This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 30 No. 1/2, "Missiles and Magnolias: The South at War." Find more from that issue here.

I never actually saw any tigers in the Tiger Mountains. We walked into them, though — the mountains, not the tigers — from an eight-day stay at an eight-cubicle whorehouse on Loh Du Beach, where one of the prostitutes called herself Pussycat.

A few days into our sojourn in the Tigers, we got word that November Rangers, our Long Range Reconnaissance guys, had just hit a North Vietnamese Army (NVA) hospital. We had to secure it for a damage assessment.

The Landing Zone was an artillery crater on the side of a mountain, and the choppers hovered over 10 feet off the ground. When I leaped out, I hit the ground and tumbled into a heap with around 60 pounds of rucksack and radio pinning my head against the mud and shredded vegetation. To my credit, I never let go of my weapon.

We’d all taken a few hits off the “DXs,” Kool cigarettes with some heroin sprinkled into them, before the helicopter “assault,” so I didn’t really feel the latest knots on my head, and I was able to walk off the funny sensation in my ankle.

When the November Rangers had pulled back, a CH-47 Chinook came in with a sling load of thickened fuel called Phugas. It was released in a wide pattern over the target, then ignited by a spotter plane with a little rocket. . . .

It seems like that’s what happened, anyway, but to be honest my memories have bunched up. . . . The whole place was on fire when we got there. I remember that much.

Some of the guys from First Squad linked up with us. I was in Second. They told us they’d found the bodies of four NVA nurses.

Since it was an NVA “hospital,” then the women there had to be NVA “nurses,” right?

They’d been lined up in a row, all on their backs, and they were pretty burnt from the Phugas, but the First Squad guys had scoped them out up close. Lined up on their backs, side by side, all of the bodies had sharpened sticks thrust into their vaginas, and each had a bullet hole in her head. There was a little laughter. “Fuckin’ rangers.”

I laughed a little, too. The most dangerous thing I might be was a pussy or a gook lover. Laughter was armor. Inside that armor, like when I first got in country and watched members of my platoon go into the ville to murder an old woman hoeing her potato patch, my spirit divided like a cell . . . again.

Male to Alpha Male, I had arrived. On the rack. Between the tight-lipped morality of my upbringing and the savagery — now making itself known — that I had inherited with my scrotum. Boy to Man, Male to Alpha Male.

Warrior. Not the Homeric ideal warrior-hero. We laughed at that shit! Our work was wet work. Nasty work. Smoke a DX after.

I was nineteen. I was afraid. So I laughed.

Memory is a funny thing. Like when my dad died, and that was only 10 years ago, and the grief cascaded out of me seeing him there in the box with his funny hat on (a family sense of humor) and not moving. We closed the lid, loaded him into a car, and buried him in a rocky little oak stand outside of Hot Springs.

I remember vaguely that when I was very young every sentient being I encountered was someone I loved. Step by step, being by being, parents and relatives and strangers and associates and the black and white television in our living room all taught me to stop loving. I didn’t stop, but they crippled my capacity for love. They made me strong. My sister was encouraged in her loving. But once she started to grow tits, she was encouraged to stop thinking.

I wonder, if I had a choice now to go back and start over, would I choose to live with thinking distorted by crippled loving, or loving distorted by crippled thinking?

My father taught me to fish when I was very young, and he brought home the corpses of animals from hunting. He taught me to clean them, the fish and the quail and the rabbits and an occasional deer. I learned to cut into their bodies and remove their skins and eviscerate them. My father picked me up and hugged me for my performance. I learned that I could win approval by stepping over my reticence and fear and loathing. The truth is, too, that this cutting was a thrilling, sensual thing.

I was a loving boy who delighted in the flight of quail, a loving boy who delighted in the approval of his father, and a sensual boy who could cut into reality. They stood against each other, but not equally. And I ate the fish and the rabbit and the quail and the deer.

I don’t really remember the original boy. I just have the memory, so that’s all I can grieve for now and I don’t remember really deep grief, so the grieving is removed from itself. I didn’t know it at the time, but I was being shaped for a career in the Army.

I was very small for my age as I grew up, and I remain a fairly diminutive person today — perhaps a bit less diminutive around my midsection, but still never a very imposing physical presence. In the world of boys becoming men, this can be a terrible liability and the source of a paralyzing fear.

One day in junior high school, where I was the smallest person, male or female, our science class had recruited a volunteer — me — to have his finger lanced with a sterile medical lancette for a drop of blood on a microscope slide. I had the girls’ attention because the bigger boys had emphatically refused, and I swelled inside at my little victory over them.

Later in the cafeteria, after stealing several of the lancettes, I sat down and ate lunch. Then, I pulled out the lancettes, opened one, and systematically lanced all 10 of my fingertips, nursing a drop of blood from each one. Several people paled, and some of the biggest, most aggressive boys in school — boys who had entertained themselves by closing me in my gym locker — gave me a look of pure terror. I had cut into my own body. I began to understand the psychology of power and transgression. They never locked me in that locker again.

