Dust, Deception and Death

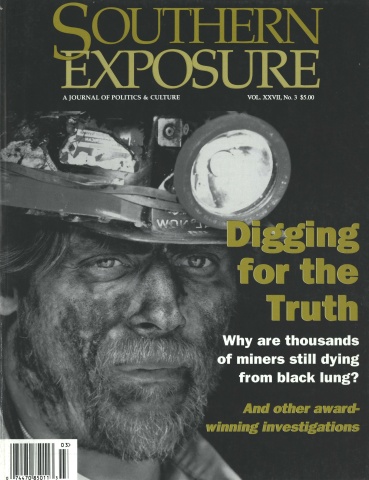

This article first appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 27 No. 3, "Digging for the Truth." Find more from that issue here.

In a five-part series featuring articles by Gardiner Harris and Ralph Dunlop, the Louisville Courier-Journal uncovered a quiet but deadly tragedy unfolding in the nation’s underground coal mines: 30 years after Congress placed strict limits on airborne dust and ordered mine operators to take periodic tests inside their mines, black-lung disease still contributes to the deaths of almost 1,500 miners every year, largely because of widespread cheating on air-quality tests. And under Kentucky’s new workers’ compensation law, almost no coal miners qualify for black-lung benefits. The Courier-Journal’s investigation involved interviews with 255 current and former miners and computer analysis of more than 7 million government records. As a result, the federal Mine Safety and Health Administration began spot inspections of mines with impossibly low dust ratings. Several state legislators are pushing for changes in the state workers’ compensation system. Kentucky and federal mine safety officials have agreed to cooperate more fully in the future. Plaintiffs’ attorneys and the United Mine Workers of America are exploring whether to file class-action lawsuits against the coal industry. And U.S. Sen. Paul Wellstone, D-Minn., has called for Senate hearings into the newspaper’s findings.

LOUISVILLE, Ky. — Hundreds of coal miners nationwide die each year of black-lung disease because many mine operators, aided by miners themselves, cheat on air-quality tests to conceal lethal dust levels. And while the federal government has known of the widespread cheating for more than 20 years, it has done little to stop it because of other priorities and a reluctance to confront coal operators, an investigation by The Courier-Journal shows.

“Yes, even a cursory look (at federal dust-test records) would lead one to believe that inaccurate samples continue to be submitted in large numbers,” said J. Davitt McAteer, the government’s top mine-safety official.

The result: Many underground miners toil in coal dust so thick that over the years their lungs become choked with scars and mucus, and they eventually suffocate.

In 1969, Congress placed strict limits on airborne dust and ordered operators to take periodic air tests inside coal mines. The law has reduced black lung among the nation’s 53,000 underground coal miners by more than two-thirds. But because of cheating, the law has fallen far short of its goal of virtually eliminating the disease.

The number of sick miners is unknown, but government studies indicate that between 1,600 and 3,600 working miners — and many retirees — have one of the lung disorders collectively called black lung.

In a year-long investigation, The Courier-Journal interviewed 255 working and retired miners in the Appalachian coal fields and analyzed by computer more than 7 million government records. Unearthed was a mountain of evidence that cheating is widespread.

The Findings:

■ Widespread fraud: Nearly every miner said that cheating on dust tests is common, and that many miners help operators falsify the tests to protect their jobs.

“I’ve never known of one to be taken right, and I was a coal miner for 23 years,” said Ronald Cole, 52, of Virgie, Ky., who left the mines in 1994. Like many of the miners interviewed, Cole has black lung. Two dozen former mine owners or managers acknowledged that they had falsified tests.

■ Tainted tests: Most coal mines send the government air samples with so little dust that experts say they must be fraudulent.

■ Lax enforcement: The Mine Safety and Health Administration ignored these obviously fraudulent samples for more than 20 years, until The Courier-Journal began asking about them late last year. The agency also paid little attention during the 1970s and 1980s to government auditors and outside experts who repeatedly warned about dust-test fraud.

