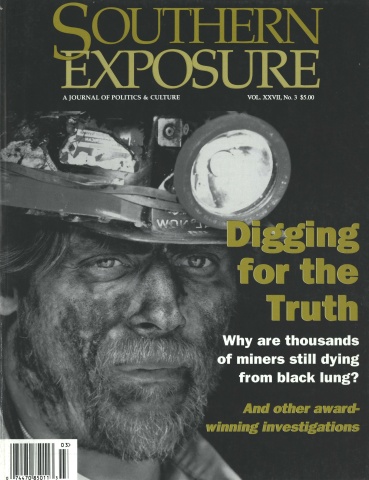

This article first appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 27 No. 3, "Digging for the Truth." Find more from that issue here.

“I told Drenda we’d come over tonight, but I’d have to check with you to be sure you didn’t have plans in the works,” I said as I handed Roy a bourbon and Coke.

“Thanks, “ he said right before he took a big swig of his drink. “Billy’s coming over.”

“That’s fine, Billy can go with us over to Drenda’s.”

“But Billy isn’t coming over here to go to Drenda’s. I don’t think he would want to go. They don’t really know each other.”

“So?” I asked.

“So what?”

“So what if they don’t know each other. We’ll have a few drinks. Drenda’s boyfriend will be there, they live together. I don’t see a problem.”

“You know what I mean, Cindy.”

“I know what you mean? Sure Roy, I know what you mean. Oh dear, what if your buddies found out you spent Friday evening with a black couple? Would your reputation as a good ol’ boy be ruined? Would they make you read a book for punishment? I never thought it ran that deep.”

That’s how it started. A nice, simple Friday evening normally spent relaxing, letting the week’s crust slowly melt away, was suddenly a power struggle. Though I’m not sure if power struggle is really the correct term. A difference of opinion? A collision of egos? A man/woman thing?

Roy and I were at it again. Arguing. Giving our sides. I won’t lie and say this is how it’s always been. At first, when we started dating in college, I have to admit I went along with everything he said. Whatever he wanted to do, I did. “Let’s go to Bill’s party.” We did. “Let’s not go to Pam’s party.” We didn’t. “Let’s go to Florida this weekend.” We went to Florida.

But drip by drip, things changed. I started sticking up for myself, voicing my views. Why? Where did this come from? Hard to say really. I had a girlfriend who was very strong willed, some might call her a feminist, though in the South that’s blasphemy.

Mary was her name. She was from Wetumpka, a small town not far from Montgomery. I met her the spring of my junior year through a mutual friend, Barbara, who lived in the same apartment complex as me, a few blocks from the campus of the University of Alabama. Mary didn’t go to school, she just drove over to Tuscaloosa to visit Barbara every now and then.

Barbara was kind of a free spirit, a little bit of a hippy (faded jeans, a purple VW bug, the Beatles, pot, lots of boyfriends, long straight blond hair), but she didn’t hold nothing to Mary. Mary shaved her head, a lot of people thought she had cancer. She never wore a bra; though her breasts weren’t huge, they were big enough to make a point. She never missed the opportunity to gnaw on people’s heads when they made sexist remarks.

More than once she gave it to Roy. “I’m so glad you decided to attend the party. You’re such a special guy to allow Cindy to come here.” Roy, needless to say, didn’t particularly enjoy Mary’s company, though he did find her spunk interesting. Mary opened up a new world for me, showed me a different lens to see the world. No longer did I stand by my man.

I felt comfortable with Mary’s admonitions, which explains my position on this Friday night. Why shouldn’t I go over to my friend’s house on Friday night? Drenda was black. We were white. We lived in Dothan, Alabama. South Alabama. Not just the heart of Dixie, you’re at one of the valves. I’m not crazy, I know the implications to all that.

