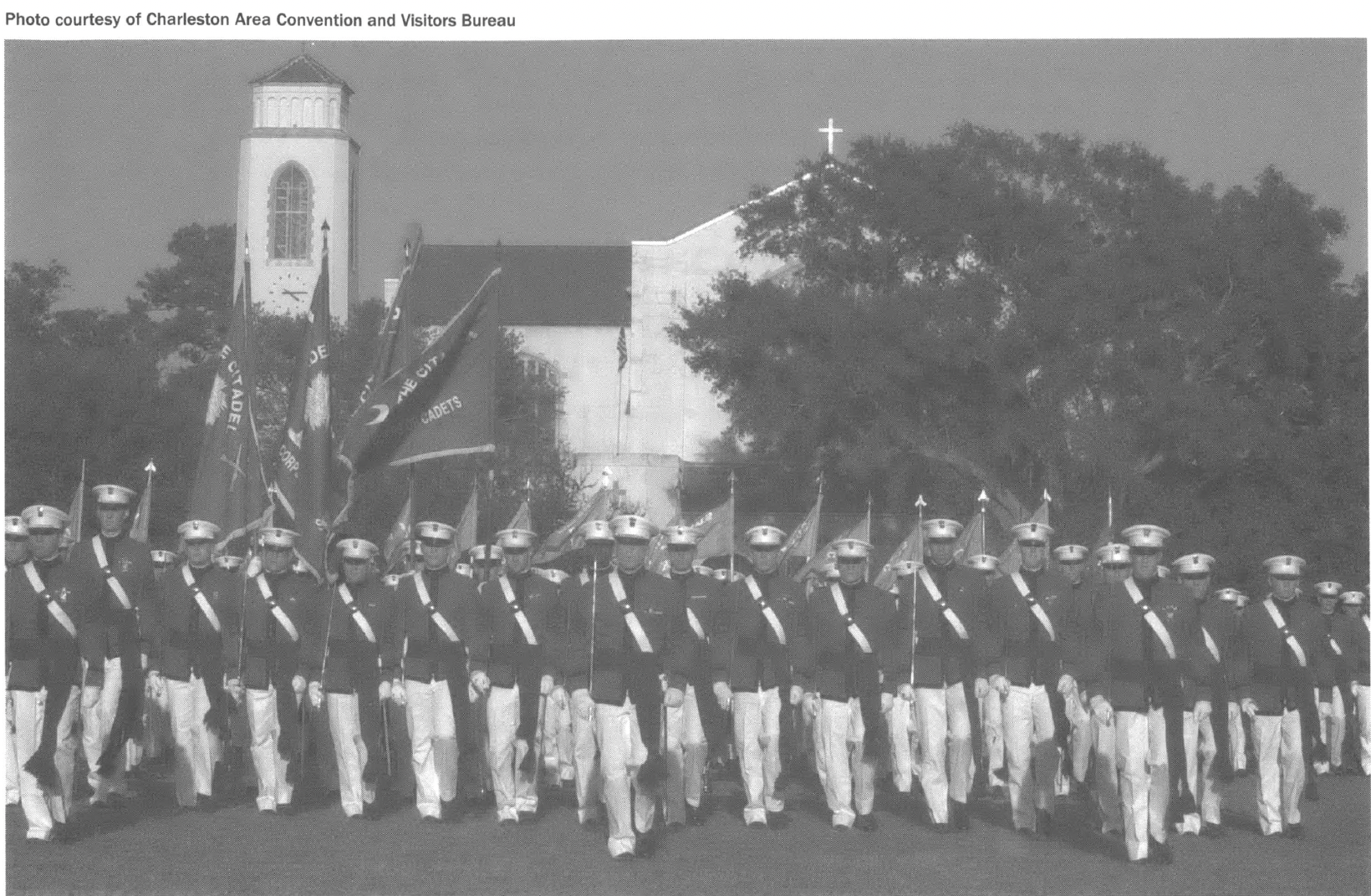

On most Fridays during the academic year, visitors to Charleston, South Carolina can swing by the Citadel to watch the cadets put on an impressive military spectacle. Tourists, parents and Charleston residents line up along the school’s central quad to watch the parade. They are surrounded by the bleached white towers that create the fortress-like architecture of the cadet barracks and the rusting tanks from battles fought long ago, as the cadets parade around the field in their regal Civil War-era uniforms, carrying their rifles, and accompanied by the school’s band.

The Citadel pitches the parades with the slogan “The best free show in Charleston!” That couldn’t be much closer to the truth. The parade is, after all, only a show. The cadets are undergraduate students who are not in the military (and over two-thirds never will be). Their guns are not loaded, and their elaborate, decorative uniforms are relics of a time far removed from today’s centralized and technologically-removed military.

But if there was ever a city fit for this curious anachronism of a school, it must be Charleston. The city that sells itself to tourists as a place “where the past is still present,” makes its point with horse-drawn carriages, costumed tour guides, and the maintenance of many a Southern tradition gone by the wayside in other parts of the region. It is no wonder, then, that while the rest of the world has stared in confusion at many of the strange “traditions” of South Carolina and the Citadel, Charleston has stood by them both proudly.

