At 11, Littlest Shooter had a Life of Guns

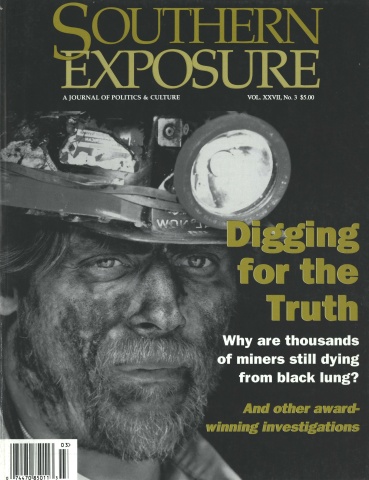

This article first appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 27 No. 3, "Digging for the Truth." Find more from that issue here.

In the midst of the recent wave of school shootings, but before the tragic killings in Littleton, Colorado, the Louisville Courier-Journal decided to explore possible answers through a massive project of “shoe-leather journalism.” Without preconceived ideas, without even a working title for the series, the Courier-Journal sent teams of reporters into the field in four towns — Paducah, Ky., Pearl, Miss., Jonesboro, Ark., and Springfield, Ore. — to seek out “the roots of school violence.”

In 28 articles by Jim Adams, James Malone, Rochelle Riley, and C. Ray Hall, the series covered a vast array of subjects, explanations, and solutions. The following excerpt covers one of the most important issues raised by the shootings, the problem of gun proliferation and control, but also addresses the stereotyping of Southern culture as “irresponsible” and “gun-happy.”

JONESBORO, Ark. — On his way to school, the small, skinny boy was struggling through the pines, oaks and sweet gums when he and his pal came to a fence in the woods. It was all he could do to climb it, so heavy was the load they were hauling: three rifles, seven handguns and at least 487 rounds of ammunition.

Two bullets for every child enrolled at Westside Middle School.

The wiry boy with the fragile looks, Andrew Golden, was merely 11 years old, and he seemed a full head shorter than his 13-year-old friend. But he’d played no small role in a burglary by crowbar that morning at the home of a sworn lawman for the Arkansas Game and Fish Commission — his own grandfather, Doug Golden. The boys had walked out with seven guns. Before that, they’d lifted three handguns from Andrew’s home while his parents were at their jobs as small-town postmasters.

Each boy — Drew, as he is called, and Mitchell Johnson — was known for a love of shooting. But with Golden, the passion for hunting, shooting and weaponry was a deep family tradition.

So after the boys had lugged the Golden family arsenal over the fence in the woods and opened fire upon Westside Middle School, the big issue for a lot of people was guns — an 11-year-old and his life with guns.

At the time, the boy’s grandfather thought he could shed light on things. Doug Golden began talking to the press about Drew — the boy who had just carried his surname and his carbine into an ignominious place in Arkansas history.

The family photo album was opened, and a nation was aghast:

Toddler Drew in full grin, circa 1990, dressed in camouflage and hugging what appeared to be a firearm.

Clean-cut Drew, circa 1992, in a two-handed firing position, aiming what appeared to be a pistol.

Young Drew, dressed in cowboy garb, holding what appeared to be a shotgun that was almost as long as he was tall.

A myopic Doug Golden had controlled the facts, but not the spin. He’d wanted the world to see the child inside the shooter: the trumpet player, the boy who knew and respected the power of weapons. To see that guns weren’t the issue.

But, even if the guns in the photos weren’t real — at least one was a studio prop — much of the outside world still saw a gun-happy child being raised in an irresponsible Southern culture. Now the culture had a poster boy.

“Armed & Dangerous,” declared the cover of Time magazine, showing a tiny, camo-clad Arkansan, Drew. Doug Golden may now wish he’d never opened his mouth.

One recent autumn afternoon, a great cloud of yellow dust trailed Doug Golden’s official green pickup truck along the gravel road as he arrived at the headquarters of a state wildlife management area he oversees near this northeast Arkansas Town. Waiting for him were a couple of visitors from a newspaper in Kentucky, wanting to talk about his grandson.