“I wish I was in the land of cotton, old times there are not forgotten.” George Wallace. Little George. In the doorway at the U of A. Though over thirty years ago, the fires still smolder. Fire bombing Freedom Riders. Rosa Parks causing chaos because she wanted to sit down. Bulldog Connor. To Kill a Mockingbird. These people believe there are differences. DIFFERENCES. Keep to your own, what you know.

Nothing more was said on the subject for the next hour as we went through the routines of dinner and showering. As always, when we disagree, our positions were quickly put forth, then a sudden retreat on both sides for a thorough analysis of each move. The opposing argument would be thoroughly combed for weaknesses. Any slight break in the enemy line would be exploited for maximum gain. Even a misused word or a mispronunciation was quickly turned onto the opposition.

A silly game? Without question. But through our five years of marriage we had managed to mold our confrontations into a manageable battle. We did not fire nuclear missiles at the first instance of provocation like some couples will do. No shouting matches, no slamming of doors. I had heard of husbands screaming at wives because she “didn’t have the meal cooked when he came home from work,” “didn’t want to stay home on Friday night while he went out with the boys,” or “wanted him to keep the baby while she went to the hospital to see a sick friend.”

We were exempt from that lunacy. Rarely did we go to bed with our differences. Neither were we a couple to pretend that things were smooth at all times. Whenever I heard someone exclaim, “Oh, we never fight. I don’t think we’ve even had an argument,” I have this teeth-clenching desire to say, “You are a psychopath. You’re either lying to me or lying to yourself. Disagreements, conflicts, arguments are part of the human condition, you idiot.”

I finished a small portion of the taco pie I had prepared when I got home from my librarian job. I’d been working there ever since I had graduated from Alabama five years ago with a degree in Library Science. Roy had been working at my uncle’s accounting firm for the same amount of time. We met at the University when we were sophomores and became engaged a few months before we graduated. Dothan’s my hometown. Roy’s from Scottsboro.

Nothing special in our brief history, except I had an abortion our junior year. It was a close call. Roy wasn’t too sure about taking that way out, but I persisted and he eventually agreed, for whatever that’s worth. I never did really think about what would have happened if he had said no to it. I think he understood we weren’t ready to be parents, so it wasn’t a matter of who was going to get their way.

I got up from the kitchen table, walked over to the sink and cleaned my plate, then I made myself a bourbon and coke. Roy sat there at the table reading the paper. I stood at the counter sipping my drink, eyeing Roy.

Finally, I said I was going to take a shower. I had hardly spoken a word during dinner. As I mentioned earlier, everything was being weighed for effect. Silence during the meal was like the silence of a chess match. Keep the emotions at an even keel, let logic and reason have the upper hand. Our confrontations many times followed no pattern. A strategy would help, but could just as easily be utterly useless.

Which brought me to my sad state. My peaceful, easygoing Friday night was now gone. The picnic plans were over. Though acceptance brings its own tranquility, I now braced for a possible tumultuous confrontation.

I quickly bathed and dressed. There would be no whining about me not being ready. Show him I was prepared to leave. When I walked into the den. Roy was lying on the couch with his shoes off listening to a Steve Miller CD. He was digging in, making a stand.

“I am so worn out. What a week,” he said while rubbing his face with both hands.

“Me too. It will be good to get out and relax.”

“I guess I need to grab a shower before Billy gets here.”

“Go ahead and jump in, you’ll feel a lot better.”

Roy was bathing when Billy arrived. He had tried to quickly quell the storm as he readied for his bath, but I had my mind made up. He had asked me if I couldn’t call Drenda and cancel, tell her we’d make it another time. “I’m just not up to going out tonight,” he said.

He was thinking a retreat from the racial aspect would soften my tone. He was standing naked in front of the bathroom mirror when I told him, “I’m going to Drenda’s with or without you.”

Silently, he slowly stepped into the shower. A shower is one of the cocoons of meditation, I find it easy to sink into reflection and contemplation. Maybe it’s the running water, which seems to always make you feel at ease.

