Who Killed Martin Luther King?

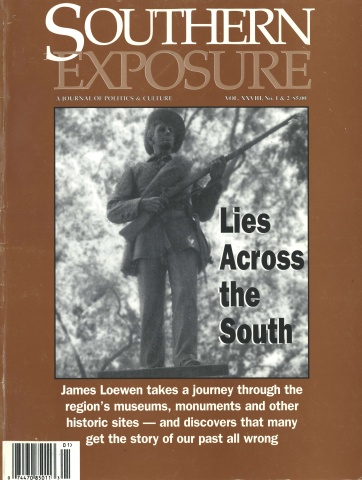

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 28 No. 1/2, "Lies Across the South." Find more from that issue here.

On December 8, 1999, a jury in Memphis, Tennessee, deliberated for only three hours before deciding that the long-held official version of Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination was wrong. The jury’s verdict implicated a retired Memphis businessman and government agencies in a conspiracy to kill the civil rights giant.

Though the trial testimony had received little press attention outside of the Memphis area, the startling outcome drew an immediate rebuttal from defenders of the official finding: that James Earl Ray acted alone or possibly as part of a low-level conspiracy of a few white racists.

Leading newspapers across the country disparaged the December verdict as the product of a flawed conspiracy theory given a one-sided presentation. The Washington Post even lumped the conspiracy proponents in with those who insist Adolf Hitler was unfairly accused of genocide. “The deceit of history, whether it occurs in the context of Holocaust denial or in an effort to rewrite the story of Dr. King’s death, is a dangerous impulse for which those committed to reasoned debate and truth cannot sit still,” a December 12, 1999 Post editorial read. “The more quickly and completely this jury’s discredited verdict is forgotten the better.”

For its part, the King family cited the verdict as a way of dealing with its personal grief. “We hope to put this behind us and move on with our lives,” said Dexter King, speaking on behalf of the family. “This is a time for reconciliation, healing and closure.”

But should closure — or forgetfulness — follow a verdict that finds the federal government complicit in a conspiracy to assassinate one of this nation’s most historic figures? Are there indeed legitimate reasons to doubt the official story? And how should Americans evaluate this unorthodox trial, its evidence and the verdict?

A Reason to Doubt

Without doubt, the trial in Memphis lacked the neat wrap-up of a Perry Mason drama. The testimony was sometimes imprecise, dredging up disputed memories more than three decades old. Some testimony was hearsay; long depositions by deceased or absent figures were read into the record; and some witnesses had changed their stories over time amid accusations of profiteering.

There was a messiness that often accompanies complex cases of great notoriety. The plaintiff’s case also did not encounter a rigorous challenge from Lewis K. Garrison, the attorney for defendant Loyd Jowers. Garrison shares the doubts about the official version, and his client, Jowers, has implicated himself in the conspiracy, although insisting his role was tangential. Some critics compared the trial to a professional wrestling match with the defense putting up only token resistance.

Yet, despite the shortcomings, the trial was the first time that evidence from the King assassination was presented to a jury in a court of law. The verdict demonstrated that 12 citizens — six blacks and six whites — did not find the notion of a wide-ranging conspiracy to kill King as ludicrous as many commentators did.

The trial suggested, too, that the government erred by neglecting the larger issue of public interest in the mystery of who killed Martin Luther King Jr. Instead the government simply affirmed and reaffirmed James Earl Ray’s guilty plea for three decades. Insisting that the evidence pointed clearly toward Ray as the assassin, the government never agreed to vacate Ray’s guilty plea and allow for a full-scale trial, a possibility that ended when Ray died from liver disease in 1998.

At that point, the King family judged that a wrongful death suit against Jowers was the last chance for King’s murder to be considered by a jury. From the start, the family encountered harsh criticism from many editorial writers who judged the conspiracy allegations nutty.

The King family’s suspicions, however, derived from one fact that was beyond dispute: that powerful elements of the federal government indeed were out to get Martin Luther King, Jr., in the years before his murder. In particular, FBI director J. Edgar Hoover despised King as a dangerous radical who threatened the national security and needed to be neutralized by almost any means necessary.

