Mining the Mountains

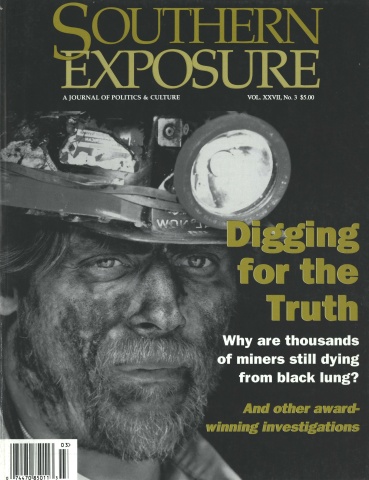

This article first appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 27 No. 3, "Digging for the Truth." Find more from that issue here.

In his series “Mining the Mountains,” Ken Ward, Jr., of the Charleston Gazette (W. Va.), assembled an enormous amount of previously unavailable information about the growth of strip mining in West Virginia and the failures of government to properly regulate mine operators.

Drawing on Ward’s research, the West Virginia Highlands Conservancy and a group of private citizens, successfully sued federal and state agencies, forcing them to admit that have not properly enforced strip-mining laws. The following article, the first in the series, introduces several of the important issues and players in this ongoing struggle.

SHARPLES, W.Va. — On a cold rainy night last December [1997], more than 125 people gathered to talk about a strip mine. They came from Blair, Clothier, and Sharpies to pack the bleachers of an elementary school gym.

Just over the ridge from the school, Arch Coal, Inc. had stripped 2,500 acres of the Logan County hills around Blair Mountain. The company has applied for a permit to mine 3,200 more. If state regulators approve the new permit, giant shovels and bulldozers will eventually lop off the mountaintops of an area as big as 4,500 football fields.

Residents of the tiny communities along W.Va. Highway 17 complained Arch Coal’s existing mine already makes their lives miserable. Why, they asked regulators at the hearing, should the company get a permit to mine more?

Melvin Cook of Blair was the first to walk across the gym floor to a microphone and speak up. He complained about the blasting. Arch Coal dynamites rock formations to loosen them, to make it easier to get at the coal underneath. Residents say the blasts toss rocks and dust into neighboring communities. Residents also say blasts shake their homes, crack foundations, and damage water wells.

“You can’t bear it,” Cook said. “It has torn my house all to pieces.”

James Weekly told regulators he’s worried the new mine will spread problems toward his home up Pigeon Roost Hollow north of Blair. “We need some laws changed on this stripping,” Weekly said.

Dozens of United Mine Workers also filled the gym bleachers. The miners said they wanted jobs at the new mine. But they agreed the company should make sure mining doesn’t disturb area residents.

“I think you need to spend a whole lot more time and appoint a committee or something or somebody to check this out,” said Charles Kimbler, a UMW local president.

More and more coalfield residents are turning out for hearings like the one in Sharples. Regulators and the media are paying more attention, too. Strip mining is a big issue again.

Larger than Logan

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, people complained about strip mining all the time. Activists packed courthouses to lobby against it. Housewives sat down on dirt roads to block coal trucks and bulldozers.

By 1977, Congress was forced to pass the Surface Mine Control and Reclamation Act to protect coalfield residents and the environment. Since then, strip mining has boomed. Thirty years ago, only about 10 percent of West Virginia coal production came from strip operations.

Today, strip mining accounts for roughly a third of all coal produced in the state.

Earth-moving machines used by coal companies have gotten bigger and bigger. They tower over old-time shovels and bulldozers that stripped coal off hillsides. Today, a few skilled miners working these machines can literally move mountains.

Since 1981, nearly 500 square miles of the state — an area larger than Logan County — has been strip mined, according to the U.S. Office of Surface Mining. In the last five years alone, the average size of new mining permits issued each year has doubled, to more than 450 acres, according to the state Division of Environmental Protection. Last year, DEP issued new permits totaling 31 square miles, an area larger than the city of Charleston.

For the most part, this mining boom went on without public outcry. A few environmental activists and industry lobbyists wrangled about mining rules in Capitol corridors. Government regulators and company lawyers negotiated permits in obscure court hearings. But most people thought the 1977 federal law would rein in the strip miners.

In the last two years, that changed.

Dozens of activists turned out for a “Citizen Strip Mine Tour” to see first-hand the effects of mining on coalfield communities. Hundreds attended a forum in Huntington to learn about environmental dangers of “mountaintop removal” mining.

