This article first appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 27 No. 3, "Digging for the Truth." Find more from that issue here.

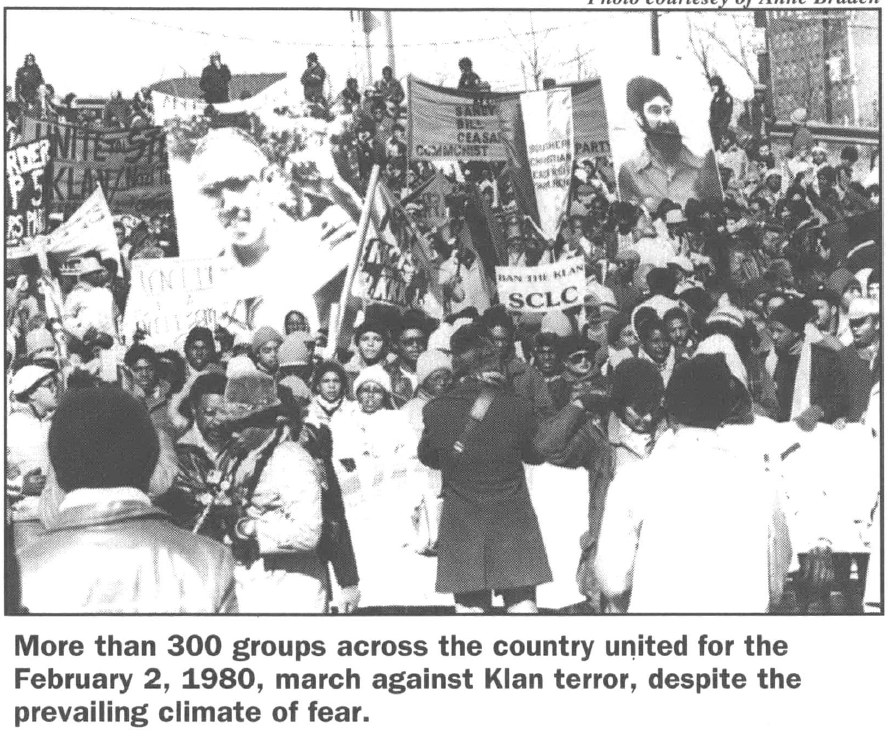

The massacre of anti-Klan demonstrators on the streets of Greensboro, North Carolina, by Klansmen and Nazis on November 3, 1979, and the protest march that brought 10,000 people there on February 2, 1980, produced a major turning point in this nation’s struggle against racism. These events created a new unity among people’s movements and touched off a decade of activism at a critical moment.

This side of the Greensboro story — the renewal of a vital, anti-racist movement in this country — will probably receive scant attention in mainstream accounts as we come to the 20th anniversary of the 1979 murders. But the story of how that movement was built is especially important today, as the nation faces a new wave of racist violence.

The February, 1980, march responding to the Klan attacks was one of the most broad-based and diverse anti-racist actions ever mobilized in this country, and a symbol of changing times among social change activists. About 60 percent of the marchers were African-American, just under 40 percent white. They came from the entire Eastern Seaboard, the South, and the West, and represented countless civil rights groups, religious institutions, unions, students and many left political groups. Many of the more than 300 national endorsing organizations had constituencies in the thousands, and despite a curtain of fear that enveloped the city, an estimated 2,000 of the marchers were Greensboro citizens.

The historic rally was organized in the face of huge obstacles. Within hours after the November 3rd massacre, the city and state developed a position saying the tragedy was in fact a “shootout,” a confrontation between two equally reprehensible groups, the racists and the Communist Workers Party (CWP), which had called the fall demonstration.

Despite the fact that TV footage showed Klansmen and Nazis shooting point-blank at unarmed demonstrators, this official version was picked up by the mass media in Greensboro and elsewhere; they never challenged it then or later. The November 3 survivors were depicted as villains, glad to sacrifice their loved ones to get martyrs for their cause.