After King’s “I have a dream speech” in 1963, FBI assistant director William Sullivan called King “the most dangerous and effective Negro leader in the country.” Hoover reacted to King’s Nobel Peace Prize in 1964 with the comment that King was “the most notorious liar in the country.”

The documented record is clear that the FBI and other federal agencies aggressively investigated King as an enemy of the state. His movements were monitored; his phones were tapped; his rooms were bugged; derogatory information about his personal life was leaked to discredit him; he was blackmailed about extramarital affairs; he was even sent a message suggesting that he commit suicide. “There is only one way out for you,” the message read. “You better take it before your filthy, abnormal, fraudulent self is bared to the nation.”

These FBI operations escalated as black uprisings burned down parts of American cities and as the nation’s campuses erupted in protests against the Vietnam War. To many young Americans, black and white, King was a man of unparalleled stature and extraordinary courage. He was the leader who could merge the civil rights and anti-war movements. Increasingly, King saw the two issues as intertwined, charging that President Lyndon Johnson was siphoning off anti-poverty funds to prosecute the costly war in Vietnam.

On April 15, 1967, less than a year before his murder, King concluded a speech to an anti-war rally with a call on the Johnson administration to “stop the bombing.” King also began planning a Poor People’s March on Washington that would put a tent city on the Mall and press the government for a broad redistribution of the nation’s wealth.

Covert government operations worked to disrupt both the anti-war and civil rights movements by infiltrating them with spies and agents provocateurs. The FBI’s COINTELPRO sought to neutralize what were called “black nationalist hate groups,” counting among its targets King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference. One FBI memo fretted about the possible emergence of a black “Messiah” who could “unify and electrify” the various black militant groups. The memo listed King as “a real contender” for this leadership role.

The Manhunt

With this backdrop came the chaotic events in Memphis in early 1968 as King lent his support to a sanitation workers’ strike marred by violence. The government’s surveillance of King in Memphis — by both federal agents and city police — would rest at the heart of the case more than three decades later. On April 4, 1968, at 6 p.m., King emerged from his room on the second floor of the Lorraine Motel. As he leaned over the balcony, King was struck by a single bullet and died.

As word of his death spread, riots exploded in cities across the country. Fiery smoke billowed from behind the Capitol dome. Government officials struggled to restore order and police searched for King’s assassin.

One of those questioned was restaurant owner Loyd Jowers, whose Jim’s Grill was below the rooming house where James Earl Ray had stayed and from where authorities contend the fatal shot was fired.

Jowers told the police he knew nothing about the shooting, but had heard a noise that “sounded like something that fell in the kitchen.” (The Commercial Appeal, Dec. 9, 1999)

The international manhunt ended at London’s Heathrow Airport on June 8, 1968, when Scotland Yard detained Ray for carrying an illegal firearm. Ray was extradited back to the United States to stand trial as King’s lone assassin.

The FBI insisted that it could find no solid evidence indicating that Ray was part of any conspiracy. But the authorities contended they had a strong case against Ray, including a recovered rifle with Ray’s fingerprints. The rifle fired bullets of the same caliber as the one that killed King.

While Ray sat in jail, Jowers’ name popped up again in the case. On Feb. 10, 1969, Betty Spates, a waitress at Jim’s Grill, implicated Jowers in the assassination. She said Jowers found a gun behind the cafe and may actually have shot King. Two days later, however, Spates recanted. (The Commercial Appeal, Dec. 9, 1999)

On March 10, 1969, Ray accepted the advice of his attorney and pleaded guilty. He was sentenced to 99 years in prison. Three days later, however, he wrote a letter to the judge asking that his guilty plea be set aside. He claimed that he was innocent and that his lawyer had misled him into making the plea. Ray began telling a complex tale in which he was duped by an operative he knew only as “Raul.” Ray claimed that Raul arranged the assassination and set Ray up to take the fall.

Government investigators rejected Raul’s existence and insisted that Ray was simply spinning a story to escape a long prison term. The courts rejected Ray’s request for a trial. As far as the legal system of Memphis was concerned, the case was closed.

