This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 28 No. 1/2, "Lies Across the South." Find more from that issue here.

Virtually nothing would convince the city leaders of Knoxville, Tennessee, that the city’s police department (KPD) had a serious problem. Not calls for reform by the city’s NAACP chapter and the progressive religious community. Not the deaths of four men, three of them black, at the hands of KPD officers in the span of seven months. Nor the revelation that police had lied about finding cocaine in the car of one of the victims.

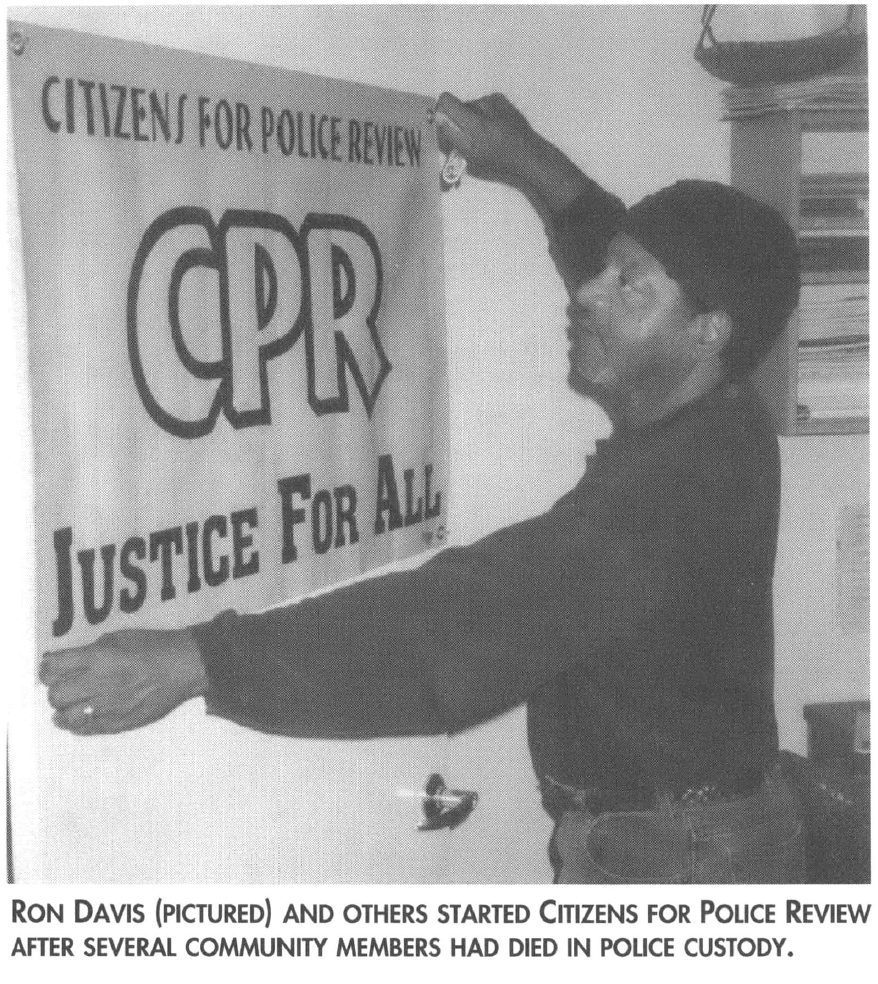

It would finally take a city brought to the brink of violent backlash to get the mayor, police chief, and city council to consider change. Indeed, Ron Davis, of the grassroots group Citizens for Police Review (CPR), still marvels at the intensity of the community’s response to police brutality: “We had no idea the flame we were trying to keep lit would become a raging fire so quickly.”

A Rising Tide of Brutality

The drama dates back to the early 1990s, when the KPD’s public relations arm began saturating the Knoxville media with drug-bust stories. At the same time, the department touted a steadily decreasing crime rate and national recognition of its community policing programs. But going largely unnoticed were skyrocketing complaints of police misconduct and an increased incidence of unsolved hate crimes.

As it became apparent that police brutality complaints made to the KPD’s Internal Affairs Unit (IAU) were rarely upheld, complainants began turning to the Knoxville chapter of the NAACP.

“We documented about twenty cases of brutality and harassment over two to three years,” says chapter president Dewey Roberts, “But IAU would never sustain them, even with our own investigations and people hospitalized because of police attacks.”

The NAACP soon realized it did not have the capacity to handle the mushrooming number of complaints. At that point, the concept of an independent citizens’ police review board started making sense to Roberts’ group and others, as an alternative to the police policing themselves.

The NAACP first petitioned the Knoxville City Council to establish a review board in 1993. Minimal organized support and vehement police opposition guaranteed the proposal only a short political life. As public attention focused on the issue, police misconduct decreased, but not for long.

By 1996, a series of town hall meetings in County Commissioner Diane Jordan’s inner city district were dominated by complaints of police harassment and violence. The year after, school teacher and videographer David Drews was working with Jordan, Roberts, and neighborhood activists to document stories of alleged police brutality.

“It was frustrating,” says Drews. “So many were coming out of the woodwork with their stories that I was running out of money for videotape.” Their work eventually resulted in the renewal of calls for a review board, and the establishment of Citizens for Police Review, or CPR.