A friend recently asked me if I had ever been diagnosed with post traumatic stress disorder. I haven’t, but I picked up a book about trauma after she asked the question. Here’s what it said: trauma destroys our fundamental assumptions about the safety of the world; trauma destroys the positive value of the self; trauma destroys the belief in a meaningful order of creation.

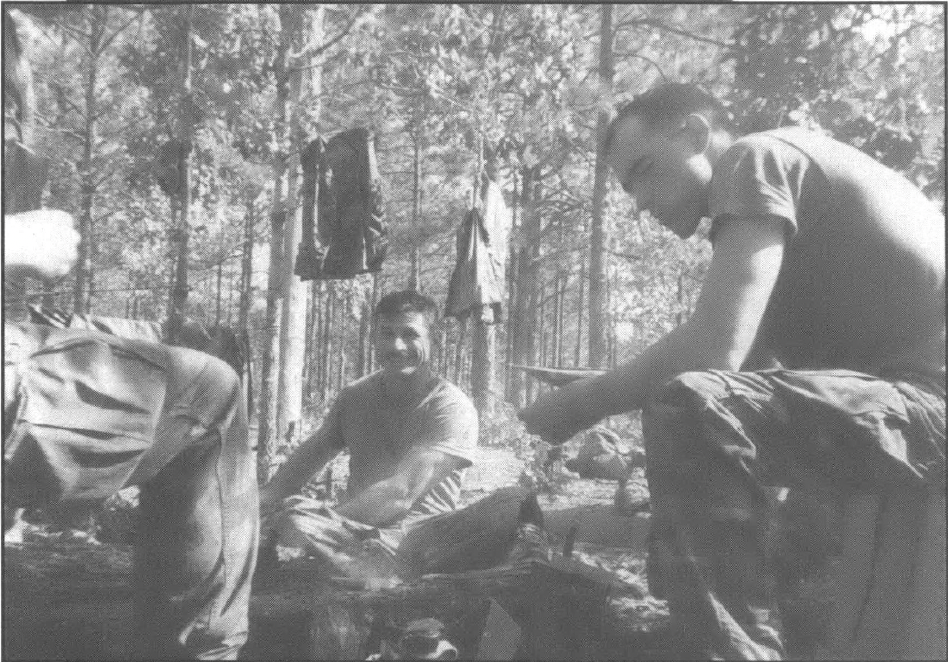

But the Army sent me to a kind of two-decade school, and in “school” I learned some things.

The world is not fundamentally safe.

The first time I felt like I was universally validated was when I joined the Army. People couldn’t stop praising me, even after I’d burned down folks’ homes, even after I became an accomplice in a mass murder.

I’ve heard the bullshit stories about the poor spat-on Vietnam vets, but no one ever spit on me when I got back from Vietnam. They didn’t spit on me when I came back from other exotic places either: El Salvador, Guatemala, Grenada, Colombia, Peru, Somalia, Haiti . . . I got a chest full of ribbons like fruit salad on my Class-A uniform, and people just admired the hell out of me. In exchange for my “trauma,” I was awarded a very high value for my “self.”

And there is no meaningful order in creation. Trauma or no trauma, look as hard as you want, and you have to lie to make it happen. There is plenty that is gratuitous.

A lot of the brown people I ran into, in the process of securing Uncle Sam’s favorable investment climates around the world, never had any assumptions about the safety of the world. Moreover, I can drive fifteen minutes from where I’m writing right now and find people who can’t assume safety. So is the world suffering from post traumatic stress disorder, and if it is, what is its meaning? Who is responsible?

Even those who purport to heal us don’t understand. It don’t mean nuthin’, we used to say. What? Nuthin.’

People think we’re all damaged. A lot of that’s hype. A lot of it is veterans who never saw combat cashing in on the tragic pose they can cop with the credulous war-worshipping public. But those of us who did see combat, we are really just the healthiest people in the whole society, at least by some standards. No patience for hypocrisy. We understand why the guy in All Quiet on the Western Front goes back to the front. Shit is real there; honest. Some of us can be what you wanted us to be, men, but not like you wanted us to be, liars.

The military boosters would hesitate to tell you how homoerotic the whole thing is, because they are still bent on the instrumental project of de-feminizing their boys so they’ll be good workers, good husbands, good fathers. Good soldiers. Men, good men.

Get with your significant other sometime and do something that cheats death. Jump out of an airplane. Get into a fight with firearms. That luminous feeling lasts for hours. It’s like an orgy, like entering a haunted house, like murder, like giving up your religion.

Transgression.

Then it’s just a question of whether you refuse to see or not. I started to see something.

I saw people who were supposed to be my enemies who practiced transgression. But they didn’t do it out of fear, like me. They did it because there were no options left open to them. They did it because their families had been burned out or murdered or had sharpened stakes driven into their vaginas. They did it so a next generation might not have to live under someone’s heel. They did it out of hate, because they did it out of love. Some were older than soldiers, and some were younger than soldiers, and some were women.