I knew he would run through his possible choices of recourse. What came to mind first was the obvious: “Well, just go on without me. I’ll just stay here with Billy and enjoy my Friday evening at home.” A strong reply. A manly reply. A reply that I would bludgeon him with Saturday morning.

I’m sure he thought of playing the ace of race cards: “Billy is an extreme racist, Baby, and he’s liable to cause an ugly scene at Drendra’s.” Miles from probable, but who knows? An instant save if I bit, though Billy would be left dancing the racist tango. I knew a facetious interpretation would just add thickness to my armor. “Ha, ha, boys.”

Sudden illness, drunkeness, Drenda cancelling, all went through his mind I’m sure, but his brainstorming shower was halted when I walked into the bathroom and said, “Roy, Billy is here. I’m leaving in 45 minutes.”

I was confident I had him by the short hairs. Not only was he working with the “with or without you” ultimatum, now there was a time line. He quickly finished bathing, dried off, and dressed.

“Hey, you made it through another week,” said Roy as he walked into the den. Billy was sitting on the couch, a small sack with a six pack of beer was on the floor by his feet. He was drinking a bottle of beer.

“Barely. Another day with that bur head would have sent me over the edge.”

“Uh, oh.”

“What’s the uh, oh, for?” Billy asked.

“Well, Cindy has made plans for us to go over to her friend Drenda’s place. Drenda is black, Mr. Archie Bunker.”

“Big deal.”

“See, I told you Billy wouldn’t have a problem with it,” I said while sitting on the other side of the room in an easy chair facing Billy.

“Sure, I don’t have a problem going to a spear chucker’s house.”

Roy started laughing. “You’re crazy, man. You better watch it. Cindy’ll cut your heart out.”

“If you really feel that way, Billy, I don’t want you going over there,” I said.

“I’m only kidding. So what, your friend is black. I like eating fried chicken.”

Roy chuckled and shook his head.

“Billy Dickinson!” I said.

“Cindy, you know I’m only playing. Who is this Drenda anyway?”

“She works with Cindy at the library. There’s one more thing you should know, her boyfriend will be there,” Roy said.

“I’ve only known her a couple of weeks. She just started working at the library. She and her boyfriend just moved up from Orlando. We kinda clicked from the moment we met. She’s a nice person.”

Billy gave Roy a quick wink. “Why are we arguing over this? If we’re going over to this Drenda’s place, then let’s go. Where does she live?” asked Billy.

“Over on the west side of the circle, in those new apartments. Pine View, Pine Crest, something like that. It’s no big rush, I told her we’d be over around 7:30 so we’ve still got about 30 minutes.”

We drank beer, talked about the Alabama-LSU football game the next night in Baton Rouge, and how the rich controlled the world, but we let the race issue just dangle out in front of us. Like a pinata filled with rotting potatoes, each of us saw it, but no one wanted to touch it.

I was reminded of what a good friend of mine said in high school. Danny Jackson was black and the star halfback on the football team. One afternoon after cheerleading practice a few of us were sitting around talking about racism when some of the football players stopped by to talk and look at our legs in short shorts. The team had just finished practice. Danny jumped right in, which didn’t surprise me since he had dated a few white girls, even asked me out once, but I wasn’t ready to fight that war. He said most white folks treated race like a bad dog. They keep it in the back, but they’re quick to bring it out when needed. At the time I just laughed, though I’m sure he had a few scars from several nasty bites.

Roy looked over at me as he laughed at Billy’s jokes. I figured Roy had decided to suffer through the night for the sake of using his compliance for a trump card later down the road.

A little before 7:30 we finished our beers and left our house. We drove over to Drenda’s in Billy’s ’76 white Cadillac convertible. “Shouldn’t we stop and get a watermelon,” said Billy.

“Don’t you start that,” I said. “Y’all have got to promise me you’ll behave. You cannot say things like that over here. You both know better. Drenda is a friend and I don’t want anything like that said.”

