This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 30 No. 1/2, "Missiles and Magnolias: The South at War." Find more from that issue here.

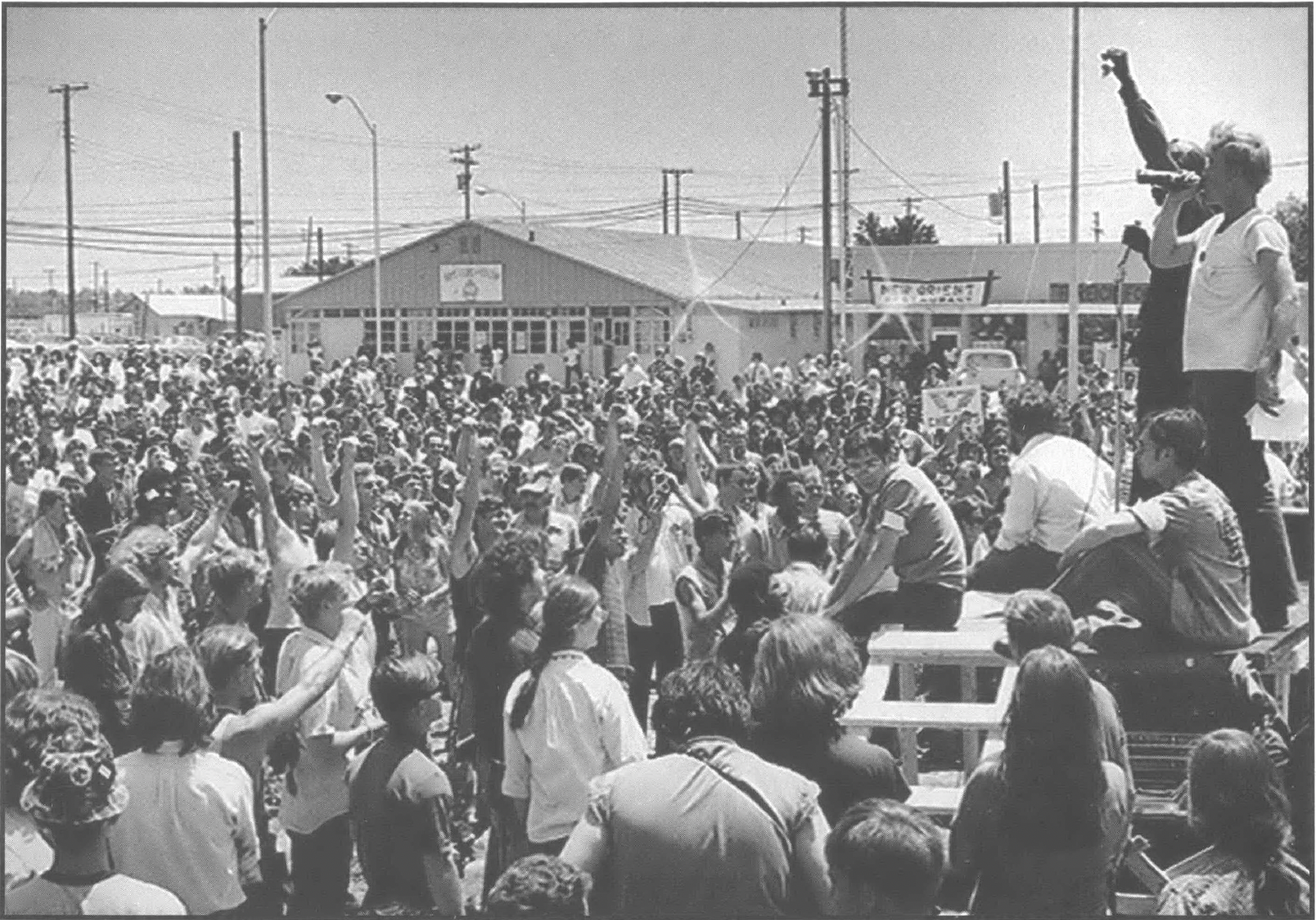

In the late 1960s, anti-war organizing moved from college campuses to military bases where enlisted soldiers openly defied U.S. militarism and organized to end the war in Vietnam. All these efforts, part of a submerged radical history, were centered around Gl coffeehouses such as the Oleo Strut at Fort Hood in Texas, the UFO at Fort Jackson in South Carolina, and the project Reed helped initiate at Fort Bragg in North Carolina.

A New Challenge For a Young Organizer

In the fall of 1969 I left Chapel Hill, North Carolina, where I’d been in college and involved in anti-war, student and labor organizing activities, to go to Fayetteville as part of a group intending to set up a Gl-organizing project. I had just been involved in a long, grueling, and very intense strike by non-academic employees at the university, during the course of which I was among a number of people arrested and convicted for our strike support activity. After the strike, I felt that it was time for me to leave campus organizing, as did the North Carolina authorities. (The terms of my two-year probation included a prohibition on engaging in any “disruptive” activity on the campus of any public education institution.)