Beneath the veneer of static gentility that underlies the Citadel and Charleston, however, a roaring undercurrent of change has begun to break through the surface. These changes are prompted by a recognition that much of that aristocratic “tradition” has often come at the expense of the majority of South Carolina’s residents. South Carolina is not a monolithic state, and the version of the South represented in Charleston tour books is not a version most South Carolinians are familiar with. The surface issues of tradition and history and good ’ole Southern manners then, are not just a charade; they serve a function in the Southern imagination. It is for this reason that resistance to change has been so inexplicably fierce.

Shannon Faulkner’s 1993 acceptance to the Citadel is the most immediately recognizable of these changes and certainly one of the most important. The Citadel realized the symbolic significance of admitting a woman to the all-male school and dug in its heels for a legal battle that would eventually cost the school and the state of South Carolina over $7.6 million in legal fees in their effort to prevent Faulkner’s entrance to the public university. But school administrators weren’t the only people protesting the decision. The residents of Charleston went into high gear over the battle to keep women out of the Citadel, writing letters to the editor, urging the “outsider” media pouring into the city to stay out of their business, and plastering their cars with “Save the Males” bumper stickers.

A group of Charleston women known as the “Women in Support of the Citadel” even went so far as to dress up in hoop skirts and sit outside the school urging Faulkner to realize that she would be destroying a precious piece of Southern culture if she entered the school. The organization collected over 14,000 signatures from local residents who wanted the institution to remain all-male.

But the Citadel lost its court case, and over the years has gradually begun admitting women. The school now has 98 women, a small, but steadily rising 5.1 percent of the Citadel’s cadet population.

Two years later, the national media spotlight again turned on South Carolina as the battle began to rage over the fairly recent (1962) practice of flying the Confederate flag over the state capitol. In the midst of this struggle, the Confederate Heritage Trust discovered that the Citadel’s football stadium (initially built by and for the city of Charleston) was sitting atop the remains of several Confederate soldiers. The city’s preservation society asked administrators at the Citadel to allow them to excavate the remains in order to give these soldiers a proper burial.

On November 19, 1999, over 2,500 residents of Charleston — many of them dressed in black hoop skirts or Confederate uniforms — marched silently through Charleston to honor their fallen heroes in the Magnolia Cemetery. The immensely solemn funeral procession was held at the peak of the state’s controversy over the Confederate flag, which heated up with the NAACP and Gov. Jim Hodges squaring off against state legislators who were damned and determined not to lose this particular battle.

The funeral procession through Charleston, though ostensibly a simple, apolitical memorial service, was a loud statement about the unspoken racial politics of the white people of Charleston. Civil War issues are never completely devoid of politics in the South. That is particularly true in Charleston, where the first shots of the war were fired and where residents are more likely to refer to it as “the war of Northern aggression” than as the Civil War.

The flag did come down, and it was Citadel cadets — as requested by the legislative committee overseeing the matter — who lowered the Stars and Bars from the roof of the capitol for the last time.

Most recently, Charleston has been thrust into the national news with the controversy surrounding the prosecution of the Charleston Five. The politically ambitious Attorney General Charlie Condon hit a group of longshoremen (four out of five were black) with astoundingly trumped-up charges after the police sent to control the 150 union members prompted a scuffle that got out of hand. The transparent political ambitions of Condon, the clear anti-union sentiment motivating the arrests, and the undercurrent of Old South racial politics prompted an international response. Over 5,000 activists from across the state and many from places as far away as New York convened on the state capitol to protest the harsh punishment of the longshoremen. The overwhelming response to the case was apparently more than Condon had anticipated, and last October he removed himself from the case. The Charleston Five quickly plead no contest to a misdemeanor charge and were immediately released from their house arrest.

The swift and coordinated response to the Charleston Five has demonstrated that there is significant organizing potential within South Carolina and the South in general. But the image of Old South traditions has seeped into the nation’s consciousness. Becci Robbins, an organizer with the South Carolina Progressive Network, the group that helped coordinate the Charleston Five response, says that image stalls organizing in the region. Robbins says it is more difficult to get money and support from national organizations that see the South as a sure-fire loss each time around.

Robbins does believe, however, that the massive response to the Charleston Five, while it wasn’t able to change decades-old assumptions about the region, did go “a long way toward energizing the labor movement in the South” — certainly words of encouragement for progressive activists around the region.

Yet the anachronistic pieces of the state’s past continue to hold immense symbolic power for many residents and leaders of the state, a power represented in its extreme in the case of the Citadel and the controversy over the Confederate flag. In both cases, the parties defending the Old South traditions were willing to sacrifice large amounts of money (in legal fees for the Citadel and in tourism dollars for the state) to defend what they saw as a dying cause. Both of these cases are notable not only because they eventually resulted in change, but also because so many people became so emotionally and intensely invested in preventing that inevitable change.

