This article first appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 27 No. 3, "Digging for the Truth." Find more from that issue here.

The following article contains anti-Black racial slurs.

“This is not a monument to suffering. It is a memorial to hope,” says Maya Linn, designer of the Civil Rights Memorial in Montgomery, Alabama. On November 5, 1999, the memorial which commemorates the many lives lost during the movement, celebrates the 10th anniversary of its dedication.

On the memorial’s circular black granite table, forty names are braided in gold block letters. They form a circular timeline, beginning with the Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown vs. Board of Education decision declaring school segregation unconstitutional, and ending with the 1968 murder of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. — space has been left between the first and last entry to honor the names that have been lost or forgotten.

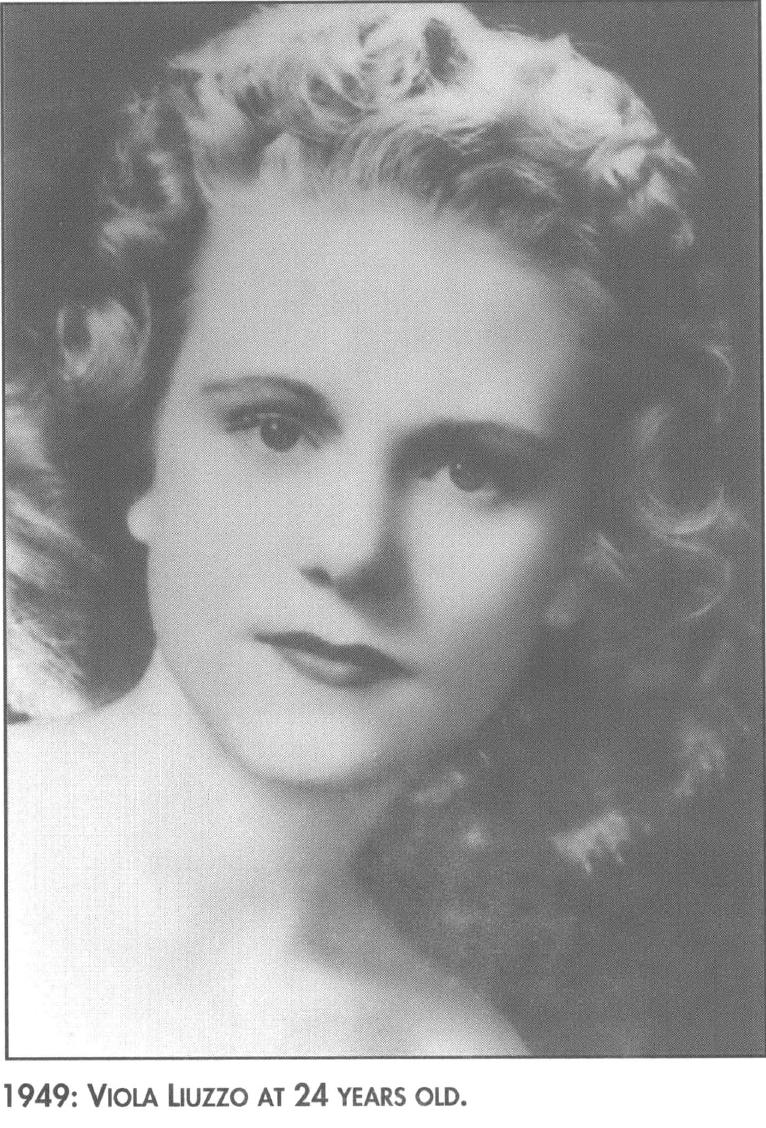

A decade ago, six thousand people had gathered on Washington Avenue, in front of the Southern Poverty Law Center, to dedicate the monument. Many were relatives, friends or comrades of the forty martyrs etched in stone: 29 black and seven white men; four young black girls killed in the 1963 Birmingham church bombing; and one white woman, whose story remains virtually unknown: Viola Gregg Liuzzo.

A red and white Impala full of angry Klansmen prowled the streets of Selma, Alabama, on the evening of March 25, 1965. The Voting Rights March had ended that afternoon, and federal troops were everywhere. Frustrated by the tight security, the Klansmen decided to return to Montgomery. Maybe they could provoke some trouble there.

