This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 28 No. 1/2, "Lies Across the South." Find more from that issue here.

“He sings more sincere than most entertainers because the hillbilly was raised rougher than most entertainers. “

— Hank Williams

Through the century, country music has always had to contend with marketing strategies aiming to balance roots and mass appeal. But in the last two decades, as country music has exploded to unprecedented commercial success, this “balance” has become so laced with pop and rock influences, the very identity of the music has been called into question. What’s now being billed as “Real Country” is, in fact, an exclusion of most of the Grand Tradition’s historical and musical legacy.

In the 1920’s, when country music first began to feel the pressures of commercialization, rural traditions of all kinds were experiencing tensions and challenges brought on by industrialization. Country sounds suggesting older and more settled ways seemed inherently at odds with rapid social and technological change. The music expressed a longing for stability and order and deep-seated fears of the temptations of the modern world. At the same time, the music could not help but reflect hopes of escaping the hardships associated with traditional rural life.

Conflicted feelings also derived from the Southerness of the music. While the music of Stephen Foster and the writings of Mark Twain fueled romantic notions of the South as an exotic land of enchantment, the region also evoked images of slavery and the Civil War, the Scopes monkey trial, and the Klan. Thus for many, country music, regardless of its subject matter, was nothing more than the sound of ignorance and racism.

Retaining a stubborn self-consciousness of its white, rural, Southern, working class origins, country music today continues to attract and repulse listeners by stirring the same opposing images. Nonetheless, in a span of 70 years, country music has grown from regional to national and international popularity.

With mass popularity, however, some of the most distinctive qualities of country music have been diluted. Listening to the musical styles dominating country radio, one hears a generic McDonald’s styled product so stripped of “hayseed” connotations that it virtually erases the line between country and various forms of easy listening white pop and bland ’70s styled corporate rock. While more traditional sounds have not disappeared, the Nashville industry bias toward an urban-suburban contemporary sound has certainly muddled the definition and origins of the musical idioms known as country.

Like other music forms of our culture, country music is an amalgam of influences. Its sound, song structure, and lyrical text reveal a heavy debt to African-American musical styles, particularly blues and gospel. Rhythmically, country draws most on the dance meters of English and European country dance tunes. As to lyrics and narrative style, country storytelling has roots in Southern Protestant sermonizing, barroom banter, front porch story swapping, and the general character of regional oral traditions.

Yet historically the most dominant and unmistakable quality of the country sound is sadness. One of the great stereotypes plaguing country music is the cry-in-the-beer loser drowning the pain of romantic loss in some dark tavern. But the heartbreak in country music runs deeper than cheating, drinking, and divorce. The sad tale country music has to tell goes back to the devastation the region suffered during the Civil War, the loss of rural identity, and the great migration of Southerners to urban centers in the Midwest and West during the 1940s and 1950s. These experiences have given country music a deeply embedded memory of social dislocation. Understandably therefore, country music is homesick music, permanently colored by feelings of longing and lost innocence.

The loss at the heart of the country song has been expressed through two divergent impulses. When the Carter Family and Jimmie Rodgers came to Bristol, Tennessee, in August 1927 to perform before record scout Ralph Peer and a Victor Talking Machine, they brought with them distinct bodies of material representing seemingly contradictory themes and values. In the Carter Family’s huge repertoire of traditional songs resided the morally decent old-time virtues of work, family, humility, and Christian fellowship.

By contrast, Rodgers, an ex-railroad brakeman from Meridian, Mississippi, penned tunes with roots in blues and jazz, folk and cowboy songs, work gang hollers and pop. Though Rodgers wrote his share of songs glorifying the home and family, his work also celebrated the lives of hell-raisers, hobos, wayward lovers, criminals, rounders and ramblers.

Both approaches proved immediately popular.

Though commercialization accelerated the homogenization of country sounds, by documenting the diversity of local and regional styles it also helped Southerners gain a fuller sense of their common cultural heritage. The music labeled “hillbilly” dramatized what they suffered, survived, and left behind. It offered solace and understanding, realism and escape. But most of all, it was music that responded to change with a reassertion of tradition.

Because of this emphasis on Southerness and tradition, country music has long been associated with all that is reactionary. However, while country music generally expresses a conservative outlook, the view of country as an exclusively white, male-dominated, right-wing tradition is unfair and one-dimensional. At no point in its history has country music expressed a consistent political ideology. For every hard-headed patriotic diatribe like “Okie From Muskogee,” there’s a left-bent protest like Waylon Jennings’ multicultural, egalitarian anthem “America” or James Talley’s ode to populist rebellion “Are They Gonna Make Us Outlaws Again.”

More importantly, since country music has always been a voice for small farmers, factory hands, day laborers, the displaced and unemployed, its harsh portraits of work and everyday life carry an implicit critique of capitalism. Instead of overt political protest, however, country songs prefer to deliver social criticism through poignant descriptions of economic hardship and family sacrifice. Some of the best examples of this style of protest are Merle Haggard’s “Mama’s Hungry Eyes,” Dolly Parton’s “Coat of Many Colors,” and Loretta Lynn’s “Coal Miner’s Daughter.”