But there did appear to be weaknesses in the prosecution case that might have shown up at trial. For instance, Charles Stephens, a key witness placing Ray at the scene of the crime, appeared to have been drunk at the time and had offered contradictory accounts of the assailant’s description, according to a reporter who encountered him after the shooting. (For details, see William F. Pepper’s Orders to Kill.) Outside the government, other skeptical investigators began to pick at the loose ends of the case.

In 1971, investigative writer Harold Weisberg published the first dissenting account of the official King case in his book, Frame Up. Weisberg noted problems with the physical evidence, including the FBI’s failure to match the death slug to the alleged murder weapon. Questions about the case mounted when the federal government declassified records revealing the intensity of FBI hatred for King. The combination of factual discrepancies and a possible government motive led some of King’s friends to suspect a conspiracy.

In 1977, civil rights leader Ralph Abernathy encouraged lawyer William F. Pepper to meet with Ray and hear out the convict’s tale. Pepper said he took on the assignment in part because he had encouraged King to join in publicly criticizing the Vietnam War and felt a sense of responsibility for King’s fate.

Responding to growing public doubts about the official accounts of the three major assassinations that rocked the nation in the 1960s, Congress also agreed to re-examine the murders of President John F. Kennedy, Sen. Robert F. Kennedy and King.

In congressional testimony, however, Ray came off poorly. Rep. Louis Stokes, D-Ohio, the chairman of the investigating committee, said Ray’s performance convinced him that Ray indeed was the assassin and that there was no government role in the murder.

The panel did leave open the possibility that other individuals were involved, but limited the scope of any conspiracy to maybe Ray’s brothers, Jerry and John, or two St. Louis racists who allegedly put a bounty on King’s life. But others on the panel, such as Rep. Walter Fauntroy, D-D.C., continued to harbor doubts about the congressional findings.

The King Family Charges Conspiracy

After a decade of on-and-off work on the case, Pepper decided to press ahead. He agreed to represent Ray and filed a habeas corpus suit on his behalf. Also, in 1993, a mock television trial presented the evidence against Ray to a “jury,” which returned the convict’s “acquittal.” Pepper asserted that the government’s case was so weak that Ray would win a regular trial, too.

Jowers reentered the controversy as well, reversing his initial statement to police denying knowledge of the assassination. On Dec. 16, 1993, in a nationally televised ABC-TV interview, Jowers claimed that a Mafia-connected Memphis produce dealer, Frank C. Liberto, paid him $100,000 to arrange King’s murder.

But Liberto was then dead and the man named by Jowers as the paid hit-man denied any role in the murder. (The Commercial Appeal, Dec. 9, 1999)

In 1995, Pepper published an account of his investigation in Orders to Kill. The book contended that the conspirators behind the assassination included elements of the Mafia, the FBI, and U.S. Army intelligence. Pepper located witnesses with new evidence. John McFerren, a black grocery owner, was quoted as saying that an hour before the assassination, he overheard Liberto order someone over the phone to “shoot the son of a bitch when he comes on the balcony.”

But Pepper’s credibility suffered when he cited anonymous sources in identifying William Eidson as a deceased member of a U.S. Army assassination squad that was present in Memphis on the day King died. ABC-TV researchers found Eidson to be alive and furious at Pepper’s insinuations about his alleged role in the King assassination.

Still, the King family — especially King’s children — grew increasingly interested in the controversy. On March 27, 1997, King’s younger son, Dexter, sat down with Ray in prison, listened to Ray’s story and announced his belief that Ray was telling the truth. In a separate meeting with the King family, Jowers claimed that a police officer shot King from behind Jim’s Grill. The officer then handed the smoking rifle to Jowers, the former restaurant owner said.

The authorities in Tennessee, however, continued to rebuff Ray’s appeals for a trial. Prosecutors concluded that Jowers’ story lacked credibility and may have been motivated by greed. Ray’s pleas for his day in court finally ended with his death from liver disease.

On Oct. 2, 1998, the King family filed a wrongful death suit against Jowers. The trial opened in November 1999, attracting scant attention from the national press. Jowers, 73, attended only part of the trial, and did not testify. His admissions of complicity were recounted by others who had spoken with him.