At the same time, though, I had become friends with a grad student who earlier had helped set up the Oleo Strut at Fort Flood, Texas, and the UFO at Fort Jackson in South Carolina, two of the first GI antiwar coffeehouses. Through him I got to know Howard Levy, a dermatologist who had been court-martialed and imprisoned for his political activities — including his refusal to train Green Berets in dermatological torture techniques. They talked to me about a plan originating from the United States Servicemen’s Fund, the group that funded and raised money for antiwar coffeehouses, to recruit people to begin a project at Fort Bragg, and they asked me to consider being part of the group.

I hadn’t been thinking about doing anything remotely like GI organizing. However, I had done a great deal of anti-war work and had some experience with “Fayettenam,” as it was commonly called. A year earlier I was part of a group that got arrested passing out anti-war leaflets on post. So I’d already had an up-close and personal encounter with the 503rd MPs, seen the inside of the stockade, been permanently banned from the base, tried before the U.S. Commissioner and threatened with being sent to federal prison, escorted to the county line by state troopers, and tailed and threatened on the highway by either Klansmen or military intelligence.

What Better Place to Fight Against the War?

As I thought it over, going to Fayetteville made more and more sense. What better place to fight against the Vietnam War than Fort Bragg? It was at that time the largest military installation in the world with a permanent party (counting Pope Air Force Base that served it) of 83,000, and it was home to the 82nd Airborne Division, 18th Airborne Corps, Special Forces, and the JFK School of Special Warfare. In addition, the 53rd did riot duty up and down the East Coast, and Bragg was a basic training center.

Also, I knew the other people who were going to be part of the project and considered them good friends and comrades. We had all worked together frequently. We were all serious, level-headed and experienced organizers. We all trusted and respected one another and generally got along well. Trust and respect were more important than friendship, though I think it was a common experience that those with whom one became really friendly were those whose judgment one trusted. We were all in the middle of a dynamic movement that had a real constituency to be accountable to, with formidable adversaries who weren’t afraid of violence or sabotage.

Building the Coffeehouse

We decided to organize into two distinct but closely coordinated projects: one focusing on working with black troops, the other with white troops. Our thinking, with which organizers at several other coffeehouses disagreed, was that at that point it didn’t make sense to try to organize black and white soldiers into the same organization, at least not at Bragg. Racial polarization on post was intense, and black troops had formed an independent black power group. I suspect, though, that what was true at Bragg was true more generally and that activists elsewhere didn’t want to acknowledge the fact. For instance, organizers from the Camp Pendleton project used to travel around with a black marine and a white marine to show off “interracial proletarian solidarity.”

Before we moved to Fayetteville, a few of us visited the Fort Dix coffeehouse in New Jersey to see how a functioning project operated. Everyone was security conscious; the Fort Dix coffeehouse had been firebombed recently. We made up a cover story that we were thinking about setting up a project at Fort Polk in Louisiana just to try to misdirect military intelligence for long enough to acquire leases in Fayetteville.

In retrospect, they probably knew anyway, but the intelligence apparatus’ inefficiency may have given us some operating room. Once we got to Fayetteville, however, we experienced constant surveillance and petty intimidation from city and county law enforcement agencies as well as the military.

We were able to get set up in Fayetteville and pretty much hit the ground running. One of the organizers with the white project had been working in the city for some time with the Fayetteville Area Poor People’s Organization (FAPPO). Both GIs United Against the War and the smaller Black Brigade (later, the Black Servicemen’s Union) had been meeting for a time at the Quaker House, a center for anti-war and progressive activities generally in the city.

Bridges Between Black GIs and Black Civilians . . .

Not long after getting more intimately involved with black troop life, we realized that it would be tactically necessary and politically interesting to link GI organizing efforts with the work going on in the city’s black community. Black soldiers and black Fayettevillians were alien to each other in ways that at first impeded organizing on both sides.

Black GIs tended to repair to black Fayetteville for R & R, a sort of more familiar, local version of Thailand. When they were in that mode, they were both uninterested in local issues and often hostile to any serious undertakings like rallies, meetings, political discussion or demonstrations. To the extent that they maintained relationships with — and exerted depoliticizing pressure on — women in town, this attitude was a major source of tension with FAPPO, which worked almost exclusively in black communities and whose most active participants were female.

On the other side of the ledger, we hoped that joint organizing would help to humanize GIs and, ideally, build anti-war, antimilitarist and anti-imperialist consciousness among FAPPO’s main constituencies and in black Fayetteville at large. At its height, FAPPO had a membership of over 2,000 and was well known as a center of black activism in the area. They organized the local chapters of the National Welfare Rights Organization and the National Tenants Organization.

