The Greek Divide

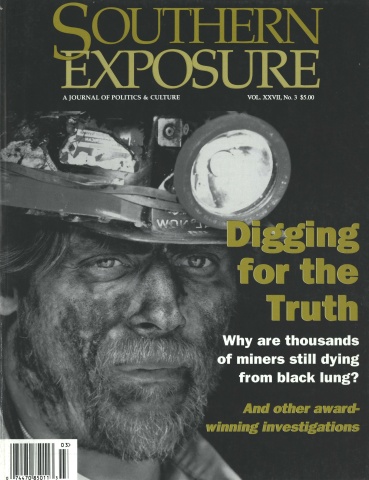

This article first appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 27 No. 3, "Digging for the Truth." Find more from that issue here.

“We love everybody — we’re Christians. But that doesn’t mean that we want everybody to be our sister.”

— Sorority member at the University of Alabama

Right on time, into the August heat thick as honey, the Tri-Delts bounce out of their three-story wedding cake of a house, two lines of young women looking Jackie Kennedy-esque in sugary pinks, greens and blues, smiling with unimpeachable welcome. They greet the group of thirty church-dressed girls wilting on the sidewalk, calling them by name: “Courtney! Anna-Kate! Sarah!” They ask in voices like cream, “Are you enjoying rush? Are you having fun? Are you psyched for the football game?”

The girls disappearing gratefully, if nervously, inside the big air-conditioned house will go to seven parties today and seven tomorrow. Then the process of elimination begins: some sororities will invite them back, some not. The girls will accept some invitations and decline others until, in the end, they attend two highly emotional “Serious Night” or “Pref” parties. The next day they must commit, hoping that the sorority they want will also want them.

By day, gangs of girls in pearls with expensive shoes and discreet manicures roam the well-watered lawns of the University of Alabama campus, trying to choose between Chi Omega and Kappa, Tri-Delt and Pi Phi. By night, cohorts of boys in Ralph Lauren pastels wander Old Row, a section of University Boulevard that looks like a plantation house museum, heading for fraternity parties and working out if they want to be a Kappa Alpha or an SAE, a Deke or a Fiji.

These are not inconsequential decisions. Which house you join determines to a large degree your social world: whom you date, whom you befriend, even whom you marry.

It can also determine your political and economic worlds. Fraternities (and now sororities) at Southern universities are players in Southern politics: Andrew Young, former mayor of Atlanta and an Alpha Phi Alpha, got counted-on support from influential fraternity brothers. One-time presidential candidate Elizabeth Dole, a Delta Delta Delta at Duke, enlisted campaign help from sisters across the country. Don Siegelman, Alabama’s new governor and a Delta Kappa Epsilon at Alabama, is but the latest alleged recipient of the power and pull of the “Machine,” an elite super-fraternity that goes back to the days of Senator Lister Hill.

So university rush isn’t child’s play, however silly the lip-gloss and the platitudinous party conversations, the silver punch bowls and the tears might seem. And beneath ritual anxiety of rush, a more serious social drama is unfolding.

Although the University of Alabama has a substantial minority enrollment — 14 percent African-American — fall rush is almost all white. There are four historically black sororities at Alabama (Alpha Kappa Alpha, Sigma Gamma Rho, Delta Sigma Theta and Zeta Phi Beta) and four historically black frats (Alpha Phi Alpha, Kappa Alpha Psi, Phi Beta Sigma, and Omega Psi Phi), but they seek new members during spring semester in a more sober fashion, akin to job interviews rather than fashion shows or cocktail parties. That rush is almost all black.

At this moment, there is not a single integrated fraternity or sorority at the University of Alabama.

But all this may change if the University of Alabama administration has its way. Last year, President Andrew Sorensen put together a Task Force for Greek Diversity, charged with finding ways to bring the racially-divided rush seasons together and encourage crossing the color line in membership. This would revolutionize a century-old system one University of Alabama professor calls “apartheid.”

Two Worlds

While both rushes are theoretically open to everyone, regardless of race or religion, in reality almost no one crosses the color bar. In 1998, two young black women did rush, but neither received a bid to join a white sorority. Hank Lazer, assistant vice president for undergraduate programs and a member of Alabama’s Greek Diversity Task Force, says, “Sure, Greeks claim there’s equal opportunity for membership, but when the races are so separate, how inviting is it to try?”

Citing racism, classism, sexism, binge drinking, date rape, and a less than serious attitude toward study, some colleges in New England such a Williams and Bowdoin have done away with sororities and fraternities. Dartmouth, known as the Ivy League’s party school and home of the original “Animal House,” plans to force its Greek houses to become “substantially co-educational.” James Wright, President of Dartmouth, told The New York Times that he wants to “re-imagine” campus life, crossing “lines of race and of background as well as lines of gender.” Dartmouth students are protesting vociferously.