Former United Nations ambassador Andrew Young testified that he found Jowers sincere during a four-hour conversation about the assassination. “I got the impression this was a man who was very sick [and who] wanted to go to confession to get his soul right,” Young said.

According to Young, Jowers said he had served Memphis police officers and federal agents when they met in Jowers’ restaurant before the assassination. Jowers also recounted his story of Mafia money going to a man who delivered a rifle to Jowers’ cafe. After the assassination, the man, a Memphis police officer, handed the rifle to Jowers through a back door, according to Jowers’ account. (Scripps Howard News Service, Nov. 18, 1999)

A former state judge, Joe Brown, took the stand to challenge the government’s confidence that Ray’s rifle was the murder weapon. During one of Ray’s earlier court hearings, Brown had ordered new ballistic tests on the gun and the bullet that killed King.

The results had been inconclusive, with the forensics experts unable to rule whether the gun was the murder weapon or was not. In his testimony, however, Brown asserted that the sight on the rifle was so poor that it couldn’t have killed King.

“This weapon literally could not hit the broadside of a barn,” Brown said. But he acknowledged that he had no formal training as a weapons expert.

The jury also heard testimony that federal authorities were monitoring the area around the Lorraine Motel. Carthel Weeden, a former captain with the Memphis Fire Department, said that on the afternoon of April 4, 1968, two men appeared at the fire station across from the motel and showed the credentials of U.S. Army officers.

The men then carried briefcases, which they said held photographic equipment, up to the roof of the station. Weeden said the men positioned themselves behind a parapet approximately 18 inches high, a position that gave them a clear view of the Lorraine Motel and the rooming house window from which Ray allegedly fired the shot that killed King.

They also would have had a view of the area behind Jim’s Grill. But what happened to any possible photographs remains a mystery. Weeden added that he was never questioned by local or federal authorities.

Former Rep. Fauntroy also testified at the King-Jowers trial. Fauntroy complained that the 1978 congressional inquiry was not as thorough as the public might have thought. The committee dropped the investigation when funding dried up and left some promising leads unexplored, he told the jury.

“Had we had [another] six months, we may well have gotten to the bottom of everything,” Fauntroy testified on Nov. 29. “We didn’t have the time to investigate leads we had established but could not follow. . . . We asked the Justice Department to follow up . . . and to see if there was more than just a low-level conspiracy.”

Other witnesses described a strange withdrawal of police protection from around the motel about an hour before King’s death. A group of black homicide detectives, who had served as King’s bodyguards on previous visits to Memphis, were kept from performing those duties in April 1968.

In his summation, trying to minimize his client’s alleged role in the conspiracy, Garrison asked the jury, “Would the owner of a greasy spoon restaurant, and a lone assassin, could they pull away officers from the scene of an assassination? Could they put someone up on the top of the fire station?”

The cumulative evidence apparently convinced the jury. After the trial, juror Robert Tucker told a reporter that the 12 jurors agreed that the assassination was too complex for one person to handle. He noted the testimony about the police guards being removed and Army agents observing King from the firehouse. “All of these things added up,” Tucker told the Associated Press.

The Media Backlash

Even before the trial ended, the media controversy about the case had begun. Many reporters viewed the conspiracy allegations as half-baked and the defense as offering few challenges to the breathtaking assertions. The jury, for instance, heard little about the gradual evolution of Jowers’ story, which began with a flat denial and grew over time with the addition of sometimes conflicting details.

In a commentary on the case, history writer John McMillian reaffirmed his confidence in Ray’s guilt and his certainty that the wrongful death suit was “misguided.” But McMillian noted that the King family’s suspicions about the government’s actions were grounded in the reality of the FBI’s campaign to ruin King’s reputation.

“While King was alive, he and his family suffered needlessly from slimy government subterfuge,” McMillian wrote. Though believing Ray was “justly punished for being King’s assassin,” McMillian wrote, “the FBI has never been held accountable for a much more lengthy, expensive and organized campaign to destroy King.”

Other critics focused on Pepper. Court TV analyst Harriet Ryan noted that the King family’s motivations appeared sincere, but “the same cannot be said for Pepper [who] stands to gain from sales of his book.” Gerald Posner, author of the conspiracy-debunking book, Killing the Dream, argued that the trial “bordered on the absurd” due to a “lethargic” defense and a judge who allowed “most everything to come into the record.”

