The Three of Them and Lucky

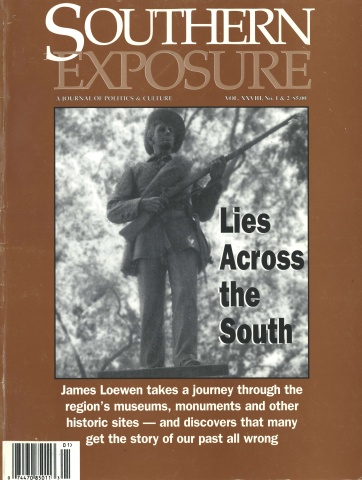

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 28 No. 1/2, "Lies Across the South." Find more from that issue here.

I feel it already. This will be one of those days. Samson, the fellow I’ve been with for a year now, tells me he’d like to be a fly on the wall. He says that about lots of days here in the Feed Room. He’s right. There’s always stuff going on you wouldn’t want to miss.

Today Penny perches at one end of the counter while Silo leans, propped on his elbows at the other, the two of them like bookends. I’ve spoken to Penny, act like I don’t see Silo settling Lucky, his blue tick hound, at his feet. As usual, he totally ignores the No Pets Allowed sign beside the door like Lucky is a special breed that’s exempt. Every morning we have a go ’round. Not only is the dog inside when she shouldn’t be, but primarily Lucky is a thief. I hate a thief, especially one that’s a dog.

With my back turned to them, I line up the catsup holders on the counter and fill them with the fat packages that squirt down your front when you rip off the corner. We’ve used them since Minnie Roundtree from the We-Kare saw Tan Mason lick his knife then stick it in a bottle of catsup. Miss Minnie said it like to have turned her stomach.

I wonder about her sometimes. She’s been to the Feed Room enough to know she’s not putting her feet under a table at the Waldorf.

Things are slow. The breakfast crowd has thinned. Dinkins has picked up Miss Minnie and taken her back to the We-Kare. He brings her over in the van every morning, makeup caked in heavy streaks from her cheeks to her chin, but her forehead is bare like she’s forgotten it’s up there.

She orders The Deluxe, two eggs over light, toast and a sausage patty — links give her heartburn. I can sympathize with her. I have stomach trouble and shy away from spicy stuff myself. She says it’s hard to face old man Harley at the nursing home on an empty stomach, forking scrambled eggs into his mouth, missing more often than not. He puts his dentures in when he’s done with his morning coffee, so other than breakfast, meals at the We-Kare are tolerable.

It’s not often the Feed Room is a step up in anybody’s estimation, although we do maintain a standard — no dirty talk, no jokes about blacks, Jews, Polacks. Naturally, that eliminates the majority of what some folks consider humorous.

Since we’re not after the college crowd from across town, nobody looks twice when you put your elbows on the table. Plenty of Good Food! Cheap! as the sign says in the window.

Then Miss Minnie gets offended when Tan licks his knife. Go figure.

I stand up the catsup packages on their ends like I’m about to shuffle a deck of cards, hear a chop, chop sound from the kitchen. Today is Tuesday. That’s Danny dicing onions for the liver special. As I fold the shutters across the pass-thru to keep the smell back there, I watch Penny in the mirror over the counter, the gold half-heart dangling, innocent as a cross around her neck. She blows on her coffee, taps a thumbnail idly on the counter and looks around like she’s surveying the place.

I’m tempted to tell her, if you’re looking for fancy, you won’t find it here. None of those earth colors or deep dark booths for Jack. He took over the Feed Room when Jess, his mother, died. I think he’d have been satisfied to close it down but everybody made such a fuss. He gives me a free hand with the running of it.