No college presidents in the South suggest that fraternities and sororities go co-ed, but the problem of racial division exercises administrative brains at many Southern institutions. The University of Mississippi has deferred rush for the white fraternities and sororities until late September, giving students a chance to bond with their college and their classmates before disappearing into mostly all-white houses. According to Ron Bender, Director of Greek Affairs at UNC, rush in Chapel Hill has not only been deferred until after classes begin, but the university discourages expensive rush wardrobes and downplays alumni recommendations, trying to attack the class divisions — almost as important as racial divisions — that have always plagued the Greek system.

Alabama’s task force is modest in its recommendations, encouraging a gradual shift in emphasis from fall rush to spring, sponsoring a convocation with the governing bodies of both white and black fraternities and sororities participating, and trying to foster “non-traditional” participation in rush.

The current set-up is Byzantine: white sororities are run by Panhellenic, white fraternities by the Interfraternity Council, and black sororities and fraternities by Pan-Greek. In addition, while white fraternities and sororities rush freshmen and a few sophomores, black fraternities and sororities do not consider anyone for membership until he or she has been on campus at least one semester and established an academic and service track record.

Two Histories

And as if this clash of rush schedules isn’t enough of a roadblock on the path to unity, white and black Greek groups grew out of vastly different social circumstances and ultimately have different goals. Herman Mason, an expert on black fraternities, national archivist for Alpha Phi Alpha (the oldest black Greek organization) and author of two books on the fraternity, says that while some of the fraternal ideals were taken from white models, “the symbols and names are very much connected to African-American history.”

Alpha Phi Alpha was founded in 1906 at Cornell (the oldest black sorority, Alpha Kappa Alpha, was founded in 1908 at Howard) at a time, Mason notes, of terrible racism and violence towards African Americans. “Lynchings were abundant. Jim Crow was the law. Black fraternities supported each other and lifted people up.”

In contrast, white fraternities were mostly an offshoot of Freemasonry, founded both to inspire high ideals in the young members of the ruling class and cement their hegemony. White fraternities have not been embattled minorities since the Masonic scare of the 1840s, which forced America’s first fraternity, Phi Beta Kappa — now an academic honorary — to go public with its secret rituals.

White sororities, mostly founded between 1851 and 1910, were initially a feminist response to fraternities, appearing at mostly women’s colleges. The late Miriam Locke, Professor Emerita at the University of Alabama and a founder-member of the Kappa Kappa Gamma chapter there, once remarked that girls used to join sororities to meet other girls passionate about learning.

“The men tended to get all the educational opportunities. In a sorority, girls could band together and study,” Locke said. “Nowadays I’m scared that all they’re interested in is drinking and such.”

It’s fair to say that all Greeks, male and female, black and white, are into drinking and such. They all have theme parties, formal dances, swap dinners and socials. They all counter, with some justification, that they do a great deal of charity work for everything from Habitat for Humanity to diabetes research.

To the outsider, one frat boy or sorority girl might seem much like another. But that’s like saying one Christian is just like another Christian. A high-church Episcopalian isn’t the same as a foot-washing Baptist. There are differences in style and sensibility.

A former president of Kappa Alpha (KA brothers call themselves “the last Southern gentlemen”) was recently quoted in Salon magazine saying, “I can’t imagine why anyone would join a fraternity that did not celebrate his heritage.”

Joycelyn Carr, a member of Delta Sigma Theta at the University of Alabama, concurs, saying that “black sisterhood” is at the center of her sorority experience: “Not every woman — regardless of race — is Delta material.”

Campus Rebels

I was — am — in a sorority (they teach us that sisterhood is forever). I pledged Sigma Kappa twenty years ago, when being Greek was uncool, especially at Florida State, “the Berkeley of the South.”

We Greeks thought of ourselves not as rump segregationists but as an elite, upholding standards of ladyhood and scholarship, while partying hard. Of course, my house, like all the other Panhellenic sororities on campus, was all white: no one who wasn’t white even went through rush. We thought we were on the cutting edge of diversity when we pledged a Jewish girl. And we had five or six actual Catholics.

We would have rejected the idea that we were racist, that the system was racist. Most of us believed in integration, in equal rights, in social justice, even if we did laugh at mildly racist jokes, even if we were thrilled to get an invitation to Kappa Alpha’s party, “Old South,” to which our dates wore Confederate uniforms and we wore hoop skirts.

When I came to teach at the University of Alabama in 1990, it didn’t look like much had changed in the Greek world. The white fraternities and sororities had huge plantation-style houses. The KAs still flew the Confederate battle flag. The black fraternities had step-shows attended by mostly black students.

White racism reared its head in more striking incidents. A cross was burned on the lawn of Alpha Kappa Alpha when they moved into a house on campus; a black homecoming queen was booed by white fraternity boys; and a couple of white sorority girls went to a “Who Rides the Bus?” social in blackface with afro wigs and basketballs shoved under their dresses.