■ Botched inspections: Agency inspectors oversee tests at least once a year, but these tests also have been inaccurate. Many inspectors fail to closely supervise the miners taking these tests, and since 1992, 11 inspectors have been convicted of taking bribes. In recent years, the government has improved its test monitoring because the agency is now headed by McAteer, a longtime mine-safety advocate. Yet even today tests that are overseen by inspectors rarely measure the dust levels that miners actually breathe.

■ The union factor: Dust tests tend to be taken more accurately at union mines than at non-union mines.

■ Dirty surface mines: Dusty conditions and cheating on tests are also common at surface coal mines, and strip-mine drillers are especially at high risk.

■ Betrayed miners: Many miners who develop black lung feel betrayed by the state and federal governments when, after years of helping mine operators cheat, they are denied disability payments.

In Kentucky, legislators — at the urging of Gov. Paul Patton, a former coal operator — passed a workers’ compensation law in 1996 that made it tougher for black-lung victims to qualify for benefits. The law has cut insurance premiums of some coal companies almost in half.

“The dust-testing system has been rife with fraud from day one,” said Tony Oppegard, directing attorney of the Lexington-based Mine Safety Project, which represents miners with safety complaints. “It’s a national tragedy and a national disgrace.”

But coal industry representatives say cheating and dangerous dust levels are isolated problems. They blame most miners’ lung disease on smoking. While smoking is common among miners, medical research shows that coal-mine dust damages lungs in similar ways.

“We have been the victims of allegations of fraud and cheating and not caring about miners since day one,” said Bruce Watzman, vice president of health and safety for the National Mining Association. “That’s not true in this industry.”

Mine-safety advocates and small numbers of miners have said for years that cheating on dust tests was the reason black lung had not been wiped out. But the coal industry has always fiercely denied that, the government has largely ignored them, and most miners have been afraid to accuse their employers of cheating.

The mine-safety agency did accuse hundreds of mine operators in 1991 of tampering with dust tests during the previous two years, but it failed to prove its case in court, and most of the civil charges were dismissed.

Miners: Tests Were Always Rigged

The Courier-Journal has now amassed evidence that dust-test cheating in widespread and has existed much longer than the mine-safety agency ever alleged or openly acknowledged.

That new evidence includes 234 current and former miners who said in interviews that they, or others they witnessed, routinely falsified tests.

Common practices they described include running sampling pumps less than the required time or placing them in clean air away from working areas. Scores of miners said they had never seen a dust test done correctly. Just 21 of those interviewed said they had no knowledge of cheating. While some miners said they are bullied into falsifying tests, many others said they participate because they think mines will close.

“You either do it or the mines shut down,” said Elmer Causey, 43, of Viper, Ky. He left mining in 1992 with black lung. “And if the mine shuts down, you ain’t got no job. And if you ain’t got no job, you got no food on the table.”

Few other jobs in the coalfields pay nearly as well — the state says the average Kentucky coal miner made about $40,000 last year working 49 hours a week.

The evidence includes the finding that, in 1997, at about half the nation’s underground coal mines, at least 15 percent of the air samples taken in working areas were almost dust-free.

“When you go to Louisville and have your lungs checked and you come up with second-stage black lung, and them (dust-testing) machines are showing it’s dust-free, something’s wrong,” said Jerry Cornett, 40, a miner from Baxter, Ky.

And the evidence includes 25 former mine owners or managers who told The Courier-Journal that they cheated on the tests because they would have been at a competitive disadvantage if they had not.

“The health of the men never entered into it,” said Gordon “Windy” Couch, 58, of Clay County, Ky. Couch was the safety director of giant Shamrock Coal from 1977 to 1992. “Controlling the dust just wasn’t part of the calculation. Production was number one.”

A lawyer for Shamrock said he wouldn’t respond to Couch’s accusations. The company has been sued by 19 of its former employees, who allege that cheating on dust tests caused them to get black lung.

