Whiting Out History

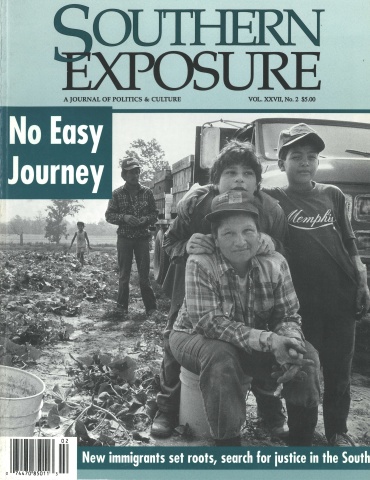

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 27 No. 2, "No Easy Journey." Find more from that issue here.

The immigration debate in America is most centrally an argument about the order of things, about where people fit, about who belongs and who does not. The vast majority of Americans have been immigrants, whether voluntary or otherwise, coming from somewhere else in times recent enough to be remembered and chronicled. But from the nation’s start, many Americans have also often been anti-immigrant.

In the country’s first naturalization law in 1790, Congress attempted to legislate the definition of “American.” Creating for the first time a national definition of citizenship, this law permitted people to become citizens who had resided in the new nation for two years and would swear allegiance to the Constitution. But the act added a crucial third qualification — only “free white persons” could become naturalized U.S. Americans. Being a citizen of the nation was racialized from the start.

Benjamin Franklin, in his Autobiography, railed against German immigrants’ disdain for assimilation and unwillingness to give up their language. By the 1850s, America’s hatred of more recent arrivals spread to the West coast. Miners, who had only recently arrived in California themselves, turned on newer immigrants from China, harassing them with special taxes. The miners also violently forced the Chinese immigrants off land that was supposed to be available to anyone who claimed it first. In the East, the first Nativist Movement of whites organized widespread hatred of Irish immigrants into a political party-one that completely dominated Massachusetts state politics by the middle of the decade.

For most immigrant communities, an important part of the process of becoming American, it seems, has been demanding the exclusion of some more recently-arrived group. But Americans have also been people, however long in residence, who could lay claim to “whiteness.” This standard excluded many — the slaves and then ex-slaves in the South, the Chinese and Indians and Latinos in the West, European immigrants in the Northeast, and now Latinos in the South. Ironically, these excluded groups that provided an “other” against which whites could claim a higher status also served as the cheap labor that helped white “Americans” to a higher standard of living.

Belonging to this country, in terms of both civil rights and cultural identity, has depended more on “color” than place of birth. Until the Civil War, national citizenship, with its explicitly racial qualifications, remained more a symbolic concept than a reality. The war, of course, destroyed the national community that had been imagined in the late eighteenth century. The war also made an earlier racialized conception of American identity entirely unworkable. Emancipation gave the nation four million “new” residents who were not, under any understanding of the term, immigrants. The Fourteenth Amendment, ratified in 1868, made the citizenship rights of the freed people explicitly clear and demanded that the federal government protect the rights of African Americans.

From Appomattox through the end of the century, Americans struggled to imagine a new national community in the midst of a rapid economic and social change as immigrants entered the country in greater numbers and from a wider variety of places. And with this change, there was a growing tendency to define social issues through the lens of race.

After the Fifteenth Amendment failed to grant the vote to women, for example, Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton broke with their former allies like Frederick Douglass to oppose its 1870 ratification. In their paper, The Revolution, they pioneered the kind of racist arguments for women’s (understood as white) suffrage that would become commonplace in the late nineteenth century. Why let an illiterate ex-slave or an ignorant Irishman vote over an educated, American born white woman? Race, not gender, they implied, marked the limits of American belonging.

The 1880s and 1890s, then, were decades of intense reaction to these post-Civil War movements that promoted a more racially inclusive definition of American citizenship. White Western settlers made themselves Americans by segregating Native Americans and attempting, through a series of acts beginning with the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, to halt entirely what they saw as a rising tide of “yellow” immigration. The second white Nativist movement permeated Northeastern society, spawning both an organized political effort to limit or halt immigration altogether and a revival of English architecture, domestic furnishings, and heritage.

In 1896, the Supreme Court “separate but equal” decision in Plessy v. Ferguson made explicit just which people were equally created and which were not. By 1898, Confederate and Union veterans were shaking hands at battlefield reunions as their sons and grandsons marched side by side up San Juan Hill in the Spanish American War. Neither the ex-slaves nor the Filipinos “liberated” in the Spanish American War, it seemed, would really be citizens.

By 1915, Washington D.C., from federal employment to public facilities, was completely segregated and D. W. Griffith’s film Birth of a Nation played to packed audiences from Woodrow Wilson’s White House to California. The spectacle of film gave American whiteness a new mythic power. Birth portrayed the modern American nation’s genesis in the reunion of Northern and Southern whites in a violent attack on and exclusion of African Americans.

Finally, white women received the vote in 1920 that African American men and women in the South were still being denied. The 1924 National Origins Act completed this cycle of the racialization of American citizenship by instituting quotas to reduce southern and eastern European immigration and by excluding Asians entirely.

Like the Civil War, the social movements of the 1960s destroyed this second racialized conception of American identity and community, overturning both Southern segregation and national immigration quotas. At the end of another century, it is worth asking once again: What route will we take? What sort nation do we want be? Will the most powerful conception of American belonging continue to proclaim a superficial universalism by hiding the whiteness at its core? Will our twenty-first century nation welcome immigrants whose skin color, way of speaking, or culture marks them as non-white? Or will we — all of us — finally imagine a national community that economically, politically, socially, and culturally includes us all?

Tags

Grace Elizabeth Hale

Grace Elizabeth Hale is Assistant Professor of American History at the University of Virginia and author of Making Whiteness: The Culture of Segregation in the South, 1890-1940. (1999)