But to its credit, the University of Alabama has grown since the days that George Wallace famously stood in the door of Foster Auditorium in 1963, trying to bar the admission of Vivian Malone and James Hood. The school actively (if incompletely) has taken steps to deal with its egregious Jim Crow past, building a thriving African American Studies program, boosting undergraduate minority enrollment to 18 percent, and aggressively recruiting African-American professors. But in a state that is 25 percent African American, nobody thinks that enough has been done.

Hank Lazer recalls that Greek integration was raised in the faculty senate over fifteen years ago, and it’s taken this long to address the issue formally. He says he’s a bit disappointed in the tepid measures taken to bring black and white students together in one rush, but points out that “it is a mark of the maturity of the institution that we are able to discuss it at all.”

Pat Hermann, a white English professor, takes a much harder line. Hermann has repeatedly called on the university to shut down all “apartheid” fraternities and sororities (some of whose houses are on university land) until they integrate.

Perhaps the biggest roadblock is that the sister and brothers — both white and black — don’t agree. Delta Joycelyn Carr says, “diversity training is one thing, but forcing people to integrate is too extreme.”

A member of Pi Beta Phi, a white sorority, who did not want to give her name, said that if integration occurs, “it needs to come from the students. If we’re forced into it, we’ll rebel.”

Cedric Rembert, a chemical engineering major and president of the African-American Pan-Greek umbrella, says he has no problem with the university trying to promote mixing of blacks and whites under the Greek aegis: “It’s certainly worth doing. Maybe Alabama will be a model for other places.”

But Rembert, a member of the historically black Omega Psi Phi fraternity, resists compelling Greeks to change their rush customs and membership traditions. “Opportunity to join is one thing,” he says, “but no one should be forced to be in any one group.”

Radical Change

None of the students I talked to said they felt threatened by the university’s push toward Greek integration. They don’t believe is will happen soon — not during their time at Alabama, anyway.

Herman Mason, however, thinks African-American Greeks ought to feel threatened. “This whole thing endangers our traditions. Fraternities and sororities are private organizations, after all.”

Mason speaks of how black fraternities and sororities have been instrumental in the fostering of a black middle class and invaluable networking opportunities for African Americans that have to live and work in a majority-white world.

“I would shudder to think that there would be a mandate to integrate,” Mason says.

Besides, he points out, Alpha Phi Alpha has been integrated — a bit — since the 1940s, when the fraternity took its first white member at the University of Chicago. In fact, all the other historically black Greek national organizations are integrated, just in small numbers.

Outside of the South, white fraternities and sororities are taking more and more Latino, Asian and black members. Every once in a while, a Southern white Greek chapter will have one, maybe two, black members. But this is rare and, for the University of Alabama administration, not good enough.

“The real world, the business world, is not all black or all white,” says Dr. Charles Brown, co-chair of the university’s diversity committee. “You need to communicate with people different from you.”

While nobody is satisfied with the task force’s recommendations, he feels Alabama is ahead of other large Southern universities. Indeed, the University of Georgia, FSU, Ole Miss and North Carolina have no concerted Greek integration plans.

Darrell Ray, assistant coordinator of Greek Life at Georgia and former vice-president of Pan-Greek at the University of Alabama, says there’s a “lack of desire” for Greek integration, though he points out that several new white fraternity “colonies” (re-established houses) have some African-American members.

Ron Bender says the UNC administration has chosen not to formally mandate integration. “There are many ways of being Greek and no one way is the right way,” he says. There are the usual historically white and historically black sororities and fraternities at Chapel Hill, but also a Native American sorority, a multicultural sorority, and a Christian fraternity with a half-black, half-white membership. The white Sigma Nus and the black Alpha Phi Alphas hold a joint party every year, and a black frat has even taught a white one how to step dance.

At Alabama, the social lives of Alabama’s Greeks remain segregated. One of the sub rosa fears of alumni and some students (mostly white) is that integrating Greek houses will lead to interracial dating, still a taboo in much of the South. But almost no one will say this out loud, preferring to talk about how political life in the student government remains segregated.

So it will be interesting to see what will happen at Alabama, if white Greeks remain white — and in charge — or if diversity slowly and organically prevails. Or maybe the administration, wanting to distance itself from the University of Alabama everyone remembers — George Wallace shaking his fist at Civil Rights, Autherine Lucy being attacked on her way to the library — will impose radical change.

“I do not intend to mandate integration within the Greek system on the basis of race, ethnicity, religion or gender,” Alabama’s President Sorensen insists.

But, he warns, if nothing changes, further steps will be taken.

Tags

Diane Roberts

Diane Roberts is a writer, radio commentator, and the author of The Myth of Aunt Jemima. (1999)

Diane Roberts is author of several books and a professor of English at the University of Alabama. (1997)