Outdoor Dramas

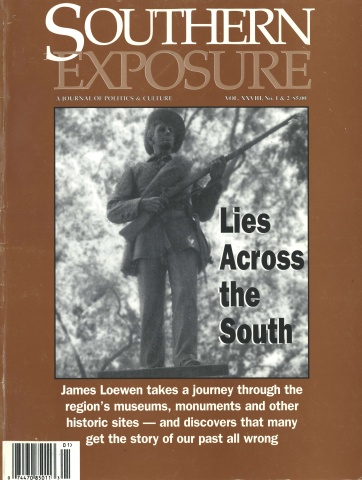

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 28 No. 1/2, "Lies Across the South." Find more from that issue here.

Southerners like to tell stories, and the more spectacular the story the better. Through outdoor dramas, Southern communities have found a way to tell their proudest tales with actors, music, dance, and special effects ranging from real floods to fireworks.

“The reason there are so many outdoor dramas in the South,” says Todd Lidh, director of communications for The Institute of Outdoor Drama based at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, “is that Southerners may have a greater attachment to the history of ‘my town.’ Outdoor dramas speak to the feeling of who shaped our beliefs and affected our history.”

The first American Outdoor Historical Symphonic Dramas, as they are officially known, were performed on the coast of North Carolina. The citizens of Manteo worked with playwright Paul Green to develop a drama to commemorate the 350th birthday of Virginia Dare. Performed on the historic site of Roanoke Island and only scheduled to run one year, “The Lost Colony” attracted President Franklin Roosevelt and hundreds of visitors, who had to get to it by ferry. It has been in production ever since, and played a major role in bringing tourism and development to the Outer Banks of North Carolina.

Interest in outdoor drama spread as more and more people saw “The Lost Colony.” Green became a consultant to groups starting their own dramas, and by the 1960’s, The Institute of Outdoor Drama had evolved at UNC-Chapel Hill to study and support outdoor drama. Today, there are over 100 outdoor dramas in 34 states with annual attendance of 2.5 million. The South still takes the lead; 16 dramas are performed in North Carolina, 13 in Texas, and more are scattered across Kentucky, Georgia, and Virginia.

What makes outdoor dramas unique, says Lidh, is the combination of music, spectacle, and history. Performed outside in the evening with either live or piped music, many dramas include “spectacles” that are impossible for indoor theater, such as fireworks, floods, simulated lightning strikes, horses, and trees. The stories seem more immediate and alive because they are performed on or near the site where the event happened.

Outdoor drama themes range from overcoming adversity and fighting oppression to individuals uniting in a cause. According to Lidh, the longest running dramas tell the bad as well as the good, of crimes and massacres as well as proud moments. In “The Floyd Collins Story,” a Kentucky farmer is trapped in a cave for two weeks while a nationwide effort is launched to free him. Snow Camp, NC’s “The Sword of Peace” and “Pathway to Freedom” tell the story of Quakers and the slaves they freed in the underground railroad, while “Unto these Hills” describes the Cherokee Indians’ forced removal from North Carolina.

“Incident at Looney’s Tavern,” performed summer evenings in Double Springs, Alabama, tells of poor Winston County hill people who didn’t care about preserving slavery and just wanted to be left alone during the Civil War. They decided if Alabama could secede from the Union, Winston County could secede from Alabama. They met at Looney’s Tavern to resolve to become a “free state.” Looney’s Tavern Productions stages the outdoor musical “within a stone’s throw” of the original tavern site, using singing, dancing, humor, and fireworks to bring the story to life.

The stories outdoor dramas tell make their communities proud, but so do the dramas themselves. “Local families bring their out-of-town visitors to see ‘Incident at Looney’s Tavern,’ and a lot of our resources and manpower come from volunteers,” says Pat Taylor, Public Relations Manager for Looney’s Tavern Productions. “Local folks are proud we’re here.”

Tags

Mary Lee Kerr

Mary Lee Kerr is a freelance writer and editor who lives in Chapel Hill, NC. (2000)

Mary Lee Kerr writes “Still the South” from Carrboro, North Carolina. (1999)