They fought not to dominate but to defend and liberate. We rotated back to the States, where we could nurse out post-trauma disorders, but they were there for the duration.

I don’t know how to explain this because the voices in me, after 50 years, two marriages, five continents, and more than two decades in a uniform are as numerous as they are contradictory. And I was so slow to learn, lost in the fog of my phallicentric, shattered little world. The veterans.

Former U.S. Senator Bob Kerrey of Nebraska ordered the execution of 15 Vietnamese children, women and old men in 1969. Do we remember how fast that story popped up last year, then disappeared?

He’s a liar. That lame story that the victims were caught in the crossfire! He’s a liar. But everyone hushed right up on that one, because his fly was open, and his dick was showing, and we do so cherish our denials.

Fifteen people don’t get killed outright in the crossfire of a single, short, small-scale firefight. The odds against it are astronomical. And it was night.

On April 23, 1971, as a member of Vietnam Veterans Against the War, future Massachusetts Senator John Kerry, whose name and background are so similar to Kerrey’s that it had me confused for a day about the Kerrey story, testified to the U.S. Senate that U.S. troops he knew “had personally raped, cut off ears, cut off heads, taped wires from portable telephones to human genitals and turned up the power, cut off limbs, blown up bodies, randomly shot at civilians, razed villages in fashion reminiscent of Genghis Khan, shot cattle and dogs for fun, poisoned food stocks, and generally ravaged the countryside,” and that “these were not isolated incidents but crimes committed on a day-to-day basis with the full awareness of officers at all levels of command.”

He’d get it if I told him about the Tiger Mountains.

Thirty years later, Senator Kerry has been mainstreamed. He supports the sanctions on Iraq, and has been a vocal cheerleader for the bombing of Yugoslavia, the attacks on Afghanistan, Iraq, et al. This is a testimony to “compromise and reform,” the lexicon of opportunism. He set aside his hate and his love for a career. What a man!

Bob Kerrey is a liar today, but I can assure you that John Kerry told the truth on April 23, 1971.

I was a machine gunner with the 173rd Airborne Brigade in a mountain range we called the Suikai on that day. All that he was describing to the comfortable white men of the U.S. Senate was still taking place in Vietnam at the very moment of his description. Months earlier, in the Tiger Mountains, the November Rangers “took out the NVA hospital” and the nurses were shot in the head and had stakes driven into their vaginas, who knows in what order.

Bob Kerrey says he is ashamed. Maybe.

I don’t think our shame is enough. Do you?

Military people, especially that minority who have actually been combatants (and know that in the end we are all combatants), who take that first baby step of comprehending the poisonous lies of the American military fetish, the most important transgression of all, have a duty to go beyond mere shame.

We must witness. And we must interpret, with all our pathologies, and all our voices.

Kerrey’s foray into the Mekong, the My Lai massacre, No Gun Ri in Korea, the current slow-boil murder of Iraqi people, the violation of Yugoslav sovereignty, and the financing and advisement of the bloodthirsty Colombian Army and their drug-trafficking paramilitary allies: these are not, in John Kerry’s words, “isolated incidents but crimes committed on a day-to-day basis with the full awareness of officers (and political officials) at all levels of command.” The truth has ever been the same. The cover stories have ever been the same. The job of penitent veterans must be to assault the denial that these cover stories market to the public consciousness and conscience.

This is the transgression that can begin to redeem us, the way to grace from our wretchedness as soldiers, as imperialists, and as men. If we want meaning, we better make it.

Even as many of our own people go without, we have acquiesced to a government in the thrall of corporate money and power that wants to appropriate $350 billion a year for what is euphemistically called “defense.” The U.S. military establishment is a monstrous thing, put to monstrous purposes, and we who were the instruments of that establishment — if we are to reclaim our own humanity — must come forward and help Americans understand what is done in their name.

Especially Southerners, because we are still trapped in the deadly headlights at the race-sex-death intersection. We must be the blasphemers, because that gives others permission to confront the orthodoxy of reverence before “warriors.” What were the lynching parties and the rapes of black women but rites of masculinity and war? What did they serve but systemic power?

Our children who go, as I did, into the armed services, are being made tools — or worse — for an institution whose sole purpose is to employ violence against those who threaten the dominance of those who are dominant, and against those who would tell the submissive that they need not submit.

We often worry about sending our children to die, but we should also worry about sending our children to kill. To do that, we will have to encourage them to love, and not to fear.

Mea culpa. Mea culpa.

I hope Bob Kerrey can come to terms with it. I really do. But . . .

The women and children who died in the Mekong on February 25,1969 do not have the living luxury of shame and reassessment. Neither do the “NVA nurses.” The most any of us can do for them now is tell their story, in all its truthful brutality, and tear down the walls of denial that stand between a people and their consciousness.

If you want meaning, that’s all the meaning I’ve got.

Tags

Stan Goff

Stan Goff is an associate of the Institute's Southern Voting Rights Project (2003)