In such a climate, the February march organizers had to fight the city for a permit and file court action to get use of the Greensboro coliseum. Agents of the FBI, the State Bureau of Investigation (SBI), and the Community Relations Service of the U.S. Justice Department visited campuses, churches, and individuals to tell them that there would probably be violence. Government pressure caused buses to cancel. The governor called out the National Guard, and the city declared a state of emergency. (On February 2, the marchers walked four miles in sub-freezing temperature in a spirited but peaceful fashion; the Klan did not appear.)

In a statement issued after the February 2 march, the coalition that had organized it said: “We believe we have tapped the sentiments of a new majority in this country — people who are alarmed at the new rise of racism in our land and who are willing to transcend the differences in theology, ideology, and philosophy that have previously divided them — and to act in unison in new crusades for justice in the coming years.”

The Greensboro massacre came at a time when social-justice activists in the South and the nation were splintered. After the movements of the 1960s were debilitated by government repression at the end of the decade, many young people — both people of color and white — turned to self-styled revolutionary organizations. Left-wing parties and politics proliferated; rivalry and sometimes hatred between them were intense. Most of them had thinly-concealed contempt for forces that had been movement allies in the 60s, such as groups based in the religious community. In turn, faith-based organizations were frightened of the radical groups.

I witnessed this period of splintering first-hand when an organization I had spent 17 years in, the Southern Conference Education Fund (SCEF), was destroyed by infighting in six months (I now suspect the government was involved). But I recall sitting at one of those contentious SCEF meetings with a friend, and saying, “You know, all these people will be back working together someday — because if you live and work in the South, whether you’re black, white or green, you know down deep that the main issue in this country is racism.”

Looking back, I think 1980 proved me right.

I first learned about the Greensboro massacre on Saturday night, November 3, when Rev. Ben Chavis called me from prison in North Carolina. Chavis was known as one of the “Wilmington 10,” who were serving long prison sentences on charges many thought were trumped up, accusing them of burning a grocery during protests against racism in the schools and violent attacks by Klansmen in Wilmington, N.C., in 1971. Chavis was the first African-American leader in the state to speak out in support of the victims and survivors of the Greensboro massacre.

The CWP scheduled a funeral march for Sunday, November 11. I did not know any of the CWP people, but I was a product of the civil-rights movement, where it was understood that “when someone is killed, you go.” I left a conference in Nashville Saturday night to drive over the mountains in the blinding rain. It was pouring rain in Greensboro, too, but almost 1000 people came out for the march, despite an intense campaign by public officials urging people to stay away. As we marched through the streets, the National Guard lined each side — with guns pointed at us.

When I returned to my home in Louisville, there was a message from an ex-SCEF colleague who had not spoken to me for three years. I returned the call, which came from Greensboro. The first words I heard were: “Well, what do you think?”

“What do I think about what?” I replied.

“What we should do about Greensboro,” came the answer. And that’s what we talked about. We worked together for a year, as did many others who had been estranged from each other. One day we finally decided to talk about the SCEF split, but the conversation was short — it didn’t seem important anymore.

While social-justice forces had been devouring themselves with internecine warfare in the 70s, the Klan had been organizing. Many of us had thought the Klan had been destroyed by the momentum of the 60s and some criminal prosecutions. But we became aware that it was far from dead — it was growing.

We sent observers to the Klan’s rallies and learned they had a new line. They weren’t against black people, Klansmen said, they were for white people. Blacks were now getting everything, and it was whites who were discriminated against — and the Klan would fight for their rights. It was the first time we heard the concept of “reverse discrimination.”

Despite their warmed-over image and sometimes-peaceful rhetoric, the new Klan was very violent. In May 1979, during a demonstration led by the Southern Christian Leadership Conference in Decatur, Alabama, Klansmen shot at Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) president Dr. Joseph Lowery and his wife Evelyn, and wounded three demonstrators.

The episodes of violence multiplied. North Carolina was a hotbed; several Klan factions were based there, and in September 1979, Klansmen joined with Nazis to form the United Racist Front.

The organized response started after the Alabama shooting. SCLC mobilized a march two weeks later that brought 3,000 people to Decatur. Walking along a road that day, Rev. C.T. Vivian, then on SCLC staff, and Marilyn Clement, director of the Center for Constitutional Rights (CCR), decided there must be a new coalition to mount a counter-offensive.