As to the issue of race, country music’s sentimental attachment to Dixie is often taken as an endorsement of white supremacy and slavery. Country music’s glorification of the South, however, derives mostly from an idealized notion of working the land and the real life movement of millions off the land during the years of the Great Depression and World War II. Not surprisingly, hundreds of country tunes plead the case of the farmer and celebrate the beauty of Southern landscapes.

Still, it is obvious that “whiteness” is dominant in country music. Despite the tradition’s enormous debt to African-American music and other ethnic music cultures, nonwhite performers are still exceedingly rare in country music. And when voices of color have gained popularity in the country field, it has generally been through songs and styles evidencing only traces of their racial origins.

Nonetheless, since the 1960s Mexican-Americans such as Johnny Rodriguez, Freddy Fender, Tish Hinojosa, and Flaco Jiminez and African Americans such as Charlie Pride, Stoney Edwards, and Big Al Downing have won acceptance with country audiences. And occasionally, there are tunes like Bobby Braddock’s “I Believe the South Is Gonna Rise Again” suggesting a new progressive vision of racial unity:

The Jacksons down the road were poor like we were

But our skin was white and theirs was black

I believe the South’s gonna rise again

But not the way we thought it would back then

Some of the strongest stereotypes attached to country music revolve around the social and sexual roles of women. To many people Tammy Wynette’s 1968 hit “Stand By Your Man” typifies the passive, long suffering mentality of the unliberated country woman. In truth, the female perspective in country music is much broader and far more assertive than this superficial stereotype can allow.

The richest and most authoritative evidence of this reality can be found in Mary Bufwack and Robert Oermann’s Finding Her Voice: The Saga of Women In Country Music (Crown Publishers Inc., New York). Exploring the folk origins of country music, Bufwack and Oermann argue that women were the primary folklorists for early rural music, memorizing the tunes and lyrics that provided the basic entertainment for the family and community. And in their own original ballads, women expressed sexual fantasies and discontents in songs loaded with images of romantic longing, promiscuity, violence, and death. Bufwack and Oermann also reveal more active and socially oriented resistance in the depression era songs of Sarah Gunning, the composer of “I Hate the Capitalist System,” and Aunt Molly Jackson, who began making up class conscious songs and walking picket lines before she was 10.

It was not until the 1950s, however, that women in country music began to gain commercial equality with men. Following Kitty Wells’ surprising 1952 hit “It Wasn’t God Who Made Honky Tonk Angels” — a woman’s retort to Hank Thompson’s “The Wild Side of Life” — women singers such as Patsy Cline, Loretta Lynn, Dolly Parton, and Tammy Wynette started achieving record sales and stardom rivaling men.

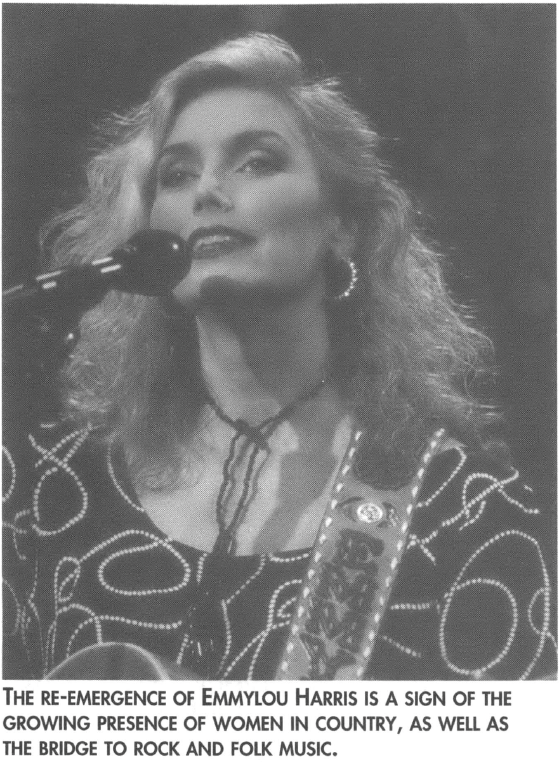

By 1984 about one-fourth of the top country singles and albums were by women. And today’s country and pop charts are overflowing with country women — Reba McEntire, Wynonna Judd, Mary Chapin-Carpenter, Trisha Yearwood, Suzy Bogguss, Patty Loveless, Pam Tillis, and the hugely popular Dixie Chicks, to mention only a few. Most significantly, the commercial appeal of the current generation of country women seems directly linked to a feminist-oriented lyric.

While the politics of country music eludes many popular prejudices and neat categories of left and right, however, the fundamental conservatism of the message cannot be denied. Country music may be one of the truest forms of popular music in the way it gives voice to the bitter realities of class and the sorry state of male-female relations. But in offering few avenues of escape and rebellion, country music tends to settle struggle in favor of the powers that be.