While the government said in the 1991 crackdown that no miner had been hurt by the cheating, The Courier-Journal found that thousands of miners have been disabled or died. Between 1972 and 1994, the deaths of 54,248 U.S. miners — 3,007 in Kentucky — were blamed at least partly on black lung. The precise number harmed by cheating is unknown because many were exposed to high dust levels before 1972, when the strict dust limits ordered by the Federal Coal Mine Health and Safety Act of 1969 went into effect. Recent research also suggests that some miners would get black lung even if dust levels were consistently low.

But black-lung researchers said the lower incidence of the disease among British miners — who worked in government-owned mines where dust-test cheating was rare — is strong evidence that hundreds of American miners fall ill every year because of widespread fraud.

Safety vs. Disease

Black lung’s grisly toll has been ignored largely because mine explosions and cave-ins have gotten most of the attention from the federal mine-safety agency and the public. But regulators’ focus on accident fatalities ignores a simple fact: Black lung displaced accidental deaths as the principal killer of miners at least 50 years ago.

Only 30 coal miners died in accidents nationwide last year — five in Kentucky — making 1997 the safest year ever. In 1994, by comparison, the death certificates of 1.478 former miners nationally — 81 in Kentucky — listed black lung as one of the causes of death, according to the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, or NIOSH. (More recent national numbers aren’t available, but 1995 and 1996 figures from the four states that account for most black-lung deaths didn’t change significantly.)

Two NIOSH studies of black lung’s prevalence provide another picture of its impact. The last reliable study, done from 1985 to 1988, showed that 7 percent of miners had the disease. MSHA officials now say about 3 percent of miners have black lung, but that figure is based on an unscientific survey of miners who volunteered for chest X-rays from 1992 to 1995.

While that survey was flawed, it did find numerous black-lung victims who had started work after the new dust limits went into effect in 1972.

For example, Ben Vanover didn’t start mining until 1973. By 1985, after working for seven different coal companies, his breathing was so bad that he would often drop to his knees and lean against the mine wall to catch his breath. He quit. The Mine Act proclaims that miners should be able to work their entire adult lives — 45 years — without fear of getting black lung. Vanover, 57, of Stanville, Ky., made it just 12 years.

The Floyd County resident, who says he quit smoking in his 20s, now sleeps with an oxygen mask but still wakes up two or three times a night, gasping for air. In a recurring nightmare, he’s being pulled underwater.

“You don’t think too much about it when you go into the mines, but once your breathing gets bad you realize you made a mistake. By then you already got it, and it’s too late.”

Vanover will join his father, father-in-law and generations of Appalachians who have died of black lung. This tradition has bred a fatalism in the coalfields that helps explain why miners help operators cheat and don’t complain openly about dust.

“Almost every family in Central Appalachia has a family member who died of black-lung disease,” said Ron Eller, director of the University of Kentucky’s Appalachian Center. “It’s as ordinary as diabetes or high blood pressure or cancer in the region.”

Lives vs. Profits

Researchers, safety advocates, and union officials insist that coal can be mined safely and profitably — something the industry says it is doing — but most miners and mine managers interviewed said underground mines would close if operators had to pay the costs needed to keep coal dust within federal limits. The managers say they are squeezed by cheap coal from huge strip mines in Wyoming.

“You can’t run a mine, make money and pass a dust test. The profit margins are too slim,” said Paul Gilliam, 46, of Mayking, Ky., who retired in 1991 after 22 years working as a mine superintendent and foreman.

Controlling dust requires more workers and slows production. It takes time to hang plastic ventilation curtains that direct clean air to a mine’s working areas. The curtains are constantly knocked down by equipment, and miners leave them down because they reduce visibility. Water lines and sprays that hold down dust often clog.

Hundreds of miners said they scramble to put up curtains, fix water sprays and perform other required dust-suppression tasks only when a supervisor calls from the surface to warn them that a federal inspector has shown up.

How Mines Cheat

Underground coal-mine managers are required to test the air for five consecutive days or shifts every two months. They do this by pinning a pump about the size of a brick on the belts of miners who work in the most dust. A tube attached to a miner’s collar snakes down to the pump — weighing one to two pounds — which draws dust through a filter inside a plastic cassette. A government laboratory weighs the cassette to determine the amount of dust in the mine’s air.