Even though this is a no-frills place, I try to keep it bright. The tables are big enough for elbowroom and space left over in the center for a potted plant, alive and mainly well. I have the knack. Crystal, my granddaughter, says, “Grandma, you can make a pencil grow.” I’ve sprinkled stout hanging baskets about but nothing to block the sun from coming sharp in the windows. This leaves the Chinese restaurant across the street in full sight. Green-striped shutters cover a good portion of the dragon that curls in splashy reds and blacks out front.

The Red Dragon has been in decline since the bus boy disappeared with the rice cooker and Foo Wong served Minute Rice to the lunch crowd. Something sacrilegious about that. People put it in the same category as the incident with Tan and the catsup bottle. Still, folks on our side of town keep coming to The Feed Room. Either they don’t care or being American is easier to forgive.

As I top off Penny’s cup of coffee now, she pushes her thick hair, which glistens like an oil slick, back from her face and I get a view of her busy ears. I see nine — that’s nine, I count them myself — earrings dangling from each ear. They dance against her cheek, each earring a string of beads in bright turquoise, rusty terra cotta, shades of copper like wet sand. I like them, picture all those southwestern colors sweeping against my cheek, each ear a little piece of the Painted Desert.

Then I brush back a strand of my own hair, a faded-out cork shade that I got from my mama. I finger one of my tiny stud earrings and know I lack the courage for anything fancier. Besides Samson would have a fit.

Penny is here early today, and by herself. That’s unusual. Recently she and Merle moved to town and opened a paint and body shop in the old Goodwill Store on the corner of Vine. Ordinarily they close at five, then the two of them hightail it here in time for the blue plate.

Nobody knows much about where they came from. We don’t ask, figure if we’re supposed to know, we’ll find out without having to. Lots of speculation though. They seem honest, did a good job repairing Franklin Pearson’s Toyota when he got rear-ended out by the stockyard.

Penny’s gaze lights on Silo now and sticks, not moving. I can tell she’s spotted his nose and is trying to get past it. I want to say, honey, I know the feeling.

Silo looks like any ordinary guy with thinning hair except for that nose. It stretches out in front of him like a plank of flounder with freckles, a pale undernourished flounder with sprinkles of black pepper down both sides. The first time I saw him, his nose stopped me, too. I said to myself, if I was his mama, I don’t care how much it cost, the nose would have had to go, even if it meant paying it off on the installment plan.

For a while after he closed his duct-sucking business, Silo worked Layman and Central as a school-crossing guard. At rush hour, that nose backed up traffic as far as the eye could see. It still throws strangers for a loop, but once the initial shock wore off it didn’t bother me in the least. Goes to show how you can get past anything once you get to know a person.

The whole time Penny stares at him, Silo doesn’t look up. He’s busy trying to keep Lucky out of sight, which is wasted effort. Like I don’t know the dumb dog is there.

With a wet rag, I swipe at a stubborn spot of yellow caked hard on the counter. When it doesn’t budge, I scrape at it with my fingernail. It’s rough, like cement. Mustard? Egg yolk? Finally it disappears. I catch sight of some crumbs, get rid of them, then feel along the underside of the counter for wads of gum, stuff people like Miss Minnie spot in a heartbeat.

Eventually, my eyes travel back to Penny and the necklace. It’s a fact that she doesn’t try to hide it. Of course, figuring out where the other half dangles is a no-brainer. The name Merle, engraved in sturdy block letters, stares from inside the half-heart, like it’s guarding the down shaft to a gold mine. Most everybody in town has the scoop on the situation. It’s not the kind of thing that’s seen much here in this part of Georgia, in a town as small as Clarkston, but they seem to have pulled it off.

Then I see Silo’s face. When he turns, spots Penny, his eyebrows shoot up, stay arched like they’re hooked on something overhead. I stand with my mouth half open, think how I’m mistaken about everybody in town knowing although Samson swears we know such things even when we don’t know we know. He says it’s just how much we let drift up into our minds at the time. I’m not buying it. I know Silo. He doesn’t have a clue.