Fanning the Flames

As CPR was born in the inner city, another anti-racist effort was in its embryonic stages across town. The ad hoc Faith Committee for the Prevention of Hate Crimes was a group of mostly white members of Knoxville’s tiny assortment of progressive churches. Frustrated that the only organized response to cross-burnings seemed to be candlelight vigils, the group sought more pro-active, preventative measures. The committee focused on the KPD, since its dismal record on solving hate crimes seemed to encourage racists.

It did not take long for the black and white groups to discover each other. “It was after we talked with CPR folks that we realized police might be guilty of hate crimes themselves, through acts of brutality,” said Margaret Beebe, whose fundraising efforts for the Faith Committee were soon transferred to CPR. The Faith Committee soon disbanded to become CPR members, willingly — but not easily — taking a back seat to African-American leadership.

The death of Juan Daniels in October, 1997, thrust the fledgling alliance into a firestorm of controversy. Daniels, reportedly drunk and suicidal, was shot nine times by two white policemen in his basement, after (police claim) he lunged at them with a knife. In the standoff leading up to his death, Daniels, a 25-year-old African American, asked to speak to several people, including his mental health case worker (now a CPR member), but was only allowed to talk to his roommate.

The incident occurred within four months of the shooting of James Woodfin, an African American who was shot with a twelve gauge shotgun in the bathroom of his public housing apartment by a KPD officer, who was trying to serve him a misdemeanor warrant.

The October city council meeting suspended its entire agenda when 400 angry people responded to the Daniels killing by showing up to demand a police review board.

Call for Action

Mayor Victor Ashe responded by ordering video cameras installed in every squad car, but insisted a review board was a bad idea. The mayor also appointed a task force to look at other ways to get citizen input. The task force meetings proved to be largely dominated by KPD Chief Phil Keith’s reports on decreased crime rates. When asked about a review board, the Chief responded, “We already have police review. It’s called a Grand Jury.”

The task force had only met four times before the death of Andre Stenson rendered it moot. On January 9, 1998, the newlywed father and chef at Calhoun’s restaurant died after fleeing a traffic stop and struggling with four white police officers. Having recently served jail time for burglary, he may have panicked about violating parole for driving without a license. KPD public information officer Foster Arnett Jr., speculated that Stenson died from a cocaine-induced heart attack, and claimed that crack had been found in his car. The medical examiner later ruled that he had died of a rare heart condition, triggered by the stress and extreme exertion of the incident. Cocaine tests were negative.

The news quickly spread through the inner city that the police had killed another black man. The more police denied their responsibility in relentless television interviews, the edgier the mood became on the street. In a hastily called press conference, a worried-looking State Representative Joe Armstrong pleaded, “We have heard reports that retaliatory action is going to happen, and we urge all of our constituents to remain calm.”

Within 24 hours African-American ministers were on every station, calling for a massive turnout at the next city council meeting, once again to demand a police review board. With this call repeated Sunday morning on the Knoxville News-Sentinel’s front page, as well as at most African-American church services, the 500-seat council chamber was standing-room-only for the first time in its history. Cries of “Justice!” rang out amid seven hours of calls for a review board and for the ouster of Chief Keith. Some public threats of armed retaliation expressed that evening were rebuffed by ministers and CPR members.

The following day, police spokesman Arnett recanted his claim that cocaine had been found in Andre Stenson’s car. Arnett said an officer, whose name he forgot, told him a police dog detected drugs in the car. Arnett’s superiors said he failed to “clarify” the information, and he was given a written reprimand.

Within 48 hours, Mayor Ashe and Chief Keith announced their decision to support a police review board.

“Watching the Watchdog”

Since the mayor appointed the Police Advisory and Review Commission (PARC) in 1998, the pace and intensity of KPD abuse has again subsided. But the Knoxville organizers who worked on police accountability before it was front page news are forced to wonder whether theirs was a pyrrhic victory.

“No doubt we needed something like PARC,” says CPR’s Ron Davis. “But we may be getting lulled into complacency. We don’t see near the numbers of folks at CPR meetings that were there before we had PARC, yet excessive force complaints still look like a waste of time.”

All the police who were involved in the deaths were exonerated, and with less than one percent of excessive force complaints leading to disciplinary action, the KPD is far behind the national average of 12-15 percent.

CPR is slowly adjusting to its new role, which some members describe as “watching the watchdog.” The group usually has at least one of its representatives at each quarterly public meeting of the PARC. After a year of slow action, CPR is demanding the PARC deal with several issues right away, including what is really behind the low rate of disciplinary action, identifying police who are repeat offenders, and verifying persistent reports that at least one patrolman is a member of a hate group.

Another source of tension comes from the makeup of the PARC. With a retired FBI agent (a white male) chairing a police review commission which includes the past president of the University of Tennessee (white male), two female lawyers (one white; one black), two male ministers (one white; one black), and one black male school teacher, most of them have not avoided being perceived as out of touch with the typical victims of police brutality.

While CPR tries to make the most of the public forum that the PARC provides, its members continue to look for better models of police accountability in other communities, especially where community organizing engages citizens to create ways to truly keep the peace with police.

“We can’t afford any more public relations campaigns,” Ron Davis warns. “If all this turns out to be window dressing, I don’t like the odds of keeping the peace when the next atrocity happens.”

Tags

Rick Held

Rick Held is a journalist and activist based in Knoxville, Tennessee. (2000)

Rick Held is a writer in Knoxville, Tennessee. Ruben Solis, coordinator of the Border Campaign for the Southwest Network for Environmental and Economic Justice, contributed to this article. (1993)