After some time, the Black Servicemen’s Union gained representation on FAPPO’s governing council, and the groups worked closely together in planning and executing projects. For instance, when Representative Ron Dellums of California came through on his tour of the stockades, he addressed a FAPPO mass meeting in a housing project. Not only did this address prompt a new wave of infiltrators from Military Intelligence but it almost got Dellums arrested when he couldn’t find his congressional immunity badge after upbraiding a racist cop who had harassed the occupants of the car taking him to the meeting.

. . . In Combined Community Organizing

We found ways to involve GIs in community issues, which in turn provided a basis for their broader political education. And linking the role the military played in Vietnam to the role it played in Fayetteville helped broaden the focus and perspectives of community activists.

An early, unsuccessful effort to get the Army to pave unpaved streets in the city’s poor, black neighborhoods was a nice educational vehicle, especially for youth organizing. (I had mixed emotions about this initiative because of the counter-productive implications of a possible victory. The Army certainly would have treated it as part of its domestic public relations work. They were already dropping in Green Berets to do service work in isolated, rural communities in the mountains and on the coast.) Actually, FAPPO’s reputation and practice were such that it wasn’t necessary to designate special youth initiatives. When young people — for example, in a controversy growing out of racial injustice in meting out discipline at a local high school — began to consider political activism, they naturally sought out FAPPO’s assistance and guidance.

Real War Stories?

Another virtue of the joint GI-community focus was that it was a counterweight to the militarist and adventurist rhetoric to which many GIs were disposed. First-timers at meetings often would express impatience with a notion of politics less flamboyant or more elaborate than “picking up a gun.” I remember one man, who went off on a diatribe about how the racist Russians were giving the Vietnamese guns to “kill brothers.”

I’ve wondered over the years whether he really had such wacky politics or if he was just a too enthusiastic agent. Some people were just looking for something to attach themselves to, the simpler and more formulaic the better. I recall cases of guys who went from the Black Panthers to the Nation of Islam to other sects and maybe back again in the span of a few months; this was no different from what one saw on campuses. The Black Panthers, who — on the East Coast, at least — related to the GI movement in a decidedly opportunistic way, fueled this kind of rhetoric and created all sorts of openings for provocateurs.

One of the most bizarre cases I encountered was of a guy who just materialized in town, alleging to be a Panther, and made contacts with a small group of black Special Forces NCOs (non-commissioned officers). This was already weird because very few NCOs supported political work, and Special Forces troops, unsurprisingly, had not been all that receptive. Fayetteville’s town center revolved around a former slave market, which had been restored — rebuilt, actually, because Sherman’s troops had blown it up on their way through town during the Civil War — and preserved, supposedly as a symbol of town pride.

Groups of black people in the city had talked off and on since the 1940s about blowing it up again, and this kind of musing was common in the late 1960s and early 1970s. This “Panther,” though, had a different idea. His plan was to rip off an arms room in the Special Forces area, move into the slave market and proclaim the revolution. The black community supposedly would rise spontaneously in support to boycott all white businesses and provide a cover of disruption for the guerilla band to withdraw to the countryside to begin systematic guerilla warfare. We were able to defuse that scheme at a very tense meeting in a trailer park, and the supposed Panther vanished just as suddenly as he had shown up.

The Seeds We Planted

I wish that I could report more dramatic and inspiring successes. We had small, finite accomplishments — like winning victories for individual soldiers against arbitrary and unjust punishment and discriminatory treatment, and creating a climate in which several troops refused to do riot duty for the Panther trial in New Haven and planned to refuse mobilization when they were put on alert to go to Jordan in 1970. There were more in the community organizing as well.

Our main victories, however, were in developing the politics of those who were involved in the efforts. This applies not only to the organizers and activists themselves; in later years I’ve come across people who were adolescents and preteens in Fayetteville during that period and report being shaped in their politics by our work and presence in the area.

All these small victories, both concrete and otherwise, are tiny pieces of a much bigger movement. Most immediately, they were our contribution — along with many, many other bigger and smaller ones — to ending the Vietnam War by cultivating dissent and creating a climate that threatened to raise the cost of maintaining domestic social peace if it continued. In the longer view, we helped to develop a cadre of activists who’ve gone on from there to engage in struggles elsewhere for decades.

I know that I found some of my closest friends and comrades in that activity; intense political struggles confer a particular kind of enduring trust and mutuality upon those who participate intimately in them. And that is a basis for building subsequent political relationships. At the same time, however, I returned to Fayetteville at the dawn of the Reagan era after several years’ absence, and it was all too easy to find my old FAPPO coworkers. They still lived on the same unpaved streets, still worked the same unrewarding jobs. That’s a sobering reminder that we didn’t win. There’s still a great deal of work to be done.

Tags

Adolph Reed Jr.

Adolph Reed Jr. is a professor of political science at New School University in New York and the author of The Jesse Jackson Phenomenon, W. E. B. Du Bois and American Political Thought, Stirrings in the Jug, and Class Notes. (2002)