I recognize the look on his face. It’s one I haven’t seen since Ruth died five years ago. He closed up like a fist then, sealed up that place in himself where those looks come from, like boarding up a house. Since then, he’s walked around, out of step with the world, his shoulders slumped, like something heavy is riding them, something he needs to apologize for.

In his grief, Silo’s life became divided into before Ruth and after Ruth. When he lost her, he forgot how the easy back-and-forth that never means much, but keeps people connected, works, too. I think this drove people away from him more than anything else.

I remember one day on his way out the door, Bert Thomas stopped beside Silo, who sat on his usual stool at the counter. He slung his arm across Silo’s shoulders. “It’s cloudy. Do you think we’ll get a rain shower today, Silo?”

No big deal. Right? Bert’s just making conversation. Right?

Silo looked up. “You mean outside?”

Bert’s arm fell from Silo’s shoulder. He stared like he’d dropped a link somewhere in the conversation but wasn’t sure which one. Finally he said, “Yeah, Silo. Outside.” He gave the shoulder a pat and stepped out the door, shaking his head.

After a while, people began to have business elsewhere as they passed his stool. Where before they’d acted like they wanted to help him grieve his loss, they took now to hurrying by without a word. Finally they stopped seeing him in his regular place at the end of the counter at all. They’d have noticed if he hadn’t been there but they stopped noticing that he was. Not that I blamed them. After his comment about the chicken soup, I felt like clamming up myself.

The morning this happened, I was rolling silverware, feeling perky, out to save the world, starting with Silo. “You’re looking a little peaked today,” I said to him. “Try some of Danny’s chicken soup. It’ll make you feel better. It’s good for you.”

He was quiet for a minute then, without an ounce of life in his voice, he said, “But not so good for the chicken.”

I took the silverware to the kitchen, finished rolling it back there.

He’d always been a fool about Lucky. After everybody took to leaving him to himself, he came to dote on her more than ever. He seemed to think if he let go of his dog, he’d lose his grip on life as well. Other than coming here for meals, his time was spent on his front porch with Lucky curled at his feet. The two of them, lively as doorstops, sat with their heads cocked to one side like they were listening in on something important, while his bug zapper sent moths and fireflies reeling into forever.

Suddenly, what Silo forgot in those years, he reinvents now in the time it takes him to scoot down the counter and straddle the stool next to Penny. His moves are smooth like he’s polished them. This surprises me. I’d have thought when he forgot what being alive was all about, the actions that went with it would go, too.

Now when he zeroes in on Penny, something hot and proud flashes between them. Quick as a jolt of electricity, I see the fever of life and loving rush back into him.

The fierce new spark in Penny’s eyes as she returns Silo’s look brings me up short. I marvel at how she got past his nose in record time.

I gaze through the plate glass window. It’s windy outside, as only Ground Hog Day in Clarkston is windy. Signs slap back and forth like they’re carrying on a conversation with each other.

If ever I’m tempted to intervene, to say, Silo, there’s something you need to know before you get in over your head, it’s now. The right words might make a difference. He and Ruth never had children so no offspring is here to say, Hey, Pop, I don’t think this is such a good idea.

Ruthie, as she was known back then, played tambourine in the church band. Silo took her out the first time in his daddy’s 1956 Nash with the fold-down leather seats, a tiny s in one of the back cushions where he’d carved his initial with his new pocketknife on a trip to the Cyclorama. When he parked on the dam at Cypress Pond, he opened the same knife and cut a Hershey Bar square down the middle.

“Take your pick,” he said in a deep solemn voice that only the summer before rang in the church choir as a shrill tenor. “I’ll be fair with you,” he told her and he’d done like he said, even though Ruth expected him to make something of himself on the scale of Jesus Christ or Herman Talmadge and never got over the fact that he didn’t.

“I never let my pride keep me from loving Ruth,” he said once, studying the coffee grounds in the bottom of his cup. “She was a shy woman. If I’d waited for her to say it, I might as well forget it. But when I told her, she’d reciprocate in more ways than one.”