The top was down, Billy was driving, but all three of us were sitting in the front seat. I was sitting in the middle, but there was plenty of room to spare. Billy loved big cars. He had a natural inclination to bigness. He was fond of big dinners, big tv’s, big drinks, and most of all big women. Not husky, chunky or even chubby women, but big women. He was very particular. His taste didn’t include huge women, circus women, women who could whip his butt, but women, as he told me one morning, “who were born big.”

He had come up to visit Roy in Tuscaloosa during the fall of our senior year. Alabama was playing Tennessee at home that weekend. I was ordering a beer at the bar in the club we were in that Friday night when I looked over and saw Billy waving at me as he walked out the door with one of his big women. The next morning I wanted to get to the heart of his big woman desire, so I asked him.

“What I mean by born big is I don’t like average size women who have put on lots of weight, but rather a big person who isn’t real fat. In other words, even if they tried to get thin they couldn’t. They’re just big, real thick people. Maybe that’s really it. They’re naturally big. A person who is really fat isn’t really a big person, unless of course they’re big and fat which is a sad sight to see. Those people are like Great Danes, they die early, too much for the heart. Those poor things never have a chance. It’s the heart, you always gotta think of the heart. Most fat people are average size with lots of fat. Take me, I’m a big person. I’m not a skinny fellow, but I don’t have a whole lota fat. I’m big like my momma and daddy.”

Roy nodded his head. “I will be a gentleman of the highest order. You have my word.”

“Billy?” I asked as I looked over at him.

“You’re taking this much too serious. I do have a little class.”

“You do? I’ve never seen it,” Roy said.

“Oh yeah, remember that time I threw up on the bar at Cooter’s. I cleaned it up myself. You tell me that didn’t take some class.”

“That’s true, that was a classy move. Most people would have felt shame and left.”

“I’m a classy guy.” Billy finished off another beer and let out a bullfrog burp.

“Do you think we should stop and get some beer?” Roy asked.

“Perhaps wine would be more appropriate, old chum,” Billy said in a strained British accent. “Shall I stop and purchase a half gallon of Mad Dog? I’ve heard this is a very good month.”

“Yes, William, Mad Dog or a fine malt liquor would more than suffice,” Roy said.

“I know you two are playing and part of it is to get me riled, but I’m begging you to be civil over here. If you don’t think you can then let’s just turn around and go home,” I said.

“Victory! Turn this beast around,” Roy said.

Billy turned into a plaza.

“I’m kidding. Don’t turn around, man. Everything’ll be fine. We’ll have a nice evening over there.”

“I’m not turning around. I’m stopping at the grocery store to get some beer.”

“Why didn’t you bring your beer?” I asked.

“What beer? We drank it all.”

“I’ll go in and get some good beer and then we’ll go over to Drenda’s for a nice, pleasant evening. I promise. The night will be a model of civility and fellowship,” said Roy.

And that’s the way we left it, at least for the next few minutes. Roy bought the beer, then we drove over to Drenda’s. As we got out of the car to walk to the apartment I uttered a sentence without really thinking about it. The words were so foreign coming from my mouth that I thought someone else had spoken them.

I said, “All I want is peace.” Right out of the blue. I would expect Mother Theresa to say such a thing. Or perhaps one of the leaders in the Middle East after a bomb has ripped apart a couple of dozen people in a bus. Maybe any citizen living through the pains of a civil war would utter such a plea. But a young woman in Dothan, Alabama, on an October Friday night? I started to say something else, at least address these words, clarify their meaning, but I said nothing. I was at a loss. I didn’t know what to say.

Drenda’s apartment was located on the second floor of a complex that consisted of four buildings built in a square with parking spaces on the exterior, next to the buildings. A small pool was located in the center of the courtyard. I knocked on the door while Roy and Billy stood on each side of me.

Drenda opened the door, hugged me, asked us in where introductions were made just inside a den. She told us Howard was just getting out of the shower and would join us in a few minutes.