It’s clear that history (at least some versions of it) is fiercely protected in the state of South Carolina, and that is nowhere more obvious than in Charleston, the city that perhaps best exemplifies the plantation myth that still survives in the thinking of many a Southerner. The gigantic, pastel-colored waterfront mansions that line South Battery and all the rest of the narrow, cobbled streets of downtown Charleston perfectly embody the noble wealth of a South that exists more in the imagination than in reality. Even though there are many people in Charleston who do indeed still hold debutante balls, send their children to formal cotillions and own those palatial mansions, Charleston as a whole is terribly poor. It is, per capita, the 24th poorest county in the nation.

All the genteel charm that draws tourists to those horse-drawn carriage rides around Battery Park is — like the “military” cadets at the Citadel — much more show than substance. Charleston has a lot at stake in protecting that image: over 3.9 million tourists contributed approximately $1,000 each, pumping nearly $4 billion into the local economy last year alone. But the melodramatic responses to the admittance to women at the Citadel and the lowering of the Confederate flag all seem to indicate that there’s more at work here than simple financial calculus. A quick look at the largest local employers might point to an answer.

The second and third largest employers in the city are not the Citadel or Fort Sumter, or even those horse-drawn carriage tour companies. The U.S. Navy and Air Force rank second and third respectively, employing together over 11,000 full-time employees in the Charleston metropolitan area. More than the 8,000 individuals are employed by the city’s largest employer, the Medical University of South Carolina. Charleston and South Carolina, like much of the South, are dependent upon the financial purse strings of the United States government and multinational corporations for their economic survival. South Carolina is notorious for its desperate attempts to entice outside — often international — industry to the state.

Many of these deals have resulted in such outrageous bargains for the corporations that the localities receive little to no tax money while the workers so gratefully employed within the state’s lagging economy are paid pitiful wages because of the state’s fierce right-to-work laws, which continue to grow fiercer each year. South Carolina is the 10th poorest state in the nation, but it is not alone. Eight of those top 10 states are located within the South and many of them have an economic profile strikingly similar to that of South Carolina: right-to-work laws that prevent unionization of workers and keep wages low, weak environmental laws that protect corporations at the expense of local residents, and lower levels of educational attainment than the nation’s average.

It is no wonder, then, that South Carolinians hold desperately to the traditions that distinguish them from the rest of the nation and that they feel bring a sense of aristocracy and self-importance to a region badly beaten by our changing global economy. Seventy-six percent of cadets at the Citadel are from the South and many view it as a uniquely Southern and tradition-rich institution.

The Citadel is still intimately linked to its Civil War past. All knobs (first-year cadets) are required to memorize the battles fought by the Citadel regiment in the Civil War. “Dixie” was sung at each football game as recently as 1998, when the administration finally put that tradition to bed. Its location in Charleston also reinforces this immediacy of the past for the cadets. Tour buses drive through campus each day with people as interested in the history of the Citadel as in the downtown Slave Market, where a man dressed in colonial garb still tolls a bell at passersby.

But it might be less the costumes or battle hymns than that notorious hazing process that makes the Citadel most clearly a Southern institution. Brent Meyers, a third-year cadet from Jacksonville, Florida, says that “tragedy and hardship” are unifying forces between cadets. The brutal life of first-year knobs and the camaraderie that results are what define the Citadel experience for Myers: “That for me is the Citadel. They put you through nine months of hell that forms an amazing bond.”

C. Vann Woodward, the well-respected Southern historian, understood Southern identity to be rooted largely in the experiences of defeat and poverty that are so foreign to much of the rest of the American experience. The desire to suffer through a tortuous period of hazing in order to be remade into a “Southern gentleman” is not then unlike the South’s readiness to hand over basics like environmental protection or taxes in return for low-wage jobs that foster an illusion of economic independence, while granting ever more control over the Southern economy.

The show of military might in the Citadel — a school completely unaffiliated with the military, aside from its ROTC program — is intimately linked to the costumed tour guides in downtown Charleston that parade visitors through the slave market-turned-shopping plaza while most residents of the state gaze from afar at the stately mansions that dominate the city’s landscape. Both are merely performances, but performances that carry an awful weight in this poverty-stricken state burdened with aristocratic Southern tradition.

When Meyers discusses the relationship between the Citadel and the much more elite United States Military academies, he says that everyone at the Citadel hates the cadets from the academies because “they think they’re the greatest thing to happen to the military.” The academies lack the harsh militarism of the Citadel or the Virginia Military Institute and instead focus on academic classes designed for service in the military.

He goes on to tell a joke about the relationship between South Carolina’s Citadel and the United States Military academies, pointing out that the cadets at the academies are paid to attend and are constantly reassured of their importance to the future of the military, without suffering through the harsh environment at the Citadel.

“But here at the Citadel,” Meyers says, “we pay for our beatings,” an observation not far removed from the economic life of the South.

Tags

Jenny Stepp

Jenny Stepp is a recent graduate of the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. (2002)