Bridge-building between erstwhile hostile groups began when Vivian organized a conference of people in Norfolk, Virginia, from diverse groups. The National Anti-Klan Network was born, adopting a four-point program: direct action, political action, legal action, and outreach to youth.

The barriers really fell, however, in December of 1979. The Rev. Lucius Walker of the Interreligious Foundation for Community Organization (IFCO), with SCLC’s support, issued a call for a conference in Atlanta that December to organize an offensive against not only the Klan, but what we called “the Klan mentality” in high and respectable circles.

The events of November 3 provided an unprecedented sense of urgency. People from 100 organizations descended on Atlanta, including Greensboro survivors. Movement activists who had not spoken for years planned together in workshops. Leftists no longer looked down their noses at the religious people, and the church people were not keeping the leftists at arm length. We called it “the spirit of Atlanta.”

It was here that the call was made for all people concerned about the rise of the right to come to Greensboro on February 2 — the closest Saturday to the 20th anniversary of the civil rights lunch-counter sit-ins that began there in 1960. The call said we should reclaim that other Greensboro heritage which activated the 60s for justice.

Bolstered by the power of the February 2 march, the National Anti-Klan Network dug in to build a nationwide movement. It had no money, but it set up an office in Atlanta and soon was working with victims of racist violence across the country, helping communities organize, taking delegations of victims to lobby in Washington, pounding on Justice Department doors demanding action. It also got the National Education Association to develop a curriculum on the history of racism in America.

In North Carolina, where officials were still calling violent Klan incidents “isolated pranks,” Rev. Wilson Lee of Statesville documented a statewide pattern after a cross was burned on his lawn. North Carolinians Against Racist and Religious Violence (NCARRV), led by Mab Segrest, built a broad campaign against the far-right onslaught, and by the 1990s, with legal help from the Southern Poverty Law Center, had pulled the fangs of the most virulent groups in that state. In the meantime, the Anti-Klan Network broadened its mission, became the Center for Democratic Renewal, and today is a center of organization against the continuing epidemic of hate crimes in the nation.

The weakness — some would say a fatal one — in the unity that developed in response to Greensboro was that its relationship to the victims was always tenuous. Many committed anti-racists did not want the CWP involved because they felt that their tactics, while not the cause of the November 3 killings, had made it easier for the Klan to attack. The CWP was removed from the February 2 march planning committee the week before the event.

The stated reason was that the CWP’s representatives refused to issue a public pledge not to bring guns to the march. CWP leaders said they refused because they, like all participating groups, had already pledged a non-violent march, no other group was asked for any further statement, and they felt an additional statement from them would give credibility to the government’s line that the communists themselves caused the massacre.

I never agreed with the majority stance against the CWP. Maybe this was because, in the 1950s, I had been demonized in Louisville and painted a villain in similar anti-communist hysteria.

One could legitimately disagree with the rhetoric of the CWP which had announced its demonstration as a “Death to the Klan” event. But none of the rhetoric changed the basic danger posed by the fact that the Klan and Nazis could kill unarmed demonstrators in a broad daylight in front of TV cameras. I felt, although this was not the intent of those who rejected the CWP, that excluding them from the planning committee gave the government another excuse for failing to bring the killers to justice.

Because the Greensboro survivors were vilified in the media, most of the public never knew much about those who died. The CWP always believed they were deliberately selected through collusion of the FBI with Klan and Nazis. At the trial of their civil suit, the survivors introduced an affidavit from a textile worker who swore that she was visited by FBI agents shortly before November 3 and asked to identify photos of two of those later killed. But this woman died before the trial, and the FBI denied her story, so the CWP was never able to prove their contention of collusion in court.

But if someone had indeed hand-picked who to shoot, they could not have done a better job. Those killed were obviously remarkable human beings.

All five had been activists for civil rights and against war in the 60s. Like many youth who lived through that era, they began looking for deeper answers and turned to Marxism. These five found their way to the Communist Workers Party which, like revolutionary groups before it, wanted to organize the working class, and its members got jobs in textile mills and hospitals.