Turning onto Water Avenue, they spotted a white woman in a car with a black man stopped at a traffic light. Viola Liuzzo and Leroy Moton were also heading back to Montgomery, to pick up a group of marchers who were waiting to return to Selma.

“Will you look at that,” one of the Klansmen said. “They’re going to park someplace together. I’ll be a son of a bitch. Let’s take ’em.”

Weeks later, one of the Klansmen — Tommy Rowe — would tell a grand jury that they followed Mrs. Luizzo’s car along Highway 80 for the next twenty miles. When she realized she was being tailed, she accelerated to almost 90 miles an hour. They tried to pull alongside her green Oldsmobile four times, but each time they were forced to drop back — first by a jeep load of National Guardsmen, next by a highway patrol unit, then by a crowd of black marchers trying to cross the highway, and finally by a truck in the oncoming lane.

“That lady just hauled ass,” Rowe testified. “I mean she put the gas to it. As we went across a bridge and some curves, I remember seeing a Jet Drive-In Restaurant on my right hand side. I seen the brakes just flash one time and I thought she was going to stop there. She didn’t . . . she was just erratic. . . . Then we got pretty much even with the car and the lady just turned her head solid all the way around and looked at us. I will never forget it in my lifetime, and her mouth flew open like she — in my heart I’ve always said she was saying, “Oh God,” or something like that. . . . You could tell she was startled. At that point Wilkins fired a shot.”

Viola Liuzzo, a housewife and mother of five from Detroit, Michigan, was killed instantly. Leroy Moton, covered with her blood, escaped by pretending to be dead when the murderers came back.

I was eighteen years old, living in a white working class neighborhood in Queens, New York, with my parents when the news of the Liuzzo murder broke. I remember clearly the reactions in my house. “What was she doing down there, a woman like that, old enough to know better?” “Why would a woman with five children go to Selma? Was she crazy?” “Where was her husband? Couldn’t he stop her?”

The evening news reported that Mrs. Liuzzo had been murdered near Montgomery a few hours after the Voting Rights March ended. Liuzzo was 39 years old. She was one of 25,000 demonstrators who had answered Dr. King’s call to march to the state capital in support of a federal voting rights bill, and to deliver a petition to Governor George Wallace demanding protection for blacks as they tried to register to vote.

Because the Impala filled with Klansmen (including Tommy Rowe, who was on the FBI informer payroll) spotted Liuzzo leaving Selma with a black man sitting in the front seat of her car, she lost her life. And because the Birmingham FBI tried to cover up their carelessness in permitting Rowe — a known violent racist — to work undercover and unsupervised during the march, she also lost her reputation.

FBI chief J. Edgar Hoover himself crafted a malicious public relations campaign to blacken Liuzzo’s name in an effort to deflect attention from his Bureau. He successfully shifted the country’s concern from a brutal murder to a question of Liuzzo’s morals.

Hoover was desperate, and for good reason. He had to bury the fact that Rowe had telephoned the FBI on the day of the Liuzzo murder to report that he was going to Montgomery with other Klansmen, and that violence was planned. While Rowe claimed not to have known exactly what the plans were, he said Grand Dragon Robert Creel told him personally, “Tommy, this here is probably going to be one of the greatest days of Klan history.” That remark later led to speculation (never substantiated) that the Klansmen were scouting for an opportunity to kill a much more prominent figure — possibly Martin Luther King, Jr.

Hoover eagerly accepted Klan assistance in generating ugly rumors about Viola Liuzzo, and seduced the American press with a series of carefully engineered “leaks.” His caricature of Liuzzo as a spoiled, neurotic woman who had abandoned her family to run off on a freedom march took hold. Years of unrelenting accusations of her alleged emotional instability, drug abuse, adultery, and child abandonment nearly destroyed her husband and five children.

Until the Liuzzo family obtained access to the FBI files through the Freedom of Information Act — nearly fifteen years after her murder — they did not know that the slander had originated in the office of the FBI’s director.