Silo has the notion that anything come by too easily doesn’t stand for much.

In the mirror over the back counter now, I meet his eyes, read the look in them that says, Is this happening to me? Is it my turn again? I never knew you got but one.

So I don’t say a word. I whip a rag around and around the top of a sugar container. I shine until the stainless steel glistens bright as the sunlight that lays out tiny dots on the table tops next to the window, like a board set up for a game of Chinese checkers. At a corner table, Bert Thomas and his brother, Ray, polish off the last of their grits and eggs. Then they take their leave, each wearing a shirt with Thomas Lumber Company stitched across the back.

As I watch them, I think that to the outside world we probably don’t seem like much, but in the Feed Room, we’re real important to each other. We know the things to take note of, the things to overlook. I let Lucky steal food off the tables when nobody is around. Is it my fault she gets too brazen? We don’t ask Tan to leave when he sticks his case knife in the bottle of tomato catsup—we change to packages.

I’m about to carry Ray and John’s dirty dishes into the kitchen when Merle pulls up out front. I stop with my hands still full and dart a glance toward Silo and Penny. They sit with their heads close together at the counter.

I get a tight queasy feeling in my stomach as I watch Merle’s hands with their fingers stout down to the nails, ease the door of the pick-up open with a groan outside. Then her head appears, big and round as a full moon, topped by a duckbill cap tilted to one side. She takes off the cap, runs her fingers through her hair. It’s baby-thin and the wind tosses it about in ruffs that leave me staring at a bare scalp. She’s heavyset with arms that are thick and hefty. Slapping her cap back on, she holds the bill, anchors the back with the other hand and rocks the cap back and forth, resettling it firmly on her head.

I strain forward, search for a glimpse but can’t see it. Still, I know it’s there—the necklace with the half heart dangling in the valley beneath her plaid flannel shirt. The tight feeling in my stomach turns to a flutter like a humming bird is inside batting its wings to beat the band when Merle hitches up her jeans and slams the door to the pick-up.

From here, Penny and Silo look like a closed unit, whispering at the counter. Penny’s face is slightly flushed. When she breathes, I see her chest go up and down. She takes short little hyperventilating gasps, like the spider plant swinging overhead is using up all the air in the room.

Setting the dirty dishes on the counter, I straighten the napkins into a tidy pile. Suddenly it seems real important that I keep them precision neat. One side of me wants to melt into a puddle and disappear behind the counter while the other, the side that wouldn’t miss this for the world.

When I see Merle bend low and shade her eyes from the glare to peep in the window, my toes curl inside my crepe soles. Whether she’s verifying what she already knows or just checking, I’m not sure. With her face to the glass, her eyes appear swimmy like she’s looking from the inside of a goldfish bowl. When she spots Penny, she stands up, parts the door and steps inside. As she crosses the room, I admire how she moves, bouncing lightly on the balls of her feet, her hips rolling easily, gliding like a well-oiled machine.

I’m studying her so hard, I jump when Danny drops something in the kitchen. Then I hear him running water. The sound, a curling noise, loops in and out like rain on a tin roof as it hits the bottom of a pot, splashes over into the sink.

Silo sits facing the door. Penny has her back to it, hasn’t seen Merle yet.

While she draws closer, I try to picture what Merle is seeing. A middle-aged man with a thunderous nose, balding, who spreads the half dozen hairs that are left out like a fan on top of his head and pretends he’s not. Nice dog curled at his feet, quiet, not bothering anybody.

When he sees Merle striding across the room, Silo looks up. He follows her with his eyes, curious, like he knows this has something to do with him but can’t figure out what.

Penny must have read this new look on his face. She turns. When she sees Merle, she sits up straighter, pushes away from the counter—from Silo. I see her switch gears, the flame in her eyes lowered like somebody’s closed a damper. She looks down at her hands where, all of a sudden, I see she’s giving her cuticles a fierce workout.