The five victims were college educated. Many such people can’t relate to working people, but these activists seemed different. Jim Waller organized a successful strike in his textile mill and was elected local union president. He was a doctor and set up an informal free clinic in his home in the evenings. Bill Sampson, who had graduated from Harvard Divinity School, became a leader in another textile mill and was a shoo-in for election as union president when he was killed. Michael Nathan was a doctor who organized support for workers at Durham County General Hospital. These three were white.

Cesar Cauce was the son of anti-Castro Cuban refugees; he joined the 60s movement and in 1979 was working at Duke Medical Center and organizing workers. Sandi Smith was a respected African American leader, who had been president of the student body at Bennett College. She had just relocated to Kannapolis to work in Cannon Mills. Nelson Johnson, who was badly beaten but not killed on November 3, was a recognized youth leader in the African-American community in Greensboro in the 60s and became the CWP leader there in the 70s.

Feeling marginalized by the new anti-racist movement that was being built, the Greensboro survivors had to mount their own campaign to establish the accountability of those responsible for the murders, and eventually they did — creating one of the broadest support operations against repression this country has ever seen.

They did it by knocking on doors throughout the country and talking to people, one by one. (Marty Nathan, one of the widows, personally visited every member of the Congressional Black Caucus). Rev. Tyrone Pitts, then staffing the Racial Justice Working Group of the National Council of Churches, came to Greensboro and publicly announced support, opening the way for many religious bodies to follow suit.

Eventually, scores of organizations supported a Greensboro civil suit for damages, hard-working lawyers volunteered, and a huge mailing list was built. This mailing list provided the base for on-going fundraising by the Greensboro Justice Fund, now a people’s foundation that supports local organizing against racism, thus turning tragedy into a creative vehicle for the future.

Later in the 1980s, the CWP went out of existence, as did most of the 1970s revolutionary groups. Some Greensboro survivors today are very critical of some of their own methods in the ’70s — believing that, like most groups that considered themselves vanguards of the revolution, they were too rigid, too convinced that only they had “the truth,” and too given to rhetoric out of touch with the people they wanted to reach.

But virtually all the Greensboro survivors went on to lead activist lives. The four widows work steadily to make the Justice Fund more effective. Others work with unions or as community organizers. Nelson Johnson, who comes from a Baptist tradition, studied theology in Richmond for four years and came back to Greensboro in 1989 to found the Faith Community Church. He is again a recognized leader of that city’s movements for justice — for worker rights, educational equity, affordable housing, and support for African Americans and the poor who are filling the prisons.

The Greensboro survivors are convinced that the unfinished business of this chain of events is for citizens of Greensboro to recognize and come to terms with the truth about November 3 — perhaps most importantly, the overwhelming evidence of the government’s involvement in the massacre. In mid-1980, for example, a Greensboro Record reporter revealed that an agent of the Federal Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, & Firearms (BATF) was intimately involved. The Institute for Southern Studies documented the role played by the Greensboro police in its fall, 1980, report The Third of November, and in July of 1980, Pat Bryant reported in this magazine’s pages the efforts of the Justice Department to undermine protest. Even more evidence of FBI and BATF involvement came out in the civil trial (see time-line).

It is always a wrenching experience for people to believe that their own government can commit crimes, and even murder. But the Greensboro survivors believe this is the road to healing and reconciliation. They have hoped it would begin to happen as the city marks the 20th anniversary of the massacre.

As for those of us who helped organize the movement that came from the Greensboro events, we can hardly say we laid claim to the 1980s as our leaflet for the February 2nd march said we would. We certainly did not rid the nation of racism, or perhaps even begin to touch its deeper manifestations in our institutional structures.

But, in 1980 and in the decade that followed and on into the ’90s, we did prove that huge numbers of people across our nation can be mobilized to say “NO” to racism. Today, as almost every day brings news of racist violence — either by vigilantes or the police — we again need the unity and the commitment that fired the movements in the wake of November 3, 1979. To think what might have happened if we had let the Klan and Nazis go unchallenged in their brazen attack on the streets of Greensboro in November of 1979 is to contemplate the unthinkable.