“Let me get out of this truck so I can whoop both of you,” Golden said, leaving his sidearm on the console and his shotgun propped against the passenger’s seat. Then a broad smile crossed his face. A leathery, barrel-chested man inside a khaki uniform, Golden lit a cigarette, buried it deep between two beefy fingers, and listened to a reporter’s plea. Finally, he said his lawyer advised him not to discuss Drew anymore.

The following evening, supper was interrupted by a knock on the door of Drew’s parents, the only home Drew had ever known, a one-story, ranch-style house with a stone facade. Nothing on the exterior says it’s also the registered office of a local pistol-shooters’ club.

At the front door, the man who had taught his boy how to shoot listened to yet another request to talk about Drew and his life here. One hand on the door, Dennis Golden stood patiently, chewing a bite of his meal, while behind him the house was still, except for the noiseless movements of a woman seated at a table. It’s an empty nest, now that Drew is gone.

“I ain’t got anything to say,” Dennis Golden finally said.

Twyla Clevenger has fond recollections of her years living next door to Dennis Golden, who is now 41 years old, and Patricia Golden, now 45. “Real nice people,” Clevenger said. “They had a very typical family life.”

Clevenger watched as both Goldens filled weekends with garage sales, yard work and Sunday dinners. Dennis sometimes rode Drew on an off-road vehicle up and down Royale Drive — a ramrod-straight dead end with one Baptist church and 21 small and medium-sized houses, the kind of place teachers and police officers call home.

Clevenger said that after she and her husband separated, Dennis Golden helped her son, Josh, with the nuances of lawn mower repair and go-cart maintenance. Dennis also at times set up a bale of hay in his back yard and taught Clevenger’s two older children how to shoot a bow and arrow.

Clevenger said Pat Golden had two children from a previous marriage, but Andrew was the only child she and Dennis have had in 16 years of marriage. Drew, now 12, and Clevenger’s daughter, Jamie, “basically grew up together,” until Twyla Clevenger and her children moved away in 1995.

Jamie’s older brother and sister “would eat dinner at the Goldens’ a lot,” Twyla Clevenger said. “When I found out Dennis had guns, that was a big issue with me.” But she said her worry eased when she learned that “he was very strict with those guns” and kept them locked up.

Twyla and Jamie Clevenger both recall problems with Drew, although nothing anyone saw as omens of major crime.

Drew sometimes cursed. “I know Pat hated it,” Twyla Clevenger said. Drew also was once asked to leave a day-care center because of misbehavior — vulgar language and fighting, as Clevenger understood what Pat Golden told her. “She was embarrassed about it,” Clevenger said.

And there was the thing about Fluffy.

Jamie said that when she was about 7, she found her favorite cat lying in a trash can and picked him up, not realizing Fluffy was dead. “Drew told me he shot the cat with a pellet gun,” Jamie Clevenger said.

Two other children came running when they heard Jamie scream: neighbor Jenna Brooks and her visiting cousin, Brynn Brooks. Jenna Brooks, some six years later, would be shot through the thigh in the Westside assault, and Brynn Brooks’ younger sister, Natalie, would be killed.

Whether Drew really killed Fluffy with a pellet gun isn’t an established fact. Jamie said she saw no blood, and there were no witnesses.

But not long before, Twyla Clevenger said, she did watch Drew push kittens belonging to the Clevengers head-first into the diamond-shaped openings of a chain-link fence, then tap them with the heel of his hand to pop them through. Clevenger said they weren’t hurt.

Since the shootings, several people in the neighborhood have described Drew as quite typical. “Drew’s just like all the other little boys I’ve ever had,” said neighbor Judy Crowell, a first-grade teacher at Westside Elementary.

But Twyla Clevenger came to view Drew as “a little more uncontrollable. . . . Drew’s not just high-activity. It was more mischievous.”

