This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 27 No. 2, "No Easy Journey." Find more from that issue here.

They broke the mold after they made Virginia Durr, who died this past February at the age of 95. Her life spanned most of the 20th Century and almost seven decades of the struggle for a democratic South.

Virginia grew up in Birmingham but spent summers on the family plantation in the Alabama Black Belt, where her family was part of the Old South ruling class. She was born into a white society that said the only role for a woman was to be attractive to men, become the belle of the ball, and “marry well.”

But she was part of that generation that got its political education from the Great Depression. Virginia’s began when, as a young Junior Leaguer in Birmingham, she saw starving children devastated by rickets. When she was 30, she moved to Washington where her husband Cliff, a brilliant young lawyer, took a job in Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal government. Her real awakening came when she attended hearings of the Congressional La Follette Committee, which was investigating the beating and killing of union organizers in the South. There she realized it was nice Christian men she knew, industrial barons of Birmingham, who planned these atrocities. She was horrified.

She became an ardent New Dealer, union supporter, and a founding member of the Southern Conference for Human Welfare, formed in 1938 to bring African American and white Southerners together to work for an equitable South. Virginia’s great passion was the right to vote, and she became a leader of the movement to abolish the poll tax, one of the devices used to deny the ballot to African Americans — and also to poor whites and women. The house where Virginia and Cliff raised their four daughters in Alexandria, Virginia, became a gathering spot for the crusaders of that period, many of them high government officials.

When the domestic Cold War hit in the late 1940s, terror gripped Washington, as every crevice was said to contain a Communist. Organizations Virginia belonged to were destroyed by purges, her friends were called before investigating committees and lost their jobs. Many people were running for cover like rats. Both she and Cliff were appalled. By then he was chair of the Federal Communications Commission and resigned rather than enforce President Truman’s Loyalty Oath. Virginia had many Communist friends. She said later no one ever really asked her to join the party because they thought she talked too much.

She and Cliff went back to Alabama, and in 1954 she was subpoenaed by Sen. James Eastland of Mississippi who was “investigating” people working against segregation. She went to New Orleans and powdered her nose as Eastland roared questions. All she would say was, “I stand mute.” Her friends laughed about that for years; it was the only time in her life that Virginia stood mute.

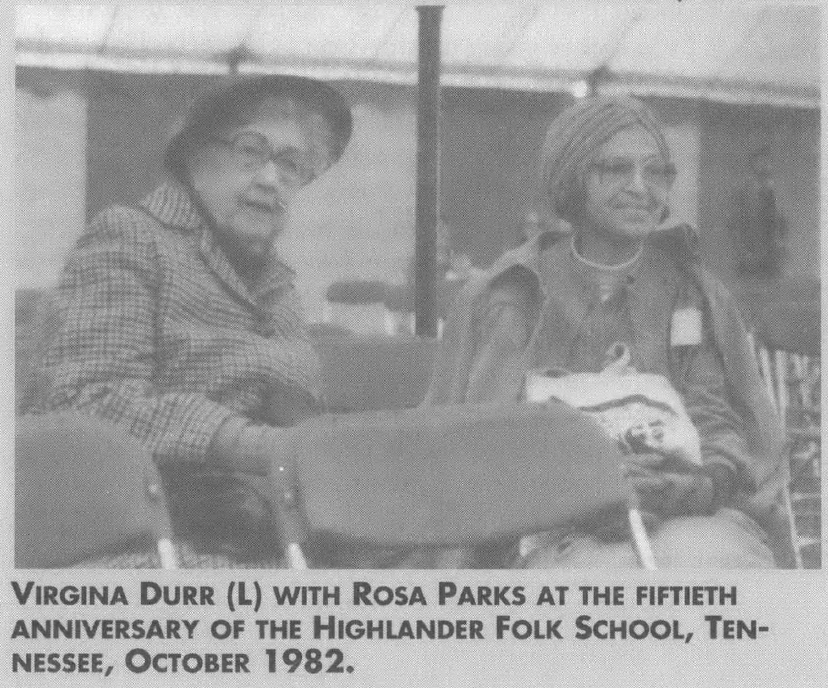

That same year, the Supreme Court handed down its landmark decision outlawing school segregation. The Durrs were among the few whites in Alabama who supported the decision. They had also become friends with Rosa Parks and other African-American activists; when Ms. Parks refused to move on the bus in 1955, they supported the boycott, and Cliff helped on the legal challenge. The Durrs became outcasts among whites in Cliff’s hometown. But as the civil rights movement heated up, their small apartment became a mecca for activists from across the South and the nation. When Cliff retired, they moved to Pea Level, a family farmhouse in nearby Elmore County, and the multitudes came there. Cliff died in 1975, and for 20 years — until ill health finally overtook her — Virginia continued to be active, and historians beat a path to her door.

Virginia someway escaped the Southern custom of phony politeness. She asked everyone the most impertinent questions about their personal affairs and later passed on these stories — not as gossip, but because she had a voracious interest in people. In later years, when people came to me with tape recorders and said, “Tell me about the ’30s,” I sent them to Virginia. Not only did she know everything that happened then, I said, but she knew who slept with whom every night of the ’30s. “That’s important,” she would say, at which point she would launch into a story, for example, of a union organizer who found out too late that the woman he had been sleeping with was a company agent.

Like many white Southerners who broke with tradition, Virginia continued to like people whose politics and racial views she considered atrocious. Her unadulterated fury was reserved for the Cold War liberals who became what she called “red-baiters.” When one leading liberal who helped break up the movement against the poll tax did something equally reprehensible almost two decades later, she said: “He’s still a bastard, and he hasn’t learned a thing in 20 years.”

I met Virginia in 1955, just after the Montgomery bus protest started. My husband and I had been charged with conspiring to overthrow the government in Kentucky after we bought a house for an African-American couple in a segregated neighborhood. I had grown up in Alabama, and although my family was never part of the ruling class, like Virginia I had grown up in those circles. We became fast friends.

But I was 21 years younger, and our life experiences were very different. She had moved in the power circles of Washington for almost 20 years, where if she wanted to organize a little committee meeting, she just “called up Eleanor and went to the White House.” From that, she had to adjust to the life of an outcast in Alabama. Since I became active as the Cold War was escalating, I never expected to be accepted in the status quo. I told Virginia 1 thought those years were much harder on her than on me.

Our experiences in black/white relations were also very different. Virginia’s generation challenged segregation in the 1930s when Old South traditions still prevailed and even civil rights organizations that were interracial tended to be white-dominated. By the time I became active, African Americans were already asserting independent in no uncertain terms. Virginia could never accept what she saw as “black separatism.” In the 1960s, she could not come to terms with the Black Power Movement, whereas I thought it was a major creative leap forward for the country.

But I always listened when Virginia, from her roots in the ’30s, reminded activists that a major problem was inequitable distribution of wealth and “huge corporations that own the government.” “That’s what you’ve got to oppose,” she would say. “We need a new economic system.”

Virginia and others of her generation challenged the entrenched South when it was a literal police state, and dared to envision its transformation. I have often wondered whether, if I had been born 20 years earlier, I would have had the vision or the courage to do that. Everyone who came later stands in debt to Virginia and her contemporaries.

Tags

Anne Braden

Anne Braden is a long-time activist and frequent contributor to Southern Exposure in Louisville, Kentucky. She was active in the anti-Klan movement before and after Greensboro as a member of the Southern Organizing Committee. Her 1958 book, The Wall Between — the runner-up for the National Book Award — was re-issued by the University of Tennessee Press this fall. (1999)