Try as hard as I might, I can’t take myself out of what’s going on here. That’s the thing about a small town. Stuff gets right in your face and stays there. For once, I can’t figure out what I’m supposed to take note of, what I’m supposed to overlook. So I fail miserably at closing my mind to the possibility of what’s coming next. Will Merle figure out what’s going on between Penny and Silo or will Silo spot their necklaces first? It’s a toss-up. So far, nobody’s said a word. I stick a cup on the counter for Merle, fill it with coffee, top off Silo and Penny’s, take what comfort I can from that.

Suddenly, as Merle nears the counter, her eyes glide past Silo like he’s not there. When her eyes lock onto Lucky, they light up like she’s won the lottery.

Amazed, I watch her bend down, scratch Lucky behind the ears.

“Hey, girl. What ya know? Pretty dog, pretty dog,” she says, snapping her fingers.

I come from behind the counter to make sure Lucky hasn’t been replaced by some dog I’m not familiar with. Sure enough, it’s her. She’s in a frenzy, trying to unwind from around the post while she wags her tail and licks Merle’s face at the same time. On her knees now, Merle stretches her neck, twisting her chin back and forth to escape Lucky’s tongue. When she finally quiets down, Merle glances at Silo. “Blue tick?”

He nods.

“Don’t think I’ve ever seen one with this coloring before. Brindle?”

He’s about to answer when Merle leans over to examine the shading on Lucky’s back. That’s when the half heart with the name Penny spelled out across it drops from Merle’s shirt and dangles like a neon sign in front of Silo’s face.

I take a deep breath and hold it. Now my stomach is throwing a fit. I picture two of those ulcer germs stationed on each side of it, chomping their way across to the center where they shake hands, congratulate themselves on winning the war.

Silo puts his coffee mug down in the saucer so carefully you’d think it had turned into a piece of fine china. Then he eases close for a better look. When his eyes fasten on that necklace, he blinks several times, fast and snappy, like he’s making sure they’re in focus. Then he leans back, cuts his eyes at Penny.

She fidgets on the stool, keeps her eyes lowered. She’s watching him but sneaks the looks from behind the curtain of hair that drapes half her face. Neither of them says a word while their eyes dodge each other and the air between them fills up with a painful silence thick as clam chowder.

Merle and Lucky are in the middle of the restaurant now, romping and playing like two kids. Merle’s cap flies off, lands behind a chair leg. She scrambles over to retrieve it with Lucky tugging at her shirtsleeve.

Silo sits still as a table lamp while he tries to digest what this means. I can see the pictures parading across his mind. When he finishes putting it together it’s his turn to pull away. I feel the fresh new life in him withering, shriveling as he closes into himself again, tight as a peach wrapped around its seed.

I’m tempted to reach across the counter and take his hand, hold onto it with all my might. I wanted to tell you, Silo, I really did. But I couldn’t. I’m sorry for that now. But don’t go back. Anything is better than that.

Then Penny lifts her head, looks straight at him. She runs the tip of her tongue across her bottom lip to moisten it. Then her face breaks out in a big grin, like everything is as normal as piecrust. She gives a soft chuckle and shakes her head. It’s like she’s saying, Hey, Silo. I didn’t mean to spring this on you but you were bound to find out sooner or later. So, now what?

I’m so busy watching Penny and Silo, I forget about Merle. When I notice her again, she’s stopped roughhousing with Lucky and leans back, resting on her heels, watching them, too.

Penny holds the grin longer than I could have under the circumstances. Silo doesn’t give an inch. He keeps her steady in his gaze, studies her like she’s just sprouted a second head and he’s curious about how she’s managed to do that.

By the time the grin finally drains from her face, Merle catches on. Leaving Lucky sitting on her haunches, she tucks in her shirttail, comes over to the counter where she drapes an arm over Penny’s shoulder. The way Merle does it, you’d think she’s just arrived and is tickled to be there. She nods at Silo. I can see her taking a new interest in him now.