Miners are supposed to keep the pump running for eight hours while they do their normal work. Most miners interviewed say they don’t.

“I’m not going to lie to you,” said George Bevins, 49, of Jenkins, Ky., who left the mines in 1992. “Most of the time, we just turn them off.”

Often miners take off the pumps and hang them where the air is clear of dust, they said. That can be an intake passageway, where fresh air is blown in from the surface, or the power center, where much of the mine’s equipment gets electrical power and where most miners leave their lunch pails.

“I’ve seen the men put them in their dinner buckets, and I’ve seen the superintendent put them at the power center where there is no dust,” said Lenville Bates Jr., a 24-year-old miner from Thornton, Ky. He said he has worked for three coal companies in the past year.

Many miners said they never get a chance to test the air because their bosses don’t distribute the pumps. Instead, they said, tests are run in the intake air or outside of the mine — or not at all.

Many mines hire a contractor to supply dust-testing equipment. “The operator would have some contractor drop them off after we went underground,” said Earl Shackleford, 37, of Wallins Creek, Ky., who was a foreman until he was injured in 1993. “We would never know they was there until quitting time.”

Connie Prater McKinney, who runs a contracting company based in Floyd County, Ky., was convicted in 1995 along with a co-worker of doctoring dust tests for five mines. They put the samples in coffee cans filled with coal dust, shook the cans and pulled out the samples when they had the right amount of dust.

McKinney refused a request for an interview, saying she has put the conviction behind her. She still works as a dust-sampling contractor.

Some miners agree to cheat because of a simple threat: “If you turn them on, you are fired,” said Crawford Amburgey, a miner for 30 years who retired in 1993 and lives in Letcher County, Ky. “I was told that many times.”

But most miners interviewed said their foremen never threaten them directly. Instead, the mine superintendent or safety director weighs every sample. If a sample looks as though it might have too much dust, many superintendents void it and make the miner who took the test wear the dust pump every day until he gets a test that will pass.

Troy Weaver of Coldiron, Ky., remembered the only time he actually wore a dust sampler correctly. “I got a bad sample, and they told me in front of everybody that I would be carrying that thing for the rest of my life if I didn’t get a good sample,” said Weaver, who worked underground for 18 years until 1991. “So I took it in there the next day and set it at the breaker box (in clean air) and got them a good sample.”

Choking Dust Levels

The result of all this cheating, say miners, is choking levels of dust. Billy Ray Stidham of Slemp, Ky., who left the mines in 1993 after 20 years, said, “You’d get dust balls in the comer of your eyes. Your throat gets dry and scratchy and full of grit. You’d vomit because it made you sick. You’d get dizzy because you can’t get enough air. You’d start aching between your shoulder blades because you’d cough so much.”

Dozens of miners described dust so thick they couldn’t see their feet or the head lamps of other miners. Those who are still working spit up coal dust every morning. Watzman, of the National Mining Association, said claims that mines are routinely dusty are “hearsay.”

“I’ve heard these accusations in the past,” Watzman said. “If those conditions exist, MSHA inspects them and, if there are exceedences (in dust levels), they write citations.”

Indeed, MSHA cited 32 percent of the nation’s underground mines in the 1996 fiscal year for excessive dust and related violations — even with all the problems with dust sampling.

Dusty conditions have been routine for so long that many miners see nothing wrong with them. Buddy Lilly, 53, of Cool Ridge, W. Va., said the dust where he worked was not all that bad.

Lilly’s wife told a different story. “His face was black when he’d come home,” Brenda Lilly said. “You could see his eyeballs, and that’s about it.”

Last year, after experiencing shortness of breath, Buddy Lilly got a chest X-ray. He had worked in the mines for only 19 years, and he had never smoked. But the film revealed that he had an advanced form of black lung. It usually kills quickly.

“It was quite a shock,” said Lilly.

Tags

Gardner Harris

The Courier-Journal (1999)