And another neighbor, Debbie Wisdom, came to view him as flatly sinister. Wisdom’s home is a gathering spot for children, but “I’d tell my two (children), ‘You’re not to play with Drew, I don’t want him in my yard,”‘ she said.

“There was something about Drew’s eyes I didn’t trust. I’m telling you, there was evil in his eyes.” On two or three occasions, when he was very young — 5, she guessed — Drew made obscene gestures to her when she drove past, Wisdom said.

For years, she said, it seemed that Drew’s parents would not allow him to leave their yard without them. The Goldens “are sweet people,” Wisdom said. “But they don’t need to deny that their child has a problem.”

Other episodes, innocent enough in isolation, have taken on almost legendary proportions around town:

Drew sometimes wore a sheathed hunting knife around Royale Drive. In the first grade, Drew was paddled after shooting a sand-and-pea-gravel mix into a girl’s face with a popgun. On another occasion, for a school project, he invented a script for a “Quick Draw McGraw” puppet show that ended with a gun battle.

Jonesboro debates whether all that means Drew was obsessed with guns or not, but clearly he was around them. The Golden home is registered with the state of Arkansas as the office of the Jonesboro Practical Pistol Shooters Association, and Dennis Golden became its registered agent when it incorporated in 1995. It’s affiliated with a national group, the U.S. Pistol Shooters Association, and today meets many weekends in an old gravel pit in nearby Bono, Ark. Shooters are timed as they fire from behind obstacles at cardboard or metal targets, which may be rigged to move, bob or swing.

While they seem to come and go with their heads down a lot these days, Patricia and Dennis Golden did reflect publicly on their son once, through their lawyer’s pleading in a lawsuit filed against them: “Despite their (the Goldens’) best efforts, something went terribly wrong in the mind of Andrew Golden to cause the infliction of such tragedy and horror.”

In other words: Andrew’s mind is the issue. Not guns.

The day of the Westside shooting, the two boys tried and failed to get into Dennis Golden’s combination-lock gun safe, which held his long guns and at least one gun belonging to Drew. A family friend said the fact Drew didn’t know the combination is evidence of Dennis Golden’s prudence.

Another person familiar with the day’s events said that after the boys broke into the home of Doug Golden, they found a rack of rifles with a padlocked steel cable threaded through the guns’ trigger guards. But, this person said, Drew knew the key to the lock could be found above the rack.

In boyish hands, then, were the rifles that would kill five and wound 10.

Arkansas Shooting: THE FACTS

When: Tuesday, March 24, 1998, about 12:30 p.m. It was the second day of classes after spring break.

Where: Jonesboro, Ark., at the Westside Middle School, in the center of the 75-acre Westside school district complex about four miles west of the city limits. The campus is in a distinctly rural setting. The curving road along the front of the campus is paved, but dusty, gravel county roads run behind the campus, and fields of soybeans and rice dominate the landscape. The terrain is flat. The schools are brick and modern in design.

What happened: Andrew Golden, an 11-year-old sixth-grader, and Mitchell Johnson, a 13-year-old seventh-grader, hauled 10 guns and a large amount of ammunition to within 100 yards of the middle-school building. Golden entered the middle school, pulled a fire alarm and then ran from the school to rejoin Johnson on a sloping, wooded piece of ground. After many of the students responded to the alarm and filed out of the school, the boys opened fire. Police think the boys fired at least 22 times, because that’s how many spent casings were found.

The toll: Five dead, all female; four of them students and one a teacher. Ten others — nine students, one teacher, nine female — were wounded.

The case: At a final “adjudication” hearing Aug. 11,1998, Mitchell pleaded guilty to delinquency and tearfully expressed remorse. Andrew, silent and dispassionate, was declared delinquent by the judge, a ruling his attorney has appealed. Both boys are to be confined until age 18, and possibly 21. — Jim Adams

Tags

Jim Adams

The Courier-Journal (Louisville, Ky.) (1999)