Posner also cited money as the motive behind the case. He accused Pepper of misleading the King family for personal gain and suggested that the King family went along as part of a scheme to sell the movie rights to film producer Oliver Stone.

Pepper responded that a film project that the King family had discussed with Warner Bros, had fallen through before the civil case was brought. He noted, too, that the family sought and received only a token jury award of $100.

But the back-and-forth quickly muddied whatever new understanding the public might have gained from the trial.

Part of the confusion could be traced to the effectiveness of Posner and other critics in making their case in a wide array of newspapers and on television talk shows. Some of the blame, however, must fall on Pepper and his flawed investigation that did include some erroneous assertions.

The larger tragedy may be that the serious questions about King’s assassination have receded even deeper into the historical mist. As Court TV analyst Ryan noted, “Whatever theories Garrison and Pepper get into the record . . . it is not likely they will change the general belief that Ray was responsible.”

Though Ryan may be right, another perspective came in 1996 when two admirers of Dr. King — the Rev. James M. Lawson Jr. and actor Mike Farrell — wrote a fund-raising letter seeking support for a fuller investigation of the assassination. They argued that the full story of Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination was too important to the country to leave any stone unturned. They stated:

“There are buried truths in our history which continue to insist themselves back into the light, perhaps because they hold within them the nearly dead embers of what we were once intended to be as a nation.”

WHO DID IT? Leading MLK Assassination Theories

Compiled by Gary Ashwill. Al McSurely contributed research to this story.

The Lone Assassin: James Earl Ray

The FBI, the Memphis Police Department, and the Shelby County District Attorney’s office quickly united around the theory that an escaped felon named James Earl Ray pulled off the plan, the shot, and the getaway all by himself. This single-suspect theory has been extensively developed by a Wall Street attorney, Gerald Posner, in his book Killing the Dream: James Earl Ray and the Assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. Posner denies government involvement and the existence of a cover-up. Since Ray is the only suspect, the crime has been solved, and there is no need to examine who benefited from the murder.

The House Assassinations Committee: Other Players Involved

A congressional committee chaired by King’s close friend, Rep. Walter Fauntroy, concluded that Ray probably murdered King, but that he probably had help from his brother and possibly a racist St. Louis businessman. The highly partisan committee members had strong political motives — on one side, to find a government conspiracy; and on the other, to buttress the government position that Ray acted alone. Not surprisingly, the conclusion was a sort of compromise: a small, controlled conspiracy involving the Ray family and one or two others, but no one on any government payroll was involved. The Assassinations Committee’s report remains the best source of information on King’s murder.

Dick Gregory and Mark Lane: “Proof” of Government Involvement

Investigative journalist Mark Lane and civil rights activist Dick Gregory believe that there was government action two hours before the murder when a black detective was taken out of his surveillance spot. Det. Ed Redditt had been posted in the back of a fire station a few yards from the Lorraine Motel, not far from where the fatal shot was fired. He was there ostensibly to protect King, but was called in to Memphis police headquarters at 4 p.m. the day of the murder, about two hours before it occurred. There he was introduced to “a Secret Service agent from Washington” who had apparently instigated his removal, on the pretext of protecting Redditt from threats on his life.

The King Family and William Pepper: The Jowers Conspiracy

The King family and their lawyer, William Pepper — a 60s activist who had influenced King’s increasingly anti-war stance — have emphasized the testimony of Loyd Jowers, who owned Jim’s Grill just across the courtyard from the site of the murder. Jowers claims that there was a conspiracy, and that he was paid to participate in it. The shooter was probably an off-duty Memphis police officer, now deceased. A Memphis jury found the evidence convincing, and ruled against Jowers in a civil suit brought by the King family this past winter.

Tags

Douglas Valentine

Douglas Valentine is author of the 1990 book, The Phoenix Program. He has written for publications including Consortiumnews.com, where an earlier version of this story appeared. Valentine also worked as a researcher for the King family, and testified at the trial about U.S. government surveillance of King. (2000)