Residents of Mingo, Logan, and Boone counties came to Charleston several times this year to lobby the Legislature for tougher mining laws. A group of them drove to Washington, D.C., in January to complain to their congressman.

Coal operators say all this attention is unwarranted. Some have hauled out standard jobs-vs.-the-environment arguments. Others insist the fight over stopping strip mining ended decades ago — and that they won.

Officials of a few strip-mining companies welcomed a closer look. Arch Coal, for example, says scrutiny will show they mine without permanently scarring the land.

“I want everybody to understand that we have been trying to work with the community,” said John McDaniel, a top Arch Coal engineer. “It’s not as one-sided as everybody tries to make it appear.”

Government officials offer mixed views. Some regulators turned to publicly touting their own hard work. Others are offended by the suggestion they do not adequately protect the environment. A few have privately regrouped to see if more needs to be done.

“We think we’re doing a daggone good job, but we could always do better,” said John Ailes, chief of the DEP Office of Mining and Reclamation.

There’s little doubt the federal strip-mining law has made improvements. All mines must get permits from the state or federal government. Operators are required to protect water quality and reclaim mined land. Regulators conduct frequent inspections. Renegade operators are banned from the business.

But coalfield residents, environmental lawyers, and regulatory experts have raised serious questions about whether this program works. They ask:

■ Is the mining law properly enforced by state regulators? Is more federal oversight needed? Or is the law obsolete and unable to control today’s huge mountaintop removal jobs?

■ Are operators making coalfield communities unlivable? Does blasting diminish the quality of life? And what about the threat that large valley fills will collapse onto or flood homes?

■ Can much of the state’s valuable low-sulfur coal only be economically mined by huge machines? Or could operators get at this coal without doing as much damage? Could they use underground mining instead and provide more jobs?

■ Can company engineers literally turn mountains upside down and return the land to a usable form? Would sharp peaks be better if they were flattened for shopping malls, factories, and schools? Or is strip mining forever ruining West Virginia’s hills and streams?

“It’s no longer something that is just happening in a little hollow where two or three people are being hurt,” said Cindy Rank, mining chair of the West Virginia Highlands Conservancy. “It’s a bigger issue now.”

Spoil and Overburden

By late 1995, Arch Coal subsidiary Hobet Mining, Inc., had strip-mined nearly 10,000 acres of Boone County hills and hollows. The company was ready to move west across the Mud River into Lincoln County. In January 1996, Hobet proposed a new operation. The Westridge Mine would strip 2,000 acres and produce more than 3.2 million tons of coal every year for about a decade.

Hobet needed somewhere to put the mountains removed to reach the coal. Coal operators call these mountains overburden. Much of this rock and earth — operators call it spoil once they dig it up — is normally dumped into nearby hollows in piles called valley fills.

In this case, Hobet wanted to fill 2¼ miles of Connelly Branch with enough spoil to fill 1.1 million railroad cars, a train that would stretch from Charleston to Myrtle Beach, S.C., and back a dozen times.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency objected.

“Connelly Branch is the longest stream in West Virginia that has ever been proposed to be covered by a valley fill to our knowledge,” EPA Region III water division Director Al Morris wrote to the state in September 1996. “The loss of Connelly Branch could possibly affect aquatic life in the Mud River, particularly in combination with other existing and proposed valley fills in the watershed.”

Morris said IPA would not allow the permit to be issued unless Hobet Mining considered alternative ways to dispose of the mine spoil. He also said the state must agree to study long-term valley-fill environmental impacts.

In February 1997, EPA backed off. Hobet agreed to make a few minor changes in the valley fill. The company, for example, would do periodic testing to see if the fill harmed the Mud River downstream. No one performed any in-depth studies of valley-fill environmental effects.

Four months later, in June, EPA objected to another valley-fill permit. A.T. Massey wanted to fill in a two-mile segment of James Creek along the Boone-Raleigh county border. This time, EPA officials suggested Massey should consider “not mining parts of coal seams where stream filling is necessary for excess overburden disposal.”

In August, EPA backed off again. The agency “concluded that there do not appear to be options for further reducing the fill length, other than significantly changing the amount and type of mining.

“[But] we are still very concerned about the disturbing trend toward larger fills and increased stream impacts by coal companies, and wish to work closely with DEP to prevent these impacts where possible,” EPA added.

More than seven months later, EPA officials still say they are worried about the growing size of valley fills and cumulative effects of strip mining on water quality. (Asked for his general impression of strip mining, Gov. Cecil Underwood said it would be good for long-term economic development efforts. “My view of mountaintop removal is it creates a lot of artificially flat land in places we don’t have flat land.”)