For the first time, I feel like I need to jump in, so I come up with something really brilliant. “How about some coffee, Merle?” I reach for the coffeepot.

“Penny?” Merle raises an eyebrow.

Penny nods, the flush drained from her face along with the grin. “Maybe we just better go.”

“Whatever you say.”

Merle doesn’t stop to ask questions. She keeps her arm across Penny’s shoulder while she eases off the stool. The two of them head for the door. Silo sits, following them with his eyes.

I stand behind the counter with the coffeepot poised over Merle’s cup, like somebody has turned me off and neglected to turn me back on.

At the entrance, they stop. Merle glances back over her shoulder at Lucky who watches them from the center of the room. When the dog sees that Merle is leaving, she gives a feeble whine from deep inside her throat and looks back at Silo.

The dog is no favorite of mine, but I feel sorry for her now. She’s baffled by what’s going on.

They all have their eyes on Lucky. It’s like everybody is taking turns. First one, then another. Now, it’s Lucky’s turn. After a second, she figures this out. Giving Silo a sideglance, she trots across the floor, her nails making a click, click sound on the tile floor. She wags her tail, licks Merle’s hand. Merle bends, pats her on the head.

“Sit, pretty girl,” she says with a twinge of a smile. Lucky wheels, props on her haunches between Merle and Penny. Silhouetted in the doorway, all three of them face the counter, their gaze fixed on Silo. Now it’s his turn.

Silo’s mouth drops open. He can’t believe what he’s seeing. Neither can I.

Finally, he closes his mouth and leans against the counter, his face drained of every expression I can read.

Then like she knows it’s Silo’s move but she’s decided to go out of turn, Merle leans over, whispers in Penny’s ear.

Penny glances up at her in surprise. Merle nods.

In a nonchalant tone, like she’s asking him to pass the salt, Penny says, “Coming, Silo?”

Even though I know full well the Feed Room is empty but for us—and thank God for that—I look around frantically for somebody to testify to this. For a second, I feel like dragging Danny out of the kitchen. But what’s going on here is between these three people and a hound named Lucky. It doesn’t need witnesses because it’s nobody’s business but their own. Still, I catch myself holding my breath.

I see Silo struggling. I know he’s trying to reconcile in his mind how some things in life stay true no matter how much we wish they’d be otherwise. He shifts on the stool, looks across the counter at me. I’m careful to keep a neutral face.

When he slides off the leather seat and squares his shoulders, I know he’s made up his mind. As he crosses the room, Lucky’s wagging tail pounds up and down on the door behind her like she’s beating on a drum. I see Merle make a move to turn and push open the door for them. Suddenly she stops and glances at Silo. He reaches around her and slides it open. Stepping back, he stands, fine and manly, while she and Penny and Lucky go out ahead of him. Then with a swishing sound, the door closes behind them all.

I’m not sure how Silo will fit into Penny and Merle’s formula. Probably he doesn’t either. This is a leap for him. Who was it said, miracles come in an instant, not when they’re summoned, but of themselves—and to those who least expect them. I forget. But I do know one thing, Silo thinks a man is judged by his convictions and he’s always been true to his. That’s not something that’s likely to change.

Outside the wind, which had died down, picks up again. My eye catches on a stray piece of paper that skips past, dodging in and out between the parking meters like it’s playing tag with them. I try to remember if the ground hog could have seen his shadow today or not. I can’t remember. Samson will know.

Gathering up the dirty coffee mugs, I head for the kitchen so Danny can get them in the dishwasher. We’ll need them for the lunch crowd that’ll start pouring in any minute now.

Tags

Linda Dunlap

Linda Dunlap is a resident of Florida. Her writing has appeared in The Crescent Review, Calliope, and RE:AL. She is working on a novel called Digging Queen Esther’s Grave. (2000)