In 1982, during a campaign for renewal of the Voting Rights Act, Washington Post columnist Jack Anderson observed that “evidently aware of the embarrassment the FBI would suffer from the presence of its undercover informer in the murderer’s car, J. Edgar Hoover marshaled the Bureau’s resources to blacken the dead woman’s reputation. This came at a time when the Bureau was also trying to smear King and find links between the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and the Communist Party.”

Despised as an “outside agitator,” Viola Gregg Liuzzo was in fact raised in rural Georgia and Tennessee. She grew up during the Depression in a Jim Crow culture of segregated schools, movie theaters, department store dressing rooms, water fountains, and churches. Her family moved to Ypsilanti, Michigan, in 1941 in search of war work at Ford’s Willow Run bomber plant. In 1942, 18-year-old “Vi” Gregg moved on to Detroit by herself, where she met Sarah Evans, who would be her closest friend for twenty years.

Sarah Evans, a black woman from Mississippi, encouraged Vi to join the NAACP, begged her not to go to Selma, and ultimately raised Vi’s youngest daughter Sally, who was only six when her mother was murdered.

Until 1963, Vi Liuzzo lived a somewhat ordinary life. She kept house for her husband, Jim, a business agent for the Teamsters, and helped her five children with their homework, planned birthday parties, took the girls antiquing and the boys camping, and went back to work as a hospital lab technician when Sally started school. Realizing that more education would allow her to advance, Vi — a high school dropout — took and passed the admission test to Wayne State University.

At Wayne State, a wider world opened to her. She read Plato, who defined courage as knowledge that involves a willingness to act, and Thoreau, who believed that a creative minority could start a moral revolution.

Even though she was Roman Catholic, Vi began attending services at the First Unitarian Universalist Church just two blocks from the Wayne Campus. It was a congregation committed to social justice; many were former Freedom Riders. She also attended weekly open houses hosted by chaplain Malcolm Boyd, who defined himself as a “Christian existentialist:” “We are what we do,” Rev. Boyd told his students, “not what we think or say.”

In this morally charged atmosphere, Vi Liuzzo made her decision to respond to Dr. King’s national call for help. She volunteered for the transportation service with the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. On her first day in Selma, she met fellow volunteer Leroy Moton, 19. She would later be accused of having an affair with this young man, who was the same age as Sarah Evan’s grandson, Tyrone.

Mrs. Willie Lee Jackson, a member of the SCLC’s food service committee, offered Vi a bed in her home along with six other women who had come to march. Vi stayed with the Jacksons all week, making arrangements for Mrs. Jackson’s daughter, Frances, and her five-week-old baby to come to Detroit and stay with the Liuzzos so she could finish high school. “She was very helpful with my children,” Mrs. Jackson remembered. “Seems to me she really loved children.”

Six hours after Viola Liuzzo’s murder, Klansman Tommy Rower called the Birmingham FBI to report that he knew who her killers were. Early the next morning, Rowe, 31, and three other white men were arrested — Collie Leroy Wilkins, Jr., 21; William Orville Eaton, 41; and Eugene Thomas, 43. Rowe was granted immunity for his testimony for the prosecution.

The trial of Wilkins, identified as the trigger man, opened on May 3, 1965, in Hayneville, Alabama. His defense attorney, Matthew Hobson Murphy, Jr., was Grand Klonsel of the United Klans of America. Robert Shelton, the Imperial Wizard, sat at the defense table throughout the trial. “I’m proud to be a white man,” Murphy told the jury, “and I’m proud that I stand up on my feet for white supremacy, not the mixing and mongrelization of the races.”

For three days, Klonsel Murphy hammered away at two themes: that Tommy Rowe had broken his Klan oath of loyalty in testifying against his fellow Klansmen and therefore could not be trusted, and that Mrs. Liuzzo was a white woman alone in a car with a black man at night, and whatever happened to her was her own fault.

The prosecuting attorneys — Arthur Gamble, Joe Breck Gantt, and Carlton Prudue — seemed either unwilling or unable to create sympathy for Viola Liuzzo as the victim of a brutal murder. “I’m a segregationist, too,” Gantt assured the jury, “but we’re talking about murder here.”

“I don’t agree with the purpose of this woman either,” Gamble offered, “but gentlemen, she was here and she had a right to be here without being killed.”