After the brief formalities, she asked us to sit, took the beer from Billy and then handed us each one before she left the room to place them in the refrigerator. The three of us sat on the couch with me in the middle.

When Drenda walked away I took a sip of my beer and looked at Billy. He did not return the look. There was no raising of the eyebrows, no devilish grin, not the least hint of a smirk.

I then looked at Roy. He was looking at me. I expected a look of disdain. My “All I want is peace” kept playing in my mind as if on a looped tape.

Again, from nowhere, questions unfolded. Were we at the end? Too chaotic? Too conflictive? Were we just too different? Our worlds much too far apart, the chasm far greater than I had at first believed?

From a doorway across the room walked in a young man. A zebra walking into the room would not have startled me any more than this man. His skin was as white as Drenda’s was black. The dynamics of the battle had dramatically changed. I was off balance as if the world had suddenly tilted. He walked up to coffee table and extended his right hand.

“Good evening, I’m Howard. You must be Cindy. Drenda’s told me a lot about you.”

“Nice to meet you, Howard. All good I hope. This is my husband, Roy.”

Roy shook Howard’s hand. “Nice to meet you, Howard.”

“And this is a friend of ours, Billy.”

“How you doing, Billy.”

“Good to meet you, Howard.”

As we finished shaking hands Drenda walked back into the den from the kitchen with a tray of broccoli, mushrooms, sliced carrots and peppers surrounding a bowl of dip. Suddenly, there we were. I looked at Roy, hoping for a read. Nothing. I sat there with a pain inducing smile.

“It’s a beautiful night, isn’t it?” said Drenda as she placed the tray on the coffee table in front of us.

“It’s gorgeous outside. There’s just a tinge of coolness in the air. We rode over here in Billy’s Cadillac convertible. I wasn’t cold at all. It just felt refreshing,” I said as I grabbed a piece of broccoli and swirled it in the white dip.

From the corner of my eye I noticed Billy placing his hands on his knees, then he stood with what seemed an enormous effort. Everyone was looking at him. I didn’t know what he was going to do. I had known him for over five years and I fully understood the uncertainty of the moment.

He picked up his beer from the coffee table and raised it to his lips, draining the remaining half bottle of beer. I felt as if I was stepping into a muddy creek.

Without saying a word he walked in front of me and Roy on his way into the kitchen. I heard the refrigerator door open and close. Trying to ease the tension that had blanketed the room I said, “Billy likes to drink beer, especially on Friday night.”

He walked back into the den carrying an unopened bottle of beer, in front of us once again, but instead of stopping at the couch he walked to the front door, turned to Roy and said, “I need to get some fresh air. I’ll be back in a few.” He opened the door, walked out, and closed it as if trying not to wake a sleeping baby.

I didn’t look at Roy because I was fearful of what I would see. Instead, I looked at Drenda and Howard. They had sat on a loveseat on the other side of the coffee table. Howard was looking at the dip. I knew what was going through his mind. Another reaction. Another incident. How many times had he faced it. Swallowed it down with its razor edges and acrid flavor. Deep in his mind I knew he questioned it. Was it worth it? Drenda was looking at me with her beautiful brown eyes. No animosity. She didn’t even look uncomfortable. Her eyebrows tightened slightly when she said, “Is your friend going to be okay?” Seemingly sincerely concerned.

Her words poured through my head. I opened my mouth, but could not speak. My muscles went slack. I had never felt this way before. I looked at Drenda. “I’m not sure,” I said. Then I said, “The fresh air will do him some good.”

“Do you think it’s something in here? Is it too hot? Should I open a window?” Drenda asked.

“No, everything’s fine here. Really,” I said. “Don’t you think, Roy?”

He stood and walked over to the front door. Telepathically I begged him to sit down. Please sit down. He opened the door, then turned to face us.

“I’m with Billy, I just need a little fresh air.” I closed my eyes as the door slowly shut.