The Greensboro Massacre Timeline

November 3, 1979:

Nine cars carrying 35 self-avowed Ku Klux Klansmen and Nazis drive to an African-American housing project, where an anti-Klan demonstration, called by the Communist Workers Party (CWP), is assembling peacefully. About 100 demonstrators are singing freedom songs; some have brought their children. In the broad daylight and in front of four TV cameras, the Klansmen and Nazis fire 39 gunshots. Four demonstration leaders are killed at the site — Cesar Cauce, Bill Sampson, Sandi Smith, and Jim Waller. A fifth, Michael Nathan, dies two days later. Ten other people are wounded, one critically. Six demonstrators are later arrested on felony riot charges. Fourteen of the 35 Klansmen and Nazis are subsequently arrested.

February 2, 1980:

A march organized by an unprecedented coalition of civil-rights groups and endorsed by more than 300 national organizations brings 10,000 people to the streets of Greensboro. Organizers say the purpose of the march is to “say NO to racism” and “lay claim to the 1980s.”

June-November, 1980:

Six Klansmen and Nazis are tried for murder in state court. Before the trial, the prosecutor tells the press: “I fought in Vietnam, and you know who my enemy there was.” The defendants plead self-defense. An all-white jury acquits them, despite viewing slow-motion videos that show the Klansmen and Nazis calmly taking guns from car trunks, loading them, and firing pointblank at unarmed demonstrators. The state never tries any other attackers; riot charges against the demonstrators are also dropped.

1980-1983:

Documentation emerges that agents and informants of the Greensboro police, the federal Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco & Firearms (BATF), and the FBI helped organize the November 3 attack, that their superiors may have been involved, and that they knew of the Klan/Nazi plans to fire on demonstrators. A police informant working inside the Klan led the Klan caravan to the demonstration site. Evidence also develops that the State Bureau of Investigation (SBI), Community Relations Service of the U.S. Justice Department, and FBI worked intensively to derail public protests against the killings. National pressure builds for federal prosecution of the killers.

January-April, 1984:

Nine Klansmen, including the police informant, are tried in Federal Court in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. The chief federal investigator is the same FBI agent who had investigated the CWP in the early fall of 1979. Again, an all-white jury acquits the Klansmen. The defendants again plead self-defense, and successfully argue that the civil rights law under which they were indicted requires proof of racial motivation, and that their motive was not racial but political: they were patriots who only wanted to confront communists.

February-June, 1985:

A large civil rights suit filed in 1980 by widows and survivors of the massacre comes to trial in Federal Court. A six-person jury (this time including one African American), rejects many victim claims, but finds seven Klansmen and Nazis, two Greensboro police officers, and the police informant liable for Michael Nathan’s death. His widow and daughter are awarded $350,000. The city of Greensboro, while refusing to admit complicity, pays the entire judgement — for Nazis and Klansmen as well as the police.

Michael Nathan’s widow, Marty, divides her share of the judgement with other plaintiffs, who each donate a portion to the Greensboro Justice Fund. Starting with this seed money, the Fund goes on to support dozens of groups working for racial, social justice — thus, 1979 survivors say, creating a living memorial to those who died.

Fall, 1999:

The Justice Fund, in cooperation with the Beloved Community Center — a faith-based coalition — prepares for a week of events marking the 20th anniversary of the massacre. They host “conversations” across the city, asking citizens to look at what really happened November 3, and stating that Greensboro can never move forward constructively until it comes to terms chapter of its past.

For more information about the events on November 3, 1979, there are several sources available. The Institute for Southern Studies report, “The Third of November,” was one of the first studies to detail the complicity of the FBI and law enforcement officers in the Greensboro killings. For copies, send $8 to the Institute for Southern Studies, P.O. Box 531, Durham, NC 27702, or call (919) 419-8311 x21. A pamphlet describing the history and legacy of Greensboro is available from the Greensboro Justice Fund, P.O. Box 4, Haydenville, MA 01039-0004, or by calling (413)268-3541.

Tags

Anne Braden

Anne Braden is a long-time activist and frequent contributor to Southern Exposure in Louisville, Kentucky. She was active in the anti-Klan movement before and after Greensboro as a member of the Southern Organizing Committee. Her 1958 book, The Wall Between — the runner-up for the National Book Award — was re-issued by the University of Tennessee Press this fall. (1999)