The trial ended in a hung jury. It wasn’t the outcome the Klonsel and the Imperial Wizard hoped for, and they had to cancel their “acquittal party.” But when journalist William Bradford Huie asked Murphy what he thought his chances were of getting an acquittal at a re-trial, the Klonsel replied: “Acquittal is certain. All I need to use is the fact that Mrs. Liuzzo was in the car with a nigger man and she wore no underpants.”

A second Alabama jury cleared Wilkins of all charges. None of the Klansmen were ever convicted of murder, but were sent to prison instead on federal charges of conspiracy to violate Mrs. Liuzzo’s civil rights.

Wilkins and Thomas were sentenced to ten years in federal prison and served seven. Eaton died of a heart attack before he could begin his term, and Tommy Rowe was slipped into the Federal Witness Protection Program.

In 1977, after using the provisions of the Freedom of Information Act to uncover the FBI’s role in destroying their mother’s reputation, the Liuzzo family brought suit against the federal government for negligence. They charged that the FBI knew Tommy Rowe and his fellow Klansmen were planning violence on March 25, 1965, yet did nothing to prevent it.

The case came to trial in 1983, but Federal District Judge Charles Joiner rejected the suit. In a 14-page opinion, he held that “Rowe did not kill, nor did he do or say things causing others to kill. He was there to provide information, and his failure to take steps to stop the planned violence by uncovering himself and aborting his mission cannot place liability on the government.”

Tony Liuzzo, wearing a white cardigan sweater that had belonged to his father (who had died five years earlier), burst into tears. Helen Fogel, reporting for the Detroit Free Press, summarized the situation succinctly: “For nearly a decade,” she wrote, “Tony Liuzzo lived and worked for the day when the word of a federal judge would show the world what manner of men his mother’s killers were, and make her heroism clear: even to doubters.”

Andrew Goodman, Michael Schwerner, and James Cheney, the young men murdered during the Mississippi Freedom Summer of 1964, were already civil rights heroes by the time of Viola Liuzzo’s murder. They were all young men of promise. A white activist college student, a selfless white social worker, a black community worker determined to fight for the freedom of his people — these were positive images.

Viola Liuzzo, however, was too old, too pushy, too independent, and she trampled on too many social norms to be a hero.

She’d ventured beyond the role of wife and mother to demonstrate on behalf of a social movement that a majority of white Americans felt was already moving “too fast.” Viola Liuzzo’s activism couldn’t be chalked up to youthful idealism. Hers threatened the family, the protected status of women, and the precarious balance of race relations.

Ironically, she’d been murdered precisely because she afforded such a clear symbol to the segregationists — a white female outside agitator driving after dark with a local black activist. This all resonated for them. In choosing her, the Klansmen sent a clear message that Northern whites and Southern blacks would understand.

In the cases of Goodman, Schwerner, and Chaney, the families worked hard to ensure that their sons would not be forgotten. All three families had been supportive of their sons’ involvement in the movement, while Jim Liuzzo had been more ambivalent.

After Vi’s murder, Jim found himself continually defending her reputation, refuting the vicious rumors, and trying to protect his children. He told a reporter for the Free Press, “My wife was a good woman. She’s never done anything to be ashamed of.” Two days after her funeral, a cross was burned on his lawn in Detroit.

Viola Liuzzo’s children were taunted by their classmates, shunned by their neighbors, and shamed by the cloud of suspicion that hung over their mother’s activism. She became the single most controversial of the civil rights martyrs.

I never forgot about her, about how angry people were at her. And I never forgot how they seemed to lose track of just who the victim was.

And gradually, I understood that Viola Liuzzo’s story is of an ordinary woman whose simple desire to be useful collided with America’s belief that change was happening too fast — and lost her life and her reputation for her trouble.

In this sense, we can see clearly in her life what author Melissa Fay Green once observed: “After the fact, historians may look back upon a season when a thousand lives, a hundred thousand lives, moved in unison; but in the beginning there are really only individuals, acting in isolation and uncertainty, out of necessity or idealism, unaware that they are living through an epoch.”

Tags

Mary Stanton

Mary Stanton is the author of From Selma to Sorrow: The Life and Death of Viola Liuzzo (University of Georgia, 1998). (1999)