“More than a Headache”

For years, DEP and coal industry lobby groups co-sponsored an annual mine tour. It focused on successful reclamation projects and advances in mining technology.

Wendy Radcliff, DEP’s environmental advocate, wanted to show the other side. So in mid-August, reporters, citizens, and DEP officials piled into four-wheel-drive vehicles and visited coalfield trouble spots.

In Logan County, the group parked in the gravel lot at the Blair Post Office. Carlos Gore told them about an Arch Coal blast that tossed rocks bigger than softballs into his backyard.

“If a rock this big hits you or your car or your house, you’re going to have more than a headache,” Gore said. “It’s going to ruin your whole week, because there’s going to be a funeral.”

Vicky Moore said blasting dust is often so thick she can’t see her neighbors’ homes. She has to turn on headlights to drive.

“The surface mining law is designed to protect people,” said Pat McGinley, a WVU law professor who represents Moore in a suit against Arch Coal.

“It’s designed to protect communities and it’s designed to protect the environment,” he said. “But it’s not being enforced.”

Coal industry lobbyists Bill Raney and Ben Greene stood at the edge of the post office parking lot and listened to the residents’ stories.

“Of course you have sympathy for them,” said Raney, who is president of the West Virginia Coal Association.

“But the one thing that strikes me is that there was no malice intended,” Raney said. “No one in the industry sets out in the morning to do something like that.”

A few weeks later, Greene’s group, the West Virginia Mining and Reclamation Association, attacked the DEP tour.

“The citizens’ tour appears to be the culmination of a well-coordinated, summer long, anti-coal campaign,” the newsletter said. “All signs point to a regional campaign, with West Virginia as the focal point. Just because you’re paranoid doesn’t mean they’re not out to get you.”

“Blasting Scares Me”

Kayla Bragg and Dustin Moore could barely reach the microphone in the House of Delegates chamber. They drove to Charleston with their parents for a public hearing in late February. The Braggs, the Moores and other coalfield residents wanted the Legislature to crack down on strip-mine blasting.

Currently, it’s almost impossible to prove that mine blasting damaged nearby homes. A bill sponsored by Delegate Arley Johnson (D-Cabell) would have fixed that. Under the bill, any structural damage that did not exist prior to mining would be presumed to have been caused by blasting. The bill would apply to homes within 5,000 feet of blasting sites.

“Blasting scares me and I can’t breathe good when it stirs up the dust,” said Dustin, an 8-year-old asthmatic whose mother is Vicky Moore. “One day a blast went off and knocked my school picture down.”

Kayla, a 10-year-old from Beech Creek in Mingo County, said, “When a blast goes off, I get scared because the windows shake. I would very much appreciate it if you would pass this blasting bill.”

The blasting bill did not pass. The Legislature agreed to study the issue for a year in monthly interim committee meetings.

“The coal industry killed our blasting bill, and then they fought hard to kill this study resolution,” said Jack Caudill, a West Virginia Organizing Project activist. “It’s about time the Legislature did at least one small thing for the common people.”

Coal industry lobbyists had a bill they wanted the Legislature to pass, too. The measure would make it much easier for companies to fill in streams with excess rock and earth from big strip mines.

Federal regulators opposed the bill. Citizens and environmental activists fought it. Top state DEP officials, including Deputy Director Mark Scott and water office chief Barb Taylor, testified against it.

Two days before the session ended, DEP Director John Caffrey intervened. Caffrey said publicly that his agency wasn’t opposed to the bill. Scott and Taylor weren’t speaking for the agency when they testified against it, Caffrey said.

House Speaker Bob Kiss, D-Raleigh, pushed the legislation. K.O. Damron, lobbyist for A.T. Massey, was its biggest advocate among industry officials. On the last night of the session, the bill was approved.

Rank, the Highlands Conservancy member, wasn’t surprised. But she said the fight over strip mining is nowhere near over.

“I think the industry is losing the fight,” she said last week. “They’re losing in the public eye. They’re losing on legal grounds. They’re losing on technical grounds and scientific grounds. So they chose to take the battle to where they have the most power the political process at the Legislature and among the people who run the DEP.

“But the rest of the world is beginning to understand there are problems,” she said. “Everyone has to become more aware of what’s going on. If people don’t see it, [coal companies] will just keep doing what they’re doing.’’

Tags

Ken Ward, Jr.

Charleston Gazette/Sunday Gazette-Mail (1999)