Nonetheless, country’s stoic acceptance of things as they are cannot be taken as an unqualified endorsement of the status quo. The great strength of country music has been its ability to capture white working class life as it really is and without the projection of false hope. And in this realistic assessment of limits, the music contradicts societal ideals of progress, success, and fairness. Accordingly, throughout most of its commercial history, country music has been dismissed as something beneath and apart from mainstream culture.

Fully aware of country music’s “negatives,” the Nashville music establishment has periodically regroomed the sound and image of the tradition with hopes of winning respectability and crossover appeal. In the 1950s and ’60s, it was the smooth, urbane “Nashville Sound,” in the 1970s it was the tasteless pop country of John Denver and Olivia Newton-John, and in the 1980s it was Urban Cowboy role playing. Although all of these trends gave country a temporary commercial boost, hardcore country fans and musicians reacted to each with a purist backlash (bluegrass, the Bakersfield sound, Willie Nelson and Waylon Jennings’ “outlaw” movement, neo-traditionalism) that eventually brought the market back around to traditional sounds.

In the Reagan-Bush-Clinton era, country music has slowly ascended again to mainstream popularity with sounds and images revealing few traces of country’s old-time hickishness. This time around, country’s new audience seems to come from aging white boomers and younger middle-income suburbanites who’ve tired of classic rock and can’t tolerate aggressive youth sounds (metal, hip-hop, alternative rock) or easy listening pop. For these listeners (one survey indicates that over a third of the country audience has postgraduate degrees and incomes exceeding $100,000), country supplies a guitar based rock influenced sound, adult subject matter, and yearning for a more simple and decent way of life.

Unfortunately in meeting this demand, the music industry has again resorted to formula: muscles, big hats, starched boot cut Wranglers, choreographed sexy moves, and pale, twang-free impersonations of heartbreak. Today’s country music is embarrassed by its past. And despite all the promotional claims for “Modern” and “Young” country, mainstream country lyrics give little hint of present day social and economic reality.

In response, another vaguely defined movement of non-mainstream country has reared its head and slowly carved out a small but growing national audience. Sometimes called roots music, alternative country, insurgent country, or Americana, this loosely defined mutant country, has evolved through the ’90s while pulling together a mongrel community of music listeners and musicians attracted to Appalachian folk music, blues, depression era country, post-World War II honky tonk, bluegrass, country rock and punk. In short, music that carries a sense of time, place, class, tragedy and resilience.

No surprise then that some of the greatest heroes of the current “not Nashville” wave include country and folk legends such as the Carter Family, Jimmie Rodgers, Dock Boggs, Woody Guthrie, Bob Wills, the Louvin Brothers, Hank Williams, Kitty Wells, Tammy Wynette, George Jones, Johnny Cash and Merle Haggard. But since this is a largely rock-informed crowd, influences also include Bob Dylan, Gram Parsons, Neil Young, the Clash, Charles Bukowski and X. With such a wide range of inspirations, so-called “alternative country” is stylistically all over the place.

From the singer-songwriter camp come distinctive voices like Jimmie Dale Gilmore, Steve Earl, Gillian Welch, Iris Dement and Lucinda Williams. Established country performers with strong tradition based styles, such as Dwight Yoakam, Emmylou Harris and Alison Krauss, are included. The fresh swinging barroom sounds of Wayne Hancock, BR-549 and Junior Brown make a natural fit. And from the younger breed of country rockers come bands such as Son Volt, Wilco and Whiskeytown.

So far, however, this unclassifiable movement seems to have too many rough edges to make a mainstream crossover. To begin with, most of the musicians are far too scruffy to win over audiences weaned on an army of slick “hat acts.” Beyond problems of image, there’s music and words that are a little too fresh and lived in to be easily absorbed by Young Country fans unaccustomed to unpolished singers howling their misery and desire.

Still country music has always returned to its roots following periods of pop like homogenization. In the mid-’90s, country music record sales topped two billion dollars and nearly seventy million people reported they listened to country music on the radio over all other styles of music. Yet since that time, country record sales and the country radio audience have been sliding steadily downward. While this trend may not signal the end of “cookie cutter” country, it’s at least a sign that Nashville’s current formulas are wearing thin.

Though the varied brands of offbeat country may never coalesce into a next big thing, all the ill labeled twangers going about their business below the Top 40 are forging vital links between tradition and today. In the progressive new voice of women, left-of-center hillbilly folk, Bakersfield rooted hard country, bluegrass, and punk informed country rock, you can still hear the raw emotions and wild and blue stories of a truly populist art form. The “old” story country music has to tell is simply too real, too rooted, and too timeless to be forgotten.

Tags

Sandy Carter

Sandy Carter was born in Gulfport, Mississippi and grew up in Amarillo, Texas, listening to the music of Bob Wills, Lefty Frizzell, and Hank Williams. He writes the “Slippin’ & Slidin’” column on music and culture for Z Magazine. (2000)